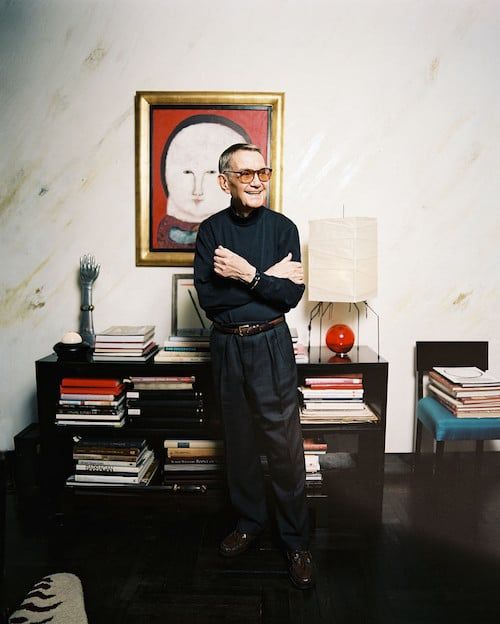

Albert Hadley in his apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Photo by Patrick Cline via Lonny

The iconic Albert Livingston Hadley Jr. (1920–2012) was an interior designer of immense talent and rare distinction. Although ultimately considered the dean of American interior designers by many in the field, his name and much of his legacy will forever be linked to an even-more celebrated decorator: the Yankee patrician Sister Parish.

In talent and in temperament, Parish couldn’t have been more different than that of this genial, ever-inquisitive and modern-minded Southerner. Yet together, they were like “two flints striking against each other and starting a fire,” writes Adam Lewis in his 2005 biography Albert Hadley: The Story of America’s Preeminent Interior Designer.

Born in Springfield, Tennessee, Hadley’s father owned an agricultural equipment business. The family moved frequently. His mother, Elizabeth, busied herself decorating their new houses, and her son took an interest in her efforts. Captivated by home decorating and fashion magazines, along with Hollywood movies, Hadley knew by his early teens that his destiny was in New York. He attended a local college for two years, but eager to get on with his future, he soon apprenticed himself to A. Herbert Rogers, one of nearby Nashville’s leading decorators. A couple of years later, he was drafted into the army, and when he returned after the end of the World War II he took advantage of the G.I. Bill to finally move to New York and attend Parsons School of Design.

At Parsons, the school’s president, the urbane and supremely gifted designer Van Day Truex, took a shine to the young Hadley and offered him a teaching job after he graduated in 1949. The six years he spent as a professor at Parsons expanded and deepened his knowledge of design history, providing him with a vast reservoir of erudition, which enabled him to work fluidly in Georgian, Victorian and modern styles when he eventually practiced his trade. In 1956, he left the school to work for Eleanor Brown, the formidable founder of McMillen, Inc., then the leading decorating firm in the country. There, he refined his talent for rationalizing floor plans and drawing curtain treatments.

He “always thought out rooms intellectually,” recalls Bunny Williams in Parish-Hadley: Tree of Life, a memoir about the firm. Williams, who was mentored by him when she worked at the firm, coedited the book with Brian McCarthy, a fellow alum. “His incredible working drawings were pretty close to how the projects were carried out.” By contrast, she writes, Sister Parish worked by instinct and intuition.

In fact, it was because Parish couldn’t draw and had no real sense for how to design the bones of a room that she found herself in need of someone with drafting skills as her projects became more complex in the late 1950s. For a recommendation of someone who might fit the bill, she turned to Truex, by then the design director at Tiffany & Co. He thought of Hadley. Legend has it that Hadley was summoned to Parish’s grand Fifth Avenue apartment and was immediately flustered when she opened the door herself in her stocking feet, and her Pekingese came charging at him. Parish, he was soon to learn, delighted in discomfiting people, which is why she then asked the very proper Southerner to zip up the back of her still partially open cocktail dress. Years later, the interior designer Tom Britt quipped to Adam Lewis that that zip caused “the biggest explosion in 20th-century decorating.”

The Hadley-designed apartment of Seagram’s chairman Edgar Bronfman and his wife. Photo by Edward Lee Cave via Michael Gross

At McMillen, Hadley had been involved in design projects for some of America’s grandest families, but when he went to work for “Sis,” he was immediately recruited for the most prestigious one yet: decorating the family quarters of the Kennedy White House. Ever modest, Hadley insisted his sole role had been sketching the curtains. But he did admit to having a more vital contribution to another early project: the sprawling prewar apartment at 740 Park Avenue of Seagram’s chairman Edgar Bronfman and his wife.

The couple had approved the designs for a typical Parish apartment, full of chintz and fine antiques, before they went on a vacation in Mexico. But after they left, they sent a telegram: “Stop all work. We want a floating apartment.” Parish had no clue what they meant and was horrified when Hadley explained that the Bronfmans wanted something more open and modern. However, the prospect thrilled him. Hadley replaced one of the drawing room walls with glass and installed a grand travertine staircase. Having regained her composure, no doubt with Hadley’s coaxing, Parish held up her end of the decorating project by selecting a collection of important 18th-century chairs to play counterpoint to the flowing open spaces and limestone stairs he designed.

The finished project, still relatively traditional but refreshingly spare, anticipated the transitional style so popular today. This bracing new vision demonstrated the decorative power that this yin-and-yang pair would wield in the years to come.

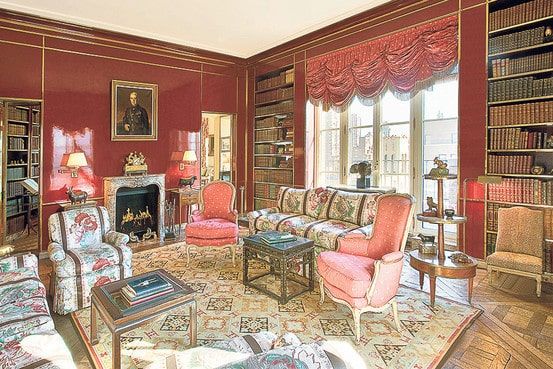

The library of Brooke Astor’s Hadley-designed Manhattan apartment featured lacquered oxblood walls with brass trim. Photo by Stribling & Associates via the Wall Street Journal

In the 1970s, Hadley made waves when he designed the Park Avenue apartment of New York’s grandest grand dame, Brooke Astor. The residence, while classic, felt fresh and airy. Most striking was the chic library — an important room for the Lady Bountiful of the New York Public Library. He had the bookcases and walls painted with 10 layers of oxblood enamel and trimmed with brass. The effect was utterly glamorous, yet with its overstuffed chintz sofas and armchairs, thoroughly inviting.

Annette de la Renta, who employed the firm on several family projects, admired how easily Hadley moved between decorating styles and project scales, pointedly observing that the designer “was never dismissive of taste that wasn’t his own.” That was the opposite of Parish, who could be scathing in her judgments. Taste was important to her, as was social background. She was famous for turning down potential clients, especially the parvenu, whose credentials didn’t meet her standards.

In light of this, it is extraordinary that she and Hadley had such a remarkably creative and fairly copacetic partnership that lasted more than 30 years. Because for Hadley, decorating was a rather generous pursuit. Acknowledging that he’d designed many much-publicized homes for the likes of Astor, Babe Paley and Happy Rockefeller, he told one interviewer, “[N]ames are not the point. It’s what you can achieve for the simplest person. Glamour is part of it, but glamour is not the essence. Design is about discipline and reality, not about fantasy beyond reality.”

Gracious and kind, and an eager mentor, Hadley influenced a legion of young designers with his brilliant eye and his gift for synthesizing classic and contemporary styles. As legendary as Sister Parish may be, it is Hadley’s decorative vision that most truly lives on.