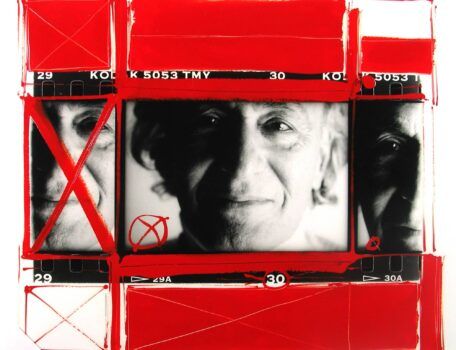

Over his four-decade career, photographer Jack Mitchell (1925–2013) chronicled the changing cultural landscape of mid- to late-20th-century America by capturing the greatest influencers and innovators in the performing and visual arts.

Mitchell, a master of lighting patterns in photography who had his first portrait published at the age of 15, organized more than 5,400 photographic sessions in his lifetime involving a list of sitters that is as astounding as it is long. A veritable roll call of heroes and idols, his studio guests include painters, dancers, actors, comedians, singers, composers, directors, writers, impresarios and anyone else who helped shape the zeitgeist.

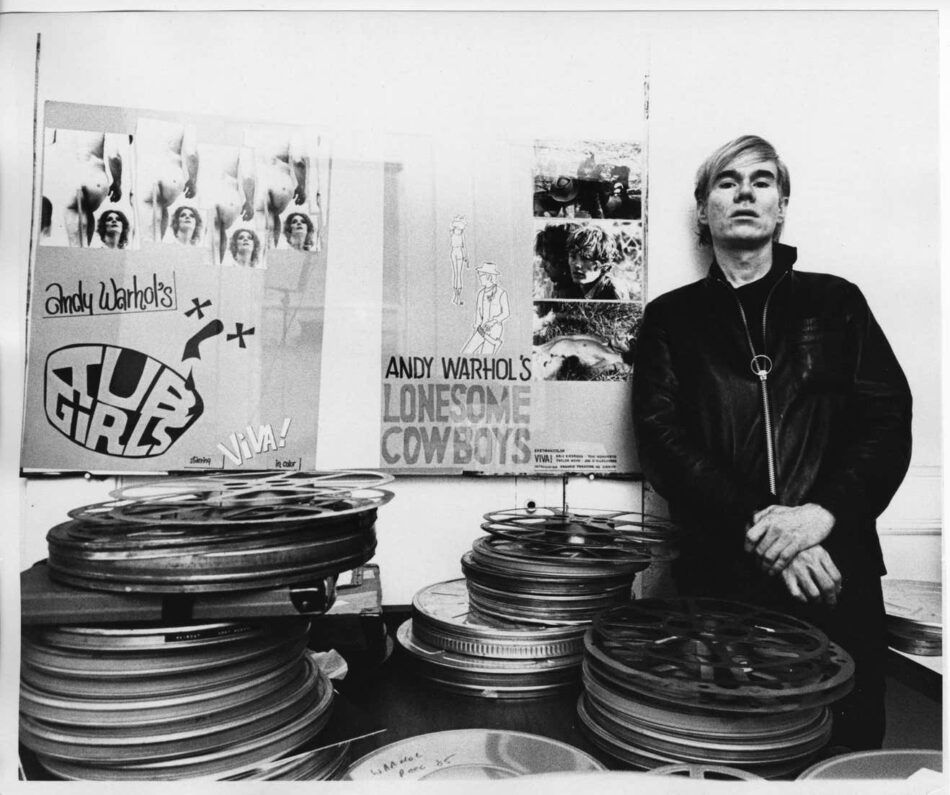

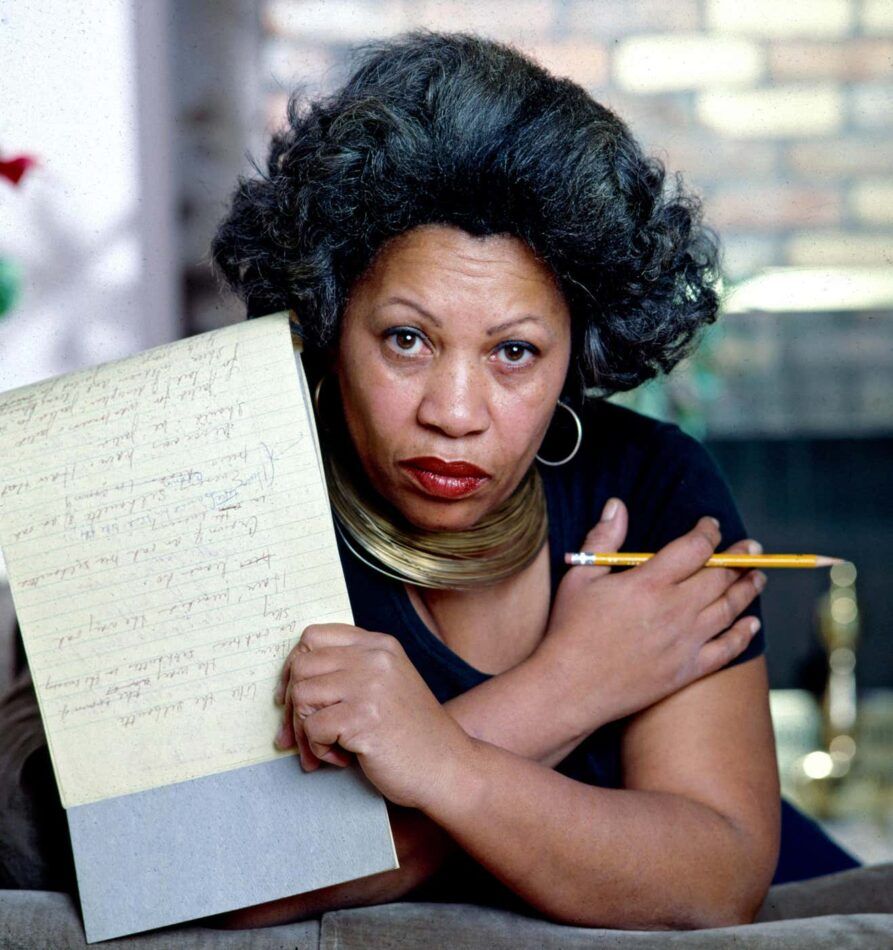

In fact, the breadth of his repertoire makes name checking an impossibly reductive exercise. Even a cursory glance at Mitchell’s huge body of work suggests the immensity of his legacy. Among the boldface names he worked with were Salvador Dalí, Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, Leonard Bernstein, Liza Minnelli, Alfred Hitchcock, Andy Warhol, Carly Simon, Jack Nicholson, Toni Morrison and Lauren Bacall, to call out just a few.

During World War II, when he was only 16 years old, Mitchell photographed Veronica Lake for a Daytona newspaper. It was his first celebrity gig, but that didn’t stop the audacious wunderkind from asking the actress to sweep back her signature “peekaboo” locks so he could get her full face in the frame. Lake, who was in Florida to help the war effort and at the peak of her career, politely obliged, and the two later became lifelong friends.

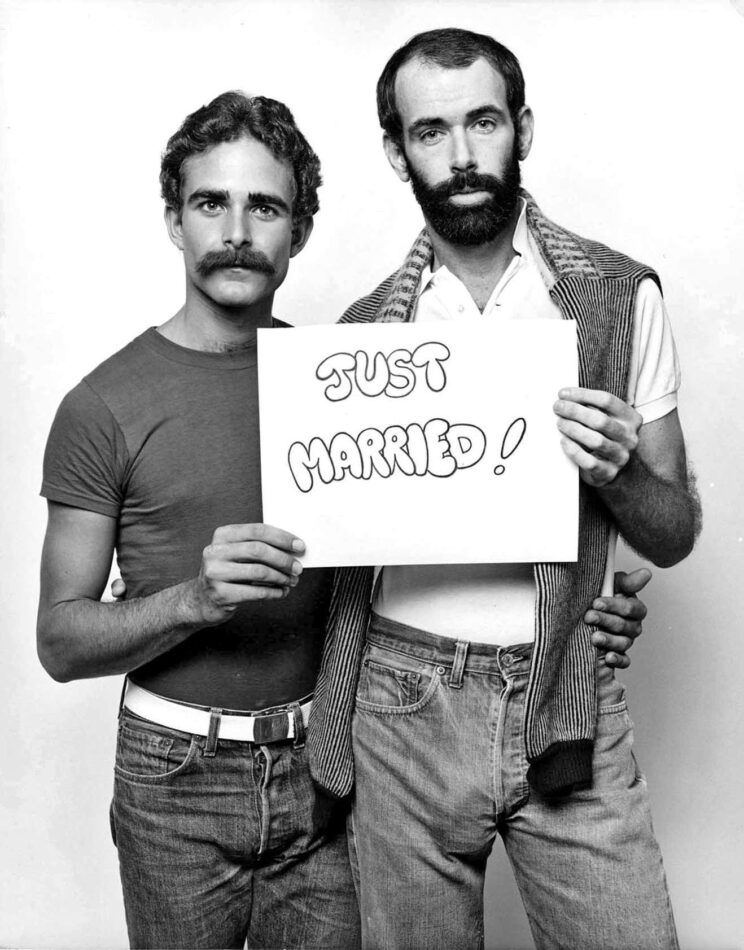

Mitchell, who was openly gay (his long-term partner and manager, Robert Plavik, died in 2009), also struck up a close relationship with Gloria Swanson. From 1960 to 1970, he served as her personal paparazzo, snapping a variety of “candid” shots of the aging but eternally glamorous actress as if she were a pre-mobile/pre-social-media reality star. He captured her being chauffeured in her Rolls Royce (apparently she’d had the car’s doors monogrammed and equipped it with custom-made Cartier travel cases), sitting at the table in her Broadway dressing room, lounging in the bath and even wired up to an EKG machine in her doctor’s office.

“Jack loved going to the ballet, the theater, the opera and to art galleries,” says Craig Highberger, a friend of the late photographer and the executive director of the Jack Mitchell Archives. “He collected art and was a great storyteller and keen conversationalist. In fact, he held what he called his weekly symposiums, which were Friday-night cocktail parties where the conversation would revolve around the latest cultural events.”

Highberger made a 2006 documentary about Mitchell titled My Life Is Black and White, featuring interviews with playwright Edward Albee, choreographer Merce Cunningham and the photographer’s friend and former colleague Lonnie Schlein, photo editor at the New York Times for more than 35 years. Schlein helped to arrange some of Mitchell’s most ambitious shoots, including one taken in 1980 capturing a host of Broadway performers, among them, the casts of A Chorus Line, Annie and Evita. In the foreground of the shot, you can spot a young Glenn Close, then starring in the musical Barnum.

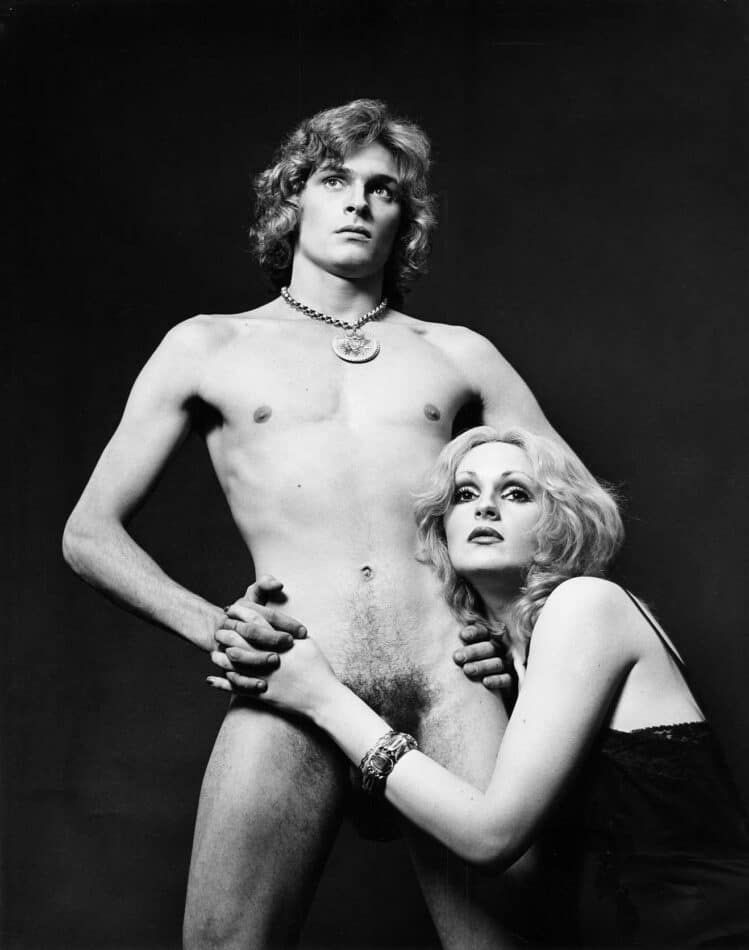

Highberger traces his connection with Mitchell to his high school days, when he came across one of the photographer’s pictures of Andy Warhol superstar Joe Dalessandro in the magazine After Dark. That inspired him to go to New York City, where he attended NYU film school, met Warhol and his entourage, who later became the subject of Highberger’s 2004 documentary Superstar in a Housedress, and eventually formed a close friendship with Mitchell himself.

“I used Jack’s photographs in the film, which then led to my making a documentary about him. So, his portraits of Warhol and superstars Jackie Curtis, Candy Darling, Holly Woodlawn and Joe Dallesandro, all of whom I knew personally and worked with, are part of my history and very special to me,” says the archivist and filmmaker.

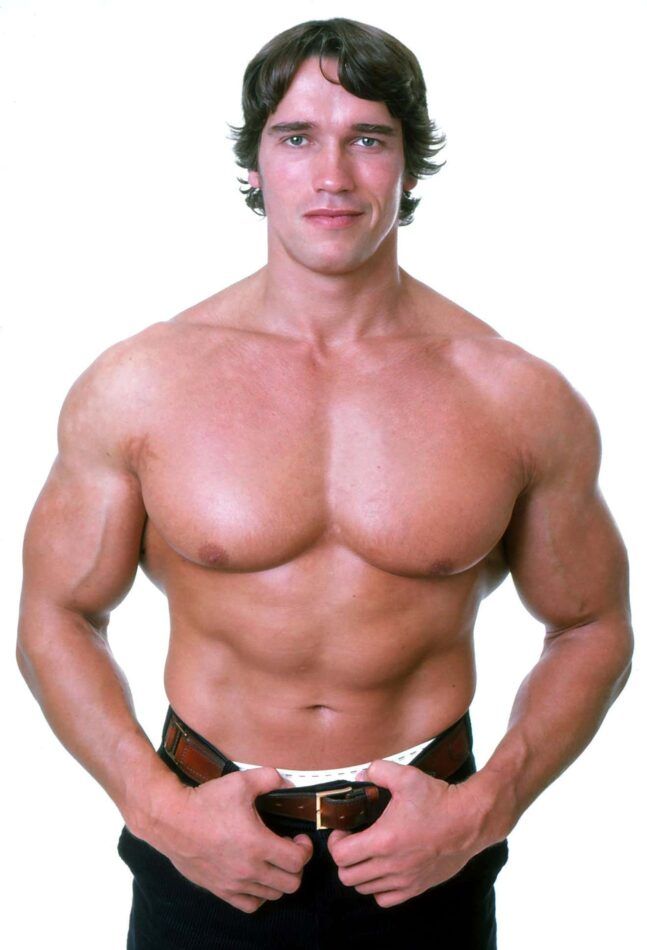

The diverse publications in which Mitchell’s work has appeared — in addition to the New York Times, there’s Rolling Stone, Dance Magazine, People, Vogue, Vanity Fair, Time, Harper’s Bazaar and Newsweek — testify to the power of his arresting visual language and its ability to transcend themes and disciplines. His work for After Dark arguably helped to boost the careers of two famous sitters, although the images couldn’t be more dissimilar.

The first shows a scantily clad, pumped-up Arnold Schwarzenegger in his bodybuilding prime, while the other is a softly focused, kittenish portrait of the 27-year-old Meryl Streep. Sitting on the floor with her knees bent, the actress cuts a confident figure — she had already garnered critical acclaim for a number of off-Broadway shows, although her star turn in Kramer vs. Kramer was still three years away.

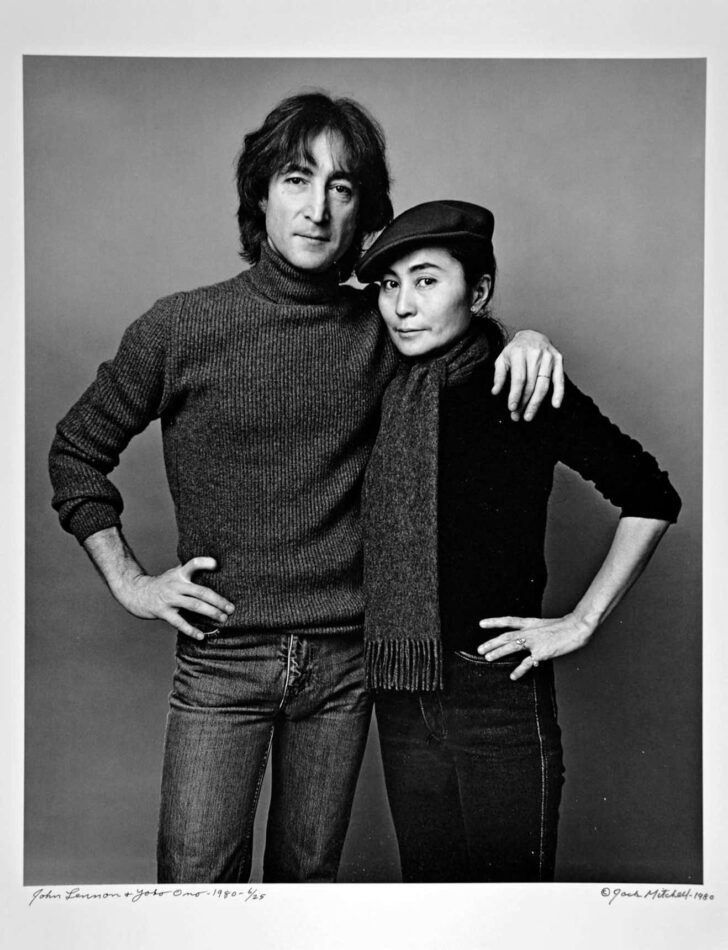

Mitchell also famously shot a series of intimate portraits of John Lennon and Yoko Ono in November 1980, just one month before the Beatles singer was assassinated. A picture from this session became the cover of People‘s memorial issue, one of the magazine’s best-selling editions to date.

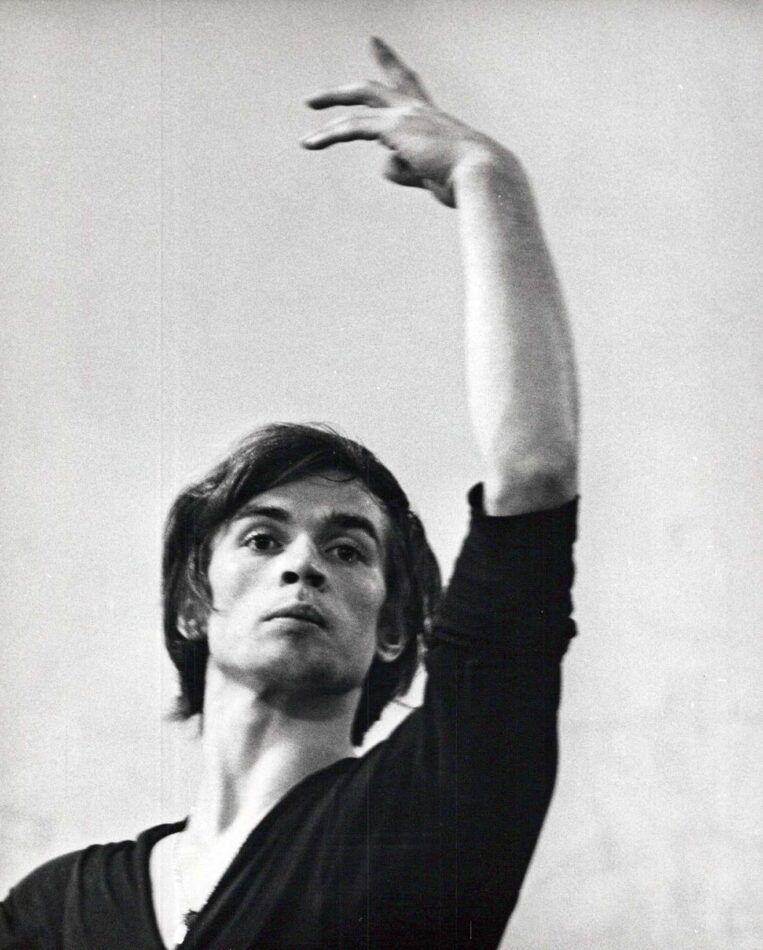

The showbiz gloss should not distract from Mitchell’s meticulous approach to photography. He insisted on producing his own prints in order to achieve what he deemed museum-quality patina and definition. “Jack shot many rolls of black-and-white film, and always some color transparencies, of every famous person he photographed,” says Highberger, who spent four and a half years cataloguing Mitchell’s thousands of silver gelatin prints. “However, he only printed a couple of his favorites from the session, and only those were published at the time. Going through his proof sheets, I found many wonderful additional shots, including great portraits of Rudolf Nureyev’s debut performance and Andy Warhol laughing at a cocktail party with Veronica Lake.”

Highberger estimates that there are more than a million negatives in the archive. “I have found wonderful treasures. including many of Jack’s famous subjects holding his studio cat, Nik, named after his favorite camera, Nikon. French mime artist Marcel Marceau and Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn both took a shine to Nik,” he confides.

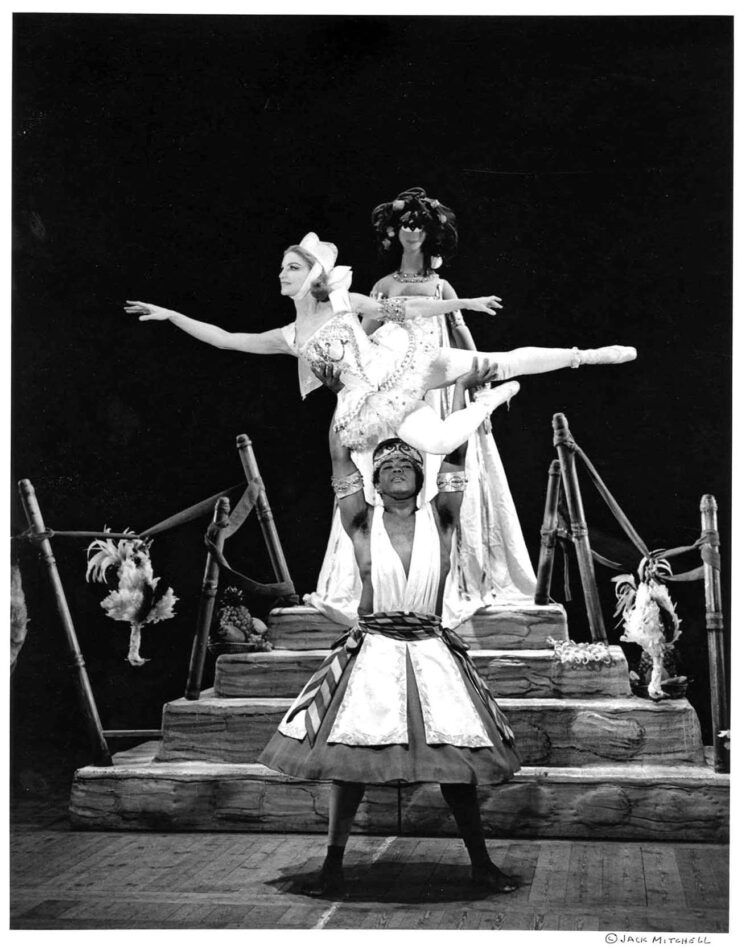

In the world of dance, the field for which Mitchell is best known, his striking and incisive shots of legendary performers and choreographers reflect the visceral energy that these luminaries introduced to the discipline in the 1960s and ’70s, widely considered the Golden Age of American dance theater.

“Jack’s photographs of dancers during his lifetime are a historic chronicle of an amazing period in dance history. He was Alvin Ailey’s dance company photographer from 1961 to 1994,” says Highberger, noting that Mitchell’s collection of 10,000 black-and-white Ailey prints now belongs to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“He also photographed all the major dance companies — helmed by the likes of Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, Twyla Tharp,” Highberger adds. “And he shot innumerable artists, including Erik Bruhn, Carla Fracci, Natalia Makarova, just after she defected, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Rudolf Nureyev, Cynthia Gregory, Gelsey Kirkland. The list is endless. Jack shot over 160 cover images for Dance Magazine, more than any other photographer, and had been a contributing photographer for the magazine since 1952. His dance work is an important part of his legacy.”

Mitchell’s dance images are at once ethereal and powerfully dynamic. Not only do they evoke movement through elegant poses and disciplined muscular tension, but they also convey an intimate energy radiating directly from his subjects, as if he had magically unlocked a reflective mood or a character trait, without contrivance. Dancers are at ease, naturally in their element, whether caught in midair, seemingly defying gravity, or frozen in a statuesque stance.

“Always ask for more and sometimes you’ll get it,” sums up Mitchell’s approach to getting his athletic subjects to leap or twirl as high as they could for his aerodynamic shots. One need hardly have requested the same of him: He had reached the pinnacle of perfection, and he remained there.