Murray Moss visits his latest exhibition, “Inadmissible Evidence,” at Houston’s Hiram Butler.

Since closing his eponymous New York design store in 2012, Murray Moss has kept busy as a curator, collector and consultant to museum gift shops, which he is busy reinventing. Not long ago, his clients at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, introduced him to Joshua Pazda, the director of that city’s Hiram Butler Gallery, who expressed interest in one of Moss’s collections: a group of several hundred photographs that were shaded, painted, cropped and otherwise altered in preparation for publication by newspapers and magazines. The result is a show of 39 of the images, on view at Hiram Butler through January 7, under the title “Inadmissible Evidence: Annotated Press Photographs from the Collection of Murray Moss.”

The images, in many cases, display the ingenuity of publications in the pre-digital age. “If they needed to show a guy, and they had a picture of him from twenty years ago, rather than reshoot him, they would simply paint in gray hair, or remove the hair entirely,” says Moss. “They were very frugal. The images have been prepared, sometimes many times in multiple ways, for multiple uses.”

A quartet of photos in the show demonstrates how Moss left irregular gaps between images to signify missing information.

“These are workhorse photos,” Moss continues. “The normal criteria one would use to evaluate a photograph — including its condition — don’t apply here. These are deliberately mutilated. The question isn’t what it was, but what has it become. Does it have anything to offer us now?” In many cases, Moss says, the answer is yes. “They’re finished with their first life, and now we can appreciate them any way we wish. I look at them formalistically.”

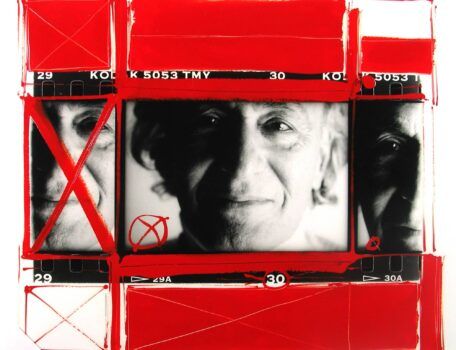

Moss compares the photographs to works by Robert Rauschenberg, who called his collages “combines.” “You take a photograph and marry it with painting and printmaking — it becomes another object,” he says. Moss hung the pieces at Hiram Butler “with large empty spaces between them, as a reminder that something is missing.”

Moss shares his knowledge with a gallerygoer.

What’s missing is the context. As a result, people make assumptions. “What I try to communicate with this exhibition is that information is subjective,” Moss says. “Each of us adds another layer of editing when we view these works. What do you want to see in it? What do you not want to see it? The viewer is a critical part of the artwork.”

But for all the meaning he attributes to the annotated photographs, Moss says, “I’m an object guy. I see these as being treated and mistreated and ending up as beautiful objects.”

Murray Moss Shares the Stories behind Some Key Images in the Show

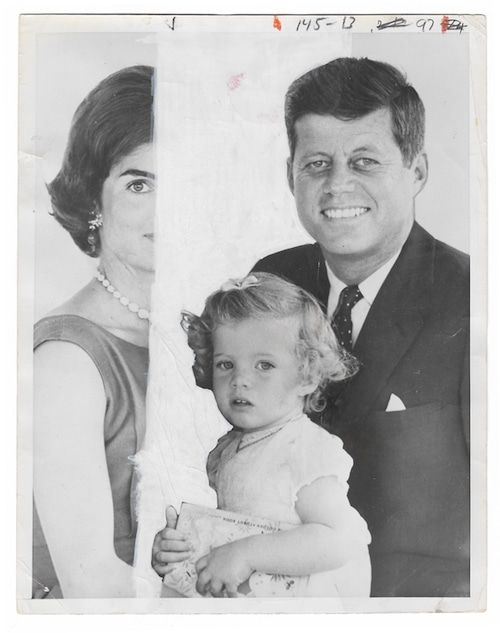

“That’s our royal family,” says Moss of the Kennedys. A magazine needed a photo of Jack and Caroline, which meant eliminating Jackie. “But the photo editors did it very respectfully, with the straightest line they could make freehand. They didn’t just put an X through her face. They created an amazing composition.” He adds: “People had agendas, and press photos were used to fulfill those agendas. They were altered, mutilated. There’s a kind of weird beauty and horror.”

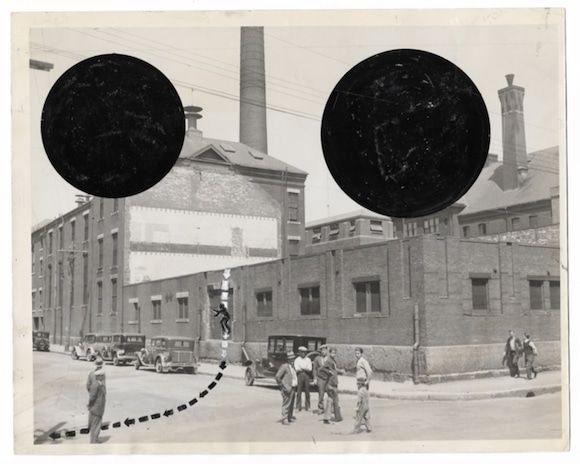

This photo, used to illustrate an article about a jailbreak, looks like a work by John Baldessari. The black dots are places where the editors expected to drop in text, says Moss (who has the benefit of reading notations on the backs of the photos). “The editors would say, ‘Let’s just slap on squares or circles where it doesn’t matter.’ ” They also added a representation of the escape route made of little arrows.

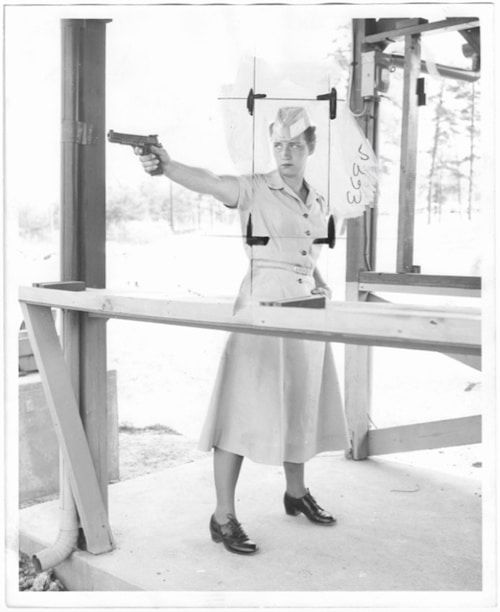

“This is a really good example of taking something out of context,” says Moss. “The concentration in her eye, the way she holds her lips, are based on the fact that she was aiming a weapon. But we’re not telling that part of the story. People seeing the published photo wouldn’t have known why she looked the way she did. It’s a blatant deception.”

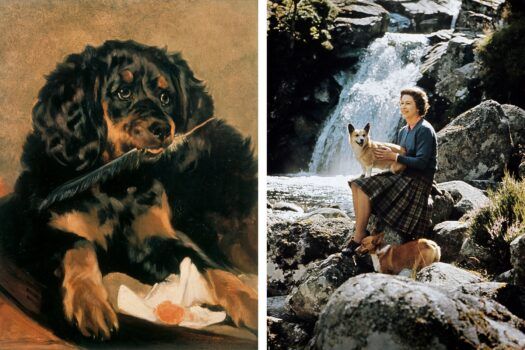

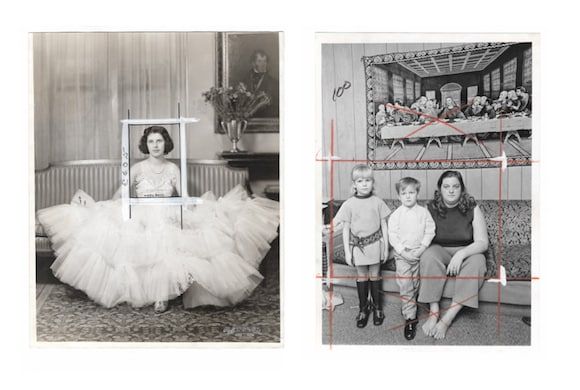

Left: Miss Ethel Hoffman, 1939, by Udel Brothers. Right: Mrs. Lila Lucas and Children, Left Penniless After Murder of Husband, 1972, by Weyman Swagger

“The whole point of that woman’s day was clearly the dress,” says Moss. “Her serenity, her pride, her complexion, they’re all about the dress. And they didn’t show the dress.” In the exhibition, Moss paired the woman’s photo with an image of a mother and her children, with a Last Supper rug behind them. “The story on the back is that her husband had been murdered and she was destitute. She’s barefoot, but her kids have shoes. But the editor didn’t want us to see that.”

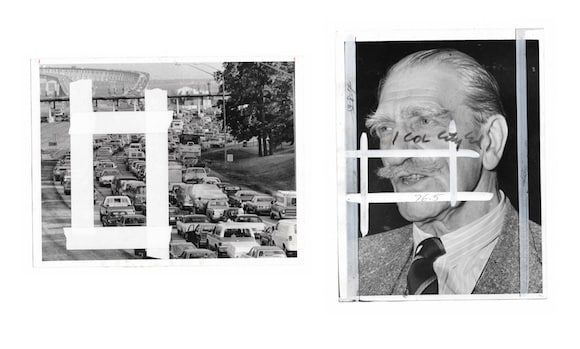

Left: Chesapeake Bay Bridge Traffic, 1982, by Walter McCardell. Right: Aubrey Smith; Ford’s Theatre, “Spring Again,” 1941, by an unknown photographer

“That’s an actor. They just stole his mouth, which is a very unattractive mouth. I don’t know why. But his eyes are as powerful and as communicative as his mouth is,” Moss says of the Aubrey Smith portrait on the right. For the show, he paired the photo with an image of a traffic jam, heavily cropped. “Somebody decided this is as much as you need,” Moss observes. “Not too much, not too little.”

About the author: Fred A. Bernstein studied architecture at Princeton University and writes about architecture and design for Introspective and many other publications.