It seems that any lighting fixture having a starburst shape and numerous bulbs on the ends was dubbed “Sputnik” in the Cold War era, after the Soviet Union famously launched its pronged satellite into orbit, in 1957, winning the space race. And uncountable variations have been produced in the decades that have followed.

Here, we look at two very different Sputnik originals: a mid-century-modern classic by Gino Sarfatti and an expressionistic icon by J. & L. Lobmeyr. Fun fact! One of these iconic designs predates the Sputnik satellite by decades.

Gino Sarfatti’s Sputnik Chandelier, A Rationalist Light Veiled in Mystery

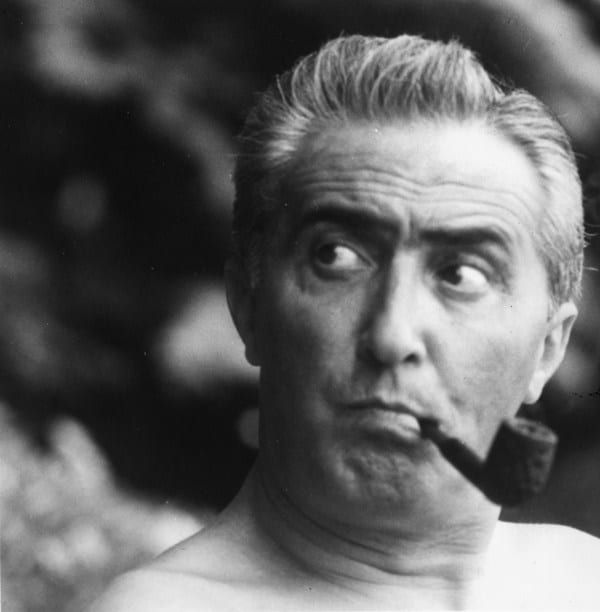

With its array of brass spokes of varying lengths and angles, each crowned with a tiny globe bulb, the Sputnik chandelier is a readily identifiable classic, yet few design mavens are aware that it was originally a creation of Gino Sarfatti (1912–85), a towering figure in the field of mid-century-modern Italian lighting. But then much of the facts about this straightforward fixture are hazy.

What is known is that in the course of his nearly 40-year career, this Venetian-born talent conceived more than 600 fixtures, each one an innovation through its novel shape or construction, or use of a new or experimental component. Early on, he advanced the field by devising adjustable directional beams, providing both up lighting and down; and subsequently enriched the modern lighting vocabulary with fixtures that made use of hooks and weights. So cutting-edge were his “light fittings,” as he liked to call them, that in 1939, he established his own company, Arteluce, to produce them.

Arteluce’s workshop was essential to his breakthroughs, since he devised his designs not through drawings, but by tinkering with various materials and components along with his artisans. Sarfatti fiddled rather than sketched in part because he had no training as an artist or designer. Mechanically minded, he was studying aeronautical engineering at university in Genoa, when his family’s import-export business failed in the early 1930s.

Forced to abandon his studies, he followed his family to Milan, where they’d relocated, and got a job as a salesman. When a friend asked him to make a lamp out of a glass vase, the ever-inventive Sarfatti experimented with placing a tiny light bulb from a coffee maker inside the vessel. He was so captivated by the effect that he began making other ingenious fixtures. Sarfatti’s true vocation, he discovered, was to be a creator of what he called “rational lighting.”

This lover of the technical numerically coded his lights by category. He assigned tens for spotlights, a hundred for wall lamps, and so on. Ceiling lights were designated by 2000. Sarfatti’s official name for the Sputnik chandelier was number 2003, but he was apparently so delighted by its evocative form that he referred to it as “Fireworks.”

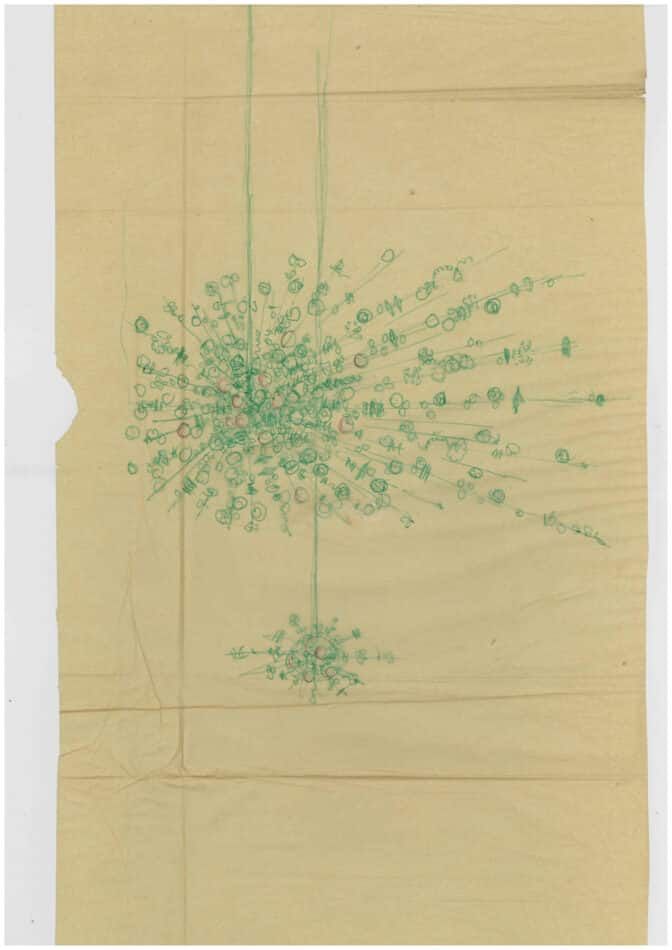

There is a sketch of the fixture that dates from 1939. But it wasn’t immediately put into production. And once the Allies began bombing Milan the following year, Sarfatti and his family fled to the Alps. Since Sarfatti’s father was Jewish, the family feared staying in Italy, and spent the duration of the hostilities in penury in Switzerland. When the war was over, Sarfatti returned to the helm of Arteluce, and sometime in the early 1950s, he produced the first version of number 2003.

Which is why it’s a bit of a mystery how the fixture has come to be called the Sputnik — because the Soviet Union didn’t launch its first Sputnik satellite until 1957. There’s no evidence to suggest that Sarfatti renamed his design to exploit its vague resemblance to the artificial orbiter, nor does that seem like his style.

What’s more likely is that it got that moniker from some design writer or salesperson and it stuck. Which makes the name almost doubly ironic, as not only wasn’t it Sarfatti’s choice, it’s the closest he ever got to aviation design!

A committed functionalist, Sarfatti was always seeking ways to improve on his fixtures and make them as affordable as possible and easy to repair. So, he would likely have been pleased that different versions of his spiky classic are today available at a variety of price points at vintage design stores and home decor shops ranging from swanky Restoration Hardware to style-on-a-budget West Elm.

No doubt, too, he would have appreciated how the earliest remaining versions of number 2003 have accrued in value. You see, Sarfatti was also an avid stamp collector, a hobby to which he devoted the last decade of his life, so he knew better than most the worth of rarity.

J. & L. Lobmeyr’s Sputnik Chandelier, An Opulent Light Inspired by an Accident

There was a time in America when talk of the future elicited a sense of promise and wonder. That time may have come and gone, but some still bask in that glow of retro optimism. Who are those happy few? The ones who live in a home embellished with a J. & L. Lobmeyr “Sputnik” chandelier, with its dazzling spray of Swarovski crystals, or one of the design’s countless variants.

A collision of accident and artistry birthed this enduring classic, wrapped up within a larger story of postwar America, its geopolitical and cultural aspirations and a new worldwide fascination with outer space. How it came to be, and the myriad interpretations that have emanated from that ethereal design, also speak to the nature of originality, authorship and design innovation in compelling ways. Ironically, the groundbreaking series of Soviet orbiters for which the lighting fixture is named figure as little more than a footnote in this design story.

A central character is Tadeusz Leski. Shortly after his arrival in the U.S., this Polish refugee, who was a gifted young artist and architect, became the right hand of Wallace K. Harrison, then one of America’s most influential architects and proponents of the International Style. After Harrison’s firm took the lead in planning Lincoln Center, slated to become New York City’s cultural hub in 1955, Leski was charged with the design of its crown jewel, the Metropolitan Opera House.

Rushing one day in 1963 to finish a rendering for the project, he accidentally let a drop of white paint from his brush splash across his carefully wrought image. But disaster turned into discovery. In the white splatter, Leski saw what looked like a burst of light from a chandelier. With this image in mind, he added a few lines to the white splotches to suggest the arms of a fixture supporting many points of refracted light. And this became the first rendering for the Metropolitan Opera’s now signature “Sputnik” chandeliers.

But that’s just one facet of this story. In gratitude to the U.S. for its rescue of Europe’s postwar economy through the Marshall Plan, the Austrian government was to make a gift of crystal chandeliers to the new opera house from the esteemed Viennese glassware company J. & L. Lobmeyr. Hans Harald Rath, Lobmeyr’s director, proposed a design, but Harrison rejected it. He was in search of a chandelier that looked stunningly new. And the glimmer of that design is what he, and the leaders of the Met, saw in Leski’s exploded light rendering.

It’s not clear if Leski or Harrison went on to make the association of the exploded light with new images of outer space that were then appearing through advanced telescope technologies. But in September of 1963, Harrison sent Rath a letter stating that Rath was to receive two packages from Harrison’s office. One contained Jean-Claude Pecker’s Le Ciel, a then-popular book on cosmology.

He noted a page with a starry image — bearing a striking likeness to Leski’s paint splotch — and wrote that next to it Rath would see the “type of fixture we would very much like to have you study.” (Presumably, it was an enclosed sketch of the fixture by Leski.) The second package, Harrison wrote, would include a model, which was then still being carefully packed. (That would have been essential, as a chandelier with a central sphere encircled by spokes had yet to been seen.)

Who made the connection between Leski’s explosive light and the new awe-inspiring images and theories of the universe? Could it have been Harrison, a man of great erudition and aesthetic sensitivity, and a Francophone? Did he too play a role in this chandelier’s conception? Or did Leski himself make that link?

Having served in the French army, Leski must have read French. That copy of Le Ciel might well have been his. Or perhaps both men came upon the connection together during one of the many heady creative conversations that forged their strong bond.

Today, Lobmeyr insists that the design of the chandelier was entirely Rath’s. There’s some truth to this. Hans Harald Rath poetically translated the architectural sketch by Leski — much later incorrectly attributed to Rath — into a spindrift of crystal stars that was entirely original. And Rath was a design innovator. After World War II, he had been the first to see the shimmering potential of Swarovski crystals in lighting fixtures; until then, they had been used exclusively in jewelry design.

But “authorship is complicated,” as Tadeusz Leski’s daughter Kyna Leski, an architect, has argued, adding, “Guardianship of an idea is perhaps a more accurate characterization.” Four years ago, when the New York Times featured a story about the “space-age origins” of the chandeliers, which focused entirely on Rath, she countered with her own essay on Medium, providing a video of her father relating his brilliant accident, along with numerous documents to support his claim. “At what point does intention declare itself if the beginning is arbitrary?” she writes. “At what point is the accident seized? At what point is the mystery recognized and pursued?”

Wherever the truth lies, on September 13, 1966, as the curtain rose for the opening performance at the Metropolitan Opera House, 12 of these celestial fixtures ascended to the ceiling. The effect was so thrilling, so new, the audience exploded into applause. And from that moment on, the space-traveling fixtures became known as “sputniks,” even though they bore only a vague resemblance to the historic artificial orbiters.

But just as the Space Age commenced with the first Sputnik blast off, with their ascent that night the Metropolitan Opera chandeliers launched many variations. Are they knockoffs, imitators or creative riffs on that original design? I’d say in this case they are the latter.

While some of the most lavish have crystal accents, or feature equally glittering rods crafted from Murano glass or Lucite, each has its own personality. And that’s true too with the more modestly priced versions from venues like West Elm or Pottery Barn, which catch the eye not so much with many glittering lights, but their reflective arrays of brass-plated spokes.

Yet distinct as they are, they share a common origin, unknown to but a few: an accidental splash of white paint.