Portrait of Dorothy Draper.

The life of Dorothy Draper (1889–1969) reads like an old Hollywood movie. Consider the plot line: a free-spirited, impossibly beautiful, and larger than life — six foot tall, in fact — American blue blood, is abandoned by her husband when her children are small, a week after the 1929 stock market crash, yet goes on to forge a career as an interior decorator with a singularly flamboyant style and builds her name into an internationally recognized, money-making brand, designing everything from five-star hotel lobbies to cosmetics packaging. Only in the movies, right? But it’s true.

By the end of the 1930s, Dorothy Draper was a household name, and would be one until she sold her company in 1960. While her namesake firm still exists, she and her accomplishments have largely faded into history. Yet her distinctive Regency Moderne style — vivid color, audacious floral prints, outrageously wide stripes, oversized baroque plasterwork, and other playful twists of scale and material — which is also called Hollywood Regency, influenced designers as disparate as Miles Redd and Frank Gehry, Philippe Starck and Kelly Wearstler.

Lobby of the Greenbrier Hotel.

Born into a life of privilege, Dorothy grew up in Tuxedo Park, New York, a gated rustic enclave favored as a weekend retreat by New York’s social elite, where residents lived in “cottage” mansions and the gamekeeper staff were kitted out in tweed knickers and Tyrolean hats. She roamed free, had little schooling, and was so enchantingly bold and charismatic that her parents nicknamed her “Star.”

In 1912, when she was 23, Dorothy married George Draper, a doctor and childhood chum of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. (Her husband became a specialist in treating polio and is credited for helping FDR recover as best he could from the illness.) The newlyweds settled into a brownstone on Manhattan’s East 64th Street, around the corner from Franklin and his wife Eleanor, who was also Dorothy’s cousin and a close childhood friend.

While the neighborhood was tony, the Draper house was gloomy with a sunless backyard. Eager to entertain and live with light, greenery and flowers, DD — as the married Dorothy would come to be known — decided to do something about it. She extended the brownstone’s ground floor to encompass the entire yard, turning it into a grand party room that could accommodate a couple of hundred guests, and put a garden on the sunny roof of the addition. It was an architectural solution no one had yet thought to do. Called the “Upside Down House,” it was adored by her friends who began asking for help with their own houses.

And so began her amateur hobby as a decorator. Undeterred by the old rules of Victorian decorating, DD would, as she later described, “jumble periods cheerfully,” lacquer old furniture (she despised wood) and saw down the legs of heirloom pieces if a lower height better suited her. The effect was all. And her client friends loved what came to be known as “the Draper touch.” Within a decade or so, in 1925, she turned this knack for interior design (and her voluminous address book of architects, contractors and craftsmen) into a business she could run from home called the Architectural Clearing House, later renamed Dorothy Draper Co.

In 1928, DD’s friend, the real estate mogul Douglas Elliman, got her a job decorating the lobby of a new residential hotel, called the Carlyle. The decor she conceived was splashy yet elegant, with grandly scaled mirrors and chandeliers, marble columns and classical busts, and a big, jazzy checkerboard floor of black and white marble. Yet DD’s moment of triumph came at a time of disaster: her husband left her for another woman and the hotel went bust as a result of the stock market crash.

The lobby of the Carlyle Hotel in 1937.

But as was typical with DD, bad luck soon turned to good when the wealthy businessman Henry Phipps — a business partner of Andrew Carnegie — commissioned her to renovate a row of Sutton Place apartment buildings that no one wanted to rent. Taking inspiration from the smart-looking townhouses of Dublin, she painted the brick buildings black with white windowsills and doors in brilliant colors, and wrapped the hallways with floral wallpaper and carpeting to enliven the interior spaces. What had been drab was now chic. Soon, the apartments were all rented for four times their original fee. And in compensation, for reduced rent, DD and her youngest daughter moved into a one bedroom, the walls and ceiling of which she painted sky blue.

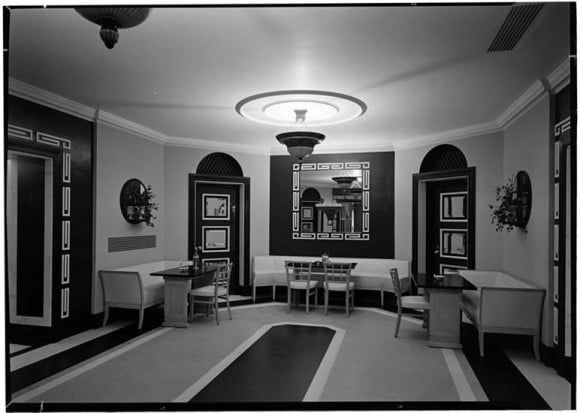

The Deco dining room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Meantime, the new owner of the Carlyle hired her to decorate the rest of the public spaces, and they were such a success that hospitality work became an important percentage of her business. Among her commissions were the majestic Deco dining room at the Metropolitan Museum — famously called the Dorotheum in her honor — Hampshire House in New York and Boston, the Drake Hotel’s Camellia House restaurant in Chicago, the Fairmont and Mark Hopkins hotels in San Francisco, and the sprawling Greenbrier Resort in West Virginia, which may be her masterpiece.

The enfilade leading to the Victorian Writing Room at the Greenbrier.

Despite her growing list of commissions in the 1930s, DD also managed to find time to write a design manual for housewives, which she titled Decorating is Fun! Published in 1939, it was also a clever self-help book for insecure homemakers. In the opening pages she tells her readers that the first rule of decorating is “COURAGE,” along with color, balance, smart accessories and comfort. “If it looks right, it is right!” was the maxim she shared. Her advice was wise and proto-feminist: “Your home is the backdrop of your life, whether it is a palace or a one-room apartment, it should honestly be your own — an expression of your personality.”

In the 1950s, DD explored new design frontiers. She also created airplane interiors for Convair, auto interiors for Packard and Chrysler — including a pink polka-dotted truck — and cosmetics packaging for Dorothy Gray. All the while, she was also designing theaters, department stores, corporate offices and home interiors of fellow bluebloods along with parvenus.

Decorating started as a lark for Dorothy Draper, but became a means of self-empowerment and a path to fame and fortune. And along the way she forever changed American style. You might say that if her friends the Roosevelts gave the country a New Deal, she gave it a New Look: one that was buoyant and original, with just a touch of swagger. You can’t get more Hollywood than that.