June 1, 2025Something happened in 1920s Los Angeles that would shape the area’s design legacy forever: Rudolf Schindler and Richard Neutra, two extraordinarily talented European architects schooled in the modernism of the notoriously decoration-averse Adolf Loos, arrived. Lured to Los Angeles by maverick American designer Frank Lloyd Wright, who invited the pair to assist him with an expansive complex for the heiress Aline Barnsdall (which became known as Hollyhock House), the Austrian-born architects stayed in the region, creating radical new homes with crisp horizontal lines, flat roofs, cantilevers and open plans that maximized Southern California’s beauty, climate, space and light.

Their California Modernism offered a fresh new aesthetic for this sunny corner of the new world, an avant-garde alternative to the more decorative traditions that had also migrated west from Europe. Many Angelenos, newly monied thanks to the booming film and petroleum industries (among others) and eager to build new homes, turned to the revival of past architectural styles — Tudor, Mediterranean, Spanish Colonial, Gothic — to demonstrate wealth and taste.

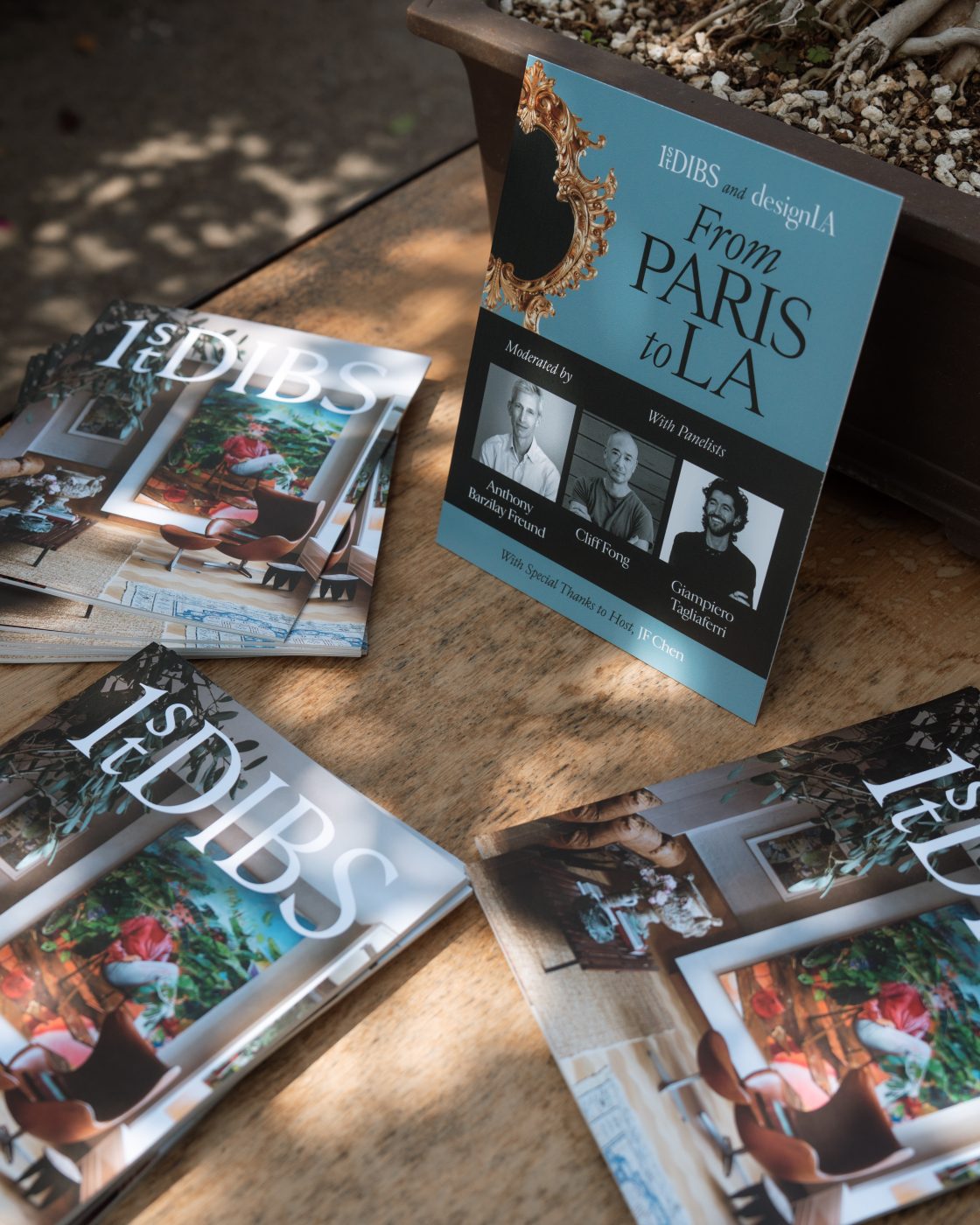

The infusion of internationalism in the region never stopped, and the Europe-to-California pipeline continues making its mark today. For the 15th edition of the annual design event LA Legends — held in early May and organized by Design LA (formerly known as the La Cienega Design Quarter) — the theme was Wanderlust, which seemed like a perfect jumping-off point for a discussion presented during the event by 1stDibs.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the website. During its quarter century in operation, 1stDibs has “wandered” the planet, beginning with a small group of dealers at the Paris flea market and expanding into markets around the world and across the United States — from the Hamptons to New York City, New Orleans and, ultimately, Los Angeles. In the same way, countless European design currents have made a global trek, manifesting magnificently once they reached L.A., and at Legends, 1stDibs editorial director Anthony Barzilay Freund spoke with two esteemed local interior designers known for gracing their spaces with an expansive European sensibility: Cliff Fong and Giampiero Tagliaferri.

An edited version of their talk, which took place at venerable design gallery JF Chen, appears below. In it, they discuss their love of vintage decor, the design-fashion connection and the pitfalls of monolithic mid-century modernism.

Anthony Barzilay Freund: I’m so excited to be here with these two talented gentlemen. I’ll briefly introduce them.

Cliff was born in New York but had a diverse upbringing and has lived in many countries around the world. He’s been part of Los Angeles’s fertile design community for two decades as a noted interior designer, fashion designer and entrepreneur. He’s the founder of the design firm Matt Blacke Inc., as well as the creative director and partner of Galerie Half. Cliff’s latest venture, Faire du Vert, is an outdoor- and garden-inspired showroom with an emphasis on architectural vessels, significant historical design and rare plant material.

Meanwhile, Giampiero grew up in Milan and began his career as the creative director of Oliver Peoples, which first brought him to L.A. Three years ago, he founded Giampiero Tagliaferri Design, an architecture and interior design studio with offices in both Los Angeles and Milan. His work merges Milanese sophistication with California ease and is rooted in a deep passion for craftsmanship, collectible design and richly layered, narrative-driven interiors.

When you both agreed to do this talk, I was struck by how many qualities you share, even though you’re coming from very different places. Let’s start by discussing your experience living internationally and how that has informed your approach to design in L.A.

Giampiero Tagliaferri: I grew up in Milan. I’m not a trained architect, and I didn’t study design, I studied business. I learned about design by living it. When most people think of beautiful Italian cities, they think of Rome and Venice and Florence. Milan doesn’t come up, but really, it is a beautiful city that has many layers. And you have to discover that beauty layer by layer. So, you go inside of a courtyard, and there is a beautiful garden. You look at the detail of a corner of a building, and you discover that it has been made in different materials that are matched together. That has informed my way of designing.

When I moved to California, it was completely different. Milan is very austere, very dressed up, very proper. California is the opposite and very open to the outside. This was a discovery for me and a new lens through which I look at design.

Cliff Fong: I spent a fair amount of time in Europe — where my father lived — as an adolescent. So then, when I was studying art history in college, my travels gave everything a context. I was able to appreciate and cultivate a relationship with design on a historical and cultural level.

In Europe, when you see the juxtaposition of contemporary art or design in a seventeenth-century building, it creates such an interesting contrast — it’s almost revelatory. And we don’t really get to feel that or see that in the U.S. I want to bring that level of interest to projects here.

Freund: You both come from the world of fashion. How has that experience colored the way you approach interior design?

Tagliaferri: For Oliver Peoples, I did a lot of campaigns for sunglasses inside modernist houses. That was the aesthetic that I wanted to convey about the company. I wanted to highlight the cultural relevance of Los Angeles, the historical modernism — to show that it wasn’t just beaches and the palm trees. I made this correlation for the brand, and I was inside many incredible historical homes — by Richard Neutra, John Lautner, Charles and Ray Eames, Craig Ellwood. And when you shoot a campaign, you start looking at the lighting, because it is key for photography. And you realize that these architects literally studied every corner of those houses in order to get the best of the light and to get this connection between interior and exterior. That is very important to me.

Freund: The light is remarkable. As a proud New Yorker who thinks my city has all others beat, I reluctantly admit you’ve got something good going on here with the light. Where did fashion take you, Cliff?

Fong: For me, fashion was a bit of a tangent. But fashion, design, fine art — they are all manners of expression and communication and how we take care of ourselves. I try to demystify the process of designing a home by explaining that feathering a nest is not so different from getting dressed every morning. Just as your favorite old pair of jeans can look good with a tailored sport coat or a beautiful cashmere sweater, if you have the right kind of textile on the floor — a beautiful old worn, antique carpet, say — you can put a tailored sofa on top of it or you can put overstuffed, shabby-chic bohemian seating on it. Or anything in between. And then when it comes to accessorizing, the sky’s the limit. You could be a T-shirt-and-jeans person, but if you’ve got the right heels and handbag, you’ve got a look. And I think for a lot of people, breaking that down in simple terms when looking at a home has really helped them understand the process better.

Freund: I think some people are intimidated by home design. I see people who very easily spend many thousands of dollars on a sweater, but they’re reluctant to do that on a vintage sconce.

Fong: Here in L.A., you find people with a two-million-dollar painting and a three-hundred-thousand-dollar car in the garage, and all their furniture is from a big-box store. I’m not saying that everything has to be impeccable, but things should have authenticity and meaning and be personal. Design is an opportunity to make our lives bigger, to experience more.

Freund: Are there any movements here in L.A. right now, or makers, that you’re excited about or you’re seeing your colleagues excited about or you’re noticing and thinking, “Wow, I’ve never seen that before”?

Tagliaferri: I don’t like following trends, but I would say there is definitely more attention to Italian design. The greats, of course — Gio Ponti, Carlos Scarpa — but even lesser-known designers. I think in L.A., for many years, it was all about the French, but there is a shift from just one mono kind of look toward more obscure types of designers, either Italian or French or Nordic.

Fong: Sometimes, there are these zeitgeists around certain kinds of looks. But by the time you recognize a trend in design, it’s kind of over already. But I will say right now there are only a few people who are interested in interiors that feel as used and abused as I like. I like things that are evidential of their history or their passage through time.

Freund: Americans tend to like pristine. They like things sparkling new. Giampiero, is it hard to convince your American clients to embrace the kind of patina and layers you mentioned?

Tagliaferri: I think the importance of vintage pieces is really that they add the lived-in effect. If you put a brand-new piece in a house that is new or just renovated, it all looks too new, too fresh. We are lucky that our clients understand. Some used to prefer a perfect shiny house, and then they decided, wait, there’s another way. Maybe they traveled more. In Europe it’s normal to grow up in houses that are five hundred years old.

Fong: I find that those kinds of environments are infinitely more intriguing and sexier than those where someone went to a showroom and bought everything from B&B Italia or Minotti. I love what those companies do, but I wouldn’t want to live in an environment that was purely that, and I wouldn’t want a client to do that either.

Freund: Nor would you create an environment that was entirely mid-century modern, right? Nobody wants that.

Fong: No, it all just feels cliché. Also, when you’re living in Los Angeles, if you’re not careful, too many things can look like set decorating.

Freund: Do antiques — eighteenth-, nineteenth-century pieces — play a role for you?

Fong: I love that. I really like seeing history, and I truly think it’s a privilege to be able to engage with a fine antique or a piece of historically important design, whether it’s twentieth century or seventeenth century.

Freund: Is there a place for antiques in postwar modernist L.A. houses, with their glass and open spaces?

Tagliaferri: I don’t incorporate a lot of antiques. There are little pieces here and there, but for me it’s more the twentieth century. But as Cliff was saying, it’s the idea of creating a narrative. The way I like to design a space is to create the feeling that this person lived in the house for many decades. So, you have pieces from the nineteen forties, fifties, sixties, seventies, eighties — and it is all mixed together. Of course, the trick is, how do you mix them together? The way you put certain pieces together is what defines style.

Fong: When you have actually created something that feels unusual and unexpected, drawing from different historical periods — that feels like a big win for me.