Since ancient times, men and women have been attracted to pearls and their aura of moonlit mystery. Natural pearls are quite scarce, adding to their allure — and their cost. For such a gem to be produced, an irritant must enter an oyster shell. The shells, however, are very good at keeping even the tiniest invader from getting inside. Tens of thousands of oysters must be collected from the sea to yield even a baby-sized handful of pearls. So, in the age before cultured pearls, imagine how many dangerous dives had to be made before enough natural ones were procured for a single-strand necklace. And then, imagine how many more dives were needed to create a perfectly matched one.

“Paris, City of Pearls” — on view at L’Ecole, School of Jewelry Arts, in the French capital until June — provides splendid evidence of how wonderful and varied pearl jewelry is. Also on display is a fascinating array of paintings, posters and film clips that illustrate the story of how Paris became the center of the international pearl trade in the 19th century and of the pearl mania that lasted well into the 20th.

The Persian Gulf was long the richest source of fine pearls. At the time the tale told by the exhibition begins, London was the capital of the enormously lucrative pearl trade. Parisian dealers did not wish merely to have a piece of the action — they wanted to control the market. They began to make the long and difficult journey to the Gulf and slowly made progress toward their goal.

Eventually, one of them, Léonard Rosenthal, decided to make a bigger push. He kept an eye on fluctuations in the market, and when an economic crisis caused the British trade to dry up, leaving the Gulf dealers starved for cash, he saw his chance. Endowed with wit, drive and chutzpah, Rosenthal accumulated as much money as he could get his hands on and changed it all into coins — not big silver dollars but small, lightweight pennies. He then headed off to the Gulf, where he had the pennies poured into sacks and loaded onto donkeys. The sight of a long donkey train carrying what appeared to be undreamed of riches won over the dealers. Paris was on its way to replacing London as center of the international pearl trade. And Rosenthal, whose portrait is on view in the show, was on his way to becoming “The King of Pearls.”

When pearls began flowing into Paris in large numbers, the city was enchanted — and the gems showed up everywhere: in films, paintings, books and on artful posters. By the 1920s, bob-haired Jazz Age flappers were dancing in Parisian cafés with long strings of pearls swirling around them.

The mania spread. In New York, railroad tycoon Morton Freeman Plant famously traded his Fifth Avenue townhouse to Pierre Cartier for a double strand of natural pearls, which he gifted to his wife, Maisie. The price of pearls exceeded that of diamonds, rubies or emeralds.

Courtesy of the Albion Art Institute. © Albion Art Jewellery Institute; Henri Vever bodice front, 1905. Collection Faerber © Faerber; Theodoros brooch, 2023. Exhibition Paris, City of Pearls. Photo by Dylan Dubois

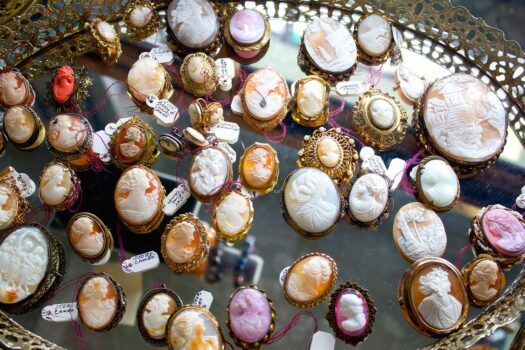

The rich and varied material deployed to illustrate this tale combines with the sometimes amusing and always exceptional pearl necklaces, earrings, brooches, pendants and rings on display, most created during the period covered by that story, to make this an endlessly fascinating exhibition.

Adding to the impact is the show’s location. The gilded Hotel-Mercy Argenteau, home to L’École: School of Jewelry Arts, which is supported by Van Cleef & Arpels — is only a few blocks from the rue La Fayette. In the late 19th century this short street housed 300 pearl dealers, who matched the gems for size, luster and color, producing hundreds of strings a day. Most were Jewish and did not survive the Nazis. Of the few remaining dealers, one firm bears a family name: Rosenthal.