Dogs have been inspiring artists for millennia. The ancient Egyptians depicted hunting dogs in stone carvings and murals and on clay vessels and tombstones, demonstrating a deep connection that rivaled their fondness for felines. Just as cats were believed to possess divine energy, domesticated dogs were seen as the sacred descendants of Anubis, the jackal-headed god of death who ensured the safe passage of the spiritual body into the afterlife.

Since ancient times, the unique bond between humans and their canine counterparts has found expression in every artistic discipline imaginable, from jewelry making and sculpture to photography and tapestry weaving. In Western portraiture in particular, dogs have betokened fidelity, protection, courage and friendship, as well as wealth and social status.

The British have both commissioned and collected portraits of dogs for centuries, as evidenced by a charming exhibition on view at the Wallace Collection, in London, through October 15. “Portraits of Dogs: From Gainsborough to Hockney” features masterpieces spanning from the Roman empire to the 21st century.

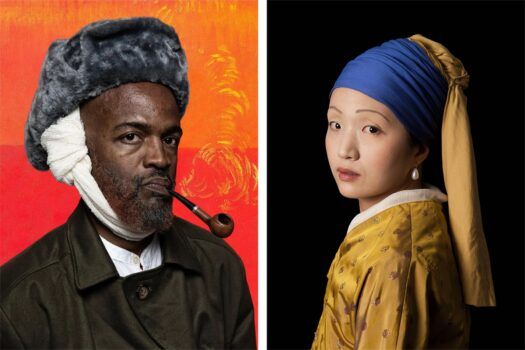

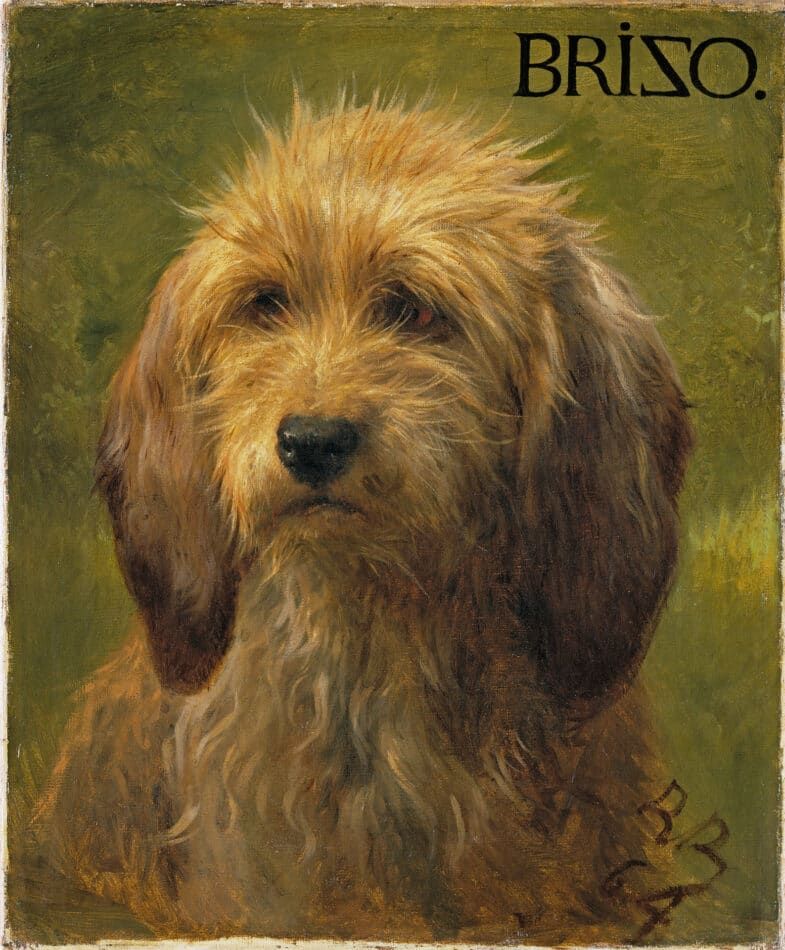

“The Wallace Collection lends itself perfectly to the staging of such an exhibition,” says the museum’s director, Dr. Xavier Bray (himself the proud owner of a pair of pugs, Bluebell and Winston). Bray explains that a brace of canvases from the institution’s holdings led the pack when it came to choosing the 59 works in the show. “Two of our most popular paintings are seminal dog portraits: Rosa Bonheur’s Brizo, a Shepherd’s Dog, 1864, and Edwin Landseer’s Doubtful Crumbs, 1858–59.”

According to Bray, the images represent two different approaches. “Bonheur’s portrait is a superbly lifelike and intimate portrayal of her French otterhound, Brizo. By contrast, Landseer is more interested in introducing a biblical parable into his portrayal, exemplifying the 19th-century urge to moralize through dog portraiture. In his work, a small street terrier waits for the ‘crumbs’ from the Saint Bernard, who falls asleep while feasting in his warm kennel — a Victorian moral of the rewards that await in heaven for the meek amongst us.”

Among the elites of 18th- and 19th-century Britain, handsome companion dogs and hunting hounds came to symbolize power and influence as the subjects of a new kind of society portrait, often painted against a suitably grand background, such as the plush interior of a stately home or the rambling hills of an aristocratic estate. Practitioners included Landseer, Thomas Gainsborough and even Britain’s consummate painter of horses, George Stubbs, who could not resist the charms of a spritely spaniel or two.

It was a woman, however, who proved to the art world that being a talented animalière was a worthy calling that could lead to great fame and fortune. Bonheur was the richest and most successful female artist of 19th-century France, known for hyperrealistic wildlife scenes and imbuing animals with near-human emotions. The painting of Brizo captures every nuance of her pet’s sweet, shaggy appearance with lifelike precision.

One of Bonheur’s biggest admirers was Queen Victoria, who also dabbled in animal art. A selection of the monarch’s charming (if somewhat less accomplished) watercolors and etchings are on display in the show, highlighting her love of petite purebreds, including Podge the Scotch terrier and Waldmann the dachshund.

In fact, puppy love was so prevalent in Victorian society that canines were immortalized in other forms of creative expression. The fox-like profile of a feisty white German spitz adorns a mid-19th century brooch by an unknown maker. Enameled jewelry embellished with miniature portraits of pampered pooches was extremely en vogue in Europe at the time, popularized by the micromosaic expert and Vatican artist Antonio Aguatti.

Several even older treasures shed light on the human-canine bond that quickly followed the domestication of wild dogs, originally for hunting. These include a first-century Roman marble sculpture known as the Townley Greyhounds, on loan from the British Museum, and a study of a deerhound’s paws by Leonardo da Vinci.

Other artworks offer glimpses into their creators’ private lives, such as David Hockney’s colorful portraits of his adored sausage dogs, Stanley and Boodgie, the ever-dozy subjects of his 1995 series “Dog Days.”

Perhaps Britain’s most famous animal lover was Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, who famously said, “My corgis are my family.” The royal attachment is explored in “The Queen and Her Corgis,” a separate photographic exhibition dedicated to the late monarch and her passion for that distinctly British breed, noted for its chipper smile and stumpy legs.

The earliest image on view, from July 1936, shows the young Princess Elizabeth playing in the large garden of her childhood residence, 145 Piccadilly, with the first royal Pembroke Welsh corgis, Jane and Dookie. Another photograph, taken in May 1944, captures her holding her corgi Susan on the grounds of Windsor Castle; the pup, an 18th-birthday gift from her parents, was the first of 30 corgis she kept during her reign.

Of course, the pulling power of these two exhibitions, and indeed the enduring popularity of this genre, is all down to the unconditional love that dogs offer us, which in turn connects us to our more thoughtful, affectionate selves.

British realist artist Lucian Freud was certainly aware of the relaxed quality dogs brought to his compositions. Known for his fondness for animals and especially whippets, Freud often featured his own beloved dogs in his paintings, nestled in the crook of an arm or elegantly stretched against the reclining form of one of his human sitters.

“I like people to look as natural and as physically at ease as animals — as Pluto, my whippet,” Freud once said, sharing a sentiment that makes his 2003 painting Pluto’s Grave, on display in the main exhibition, all the more heart-wrenching. A bitter-sweet tribute to his faithful companion, the canvas shows the dog’s tombstone surrounded by dead leaves, sheltered by a flush of luscious green bamboo. More than a message about personal grief or a meditation on mortality, the painting stands as a poignant reminder of the sheer joy that a dog can bring to a human life.

Perhaps Hockney said it best when describing the series featuring his two favorite muses, Stanley and Boodgie. “They’re like little people to me,” he explained. “The subject wasn’t dogs but my love of the little creatures.”