The pool and courtyard of the Waterside Hotel in North Miami Beach. Photos by Kirk Paskal, unless otherwise noted

Miami Beach’s coastline is coveted by the international jet set for its crystal blue water, soft white sand, abundant sunshine, diverse culture and, perhaps most famously, its Art Deco architecture. And while Deco absolutely defines the South Beach aesthetic, all Easter-egg hues and cheerfully stylized facades, there’s the equally vibrant North Beach that’s defined by another architectural style: Miami Modern, or MiMo for short, is a movement that recently celebrated a big win for its own historical significance.

On January 17, 2018, Miami Beach’s city hall commission unanimously voted to grant more than 250 modernist buildings in North Beach special protections against demolition. As Kirk Paskal, board member on the Miami Beach Historic Preservation Board, explains, these historic districts “seek to protect and optimize significant portions of areas that were previously added to the National Register of Historic Places” but received no protections from demolition at the time.

“Community advocates, allies, and MiMo enthusiasts for many years have been actively advocating to safeguard and promote the character and allure that distinguishes the North Beach MiMo districts. With 271 contributing historic buildings — and an additional 68 contributing historic buildings that are part of a current expansion of the North Shore Historic District to include the Tatum Waterway — this occasion marks the largest expansion of local historic protections in North Beach and the largest in the City of Miami Beach since 1990,” Paskal explains.

Miami Modern architecture was born out of a “regional response to the Bauhaus movement during the post–World War II building boom in Miami Beach,” says Franziska Medina, a MiMo tour guide with the Miami Design Preservation League, “when young architects, eager to try new things, shifted away from the Bauhaus ‘less is more’ aesthetic by embellishing their buildings with curved surfaces, bright colors, walls with circular, rectangular and lace-pattern cutouts and boomerang angles.”

Additionally, Medina notes that MiMo is characterized by “pylons, marine imagery, sweeping curves, catwalks, open courts, porte-cochères, brise-soleil and delta wings.” More natural and traditional imagery often found on a MiMo building includes “contrasting textures of stone, brick, tile and patterned stucco, layered brick, stone and exposed brick (a Frank Lloyd Wright influence), ornamental ironwork and decorative railings rendered in modern geometric designs.”

It’s a seemingly dichotomous style that was nonetheless successful for its “glamorous, dramatic, fun and exuberant” architectural themes, Paskal says, bringing “innovative forms that incorporating greater functionality” to the North Beach aesthetic. Here, Paskal tells all about some of the most iconic examples of MiMo architecture.

Hirbess Apartments by Manfred M. Ungaro, 1952

“This is a poster MiMo building with the exposed brick dramatically growing out of the building. The twin buildings have a shared interior court, catwalks, repeated masonry columns, etched eaves, built-in planters and pronounced boxed windows. North Beach’s many mirror-matched buildings are often joined by dramatic proscenium facades, creating grand entrances into open courtyards that are not only glamorous, but elevate the quality of life and connection to the outdoors. This structure is favored by visiting architects from all over the world.”

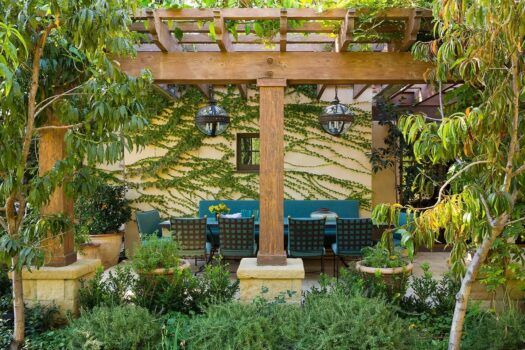

Waterside Hotel by Robert M. Nordin, 1957

Photo by Carolina Di Filippo

“The joined gabled roof, also known as the ‘chalet style,’ provides a grand entrance feature for the inner courtyard pool area and surrounding catwalk configuration. MiMo brought a breath of fresh air, new excitement, innovation and joy to residents and visitors seeking a tropical lifestyle,” Paskal explains.

“The national optimism that followed the end of the Second World War is mirrored in the vibrant colors and forms that celebrate life and prosperity. This movement in North Beach was further fueled by the economic recovery and building boom that created housing for new residents and lodging for visitors as Miami Beach entered the golden era as America’s riviera.”

Bayside Condos by B. Robert Swartburg, 1952

“Bayside condo has the appeal of a seaside resort by one of the most celebrated Miami Beach architects — Swartburg also designed the Delano on South Beach — with a dramatic entrance of intersecting planes, screen-block boxed windows and angled beanpoles. The atomic age gave rise to a spirit of futurism, modernity and national pride,” according to Paskal.

“The arrival of air conditioning afforded further opportunities while nurturing a year-round economy in Miami Beach. In North Beach, architects experimented by pushing innovation in materials and new design. Many value North Beach for its vintage American beach town charm and lower intensity and scale, which affords greater access to natural light and open views.”

Union Planters Bank by Frances R. Hoffman, 1958

“Union Planters Bank combines modernist and classical forms. The facade of breeze blocks, consisting of concrete circles, forms a modern-day frieze, while the protruding pillars divide the facade into the classical ideal of six bays. The screen block applies a sense of lightness and permeability to the whole building,” Paskal says.

“In contrast to other areas of Miami Beach, where development activity has progressed with greater pressure and intensity, North Beach has grown in a more gradual and organic way, retaining much of its diversity and small-town feel. The North Beach community is very engaged in safeguarding and optimizing not only its wealth of revered mid-century modern architecture but also the diversity and livability that make this area of Miami Beach uniquely alluring.”

Temple Menorah, by Gilbert Fein, 1951, and Morris Lapidus, 1963

“A landmark building, the Temple Menorah is an impressive tower which is covered on all sides with ‘cheesehole’ cutouts, a Morris Lapidus trademark. The base of the tower is anchored to the main facade by an open staircase, providing access to the upper floors. The temple has a dual image. On the main facade are the tablet-shaped arches with stained glass and on the north facade are vertical masonry louvres from the first to second floor.”

The Drake Villas by Donald Smith and Irvin Korach, 1948

As referenced in the National Register Nomination Report, “This is the North Shore’s most ambitious project: the Drake Villas along Tatum Waterway Drive. It was designed by architects Donald Smith and Irvin Korach in 1948, who aimed to create a campus of more than 23 buildings spread out across more than 2,000 linear feet of water frontage. Thirteen of the buildings were constructed. Envisioned by developer Jacob Freidus, the buildings were grouped to frame patios and courts, pool and cabana areas, tennis courts and other recreation areas.

“The Drake ensemble was based on a building module that rejected Miami’s vernacular masonry and wood construction, employing concrete instead for both walls and floor slabs. Even the stair railings and porch balustrades are constructed of cast concrete. Some are connected on the second story by a concrete bridge with pierced concrete-block walls. The bridge shelters the walkway below that provides access between the buildings.”