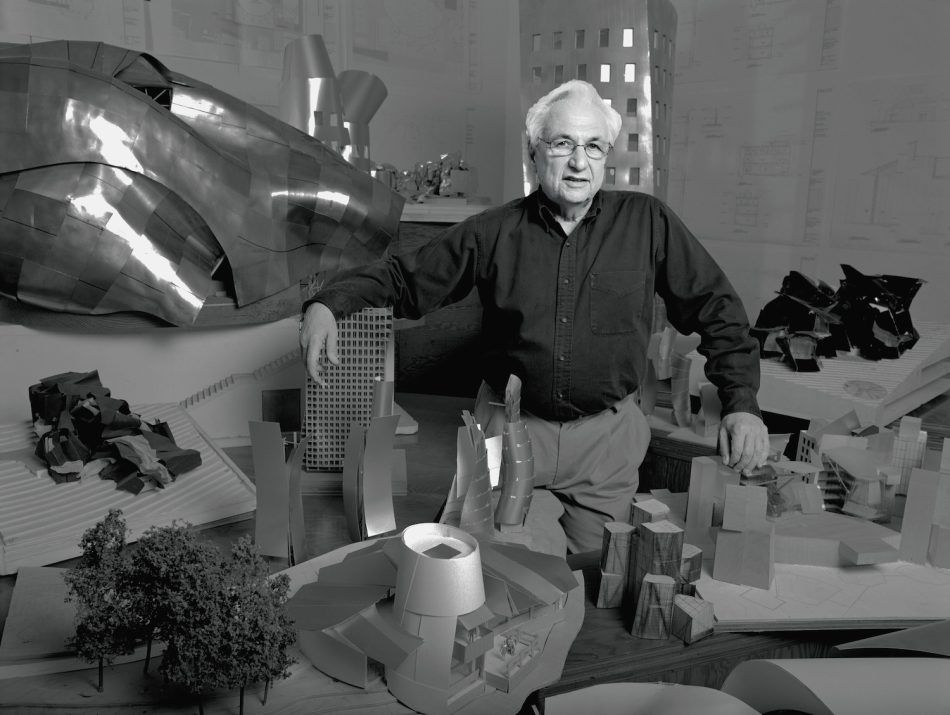

When Frank Gehry died, in December 2025 at the age of 96, he was universally praised as the most important American architect of the past half century. A trio of late-career buildings — the Guggenheim Bilbao (1997), L.A.’s Walt Disney Concert Hall (2003) and the Fondation Louis Vuitton, in Paris (2014) — established his reputation as a master of sculptural forms realized in eye-catching materials.

But long before these city-transforming deconstructivist structures garnered international attention, Gehry was experimenting with form and materials on a much more intimate scale. In 1978, he transformed his own home, a traditional 1920s bungalow in Santa Monica, California, with a wrapper of corrugated steel, plywood and chain-link fencing. Just a few years earlier, he had created a line of furniture called Easy Edges, which used corrugated-cardboard strips laminated in such a way that they achieved surprising strength. Pieces like his Wiggle side chair already evinced the mixture of ingenuity and playfulness for which Gehry is most admired today.

Begun in the late 1970s, Gehry’s second collection of cardboard furniture, Experimental Edges, deployed thicker corrugated cardboard layers that were deliberately set off-kilter, creating dynamic surfaces. In the case of the Grandpa Beaver lounge chair, the collection’s keystone, the effect suggests a pile of wood artfully gnawed on by the titular critter.

The Grandpa Beaver chair currently available on 1stDibs from Lawton Mull is particularly noteworthy since it was commissioned a decade after the collection’s launch by one of Gehry’s great patrons: advertising guru Jay Chiat (1931–2002). Chiat/Day’s Venice, California, headquarters, completed in 1991, were designed by Gehry, who notably incorporated a Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen sculpture titled Giant Binoculars at its entrance. (Today the iconic building is owned by Google.) One can imagine that the Grandpa Beaver occupied pride of place in the agency’s open-plan office.

“There’s something very American about the chair,” says Cordelia Lawton, who runs the Long Island City art and design gallery with her husband, Patrick Mull. “The history, the ambition, the experimentation. It’s joyful, and it has real magnetism. When we put it in the gallery window, people stop all day long, trying to figure out what they’re looking at. Some are horrified, some are compelled, but everyone is fascinated, even if they’ve never heard of Frank Gehry.”

Chiat was not shy about embracing envelope-pushing design. In 1994, he asked the great enfant terrible Gaetano Pesce to create his advertising firm’s New York City HQ, and Pesce delivered an experimental “virtual” office incorporating copious amounts of colorful resin. In this postpandemic age, a workspace that eschews formality for flexibility and fun might be celebrated. At the time, however, it was derided — and it was demolished just a few years later.

But this armchair remains a bold testament to the audacious creativity of Gehry and Chiat — and it’s the perfect perch for any deep-pocketed beaver eager to own a hunk of design history.