Across the nation this month, millions of historians, politicians and ballot-wielding citizens are marking the 100th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote in the United States. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment, thus enabling its adoption into the U.S. Constitution.

In case anyone needs a refresher, the amendment reads: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Sadly, because of the current pandemic, hundreds of planned celebratory events have been canceled. Author Doris Weatherford, whose most recent book, Victory for the Vote: The Fight for Women’s Suffrage and the Century That Followed, came out in February, admits to some disappointment. “For years, I’ve been talking about the centennial coming up,” Weatherford says, adding that she’d hoped the milestone would help to launch a revival of the larger feminist movement.

Whether or not her hope is realized, the anniversary offers us all a chance to take inspiration from our foremothers. It’s worth remembering that winning the vote was no easy victory. Women on both sides of the Atlantic faced ridicule, harassment and violence during 72 years of intensive struggle. For decades, these activists, known as suffragists, organized, lobbied, marched, picketed, protested and even held hunger strikes.

It’s also interesting to note that one of the most powerful yet stealthy weapons in their arsenal was style.

The word suffragette was coined in 1906 by a British reporter to mock women working for their suffrage. Although the militant wing of the movement embraced this name and began to use it to describe themselves, most preferred the term suffragist. To offset any sense that they were unladylike troublemakers, suffragists dressed conservatively in a fashionable and feminine style.

For demonstrations, women frequently wore all white. In 1908, suffragists in the United Kingdom adopted a signature color scheme of green, white and purple. Some say the palette represented the catchphrase “Give Women Votes,” with green standing in for the word “give,” white substituting for “women” and violet for “votes.” Others see the color green as representing hope, while white is for purity and purple for loyalty.

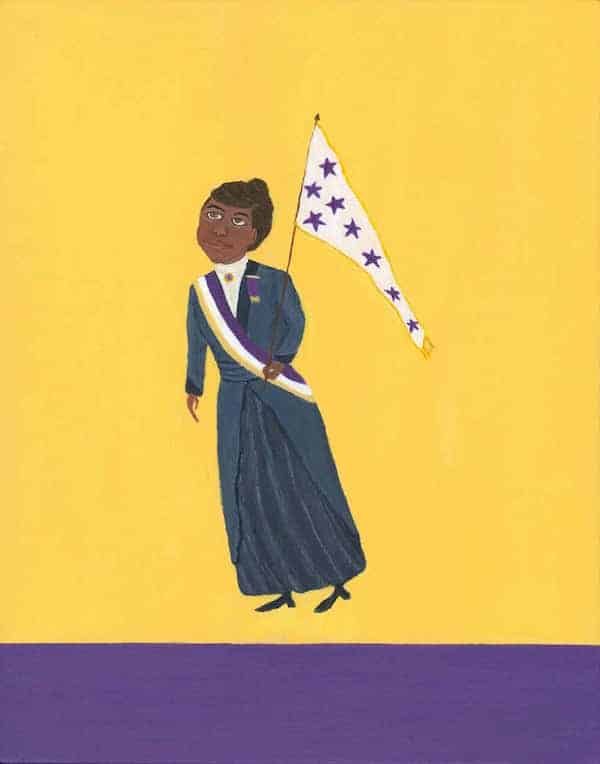

Mary Dwyer, a painter represented by the New York gallery Odetta, has created a series of striking suffragist portraits in a contemporary folk art style. “My paintings are a celebration of voter-rights activists and the visual pageantry of the suffrage movement,” Dwyer says.

While researching the American movement, Dwyer found women working simultaneously as suffragists, abolitionists and journalists. These activists published reports on voter disenfranchisement and racial inequality. “This diverse and multitalented group of women created a deliberate marketing campaign with buttons, ribbons, sashes, banners and flags. It was marketed by women for women.”

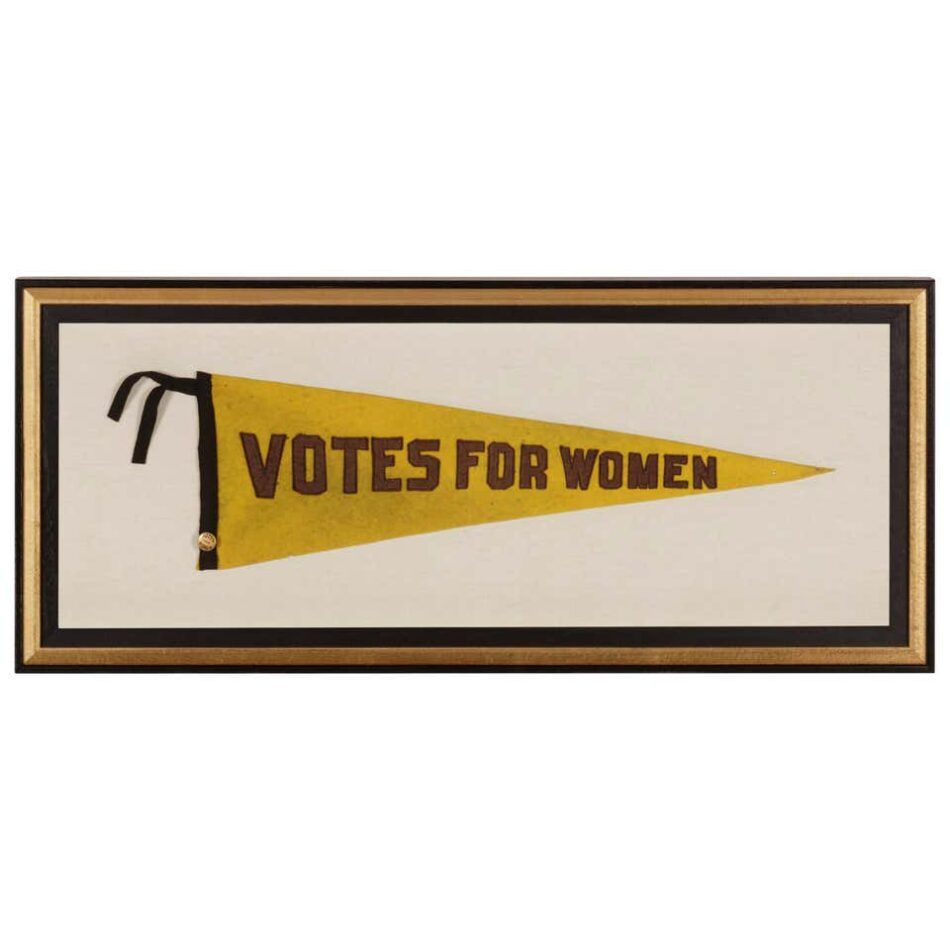

Jeff Bridgman, an antiques dealer based in York, Pennsylvania, and an expert on American flags and political textiles, points out that yellow was the customary color of women’s suffrage in the U.S., sometimes combined with other hues associated with the movement.

Perhaps because she had lived in England for 20 years, Harriot Eaton Stanton Blatch (1856–1940), the daughter of famed suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902), adopted purple and green to represent her New York City–based suffrage organization.

Bridgman believes that a large purple-and-green banner in his collection was probably used to encourage men to vote in one of four state referendums held in 1915. Overwhelmingly, however, the men of New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts voted to bar women from the polls.

A number of wealthy socialites, such as Alva Belmont (1853–1933), who married into the Vanderbilt family, supported the cause. Belmont founded or helped to found several suffragist groups and was known for attempting to integrate the movement by working with African American women.

She also had a reputation for building luxurious homes and throwing extravagant parties. She even commissioned a suffrage-themed English porcelain service (shown above) for events at Marble House, her mansion in Newport, Rhode Island.

While some supporters of suffrage attended fundraisers and marched in parades, others signaled their commitment in a subtler way, through their color-coded jewelry. In 1908, the British jeweler Mappin & Webb introduced a series of suffragette pieces, which inspired other makers to do the same.

Mallory Whitten, jewelry sales consultant at M.S. Rau, in New Orleans, explains that women wearing suffragette pieces “showed support for the movement but in a symbolic way,” to avoid backlash.

Whitten feels that suffragette jewelry, which was often crafted in peridot, amethyst and pearl, still has a message for us today. “This jewelry is a beautiful reminder of the strength and resilience of the women who came before us,” she says. “I hope that it inspires women now to continue to stand up and fight for our rights.”