1. Feminists protested a monumental Gaetano Pesce sculpture during Salone

December 15, 2019Gaetano Pesce’s 26-foot sculpture Maestà Sofferente (Suffering Majesty) in Piazza del Duomo during Milan Design Week. Photo by Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images

This year, the gender wars broke out smack in the middle of Milan Design Week, when B&B Italia unveiled Maestà Sofferente (Suffering Majesty), a 26-foot sculpture by Gaetano Pesce propped up in Piazza del Duomo. The piece was a reinvention of Pesce’s iconic Up armchair, which is shaped like the torso of a voluptuous woman chained to a ball-shaped ottoman. “The woman is a prisoner of men’s prejudice and oppression,” Pesce told us of his 1969 design, a masterpiece in polyurethane.

Fifty years after the chair’s debut, his installation took that theme to an extreme, piercing a massive, flesh-colored Up seat with a flurry of arrows that he said were meant to draw attention to the persecution of women persisting today. Italian feminist group Non Una Di Meno (Not One Less) protested the new work. “The woman is represented as helpless and victimized, without calling into question the actor of the violence,” the group said in a statement.

Pesce didn’t apologize and instead defended the piece. “I believe these feminists have not read nor understood the meaning of my work in Milan,” he told Dezeen. “Generally speaking, when two entities fight for the same objective, they cooperate.” Regardless of the recent controversy, the original Up chair is certainly worth celebrating. — Liz Logan

2. The landmark TWA Flight Center reopened as a hotel

Visitors to the Sunken Lounge and the Paris Café at the TWA Hotel can sip cocktails while watching planes take off. Photo by David Mitchell/TWA Hotel

Eero Saarinen’s swooping, audacious design for the TWA Flight Center at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport captured the spirit and the optimism of the Jet Age when it opened, in 1962. This May, after lying dormant for nearly two decades, the landmark terminal took flight as the new TWA Hotel. Every detail, down to the ceramic penny-tile floors and chili pepper red palette, celebrates the idealism and glamour of the postwar period and the Finnish-American designer who captured it in curvaceous concrete form.

The two new wings — designed by Lubrano Ciavarra Architects with 86 suites and windows boasting the world’s second-thickest panes, surpassed only by those of the U.S. Embassy in London — curve gently behind the original Flight Center, which serves as the hotel’s arrival point. Inside, guests can sit on stools amid Saarinen-designed Tulip tables in the restored Sunken Lounge and stare out through the glass curtain wall at arriving and departing flights, as well as at the Connie, a 1958 Lockheed Constellation reimagined as a cocktail lounge and parked on the tarmac outside. Just as Saarinen intended. — Joann Plockova

3. Gaga wore the priceless Tiffany Diamond

Lady Gaga wearing the Tiffany Diamond at the 91st annual Academy Awards ceremony. Photo by Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic

Actresses routinely turn up in 5, 10 or even 20 million dollars worth of jewelry at the Oscars, but no one has ever worn something as valuable as Lady Gaga did this year. The Star Is Born actress made jewelry history when she stepped onto the red carpet in the 128.54-carat Tiffany Diamond. The gem, one of the largest and finest yellow diamonds in the world, is literally priceless, because it’s not for sale.

It was purchased as a piece of rough by Tiffany & Co. founder Charles Lewis Tiffany in 1877. After having the stone hand-cut into a chunky cushion-shape, the visionary jeweler decided not to sell it. Instead, he put it on display in his store, clearly announcing that Tiffany was the diamond authority.

Over the years, the diamond has been worn outside the store only once, in 1957, by a client who donned it for a charitable fundraiser. In 1961, it appeared briefly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s in a scene shot in the store. On occasion, the gem makes special appearances at Tiffany & Co. boutiques around the world and in museum exhibitions. How it is transported from one location to the next is a closely guarded secret.

In fact, the security surrounding Lady Gaga at the Oscars — and at the after-parties and Madonna’s after-after-party, where she also sported the jewel — was the subject of heated media speculation. Everyone agreed there must have been guards everywhere, in the audience and on stage. Everywhere. All in all, it was a night for jewelry lovers to remember, and one the security detail will surely never forget. — Marion Fasel

4. Designers worked with nature to reverse planetary destruction

Xu Tiantian’s Bamboo Theater, shown in a film in the Cooper Hewitt triennial exhibition “Nature,” is a living structure in rural China. Photo courtesy of Cooper Hewitt

For those of us haunted by David Wallace-Wells’s frankly terrifying predictions about our planet’s habitability if we don’t act to slow the ominous progress of climate change, the spring opening of this year’s triennial exhibition at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, arrived as a soothing balm. Titled “Nature” and developed with the Netherlands’ Cube Design Museum, it showcased the ingenuity of designers around the globe working with the natural world to critically examine and solve the problems that plague it and us.

Visually stunning and environmentally sophisticated projects like Sam Van Aken’s Tree of 40 Fruit, a living tree on museum grounds altered through the science of grafting to offer more varieties of fruit than your average Trader Joe’s, and architecture firm Terreform ONE’s Monarch Sanctuary, a planned eight-story commercial building that will double as an ideal habitat for the increasingly threatened pollinators, demonstrated the myriad ways that humans can apply the same passion for innovation that led us this far down the garden path to help walk us back toward the wilderness. — Karen Quarles

5. The house in Parasite gave an Oscar-worthy performance

The setting for the sleeper hit film Parasite is a contemporary glass and concrete house. Courtesy of NEON

The Oscar for Best Supporting Architecture goes to: the house in Korean director Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite. It’s hard to think of another movie in which a single building has played such an important role. The film, critics have pointed out, operates on multiple levels — not all of them obvious at first — and the same might be said of the spectacular glass and concrete dwelling.

Although it is presented as the work of the (fictional) architect Namgoong (and is actually the creation of production designer Lee Ha Jan), the house could have been designed by Tadao Ando, the Japanese Pritzker Prize winner known for his elemental forms and smooth-as-silk concrete.

In Bong’s film, the house’s clean lines telegraph its owners’ upper-class sophistication. At the same time, its tranquility makes the chaos that engulfs those owners all the more disturbing. Lee gave the living room a vast picture window and only two pieces of furniture — one of them a coffee table that becomes essential to the plot. No spoilers here, except this leading question: Does your next house really need a basement? — Fred Bernstein

6. Mid-century design lost one last pioneer

Clockwise from right: Florence Knoll with her dog Cartree in 1950; gray Florence Knoll lounge chair, 1961; pair of red Florence Knoll lounge chairs, 1961; Hairpin tables, 1948; Parallel Bar lounge chair, 1951. Photos courtesy of Knoll Archive

For lovers of mid-century modernism, the death of Florence Knoll Bassett in January at 101 marked the end not just of a life but of an era. The designer and entrepreneur (better known as Florence Knoll), who founded Knoll Associates with her husband, Hans Knoll, and went on to lead the company after his death, in 1955, introduced many of the postwar period’s signature pieces and introduced a now-ubiquitous corporate aesthetic of open floor plans and clean lines.

Immersed in modern architecture almost from birth, the Michigan native was a close childhood friend of the Saarinen family and later studied with Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. She was modest about her own designs for Knoll, which she said amounted to “meat and potatoes,” but curators and connoisseurs would beg to differ. They endure, as does the impact of her exceptional eye, evident in every office with a Bertoia chair or a Saarinen tulip table, which is to say most of them. — Karen Rosenberg

7. MoMA got bigger and rejiggered its collection

New spaces in the expanded Museum of Modern Art include the day-lit second-floor gallery, installed with Sheela Gowda’s Of All People, 2011 (left side), and the projects gallery, currently featuring eight paintings by Michael Armitage (lower right). Photo by Iwan Baan, Courtesy of MoMA

In October, New York’s Museum of Modern Art reopened after closing for four months, having spent $450 million on new galleries that increase exhibition space by a third. The architecture, by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, is clever, stylish and art-friendly, but the rehang of the permanent collection may be the most significant change.

A room full of Matisses, which you’d expect, now includes a beguiling canvas by the African-American painter Alma Thomas, which you wouldn’t. A ceramic piece by George Orr, the “mad potter of Biloxi,” displayed across from van Gogh’s Starry Night? The curators gave it a go in an effort to retell and diversify the story of 20th- and 21st-century art.

For fans of the museum’s lauded Architecture & Design collection, it’ll be a difficult adjustment, with presentations of the material integrated into the rest of the collection on the second, fifth and sixth floors. For best results, go in with an open mind — and an open schedule, since it takes some time to experience the new, expanded MoMA. — Ted Loos

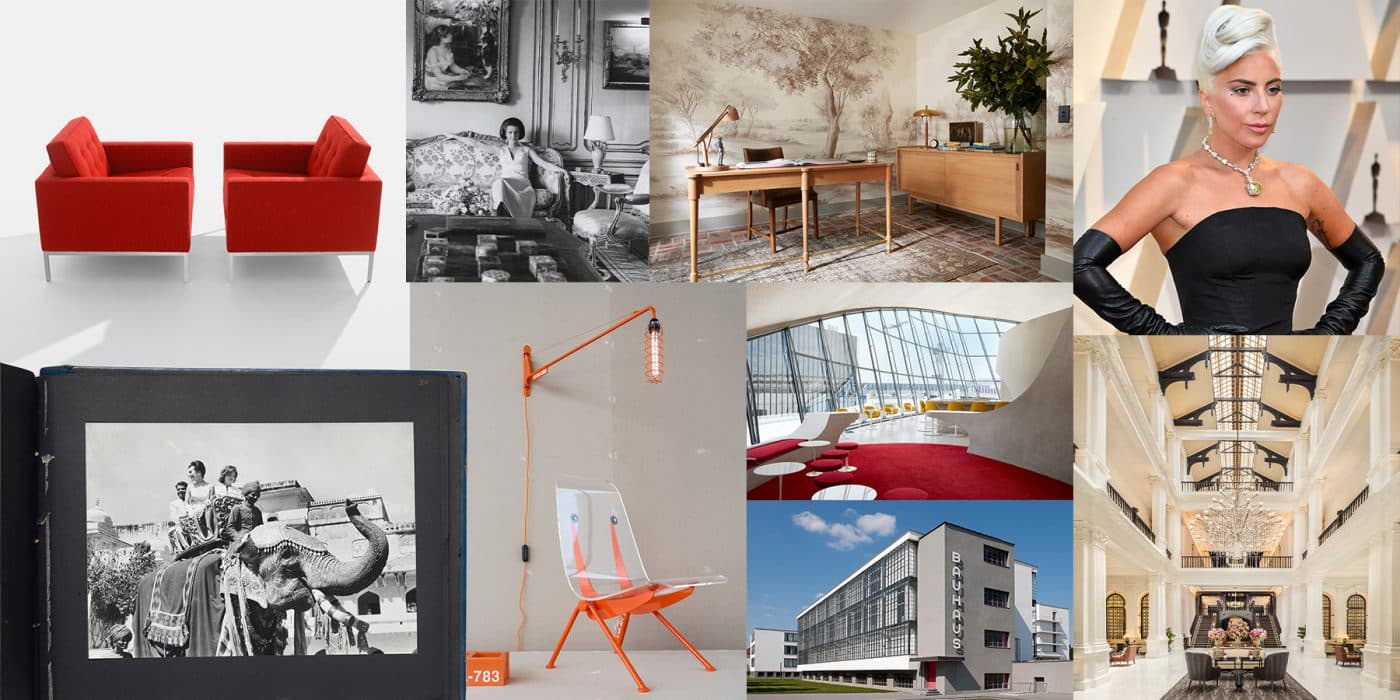

8. Virgil Abloh entered the furniture game

Virgil Abloh (left) launched a collection for Vitra that included limited-edition orange bricks and the Antony chair (right). Portrait by Joshua Osborne; right-hand photo by Marc Eggimann

Twenty nineteen was yet another fabulous year in the Age of Virgil Abloh. Just 39, the Ghanaian American stands unrivaled at the planetary intersection of art and commerce. An architect by training, the self-proclaimed “hypercreative” inverts fashion, design, music and prose with seeming ease, deftly twisting personal and cultural preconceptions around his witty fingers — blurring lines, engaging our senses.

The founder of fashion company Off-White and artistic director of menswear at Louis Vuitton, Abloh had his first museum exhibition in June at the MCA, in Chicago, his hometown. Called “Figures of Speech,” the whole show embodied conceptual irony, as the visitor could imagine quotation marks around each display, whether Abloh used them or not. The exhibition’s run was extended, and it is currently at the High Museum of Art, in Atlanta.

Then there was Abloh’s collaboration with Swiss furniture company Vitra. TWENTYTHIRTYFIVE launched during Art Basel with a DJ set by Abloh on the Vitra campus, as well as an art installation and three sold-out limited-edition home-design products. One of the resulting pieces is Antony, an orange-lacquered armchair with a Plexiglas shell inspired by Jean Prouvé’s 1950s seat of the same name.

November brought the Markerad collection Abloh created with Ikea, which comprises 13 affordable pieces, including a green fluffy rug featuring the warning WET GRASS. The carpet was displayed at the MCA with a video of Abloh watering it. Is it art? Or “art”? Nothing is off-limits for Abloh. — Clair Watson

9. Jean Nouvel’s UFO-like National Museum of Qatar rose in Doha

Aerial view of the National Museum of Qatar, in Doha. Photo by Iwan Baan

Even among the other starchitect-designed cultural institutions that have sprung up across Arabian capitals in recent years, Doha’s new National Museum of Qatar stands out. To create the sprawling, 560,000-square-foot building, which opened in March, Pritzker Prize winner Jean Nouvel translated the organic form of a desert rose — whose radiating crystal clusters form just below the surface of salt basins — into a series of interlocking concrete disks of various sizes.

These cascade across the museum’s campus, which is situated between the city center and a busy highway and looks like a cross between a sand dune and a UFO landing site, at once familiar and strange. The talent behind Dubai’s branch of the Louvre and Paris’s Institut du Monde Arabe, Nouvel has described the desert rose as “the first architectural structure that nature itself creates.” Here, he used it to stunning effect, carving a series of spaces that together tell the story of Qatar through art, archaeology, film, poetry, music and more. — Andrew Sessa

10. Lady Hale’s spider brooch went viral

Lady Brenda Hale in her now-famous spider brooch. Photo by Kevin Leighton/Supreme Court of the United Kingdom

Lady Brenda Hale, president of the British Supreme Court, became an unwitting fashion icon in September when she announced her ruling that Boris Johnson had illegally suspended Parliament. The source of her new style status? A dazzling diamanté spider brooch pinned at the shoulder of her sober black dress. It didn’t take long for Lady Hale’s jewel to become a viral sensation: Memes and trompe l’oeil spider brooch T-shirts quickly surfaced, and in the United Kingdom, Internet searches for animal brooches spiked 126 percent.

Twitter was ablaze with speculation as to the jewel’s significance. Some suspected a reference to the Who’s 1966 song “Boris the Spider”; others quoted an 1808 Walter Scott poem: “Oh, what a tangled web we weave/When first we practice to deceive!” After years of being dismissed as dowdy, pins have been experiencing a renaissance among contemporary jewelry and fashion designers. Now, thanks to Lady Hale, the brooch has cemented its place as the ultimate power jewel. — Kareem Rashed

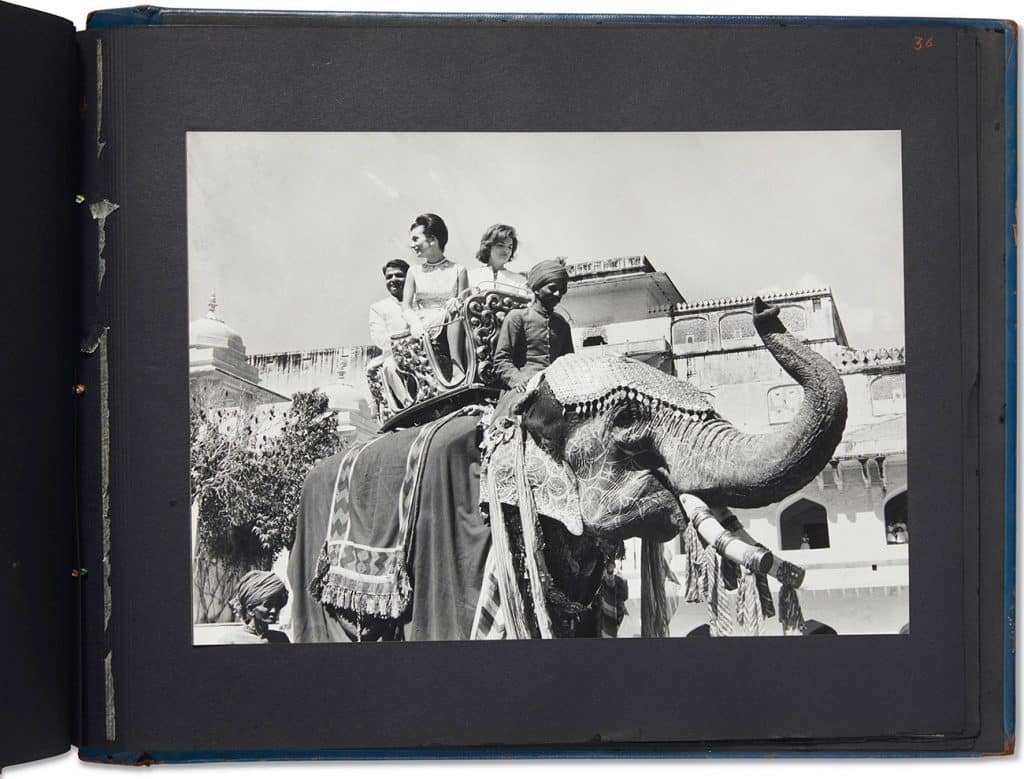

11. The Bauhaus turned 100 — Modernism is officially antique

The Bauhaus building in Dessau, Germany. Photo by Tadashi Okochi © Pen Magazine

Was anything so short-lived ever so influential as the Bauhaus? The German architecture and design school, founded in 1919 and shuttered by the Nazis 14 years later, shaped the modern age as we know it, ushering out an era of ornate furniture and substituting streamlined pieces at democratic prices — things we take for granted today.

The centennial year was jam-packed with exhibitions and events, capped by two major museum openings. The newly built Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, three hours south of Berlin, where the Bauhaus began, houses such classic designs as Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel chairs and tables, along with lamps, pottery, weavings and wallpaper by other Bauhaus luminaries.

The still-under-construction Bauhaus Museum in Dessau, site of the school’s 1925–32 heyday under Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, centers on Gropius’s iconic glass-faced Bauhaus building and the cubic Masters Houses where László Moholy-Nagy, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee lived with their families in the ultimate artists’ colony.

Germany’s central Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt regions haven’t been on many European travel itineraries. Redubbed “Bauhausland” by local tourist boards, they are now pilgrimage sites for fans of modernism. — Cara Greenberg

12. The opulent Wrightsman co-op went on the market

Jayne Wrightsman surrounded by her fine French furniture and art in her New York apartment. Photo by Cecil Beaton © Conde Nast

When it comes to 20th-century art patronage, you could hardly beat Charles and Jayne Wrightsman, who endowed the Metropolitan Museum of Art with exquisite Louis XV and XVI furnishings, gowns by Balenciaga and Lagerfeld and paintings by — among others — de la Tour, Tiepolo, Vermeer, Delacroix, Rubens and Pissarro. Their largesse and erudition also extended to the Morgan Library, the British Museum, the Louvre and the Hermitage.

Now, the epicenter of that extraordinary philanthropy, the Wrightsmans’ sumptuous 7,000-square-foot Fifth Avenue apartment overlooking Central Park, is on the market following Jayne’s death, in April, at 99. The price tag is $50 million ($23,729 monthly maintenance) — cash.

Working with the legendary Parisian decorator Maison Jansen, Jayne appointed the five-bedroom residence with imported parquet de Versailles floors, ornate boiseries, 18th-century marble mantels and floral wallcoverings (all still in place), then filled it with priceless furnishings and art. A separate two-bedroom apartment the couple purchased for staff is also on offer, for $2.5 million. — Jorge Arango

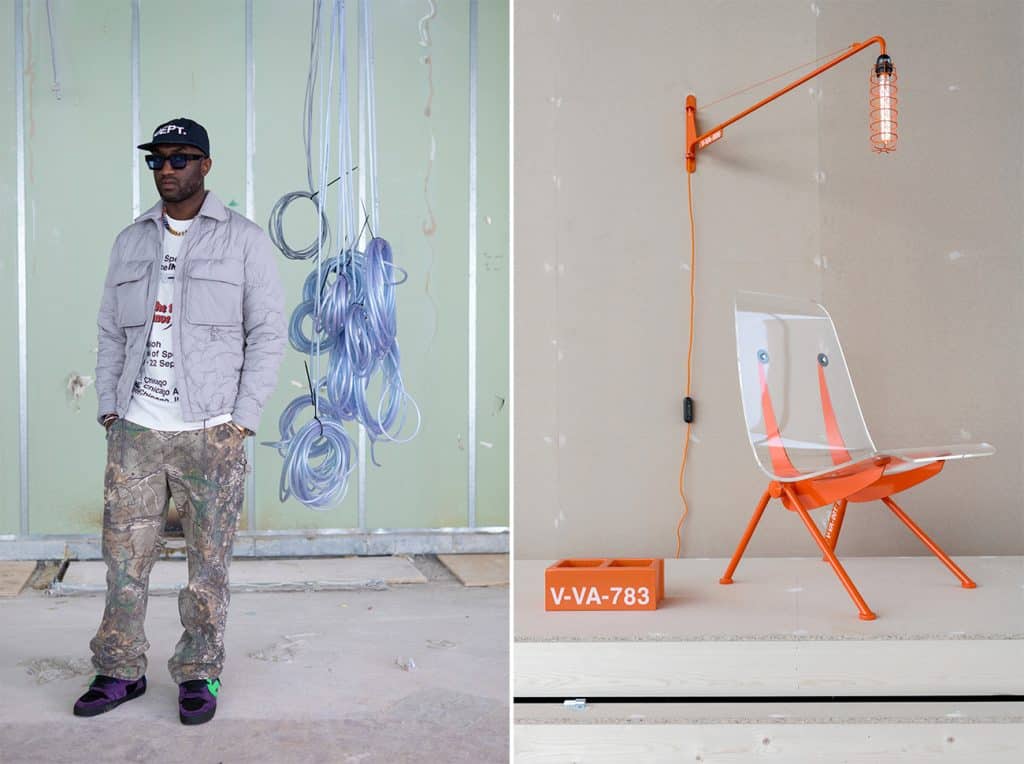

13. The novel The Dutch House brought a 1920s home to vivid life

Cover of The Dutch House by Ann Patchett. Photo courtesy of Harper

I’m a lifelong lover of design — and literature — so give me a novel with a house as compelling and vividly portrayed as the human characters who inhabit it, and I’ll settle in quite happily.

Among recent reads, none has a more evocative literary structure, if you’ll excuse the phrase, than 2019’s The Dutch House (Harper), by Ann Patchett, in which a grand 1920s home in a tony Philadelphia suburb is both refuge and root of unhappiness for the book’s young brother-and-sister protagonists.

“Seen from certain vantage points it appeared to float several inches above the hill it sat on,” Patchett writes. “The panes of glass that surrounded the glass front doors were as big as storefront windows and held in place by wrought-iron vines. The windows both took in the sun and reflected it back across the wide lawn.”

Inside are portrait-lined hallways, a dining room with a frescoed ceiling, a ballroom (on the third floor, no less), Delft-tiled mantels throughout and a curtained window seat in a daughter’s bedroom that would make Jane Eyre jealous. There’s also a cozy kitchen with a blue-Formica table where a kindly cook “sat and shelled peas or rolled out pie dough.”

Distinctive though it may be, Patchett’s Dutch house gives shelter to the same pain and pleasure and domestic dramas likely felt in any home in which a family dwells. — Anthony Barzilay Freund

14. Singapore’s 132-year-old Raffles Hotel got a facelift

Grand Lobby of the Raffles Singapore revamped by Champalimaud Design. Photo courtesy of the Raffles Singapore

Commendable is the designer who inherits a national monument and practices restraint. Alexandra Champalimaud and her team did just that in their superb redesign of the Raffles Singapore, the 132-year-old luxury hotel with sweeping verandas that is credited both as the first property to introduce private butlers for guests and as the birthplace of the Singapore Sling.

In August, the iconic institution reopened following a meticulous restoration that lasted more than two years. Champalimaud Design delivered majesty for modern tastes. “We want the guests to experience the timelessness of the hotel but also something new, elevated, and very real,” Champalimaud says.

The luminous Grand Lobby features contrasting black elements — railings, arches and accents — reminding you to look around. The design team honored the colonial architecture, maintaining 19th-century attributes while delivering a clean edit. The guest suites have traded their previous pigmented matte look for beauty that breathes. The story gets moodier in the Writers Bar and slinky new La Dame de Pic restaurant, where a plum, pink and gray palette purrs beneath the ceiling’s peony bas relief. Purists will be happy to know the famed Long Bar staircase was restored. Essentially, Raffles received the sort of modern makeover we all want: an age-appropriate one. — Arianne Nardo

15. Mughal jewels dazzled new audiences

Jewels from the Christie’s auction Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence. Photo courtesy of Christie’s

The jewelry world was sent into a collective tizzy when, unexpectedly, Christie’s announced the sale in June of nearly 400 important Mughal jewels and decorative objects. Drawn from the Al Thani collection, an unparalleled trove of Indian jewelry that has been exhibited in museums around the world, the lots included a number of sensational works — among them, gob-stopping Golconda diamonds, Art Deco emerald and sapphire treasures by Cartier and contemporary riffs on Mughal design by modern masters like JAR and Bhagat.

Realizing a total of $109,271,875, Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence set a record for an auction of Indian art and was the second-highest-grossing sale of a private jewelry collection ever — bested by that of none other than Elizabeth Taylor.

If that weren’t enough to put Mughal style firmly in the spotlight, Paris’s musée des Arts décoratifs mounted “Moderne Maharajah” in September, showcasing the maharaja of Indore’s incomparable collection of design. The Indian prince and international tastemaker commissioned a staggering array of works by pioneering talents of the 1920s and ’30s, including Jean Puiforcat and Le Corbusier. His jewels from houses like Van Cleef & Arpels and Chaumet, marrying Western modernism with Mughal opulence, underscore the incredible (and enduring) influence India has had on jewelry design. — Kareem Rashed

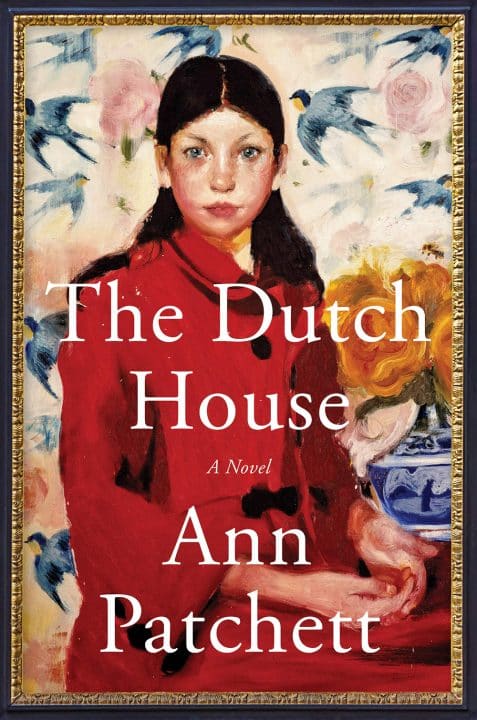

16. The Bouvier sisters held big sales

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s Red Gate Farm in Martha’s Vineyard was offered up for sale with a price tag of $65 million. Photo courtesy of Christie’s International Real Estate

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Lee Radziwill. A first lady and a Polish princess. Was there ever a more dazzling pair of American sisters than the Bouviers? The strength of their sibling bond was as enduring as their rivalry as style setters and inamoratas of some of the world’s most glamorous and wealthy men. Yet each eventually advanced beyond titles and partners to become quiet cultural forces in her own right: Jackie in book publishing and Lee in decorating and fashion.

Although Lee joined her sister among the heavenly beau monde earlier this year, their dueling for the spotlight as tastemakers continued. This summer, Red Gate Farm, Jacquie’s 340-acre sanctum situated in the most remote reaches of Martha’s Vineyard, went on the market for an eye-catching $65 million. Of course, its style pedigree was impeccable: The lauded vernacular modernist Hugh Newell Jacobsen remodeled the original farmhouse, which was later freshened by acclaimed architect Deborah Berke, and gardening’s grand dame Bunny Mellon landscaped the grounds.

The bound photo book Visit of Mrs. John F. Kennedy to India, March 1962 sold for $50,000 at the Lee Radziwill auction. Photo courtesy of Christie’s

Then, in October, the contents of Lee’s Upper East Side apartment, more than 150 lots of photographs, furniture, art, jewelry and memorabilia, went on the block at Christie’s in one of the fall’s most anticipated sales. Two pairs of the oblong Gucci sunglasses favored by both Lee and her sister sold for a total of $2,750; a bound book of photographs of their historic trip to India went for $50,000. In all, the auction brought in $1.26 million — quite a sum for the contents of a single woman’s pied-à-terre, yet it a pales in comparison to the sum potentially netted by Jackie’s estate. Lee, as always, is being outshone by her older sister. — Marisa Bartolucci

17. Ikigai replaced hygge as a major international lifestyle fad

This Los Angeles home office designed by Nickey Kehoe Design embodies the spirit of ikigai. Photo by Roger Davies

For several years, Americans lovingly embraced the difficult-to-pronounce Danish way of life known as hygge. Connoting coziness, hygge made us feel swaddled in pure comfort and joy. In 2019, we turned to the Japanese for lifestyle inspiration, adopting ikigai, which loosely translates as “reason for being.” Tim Tamashiro, author of How to Ikigai: Lessons for Finding Happiness and Living Your Life’s Purpose (published in January by Mango), explains it as “a map that can help lead you to a more meaningful life.”

For interior designers and their clients, every step of the process can be an act of ikigai. According to Tamashiro, “You can design a wardrobe, design the elements of a garden, the centerpiece of a dinner table or the way your boots are stored at the front door. To design is to plan, imagine, implement or create. It relates to thoughtful care and attention for beauty and functionality.” Designers enhance their clients’ ikigai by creating spaces they’ll love to live in, and enhance their own ikigai by pursuing their passion for design. — Jess Cherner

18. Hudson Yards got schooled by Essex Crossing on how to develop a new neighborhood

The shiny skyscrapers of Hudson Yards rising in the distance. Courtesy of Hudson Yards

Thomas Heatherwick’s Vessel, with its 154 staircases to nowhere, wasn’t enough to save Hudson Yards from critical disdain. Nor was the Shed, an expandable performance/exhibition space, designed by terrific architects — Diller Scofidio + Renfro with Rockwell Group — but with no obvious raison d’être. The $25 billion development, mostly high-end condos arranged around a lackluster “park” and a surprisingly ordinary mall, was dubbed Dubai (or perhaps Do-buy) on the Hudson.

The pedestrian-friendly Market Line at Essex Crossing. Courtesy of Essex Crossing

For an example of how to do it right, head two miles southeast to Essex Crossing, on Delancey Street. There, a six-acre plot of former parking lots has sprouted a variety of housing types, from market-rate condos to affordable rental units, along with real amenities like the Essex Market, smartly updated by SHoP Architects; a photography museum; a multiplex cinema; the largest rooftop farm in New York; and open spaces that make people want to hang around. Only one development deserves to use Hudson Yards’ slogan, “New York’s Newest Neighborhood,” and it isn’t Hudson Yards. — F.B.

19. 1stdibs users loved these items most

Six of the most popular pieces on 1stdibs this past year.

Among the nearly one million items that could be found on 1stdibs during 2019 — running the gamut from antique and vintage treasures to the latest in new or customizable design — the above six were what we have deemed “most popular” based on the number of sales and/or frequency with which they were saved to a folder or favorited by our six million monthly visitors.

The grouping accords with the findings of the design-trends survey we conducted at the start of the year, which discerned trending interest in decor characterized by woven materials (Børge Mogensen’s oak and cane 2254 lounge chair, 1956, and Sebastian Muggenthaler’s teak and rattan wardrobe, 1960), jewel tones (Sander Bottinga Green Charme pendant lamp) and a sense of humor (Seletti’s Lipsticks wall mirror, Faye Toogood’s Polyethylene Roly Poly armchair).

As for the Edwardian tiara‘s appearance on the list, one can perhaps attribute that to diamonds’ truly being forever or the enduring interest, among the aesthetes and design-history buffs who frequent 1stdibs, in Netflix’s The Crown. Check in same time next year to see what’s crowned most popular in 2020. — A.B.F.