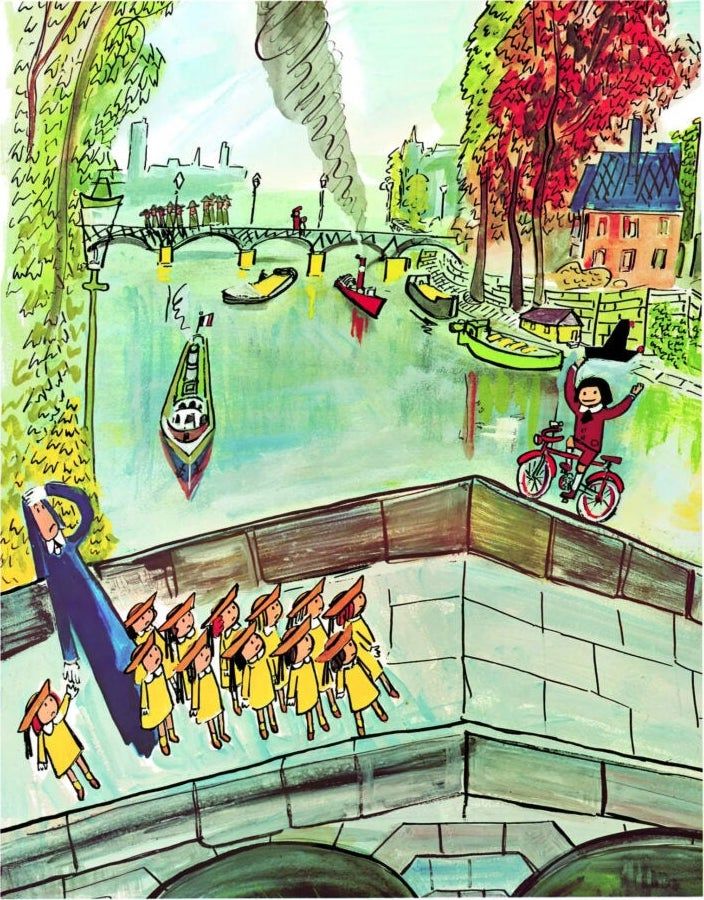

When Ludwig Bemelmans drew the charming illustrations for his classic 1939 children’s book Madeline, he made the setting — Paris — a main character, second only to the little girl of the title.

Each day, Madeline and her 11 boarding-school pals venture out with their nun caretaker, Miss Clavel, “at half past nine / in two straight lines / in rain / or shine.”

As they trundle through the city, we glimpse behind them the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, the Place Vendôme, the Tuileries Garden, Notre-Dame and other Paris landmarks.

A similar obsession with place comes through in Bemelmans’s oil-on-board painting of Coney Island at night, from the 1940s. In it, the artist enthusiastically depicts the Brooklyn seaside destination’s Cyclone roller coaster, Wonder Wheel ferris wheel, Parachute Jump ride and boardwalk — nostalgic attractions that still stand on Coney Island today.

In fact, given that the dozens of peachy ovals representing heads have no faces, we sense that the place itself is the real subject of the painting.

The marks on the board appear unbound and impressionistic, making the frenetic motions of the rides and attendees palpable. “I sketch with facility and speed,” Bemelmans once wrote. “The drawing has to sit on the paper as if you smacked a spoon of whipped cream on a plate.”

And while the oil painting surely took him longer to assemble than a sundae, we can sense the swiftness of his brushwork in the loose curves of the Cyclone tracks and the dizzying spin of the Tilt-A-Whirl.

Surrounding the whole scene is a silvery wooden frame with a deep linear grain. “When the artist’s grandson saw the painting, he immediately remarked about the frame, as he knew the style from many of his grandfather’s works,” says Keith Sherman, cofounder of Helicline Fine Art, which represents the piece.

Ludwig Bemelmans was born in Merano, Austria-Hungary (today part of Italy), in 1898 to a Belgian painter-hotelier father and a German mother. As a teen, he apprenticed in the hotel restaurant of his uncle, who soon shipped Ludwig to the United States because of the young fellow’s incorrigibility.

There, Bemelmans joined the U.S. Army and after a string of hotel and restaurant jobs, worked his way up from busboy to banquet manager at New York’s Ritz-Carlton, where he secretly drew pictures in newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst’s unoccupied suite.

Bemelmans dreamed of being a cartoonist — he even had a comic strip called “Count Bric-a-Brac” that ran for six months in New York World magazine in 1926 — until May Massee, an acquaintance who was an editor at Viking Press, convinced him to write and illustrate children’s books.

Throughout the 1930s, he published a string of books for kids, including the Newbery Honor–winning The Golden Basket (1936), which took place in Belgium, where he’d honeymooned with his wife Madeleine “Mimi” Freund. The story introduced, in passing, a dozen young boarding-school girls on a stroll with their nun caretaker. The author would later expand on those characters in Madeline.

Beyond authoring children’s books, Bemelmans, a world traveler and bon vivant, decorated interiors and theater sets; wrote novels, screenplays and journalism; illustrated magazine covers, advertisements and signs; mounted gallery shows; and painted numerous whimsical murals, including, most famously, at Bemelmans Bar (named for him since its opening) of the Carlyle Hotel on Manhattan’s upper East Side.

“Clearly, in the late 1940s, Bemelmans was in a New York City frame of mind,” Sherman says. “The artist painted the interior of the bar with murals depicting the seasons in Central Park, with Madeline. The bar opened in 1947, about the same year that the Coney Island painting was created and a year before Bemelmans’s July 3, 1948, New Yorker magazine cover depicting Coney Island — with an astonishingly similar rendering of the Cyclone roller coaster — was published.”

This was an era of great buoyancy and growing prosperity in the U.S. The German and Japanese empires had been defeated, and soldiers were swarming back home to find peacetime jobs, have fun and make babies.

Coney Island offered free admission and discounts to the military throughout the 1940s. And “the expansion of the New York City subway system later in the ’40s made Coney Island more accessible than ever, turning it into a true People’s Playground,” says Sherman, mentioning the area’s longtime nickname.

“It was a moment of optimism,” he adds, “and this painting exudes the joy of escape, the thrill of a roller coaster and a day at the beach.”