The highly polished, saturated and intricately composed photographs of David LaChapelle possess the surreal wildness of fever dreams, concocted as they are out of the imagery of celebrity, eroticism and modern Americana, and spiked with religious allegory and forebodings of doom. Such work has made the 54-year-old among the most influential art and celebrity photographers of his generation. You might say LaChapelle sprung straight from the head of Andy Warhol, whose campy silkscreen fusions of the glamorous, the transgressive and the everyday forever changed contemporary art.

Like so many young gay artists who came out of the 1980s downtown New York scene, LaChapelle’s escapist visions arose out of a lonely, bullied adolescence. Although born in Connecticut, the photographer spent his early childhood in North Carolina, the youngest of three children. Later, when LaChapelle was in his early teens, his family moved back to suburban Connecticut, but his cowboy costumes and gender-bending ways did not earn LaChapelle friends among his new preppy classmates.

By high school, he felt terrorized and suicidal. He fled to New York, where his good looks got him a job bussing tables at Studio 54. It was there that he reputedly first met Warhol, who had been his favorite artist since he first gazed upon a Gold Marilyn, while on a fourth-grade field trip to a museum. His parents eventually retrieved him from New York, and, sympathizing with his plight, sent him off to the North Carolina School of the Arts. Despite a more embracing atmosphere, he didn’t stay long.

A sojourn in London followed, where LaChapelle became part of the club scene that included performance artist Leigh Bowery and choreographer Michael Clark. When he returned to New York, around 1983, the punk-inflected downtown culture was churning out gritty new art. Keith Haring’s gay-themed Pop-art graffiti was in everybody’s face, and Robert Mapplethorpe’s S&M photos were on gallery walls.

But as quickly as that raw, raucous imagery emerged, it withered as AIDS culled downtown’s brightest lights. After a boyfriend died of the dreaded disease, the specter of death hung over LaChapelle, who was too frightened to be tested. Years later, when he finally was ready, LaChapelle was shocked to discover he was HIV-negative. A bipolar condition that took years to be diagnosed further contributed to his ongoing emotional turmoil. It likely also accounts for his various, and sometimes contradictory, stories regarding his life, and for that matter, his age.

Having scored a show of his black-and-white photography — already vaguely campy and transfiguration-obsessed — at New York’s then-fledgling 303 Gallery in 1984, LaChapelle attracted the interest of Interview magazine. Warhol was then at the zenith of his influence in both the art world and the downtown scene. Recognizing LaChapelle’s potential as an eye-catching celebrity photographer, he put him on staff, providing him with the creative milieu where his distinctive talent might develop. “Do whatever you want,” Warhol told him, “as long as they [celebrities] look beautiful.” Soon after, 303 dropped him from its roster; back then, emerging art stars weren’t supposed to have glamorous day jobs.

When Warhol died unexpectedly in 1987, LaChapelle was fired. Many in the industry thought his career was finished, but he regrouped. There were editorial assignments for i-D, The Face and later for Vanity Fair, Vogue Paris and Rolling Stone. He also made excursions into advertising. One of his most talked about campaigns was a provocative print ad for Diesel jeans inspired by the famous photograph of the V-J kiss in Times Square, but this time showing Tom of Finland–type sailors in passionate embrace.

Just last winter, he reprised his association with the Italian fashion company for a new print and video campaign, called (fittingly for the times), “Make Love, not Walls,” which features the beauteous ballet star Sergei Polunin passionately thrusting his bare-chested, denim-clad body against a border wall, when a stunning band of models and dancers, also scantily attired in denim, bursts forth from the other side and all engage in amorous celebration. There is also a rainbow-colored inflatable in the shape of a tank. The concept and imagery are classic LaChapelle.

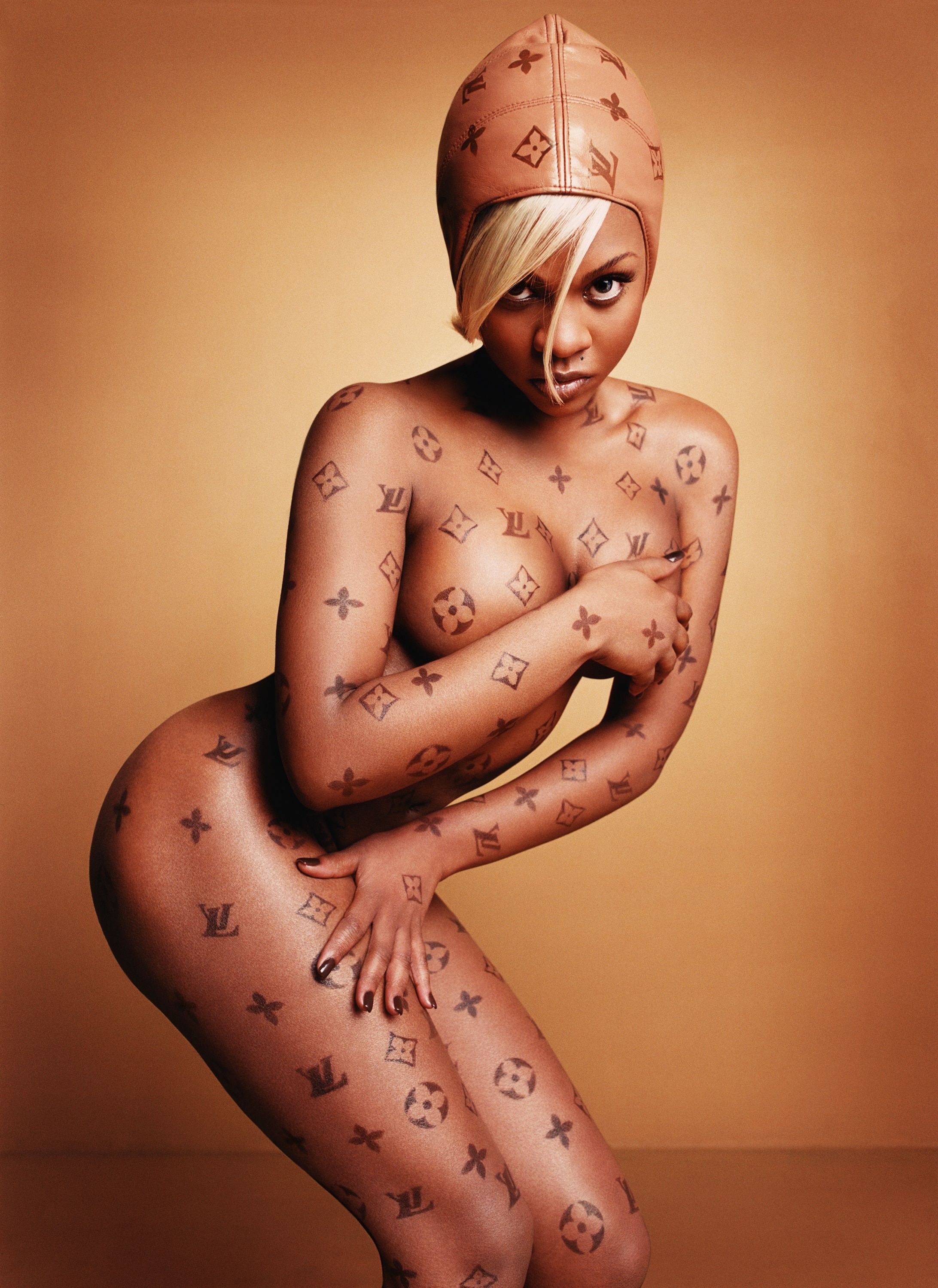

After being without an editorial home for several years, LaChapelle finally found a base at Details, where he was again encouraged to let his freak flag fly. So arresting were his images that it wasn’t long before “the Fellini of photography,” as New York magazine dubbed him in 1996, was again working for Interview. One of his most emblematic pictures from this era was a Lil’ Kim cover for that magazine, featuring the rapper’s nude body emblazoned with Louis Vuitton insignia.

Such visually zany, socially astute portraits, prompted Richard Avedon to liken LaChapelle to a photographic Magritte, while also winning him invitations to direct music videos for such talents as Christina Aguilera, Moby and Amy Winehouse. By 2004, LaChapelle had staged Elton John’s over-the-top Red Piano concert tour.

In the early 2000s, LaChapelle ventured into film, investing his own funds into making the documentary Rize, about the emergence of krumping, a street dance phenomenon in South Central Los Angeles. Brimming with an urgent beauty and vibrancy, the film deeply affected the acerbic critic Richard Ebert, who declared: “the most remarkable thing about Rize is that it is real.”

Despite widespread praise, the film, which premiered at Sundance in January of 2005, was not a box-office success. Other setbacks soon followed. A fashion spread that LaChapelle shot that June for Italian Vogue, featuring models against derelict houses and sandbags in the American South — his vision of a future environmental catastrophe — hit the newsstands just days after Hurricane Katrina.

What was a freak coincidence was viewed as LaChapelle’s cruel and tasteless commentary on the New Orleans disaster. It was the final straw for many editorial clients who had grown weary of his desire for operatic-scale shoots and their accompanying epic budgets.

Then, LaChapelle took on what he once would have considered a dream assignment: directing a music video for Madonna’s new single “Hung Up.” But on a phone call with the singer, the two disagreed over the concept, and LaChapelle, still exhausted and emotionally beat up, actually hung up on the pop star and disappeared. Off on a shoot for Motorola in Maui soon after, he bought a former nudist colony in a remote section of the island, and retreated there with the intention of turning it into an organic farm.

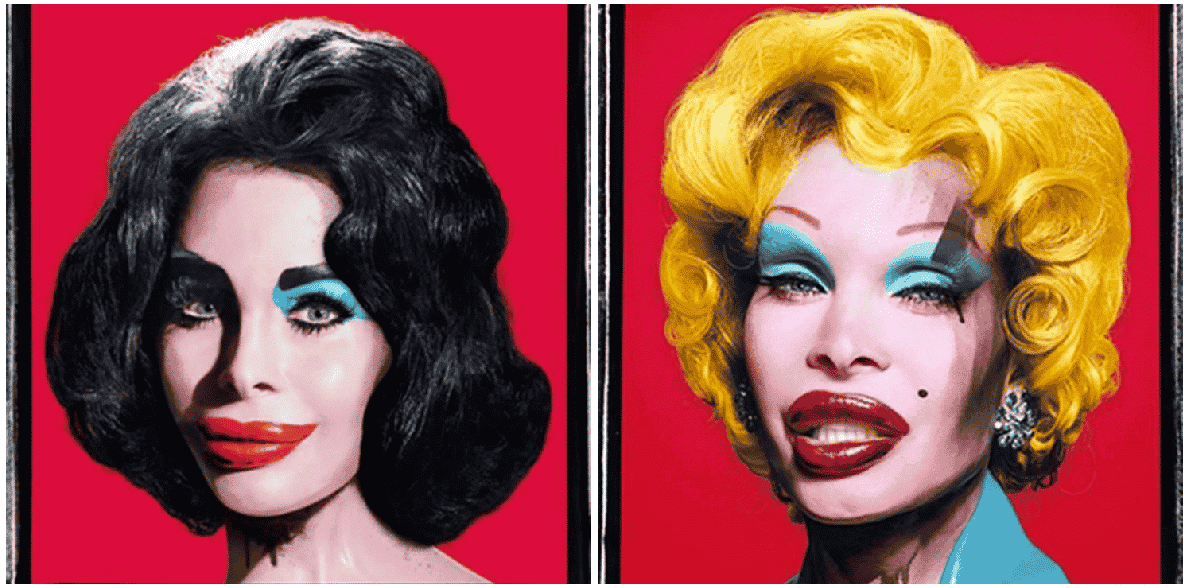

In solitude, LaChapelle returned to his roots as an art photographer. Portraits he took of his longtime friend, the transgender model Amanda Lepore as Andy Warhol’s “Liz” and “Marilyn,” in 2007, marked a return to his beginnings and his passage beyond them. Much like Warhol had done in his 50s, LaChapelle, now in his mid-40s, turned to art history for inspiration.

Amanda Lepore as Warhol’s Liz in Red, 2003; Amanda Lepore as Marilyn, 2003. Courtesy of Staley-Wise Gallery, New York

In recent years, he has shot a series of floral portraits based on Dutch still lifes; created metaphysical and religious allegories in response to masterworks by Botticelli, Michelangelo, Rubens and others; and, perhaps most fascinating, looked to the mournful loneliness of Edward Hopper when creating a series of hyperreal nocturnal images of gas stations in the jungles of Maui.

Demand for his work has never been greater, nor auction prices higher. What he comes up with next is anyone’s guess, but David LaChapelle has proven himself to be an artist with more than one second act.