Photo by Aveline & Quenetain, courtesy of TEFAF

The European Fine Art Fair, or TEFAF, takes place in March in the Dutch city of Maastricht every year, and it has long been considered the most important art and antiques fair in the world. Now, an offshoot is coming to New York. From October 22 to 26, TEFAF New York Fall will take over the Park Avenue Armory, with 65 dealers in fine and decorative arts created prior to 1920. (In May, a second show at the Armory, TEFAF New York Spring, will have post-1920 modern and contemporary art and design.)

It’s a bold but a well-considered move. While Americans make up a tiny fraction of the 70,000 visitors to Maastricht, that portion accounts for a significant number of the most important sales. By bringing a smaller version of TEFAF to the United States, organizers hope to attract more American collectors and increase sales. Dutch firm Tom Postma Design, which has much experience with designing blue-chip fairs and gallery spaces, created the overall scheme of the booths.

Many TEFAF dealers, naturally, are promoting works created by Americans for the American audience. Here, we take a look at some of the most compelling offerings from across the continents and centuries.

Herter Brothers Collector’s Cabinet, ca. 1879

Hirschl & Adler Galleries of New York will show a splendid Aesthetic Movement collector’s cabinet made circa 1879 by the Herter Brothers, renowned German cabinetmakers who emigrated to New York. Made of rosewood with marquetry and intricate inlays of gold, silver, pewter, brass and mother-of-pearl, this cabinet has all the bells and whistles, including four Tiffany panels in mixed metal.

“We sold it once in the 1980s, and it was in the Herter Brothers show at the Met in 1994,” recalls Liz Feld, director of the gallery. “Now we have it back. We think it was originally commissioned by Mary Jane Morgan, a famous collector of the Aesthetic Movement in New York.”

John Sloan, Orchard, Coming Storm, 1907–8

Bernard Goldberg, a private dealer in New York, is devoting his booth to first- and second-generation artists of the Ashcan School, with paintings by early 20th-century adherents like John Sloan, William Glackens, Guy Pène Du Bois and Edward Hopper. One oil looks like it was inspired by Hurricane Matthew: Sloan’s Orchard, Coming Storm, from 1907 or ’08, depicts a tree battered by wind beneath furiously stormy skies. It was painted out-of-doors with thick, animated brushstrokes — mostly in silvery grays and greens — and looks very modern.

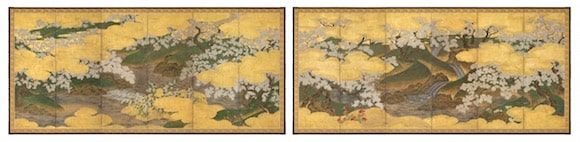

Japanese Cherry Blossom Screens, Momoyama Period

Completely different is the refined brushwork of a pair of Japanese screens that New York dealer Erik Thomsen will show. Painted during the Momoyama period (1568–1615), the pair of six-panel folding screens depict cherry trees in full blossom in the countryside south of Kyoto. The snow-white flowers are given dimension by thick application of a pigment made from crushed seashells. Stylized golden clouds float across green mountain slopes. The inlaid metal mounts on the lacquered wood frames, like the paintings themselves, are in mint condition. Each screen is more than 5 feet tall and 12 feet wide. “Because of their size, I think they were commissioned for a temple,” Thomsen says. “They are extremely rare. In fact, they may be the earliest known depictions of this classic subject — the symbol of early spring.”

Hinton House Elephant Table, ca. 1735

Ronald Phillips of London has a showstopper: a famous elephant console with lion-paw feet, circa 1735. It is from Hinton House in Somerset, a medieval hall house from 1500 with alterations that various Lords Pouletts commissioned by Sir John Soane and James Wyatt.

The compact George II console has an Egyptian porphyry top to match the simulated porphyry base. A golden lion skin frames the black elephant head. It curls its trunk around a gilded garland. Ann Getty has the matching stools in San Francisco. “This console is the best of the best and unique,” says Simon Phillips, the owner of Ronald Phillips. “It’s out of this world.”

James I Silver-Gilt Tankard, 1620

S.J. Shrubsole, the New York specialist in antique silver, has a real find: a handsome James I gilded tankard with stone decoration. “It’s the only fully marked James I object that exists,” says Tim Martin of Shrubsole. “It is embellished with a small-veined Sussex marble that was mined in the 16th century, a serpentine green stone inflected with red. It’s very rare.”

Blue-and-White Porcelain Cistern, ca. 1740

The Dutch dealer Vanderven & Vanderven Oriental Art is offering a unique discovery: a blue-and-white porcelain water cistern, circa 1740, decorated with the “archer pattern.” In a cartouche on the front, an archer shoots a crossbow. It is attributed to Cornelius Pronk, a draughtsman the Dutch East India Company hired to produce Chinese porcelain designs for the Dutch market. He drew European versions of Chinese scenes (called chinoiserie), which were wildly fashionable in the 18th century. This was a commission made to order in China for a Western dining room.

“There are only three other pieces known with that design and this is the only one that is on a cistern,” says the gallery’s Nykke van der Ven.

Merry-Joseph Blondel, Sappho Recalled to Life by the Charm of Music, 1828

Sappho’s ill-fated love affair inspired paintings by Baron Gros (1801) and Jacques-Louis David (1809) before this one. Here, we see the influence of Blondel’s friend and mentor, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, in monumental, highly finished composition, the classicizing style and the theatrical effect of light and gesture. “Blondel had a successful career as official painter and received prestigious commissions for palaces, museum and churches,” says Tom Davis, gallery director of Daniel Katz. “He painted several ceilings in the Louvre and decorated the Galerie de Diane at Château de Fontainebleau.”

Davis admires Blondel’s mastery: “The marble floor in chiaroscuro, the smoke from the incense burner, the light from the background sky — with this painting the meaning is incidental. It’s all about the sensuality of the scene.”

Neo-Gothic Center Table, ca. 1867

Maison Gerard will share its TEFAF booth with Paris wallpaper specialist Carolle Thibaut-Pomerantz. “Because she is bringing a beautiful embossed-leather wall covering of imperial provenance, I thought it would be natural to showcase a table of royal provenance,” says the gallery’s managing partner, Benoist Drut. “So I’m bringing a center table that was specifically commissioned for Schloss Marienburg, a neo-Gothic castle built in 1867 by George V, the last king of Hanover, for his wife’s birthday. I love the country look of this table, which is beautifully studded with little brass balls.”

Gustave Courbet, La Liberté, 1875

Richard L. Feigen is showing a large, proud bronze bust of the figure Liberty created by Gustave Courbet, the painter who led the Realist movement in 19th-century French painting. It was cast in Paris after Courbet had exiled himself to Switzerland. (He was briefly imprisoned for participating in the destruction of the Napoleonic Vendôme Column during the Paris Commune in 1871).

Courbet was so happy in Switzerland that he wanted to donate a sculpture of Helvetia, the female personification of the republic, to his town, but the residents objected to her Phrygian cap, a symbol of the French Revolution. So he agreed to rename her Liberty. That version, cast in iron, remains in the town. The bronze Liberty ended up in the collection of the Baron of Bastard, a member of one of France’s oldest noble families. “It’s in the original black wooden box, with the baron’s title and Freemasonry symbols,” explains Frances Beatty, president of Feigen. “He must have been a Freemason, even though in 1875, it was not so acceptable for an aristocrat to be a Freemason.”

Courbet died in 1877, at age 58, right before he was due to pay the first of 33 yearly installments of 10,000 French francs for the restoration of the Vendome Column. He died just in time. “This is the only Liberty in bronze, and it has a wonderful patina,” Beatty points out. “Jeff Koons would love it.”