In 1931, Samuel Goldwyn offered Coco Chanel a guaranteed $1 million to come to MGM and design wardrobes for his films. Reluctant at first, she eventually agreed. For her first film, a Busby Berkeley musical titled Palmy Days, Gilbert Adrian was her assistant.

Adrian was not yet the costume-design legend he was to become, but he certainly knew his way around the wardrobe department. And he tried to advise the French couturier that her fashion’s characteristic subtlety wouldn’t work for film costumes.

Above all, he explained, these pieces needed to photograph well and complement the actress, not necessarily the cut of the cloth. Such compromises did not suit Chanel. As a result, her costumes never excited audiences. The designer “made a lady look like a lady,” wrote The New Yorker, but “Hollywood wants a lady to look like two ladies.”

After three films, she called it quits.

The work has not gotten easier since those early days. In addition to accommodating the actors, costume designers must take into account the mise-en-scène. “As soon as we have a sense of what the room or location will look like, we’ll show the costume designer,” says Andrew Baseman, set decorator for Crazy Rich Asians. “But it’s not until the day of the shoot that everything comes together.”

As a result, multiple options must be prepared for each actor in every scene. After all, Baseman points out, “you’re not going to change the room, but you can change the dress.”

Of course, when it all comes together, the result can be magic. Set decorators like Baseman are part of “a small community of people that make a huge impact on design,” says Jake Baer, CEO of Newel, which often rents its furniture to movie and television productions. “I love seeing how they work. They build these incredible sets, and then once they shoot the film, it’s all gone. But in a way they live forever on the big screen.”

So, what makes a fashion film? “There is a level of desire that gets attached to a character, lifestyle or an item,” says Patrick Michael Hughes, an assistant professor at Parsons School of Design. “It takes an iconic outfit or an accessory that everybody wants.” Brent Amerman, proprietor of an eponymous San Diego–based boutique, puts it this way: “It’s like you have a bunch of daisies and a single rose. One piece is the centerpiece. The daisies are pretty nice, but that rose is beautiful.”

Here, we look at a few of our favorite films and explore what makes them so fashionable.

Crazy Rich Asians

In a world of haute luxury, it’s a battle of old money versus new, and combat is waged with dazzling homes and wardrobes that make fashion-conscious hearts flutter. This is the stage on which John Chu’s 2018 Crazy Rich Asians plays out. Based on Kevin Kwan’s satirical novel and starring Hollywood’s first all-Asian cast in 25 years (the last was 1993’s Joy Luck Club), it tells the tale of New York economics professor Rachel Chu (played by Constance Wu) who discovers that her handsome Singaporean boyfriend, Nick Young (played by Henry Golding), is filthy rich.

“Fifty years from now, Crazy Rich Asians will stand out as our period’s version of Dinner at Eight, a 1930s rom-com starring Jean Harlow,” says Hughes. “Everybody’s so dressed up, and to our modern eye, it looks crazy, kooky and fun.”

But this crazy, kooky style — perhaps best embodied by Rachel’s college friend Goh Peik Lin (played by Awkwafina) — speaks volumes. “The easiest way to communicate [the wealth of] the Goh and Young families,” costume designer Mary Vogt explained to the Los Angeles Times, “was to think about what designers they would wear and how they would dress. The Young family would never wear Versace, but the Goh family was dripping in Versace.”

And then there’s Rachel, who arrives in Singapore, this unfamiliar land of glamour, in a no-name, sensible shift. Her Cinderella makeover takes place in Peik Lin’s private dressing room. Says Baseman, “The key [to this scene] was to have as many colorful, outrageous costumes as we could.”

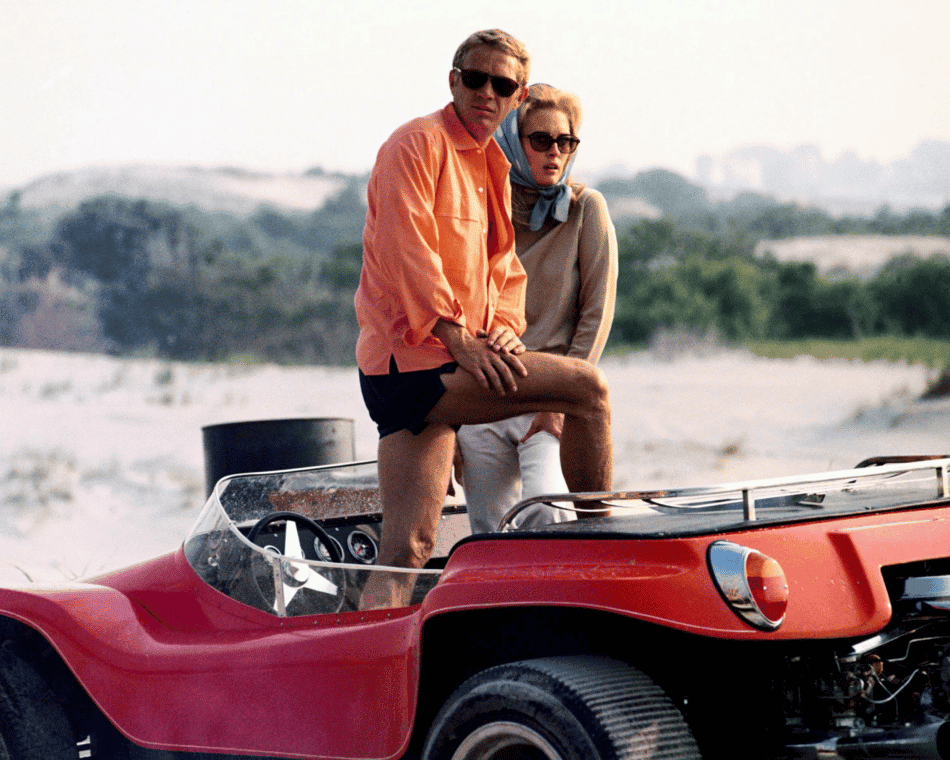

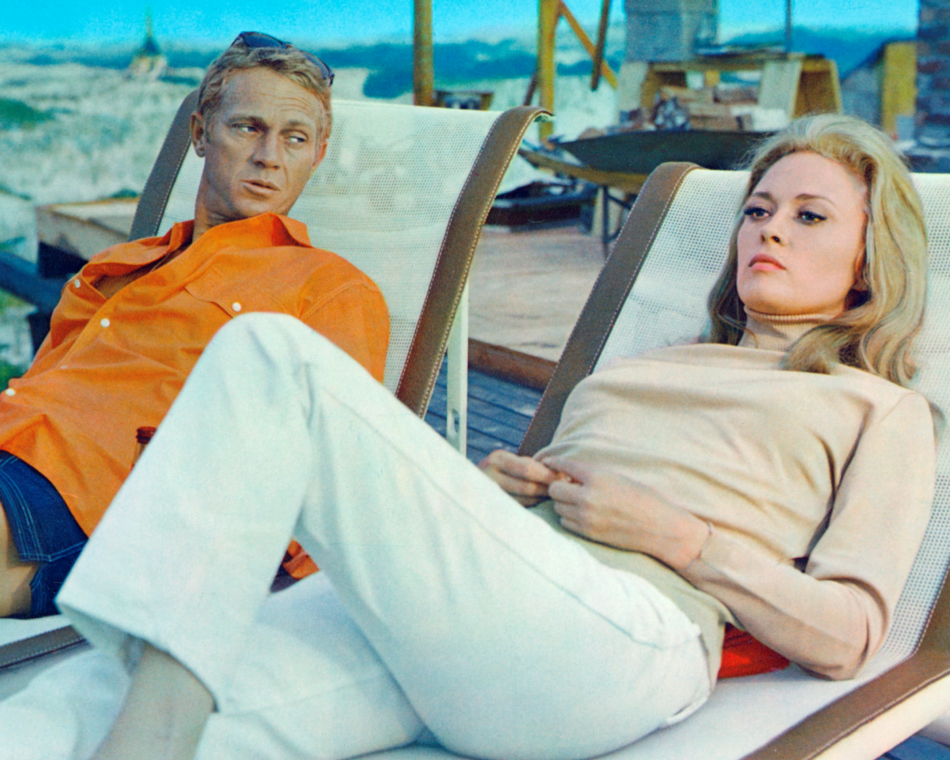

The Thomas Crown Affair

In dressing costars Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway for 1968’s The Thomas Crown Affair, costume designer Theodora Van Runkle took great pains to get the effect just right. “Sometimes, we had to put 30 pairs of trousers on [McQueen],” she told the Los Angeles Times in 1999, “to get the right ones to make his behind look great.”

Dunaway presented a different challenge. “Faye wanted the skirts to be right up to her crotch,” said Van Runkle. “We got into a knock-down, drag-out over it, and she won.”

Reviews of the Norman Jewison film were mixed, but even detractors hailed its breathtaking style. It helped, of course, to work with two of the most stunning stars in Hollywood — one playing a millionaire who carries out high-stakes bank robberies just for fun and the other a beautiful insurance investigator trying to catch him at his game.

While Dunaway’s miniskirts, suits and wide-brimmed hats reflected the youthful spirit of late 1960s women’s fashion, McQueen’s wardrobe presaged new trends. His three-piece suits were created by legendary tailor Douglas Hayward, who defined sophisticated suiting for the most dashing men of the era. They represented “a return to formality in menswear,” says Hughes. “It’s classic sportswear, not the anti-fashion of the late ‘60s. Moving into the 1970s, clothing takes on the idea of a ‘new masculinity,’ which was really about this dressed-up power suit.”

To many aficionados, McQueen’s accessories are the real standouts. His timepieces included a gold Patek Philippe pocket watch, a Jaeger-LeCoultre Memovox, and a Cartier Tank Cintrée. Then there was the eyewear — the Persol 714 folding sunglasses with Light Havana frames and crystal blue lenses were the actor’s personal favorite. Says Amerman, “When you look that good, you can get away with anything.”

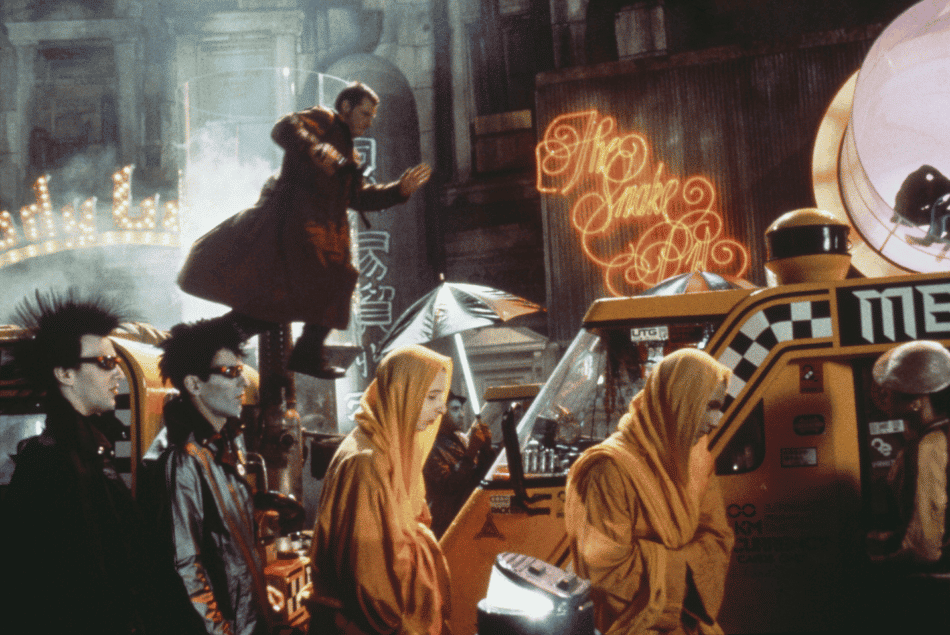

Blade Runner

For 1982’s Blade Runner, the task was to present a dystopian future in which enslaved robots, known as “replicants,” have lifetimes limited to four years lest they become powerful enough to overthrow humanity. Costume designer Michael Kaplan read the script and thought it was more Sam Spade, the private detective character in The Maltese Falcon and other films, than Star Wars. He sold director Ridley Scott on a film-noir approach to the wardrobes. “It was a bit of a whacked-out take on the 1940s that pushed the clothes into the future,” he later told The Independent.

So, Rachel (Sean Young) was given an updated Mildred Pierce hairstyle and swathed in fur, her hard wartime silhouette evoking Joan Crawford at her most disciplined. Daryl Hannah’s Pris, on the other hand, got a cyber-punk shock of cropped blonde hair, a leather dog collar and black-rimmed eyes. And then there’s Deckard (Harrison Ford), dressed in slouchy earth-toned ensembles reminiscent of Dashiell Hammett’s hero. Interestingly, as a blade runner, he’s expert at distinguishing between humans and replicants, and he just might discern one important tell: Replicants seem to dress much better.

Blade Runner inspired multiple fashion collections, among them Vivienne Westwood’s Spring/Summer 1983 Punkature; Alexander McQueen for Givenchy’s 1998 Fall/Winter haute couture; Jean Paul Gaultier’s 2009 Fall/Winter couture; Tomas Maier for Bottega Veneta Fall/Winter 2017 collection and Raf Simons’s Spring/Summer 2018 menswear.

“Blade Runner really did have an impact on designers who brought its sartorial narratives to the runway,” says Hughes, noting the slightly disturbing effect of the film’s approach to costuming. “Perhaps there will always be explorations of dystopia — but because they are not dressed in spacesuits, the end of the world feels like it may be a lot closer than we think.”

Marie Antoinette

A decade after its debut, the influence of Sofia Coppola’s 2006 Marie Antoinette was evident on the runways of Paris, New York, and Milan. “The S/S17 collections,” declared AnOther magazine, “prove that our love affair with sugar-coated style, like that of Sofia Coppola’s delectable teen queen, has never been so strong.”

The choice of adjectives was well considered, as the pastel colors of Milena Canonero’s Oscar-winning costumes were inspired by a box of Ladurée macarons given her by Coppola. The candy-colored costumes embodied Coppola’s focus on the pleasurable side of the young queen’s adventures.

Sure, there were long, troubled years when the court railed against a queen unable to seduce her king — but there were also parties, games, a handsome count, numerous pumps by Manolo Blahnik and oh-so-many pretty dresses. Kirsten Dunst portrays Marie Antoinette as a spirited teen enjoying the good times before angry crowds begin chanting “Madame Deficit.”

“Marie Antoinette captures a very female perspective,” says Hughes. Despite her royal title, the French monarch — in common with other women of her time — had very little real agency. Dress was both play and power. For the film’s audience, such indulgences provided vicarious thrills. “The fashion reflected the colors, embellishment and femininity that we were seeing in the early 2000s,” explains Hughes, “making this film an important marker of its time.”