April 19, 2020What springs to mind when you hear the phrase “design icon”? If you conjure up an image of Eero Saarinen’s 1956 Tulip chair — its curvaceous seat perfectly balanced on a slender pedestal — you’re far from alone. Saarinen’s lyrical design, now familiar to nearly everyone, even three-quarters of a century after its creation, quickly became a symbol of the jet age, a frequent prop in science fiction movies and a ubiquitous presence in conference rooms and breakfast nooks across the land. But no matter how many times you’ve seen the Tulip design — whether the chair or its companion table, both still produced by Knoll in a wide range of iterations — its power and impact never wane. Its brilliance is eternal.

We could stay up all night arguing about the definition of “design icon.” It’s a designation for which there are few objective criteria. One point of general agreement is that an icon is something produced in multiples.

“The Mona Lisa is an icon, but she became one through reproduction,” points out Glenn Adamson, an independent curator of craft, design and contemporary art. “Iconic designs are generally items that have been produced in large enough quantities to gain notoriety,” says Dexter Hutchison, whose Los Angeles store, Automaton, is a repository of early-production pieces from Herman Miller, Knoll and Fritz Hansen, among the mightiest icon makers of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Certain outstanding designs have such stellar quality they’ve endured for decades as bona fide cultural treasures, still being manufactured, in many cases, by the same venerable companies that shepherded them into being. Some works come immediately to mind as contenders for any short list.

One is Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s 1929 leather-and-steel Barcelona chair, so timeless that “most folks think it’s a contemporary design,” says Jesse Tzarax, of Danish Modern LA. (In nine short years, it will officially be an antique.)

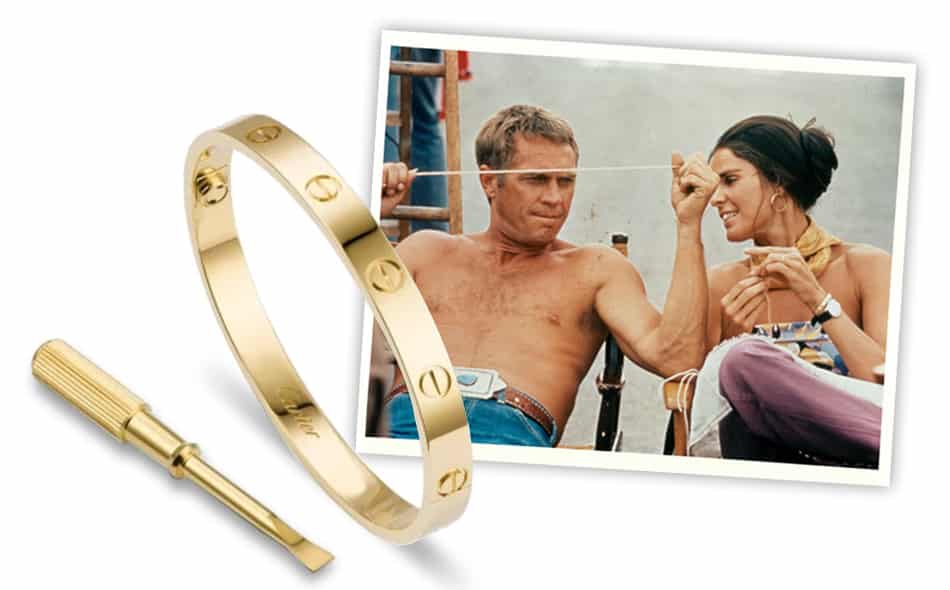

But icons can be found in all realms of the decorative arts, from Cartier’s slender Love bracelet, beloved for its simplicity since the 1970s, and Hermès’s Kelly bag, iconic on both design and pop culture levels, to the Castiglioni brothers’ 1962 Arco lamp, a masterpiece of functional minimalism still manufactured by the Italian company FLOS.

Maybe it’s no coincidence that so many of the pieces we consider iconic today hail from the decades immediately before and after World War II. We inhabit tumultuous times for sure; so did people in the middle of the 20th century. The modern age had only just roared into being when the planet was ravaged by war, soon to rise from the ashes with a dramatically different world order in place.

Furniture created in those turbulent years, from the 1930s through the ’60s, when functionality took on a sleek, pared-down new style, captured the zeitgeist. A raft of designs in new materials, with new forms, produced by American, Scandinavian, Italian and Brazilian companies, among others, combined the soberness of the war years with the cautious optimism of the period that followed. They struck just the right note then, and they continue to strike it now.

Singling out the iconic designs from the crowded pantheon of celebrated and seminal objects is a challenging task. For some people, few objects rise to true icon status. John Birch, of Sagaponack, New York’s WYETH, oversees a gallery that is a treasure trove of high-end vintage modern items, but he zeroes in on one seat in particular: Hans Wegner’s elemental teak Round chair of 1949–50, still produced today by Danish maker PP Møbler.

“It exemplifies an icon. It’s Design 101,” Birch says. “It’s the perfect chair, so obvious and yet not overexposed.” The supremely elegant form and construction of Wegner’s much-labored-over version of a classic Chinese chair led his contemporaries, including Finn Juhl and other Danish design luminaries, to designate it “the chair.”

Curators set up a larger tent. Adamson reminds us to leave room for contemporary practitioners in our zeal for anointing icons. “There’s merit to expanding the canon,” he says, calling out the amorphous work of millennial sculptor and furniture designer Misha Kahn at Friedman Benda and the new pieces in plywood shown recently at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, such as the Edie stool by David and Joni Steiner for the British company Opendesk and the Loop chair by the Danish designer Claus Breinholt.

Coleman Gutshall, president of Be Original Americas, makes a case for the icons of former times as springboards to designs of the future. Be Original Americas, founded in 2012 to advocate for the value of original design, partners with such flagship furniture producers as Vitra, FLOS, Alessi and Ligne Roset to support newer makers in prototyping, developing and manufacturing quality products.

“The best designs of the past have proved worthy, which is why they are icons,” Gutshall says. “But today’s designers are creating for dramatically different societies, and there are new materials and technologies to explore.” He notes in particular the Italian company Magis, whose spool-like Spun chair is sold by Herman Miller, and Nani Marquina, a designer originally from Barcelona whose captivating carpets are distributed worldwide under the brand Nanimarquina. Gutshall also sees potential icons in the pieces of the French brothers Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec for Vitra and FLOS, as well as the wide-ranging work of the Swedish group Claesson Koivisto Rune.

In addition, he cites emerging talents from new design hotspots, such as sub-Saharan Africa, where Chrissa Amuah and Alice Asafu-Adjaye founded Africa by Design to represent 30 designers from seven nations; and El Salvador, home to Harry and Claudia Washington, whose furniture designs are updated extensions of classic modernist principles.

Of course, the mid-century modern period doesn’t mark the starting point for design icons. When we cast an eye back a century or more, German Biedermeier and American Shaker furniture, with their presciently simple lines, stand out as landmarks on the road to modernism, and nothing is a more beloved cultural touchstone than a leaded-glass Dogwood or Dragonfly lamp from the turn-of-the-century Tiffany Studios.

Nor do icons have to be anything more than utilitarian. The humble lightweight aluminum Navy chair, a 1944 American industrial design still manufactured in Hanover, Pennsylvania, by Emeco, is so supremely functional that it remains ubiquitous today in homes, offices and restaurants.

Denmark has been a mother lode of ageless design. A powerhouse postwar industry developed there, largely based on an American audience’s embrace of beautifully crafted, sober but lyrical furniture and lighting. Arne Jacobsen’s free-form yet rigorous Series 7 stacking chair, designed in 1957 and in continuous production at Fritz Hansen, is quite possibly history’s best-selling seating. Poul Henningsen’s 1958 Artichoke lamp, both organic and futuristic and still made today by Louis Poulsen, has long been the V&A’s choice for its public spaces. Verner Panton’s all-one-piece plastic stacking chair of 1959, known as the Panton chair and now produced by Vitra, showed that “modernism doesn’t have to come in black or white,” says Murray Moss, who pioneered good design in retail at his eponymous New York gallery in the 1990s and now does the same through Mossbureau, which offers design counsel to museums. Tzarax gives a shout-out to Arne Vodder’s credenzas and Nanna Ditzel’s barrel chairs — not in current production but available in vintage versions — as examples of Danish furnishings impeccably designed for maximum comfort and ease of use.

The Americans have been no slouches either. Think of the great swoop of a Vladimir Kagan Serpentine sofa, which says “fifties” as surely as a Chevy Bel Air but is still much-beloved today, and of course, seating and case pieces by Charles and Ray Eames and George Nelson, whose designs for office furniture were avant-garde in the 1950s and ’60s but have since been widely welcomed in homes across the world.

When something is given icon status, “It can be like TSA preboarding, a vetting shortcut to making one’s own decision,” says Moss. One popular understanding of the term “design icon” is, in Moss’s words, “an uber-representative symbol of whatever category it’s in” — a criterion that can be applied to objects of any period, from the decorative arts of centuries past to Marcel Wanders’s Knotted chair of tied cords, which is found in major museums and emblematic of the 1990s flowering of innovative Dutch design.

Ultimately, says Moss, our notions of iconicity are fluid, changing over time. “Some people want the Georgian candelabra that is the most famous, the most recognized, the one that says it all. That’s fine, but it’s more interesting to remember that that is an attribution we give it today.”

Considering the enormous breadth and depth of the decorative arts, whether vintage or contemporary, and the ever-expanding roster of designers whose work resourceful 1stdibs dealers are continually bringing to light, the discerning collectors’ field of exploration is wide open. The supply of inventive, even brilliant, design objects abounds, even while, as we speak, new artists and makers are pushing the boundaries of what constitutes a design icon.