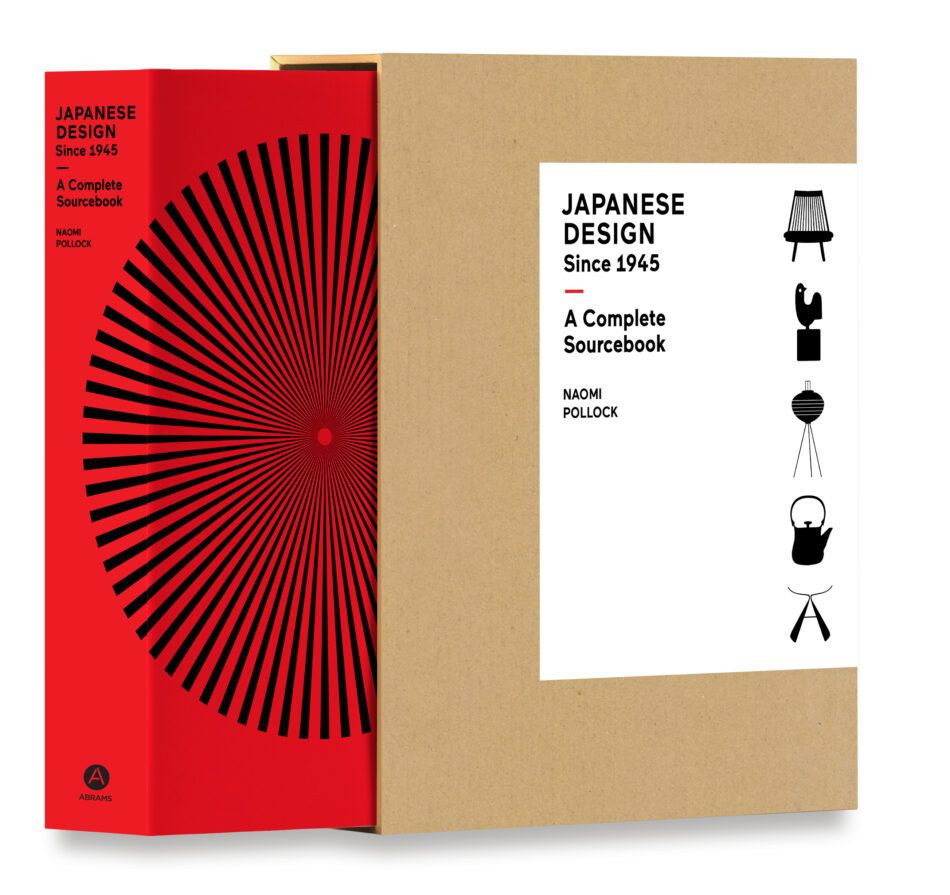

“In Japan, design is as much something that is done with the hand as the eye,” says American architect and design writer Naomi Pollock. A resident of Tokyo for 30 years and the author of several books on Japanese design and architecture, Pollock has now published her most comprehensive work on the subject: Japanese Design Since 1945: A Complete Sourcebook (Abrams).

“It became apparent to me that there was a need for a book that looked at Japanese design as a whole,” explains Pollock, noting that the country has no dedicated design museum or central archive. “It’s truly mind-boggling. So, I felt compelled to do my best to create something of an archive between two covers and bring all of these different aspects of Japanese design together in one place.”

Organized thematically, the thick, beautifully designed tome includes more than 70 creator profiles, thoughtful essays from Pollock and other experts, engaging takes on iconic pieces and images of hundreds of objects — furnishings, tableware, textiles, graphics, packaging, appliances and household goods — created by Japan’s leading designers from the postwar period to today.

The book traces Japan’s path to contemporary design, taking a deep dive into the concepts underlying the creations, which are rooted in the country’s craft tradition. “That’s evident in the phenomenal attention to detail, the exquisite way that things are made,” Pollock says. “These objects feel good in the hand, they feel good to sit in. They just relate well to the body because they’ve been designed with the body as one of the leading tools.”

They’re also exceptional for their high quality. Japanese designers, according to Pollock, have largely resisted the pressure felt by their counterparts around the world to enable cheaper and faster production by cutting corners. “Japan is stubbornly entrenched in ‘No, we’re not going to do that,’ ” she states. “And that comes through in this incredible quality. The objects have been designed and made to last and last and in some cases actually improve with age.”

Here we look at 10 objects and the designers behind them.

Isamu Noguchi Akari Light Sculpture

Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi conceived his first Akari light sculpture in 1951, following a visit to a historic lantern maker in Japan’s Gifu Prefecture. Constructed from washi paper with bamboo supports, the warm lights are produced by a small Japanese factory that has been using the same techniques for a long, long time.

“He took something that was very traditional and made it extremely contemporary,” says Pollock. “They are as much artistic objects — even though they’re mass produced — as they are light-giving devices.”

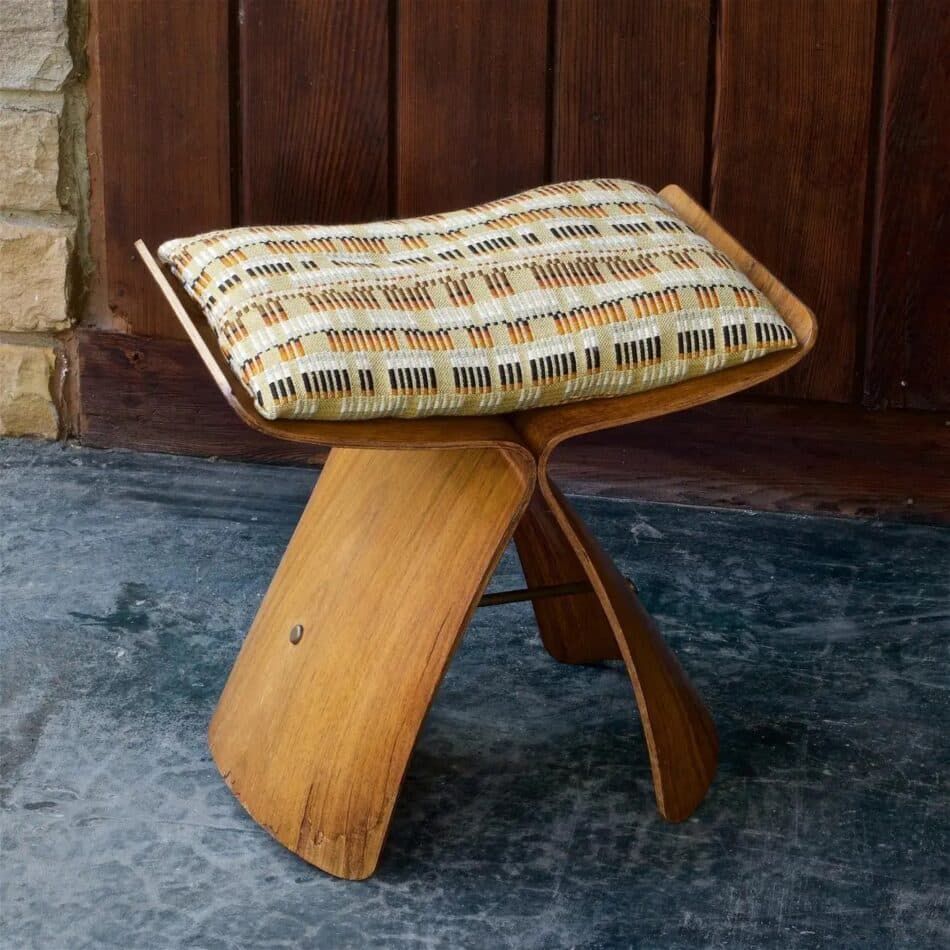

Sori Yanagi Butterfly Stool

The celebrated Butterfly stool, made from two curved plywood plates, is an exquisite example of Sori Yanagi’s blending of new technologies with traditional Japanese craft. The son of Soetsu Yanagi, the founder of Japan’s Mingei folk art movement, the designer conceived this chair after meeting Charles and Ray Eames in the U.S. and encountering their bentwood work.

He brought the idea back home, where he and an engineer at furniture manufacturer Tendo Mokko “developed this new technique for molding,” says Pollock. “And they gave it this elegant, timeless form. It doesn’t ever go out of style.” The popular stool was first released in the 1950s and has been in production ever since.

Isamu Kenmochi Coffee Table

A pioneer in Japanese interior design (at the end of World War II, the discipline didn’t really exist in the country), Isamu Kenmochi introduced an aesthetic he called Japanese modern, which updated time-honored forms and types.

This low, zataku-style coffee table, which came out in the 1960s, “is a very traditional style of table that would be used in a tatami room,” says Pollock. “It’s a very user-friendly, flexible, multifunctional table. But in a Western context, it also happens to be a reasonable shape and size for a coffee table. So, it has this great flexibility of being sort of bicultural.”

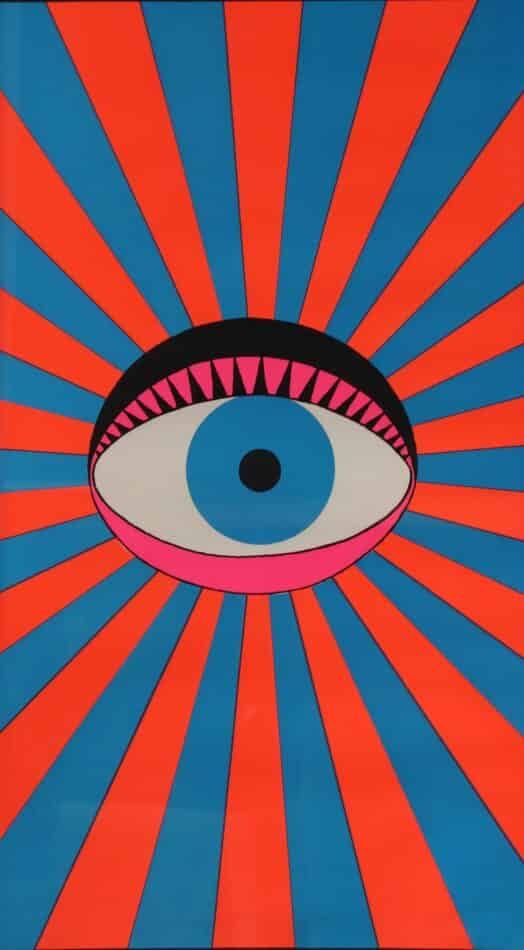

Tadanori Yokoo “Word Image” Poster

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Tadanori Yokoo was an internationally recognized graphic designer, whose work drew on Surrealism, American Pop art and Japanese culture. This unexpected mashup of influences came together seamlessly in designs such as his 1968 poster for the “Word and Image” exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. “Because he didn’t have as much formal training, he had this freeness about him that yielded work of quite remarkable intrigue,” says Pollock.

In the 1980s, he made an abrupt change. As Pollock writes in the book, “He gave up design in favor of painting and never looked back.”

Shiro Kuramata Furniture in Irregular Forms Side 1 Cabinet

Shiro Kuramata is on the artistic end of the spectrum of Japanese design. “Some of his furnishings, you kind of look at them and think, ‘Gosh, is that even functional?’ Then, it’s sort of like, ‘Well, does that even matter? It’s such an incredibly interesting object,’ ” says Pollock, who explains that Kuramata’s pieces, like his wavy Side 1 cabinet, were inspired by dreams. “So when you look at this piece, it looks like something that would come out of a dreamscape more than a furniture showroom.”

First released in the 1970s, the radical chest of drawers is still being made by Capellini.

Toshiyuki Kita Wink Chair

“There’s a huge cross-fertilization in his work between Japan and Italy,” Pollock says of Toshiyuki Kita, who came on the scene in the 1970s and ’80s, when Italian design was gaining popularity in Japan, and who continues to maintain studios in Osaka and Milan. His Wink lounge chairs, designed in 1980, display the influences of both countries — the latter evident in the pieces’ playful shape and bright colors, the former in their versatility.

“The chair can be molded to fit pretty much any position someone would want to sit or lie in,” says Pollock. “That kind of flexibility is a very Japanese idea — wanting to be able to accommodate lots of different scenarios with one object. It’s got a very strong functionality, but also it’s a beautiful object. Even if no one is sitting in it, people enjoy looking at it.”

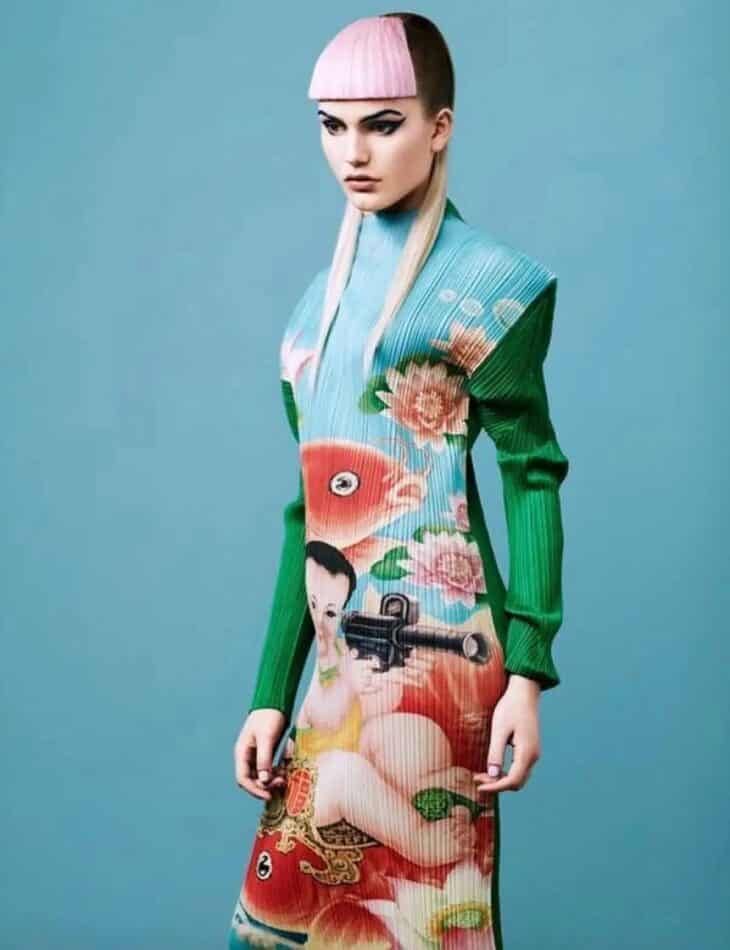

Issey Miyake Pleats Please Clothing Line

Issey Miyake approached fashion as a product designer with a mission. One such product is his Pleats Please line. Launched in 1993, the series features a vast array of pieces made from permanently pleated fabrics that can be used for garments of almost any shape, size, color and pattern.

This versatility aligns with the goal Miyake had when he went into fashion: to make clothing that is as universal and appealing as jeans and T-shirts.

Naoto Fukasawa Itka Table Lamp

Naoto Fukasawa has wielded enormous influence in his field (he is included among the book’s 13 Design Titans). But what Pollock appreciates most about him is the effortlessness of his products.

“Fukasawa designs things that just fit into your life,” she says. “He has a way of creating objects that’s very instinctual. So, you don’t have to think too hard about ‘How do you use this?’ ” His 1986 Itka lamp, with its simple beauty and subtle diffusion of light, is a case in point.

Oki Sato/Nendo Drop Bookshelf

Oki Sato, founder of the design firm Nendo, is one of Japan’s most prolific creators today — at every scale, from architecture on down. “I think he brings a lot of humor, a lot of whimsy to his work, and that makes it very relatable,” says Pollock. “That kind of draws people to the things he creates.”

A prime example of these alluring qualities is his 2011 Drop bookshelf, with a cube balanced delicately at an angle on its top.

Tokujin Yoshioka Smatrik Chair

One of the more spiritual creators in the book, Tokujin Yoshioka believes design is something that you feel. When Yoshioka designed the Smatrik chair, in 2018, “he wasn’t creating a chair, he was creating the experience of sitting,” says Pollock. “What is the experience of sitting going to be like in this chair? How does it cup the body? How does it support the back? What does it feel like when your hand touches the feet?”