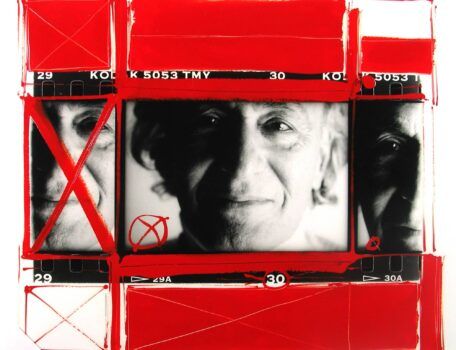

In his early adulthood, Simon Watson was restive. He’d gone to film school, but yearned to be a painter, and lacked the discipline to train himself in either field. “I was a lofty, tweed-wearing, Solzhenitsyn-reading, confused young fellow,” the Dublin native recalls. “I had a romantic view of things . . . and painting was very romantic to me then.” In 1988, when he was 20, he dropped out of school went to live abroad. He parents approved of this decision. Both were involved in the arts — his mother is, in fact, a painter — and so had sympathy for the often-awkward maturation of creative souls.

Watson spent more than a year footloose, perching for several months at a time in Paris, then Munich, then Barcelona, visiting museums, meeting new people, feeling out the wider world. By 1990, ready to further expand his horizons and recommit to painting, he set off for New York, hoping to immerse himself in what was then its vibrant youthful downtown art scene. Not long after he’d arrived, Watson got offered a job from an acquaintance to be the second assistant to a commercial photographer. By chance, then, he happened upon an entirely unexpected career.

Watson wasn’t new to photography. He’d been snapping pictures ever since his father gave him a 35mm Nikon when he was a teenager. For a time back then, he and a friend became preoccupied with photographing elderly ladies sitting on benches. The mystery of the women’s pasts captivated them, but only for a while.

In 1992, after a year and half learning the photography business as an assistant, Watson set off on his own. He spent a few months shopping portfolios around to little avail. Getting impatient, he called up Travel & Leisure. And pretending he was about to fly off to Paris for an assignment, he asked if the magazine needed anything shot there. It did, and thus began his long association with the publication. Soon after, Watson started shooting portraits of what he calls “interesting people” for W, assignments that also took him around the globe.

Where did this sudden tenacity come from? It was due, in part, to Watson’s newfound zeal for photography, but also the pressures of impending fatherhood — he had gotten his girlfriend pregnant and commercial photography was a more lucrative career bet than painting. (In addition to that child, a son, he and his girlfriend, who became his wife, also had a daughter, but they eventually divorced. Watson is currently married to the American photographer Christine Lebeck, with whom he has another daughter and a son. The family is based in Dublin.)

If he took awhile to mature, when Watson did, he did it quickly. During that sojourn, when he was seemingly loafing about Europe, his eye had been evolving. Once he embarked on his photography career, he shot images of great clarity and atmosphere, often edged in shadow, which were in every way his own. And art directors loved them. “Embrace the darkness,” Watson jokes, is something of a motto.

Interestingly, he never really looked to the photographic greats for inspiration, but instead to the Old Masters. “Van Eyck is very important to me,” says Watson. “I frame my photography in the same way he handles his portraits. Also important are the moody painters of the 17th and 18th centuries, like Pieter de Hooch and Jan Vermeer.”

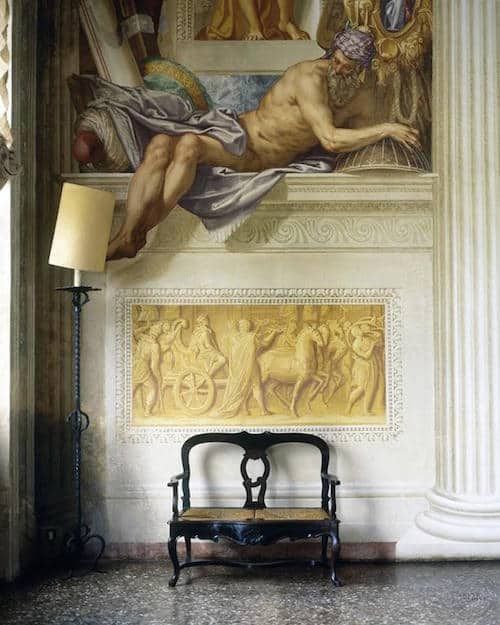

In those early years, Watson focused on building his reputation and traveled nonstop. On top of a growing list of editorial clients, he also added IBM, American Express and Mastercard to his corporate client roster. Yet successful as he became, he longed for more artistic work. A memory kept returning to him of being a boy of about ten waiting for the bus for school. “I would look into the stately windows of a row of shabby, grubby Georgian townhouses, with cheap, nasty net curtains and light streaming through from the back windows hitting the wood floor,” he recalls. “I was fascinated by the lives led in those spaces.”

Engrossed with “remembrances of things past,” he set off on a series of art photography projects, taking photos of rooms where a presence lingered. Some of the most compelling are the images he shot of interiors in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. “They’re creepy,” says Watson, in the way their everyday details contrast with signs of the disaster, like one of a dining table set for a meal bobbing in the flood waters.

But perhaps his most potent and haunting pictures come from the series portraying Auschwitz in Poland. In 2006, after much negotiation and planning, which required four visits, he shot rooms at the Nazi death camp that were not open to the public, which hadn’t been photographed since 1948. What’s so striking about the spaces, many of which are in the guards’ barracks, is that their crumbling, faded and streaked ocher and cerulean plaster walls are as beautiful as they are foreboding.

On assignment for Introspective magazine last year, Watson shot the Edinburgh studio and showroom of Stella and Issy Tennant.

“Melancholy plays an important part in my work,” notes Watson. “But it’s not necessarily negative, it’s often positive. Melancholy doesn’t have to be about darkness, there can be a solace to it.” The sentiment is distinctly Irish. As if to illustrate that point, as I interview Watson by phone from his home in Dublin, he observes that the weather has passed from blues skies to a massive hailstorm to heavy rain despite bright sunlight.

India will be the focus of Watson’s next art-photography project.