July 20, 2025It’s been a long time since mid-century modern style first made its mark on our design consciousness. And with so many later iterations pervading the marketplace, we might be excused for not knowing more about its early years.

The exhibition “Eventually Everything Connects: Mid-Century Modern Design in the US,” on view at the Cranbrook Art Museum, in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, June 14 through September 21, is a fine refresher course on the birth of an aesthetic that shows no sign of falling out of favor.

The museum is, of course, associated with the celebrated Cranbrook Academy of Art. Charles Eames, once head of the school’s industrial design department, is reported to have said, “Eventually everything connects — people, ideas, objects. The quality of the connections is the key to quality per se.” The show fashions its conceit from his remark, highlighting the often overlapping connections among mid-century modern designers, artists and architects — a number of whom were linked to Cranbrook.

Headed by Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, the academy emerged as an incubator of progressive design in the 1930s. In addition to Charles and Ray Eames, architect Eero Saarinen and artist Harry Bertoia, among others, studied or taught there. Detroit-based architect Minoru Yamasaki — who was a close friend of Eero’s and whose portfolio includes the McGregor Memorial Conference Center (1958), at Wayne State University, and the World Trade Center, in New York (1970–72) — was one of the many modernists who came within its orbit, and Florence Schust, an early graduate, went on to change the look of the American office as cofounder (with her eventual spouse, Hans Knoll) of Knoll Associates.

“Surprisingly, the museum had not done a survey exhibition of mid-century modernism in many decades, even though Cranbrook is often referred to as the birthplace of the movement,” says Cranbrook Art Museum director Andrew Satake Blauvelt, who cocurated the current show with the institution’s MillerKnoll curatorial fellow, Bridget Bartal.

In the past several years, the museum has expanded its holdings to include pieces by individuals from underrepresented communities, so while acknowledging all the marquee names, the show casts a wide net, encompassing the work of less well-known creatives. These include Joel Robinson, the only Black designer featured in MoMA’s “Good Design” exhibitions, which ran from 1950 to 1955; Ray Komai, who made an impression with a single-piece, molded-plywood side chair before opting to pursue graphic design; and Lucia DeRespinis, one of only three women in her class when she graduated from Pratt Institute in 1952, who spent nine years at George Nelson Associates before taking on clients of her own and returning to teach at her alma mater.

Among the many compelling facets of the exhibition is the light it throws on designing couples and independent women. “Take, for example, Estelle and Erwine Laverne,” says Bartal. “In 1938, they cofounded their business, Laverne Originals, for which they designed fabrics, wallpapers, furniture, accessories and interiors. Because the Lavernes ran their small business by themselves, it was not as easy for Estelle to be taken out of the equation. For that reason, Erwine’s name is almost never mentioned without Estelle’s — they were very much marketed as a design couple. It’s worth noting, too, that although some women found commercial success through professional partnerships with their husbands, pioneering women — Eva Zeisel and Greta Magnusson-Grossman, among others — garnered astounding successes in the fields of industrial design and architecture.”

George Matsumoto and George Nakashima were among the West Coast Nisei (American-born children of Japanese immigrants) interned under Executive Order 9066 following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and the curators have made a point of touching on that specific history. “The overwhelming successes of Japanese American architects and designers in this era was a particularly fascinating thread throughout our project,” says Bartal. “After their release from the internment camps, they returned to rebuild their lives and reshape their fields. Architect and innovator Shoji Sadao, for example, began working with Isamu Noguchi, who was well connected to [graphic designer] Tomoko Miho and other successful Japanese Americans. I like to call this an ‘in-group of outsiders,’ a tight-knit community who were rooting for one another, actively helping each other find work.”

“Everything Connects” explores a range of themes, from biomorphism to the marketing of modern design, all of which are fully articulated in a companion volume published by Phaidon that features essays by dozens of historians. The breadth of the movement is manifest in the spectrum of material on view, from immediately recognizable classics — think George Nelson’s Marshmallow sofa (1956) and Warren Platner’s lounge chair and ottoman (1966) — to more under-the-radar products, such as Bill Lam’s fiberglass-and-oak Lite table (early 1950s) and the brightly dynamic textile designs of Gere Kavanaugh and Marianne Strengell.

An image from a ca. 1948 Dunbar catalogue depicts Edward Wormley’s Listen-to-Me chaise longue. Photo courtesy of the Edward J Wormley Papers, The New School Archives and Special Collection, The New School, New York, NY

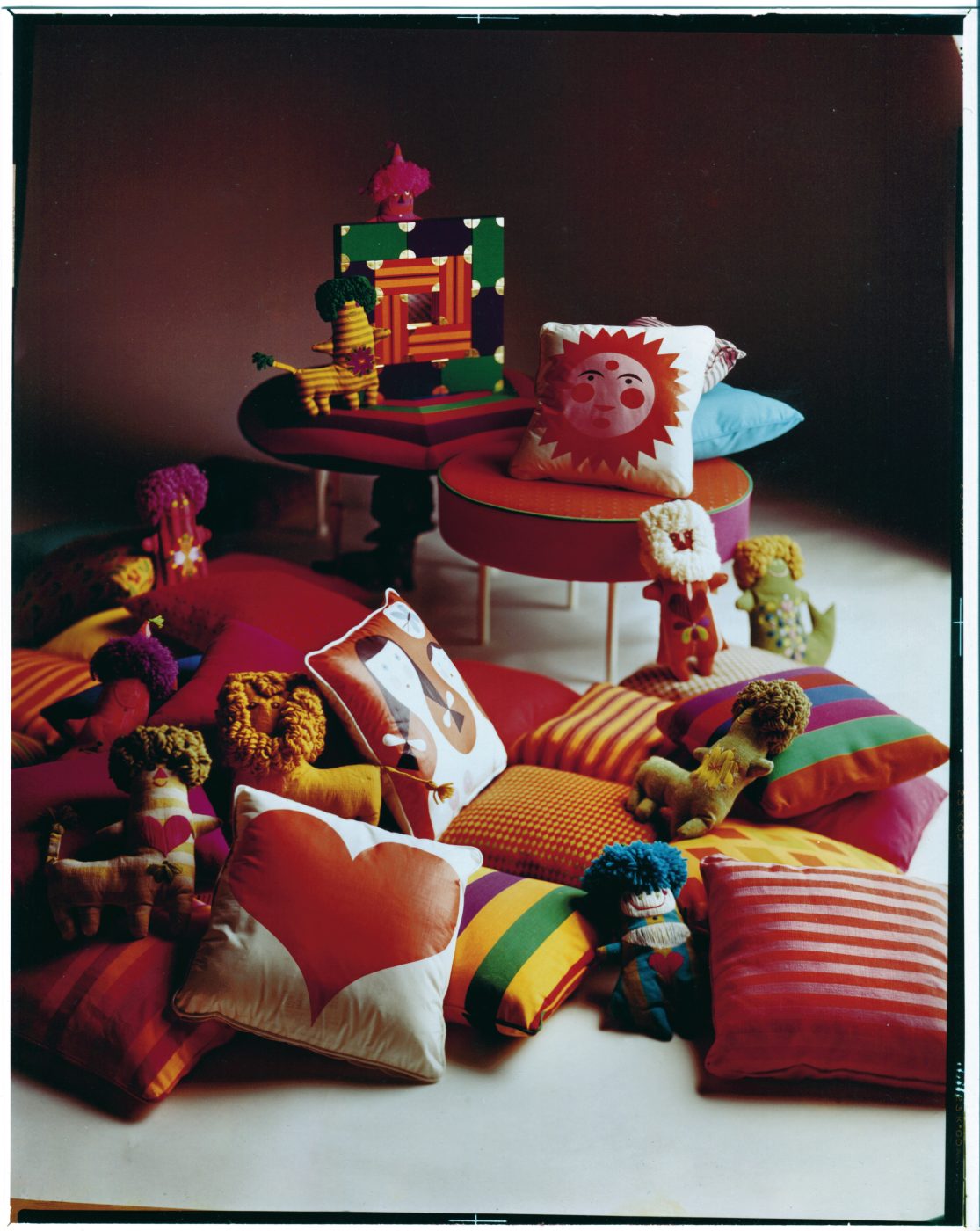

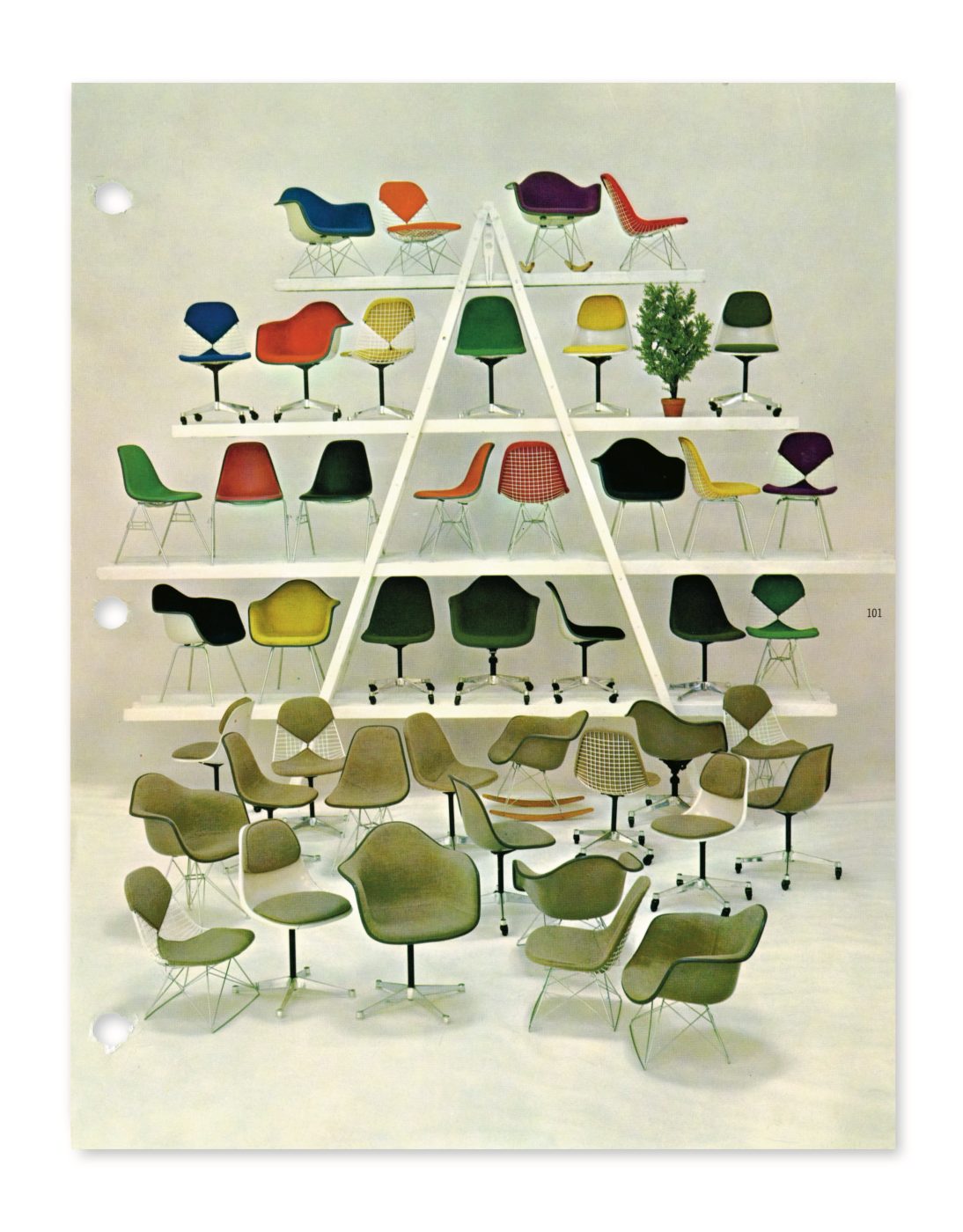

The exhibition narrative is engagingly articulated, as well, through documents that helped establish the aesthetic in the marketplace and in the public’s perception: a promotional image for Herman Miller featuring dolls designed by Marilyn Neuhart and furniture and pillows designed by Alexander Girard, a booklet from the IBM Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair and a shot from a sales catalogue evocative of an Irving Penn still life promoting a hot-pink Edward Wormley Listen-to-Me chaise longue.

“There are so many objects that really spoke to us in assembling our checklist for the show, each for a different reason,” says Blauvelt. “Take, for instance, Harry Bertoia’s Asymmetric chaise longue. We are showing one of two prototypes from 1951, as the experimental and expensive design didn’t make it into production until the 2000s. Bertoia’s contributions to design through the use of metal wire are completely in sync with his work as a sculptor and his knowledge of metalsmithing, a focus of his work at Cranbrook.”

For consumers who took to it in its early years, and for those who rediscovered it beginning in the 1980s, the exuberance and innovation of mid-century design represented a lifestyle and a sensibility, an appreciation for how everyday objects define everyday life. That sense of totality, of seamless integration and across-the-board experimentation was, and remains, central to its appeal. Those newly intrigued by the style may not catch all that in a beautifully Instagrammed Womb chair, but it’s there.