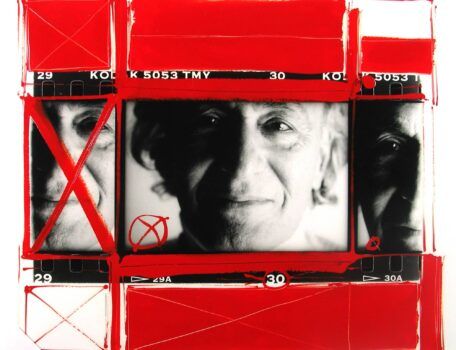

Top: Breuer Wassilys, 2016, acrylic painting on inkjet printed canvas, by Rochelle Udell. Bottom: Leather and chrome Wassily chairs, 1960s. Offered by Jean-Marc Fray

After executive-level careers in publishing, beauty and fashion, Rochelle Udell now creates art that asks viewers to reflect on the deep narratives contained in everyday objects.

The subject of her latest show, “Where Do You Sit In Life?” (on view at the 1stdibs Gallery in the New York Design Center until June 1), is chairs. The works encompass many mediums, from painting and collage to wallpaper and assemblage, all related to seating. But as the Ossining, New York–based artist reminds us, her series is just as much about what’s not seen, but implied.

“Sitting poses many questions with many possible answers: Who’s at the head of the table? Who’s at the center of the table? And who’s not even at the table?” Udell says. “Look, I’m not a chair scholar and I’m not a furniture scholar. I’m just a bit of a yenta who likes to watch how people behave, where they sit and how conversations form.”

The Study sat down with Udell to discuss the roles that chairs have played in her personal history and art. To illustrated her comments, we paired some of the works with real-world examples found on 1stdibs.

Left: P.S. 93 School Chair, 2016, acrylic painting on inkjet printed canvas. Right: Child’s school desk and chair, 1940. Offered by Abhaya

Udell’s exhibition is separated by themes like Everyday Icons (including historically important chairs represented in gold leaf), the Adirondack chair and poet Pablo Neruda’s “Ode to the Chair.” One section features three chairs that, Udell says, tell the story of her life thus far. P.S. 93 School Chair, for instance, is about Udell’s school days in the Bronx, where she recalls sitting down in a small seat that allowed her feet to touch the ground: “It was the first time I actually fit into a chair.”

The Adirondack Chair in the Grass, 2016, plastic molded relief with photo print, by Udell

Udell explains how she was completely mesmerized by the beauty and simplicity of the traditional Adirondack chair while attending summer camp as a young girl. “I’m a kid from concrete: Born in the Bronx, raised in Brooklyn. It was the first time I ever saw a chair that basically demanded you to relax,” she says. “It also struck me as a little, self-contained house. You could settle in, set down a drink and stack things up on its wide arms — and lean way back to read a book.”

Clockwise from top left: Canvas Wassily, Faux Fur Wassily, Sexy Sheer White Slip Cover and Faux Gold Chanel Wassily, all 2016

Several depictions of Marcel Breuer–designed Wassily chairs signal Udell’s coming of age. In her 20s, she moved into her first adult apartment and furnished it with a pair of Wassilys. “They represented modernity. They said I was a person of good taste and that I understood architecture and design,” Udell explains. “Then my mother walked in. . . . As far as she was concerned, these weren’t chairs because they didn’t have cushions or slipcovers.”

Somewhat perplexed by the streamlined chairs, her mom said, “Well, someday you’ll have a little money to cover them.” And so, years later, Udell did cover her Wassilys — with fake fur, plastic and vinyl. “If my mother said cover them, I was going to cover them!”

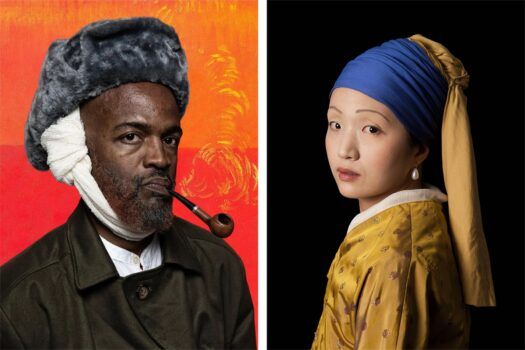

Top left: The Louie Chair, 2016, collage and ink on canvas, by Udell. Bottom right: Louis XVI fauteuil, ca. 1750. Offered by Gerald Bland

Udell cheekily associates different chairs with people in her life. For example, the Louis XVI chair represents the artist’s sister. “I have an older sister who always wanted to be a page in a magazine,” Udell quips. “If I was modern and minimalist, she was brocade and diamonds-are-a-girl’s-best-friend. She’s ornate, embellished, well dressed and has beautiful lines and lovely legs.”

Left: Set of Eight Loop Chairs 2016, gold leaf mono print on paper, by Udell. Right: Pair of Francis Elkins Loop chairs, 1940s. Offered by Craig Van Den Brulle

“The Frances Elkins loop chair is the absolute favorite chair of my dear friend, architect and writer James Shearron. He even wrote about it,” says Udell. “So if the Louis is my sister and the Adirondack is camp, then the loop chair is James. I can put faces on all the chairs.”

Udell has further elevated iconic chair designs by re-creating their shapes in gold leaf, a process she likens to a famous Leo Tolstoy witticism: “Truth, like gold, is to be obtained not by its growth, but by washing away from it all that is not gold.” In the process of removing the excess gold leafing from the surface of the paper, the artist leaves a ghostly silhouette of the chair. The result? Only the “gold” and “truth,” to which Tolstoy so literally refers.