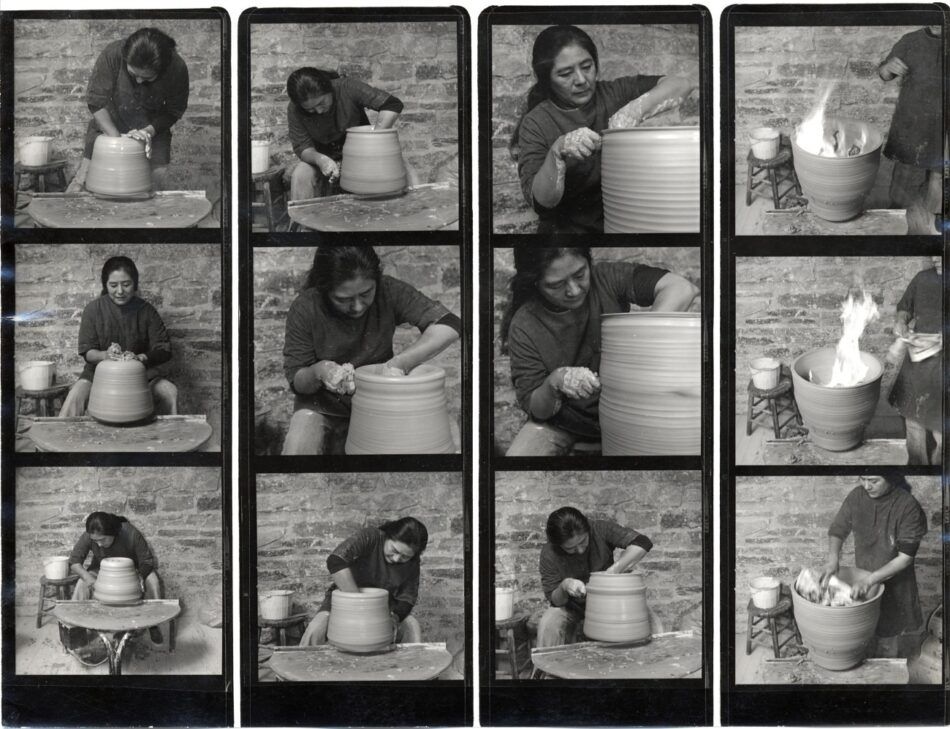

Just this year, there have been major museum exhibitions in Stockholm, New York, Boston and Bentonville, Arkansas, centering on the pottery of Toshiko Takaezu.

The scale and importance of these shows dedicated to the Hawaiian-born ceramist got us thinking about how bold and brave Takaezu was for throwing clay in unexpected ways during a time when ceramics was generally ridiculed as mere craft by the art-world condescendi.

Looking to folk, indigenous and Japanese wabi sabi traditions, Takaezu was part of a small group of mid-20th-century American artists who embraced imperfection in their pottery.

This would serve as a counterpoint to the smooth lines and overall slickness of modern and postmodern movements like Bauhaus, constructivism, minimalism, Op art and Pop art.

Here, we spotlight five artists, starting with Takaezu, who innovated chunky, funky ceramics in the mid-century and beyond.

Toshiko Takaezu

Born on the Big Island of Hawaii to Okinawan immigrants, Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011) merged Japanese ceramic traditions with modernist élan. Her famous “closed-form” creations — like the wheel-thrown Moon orbs and human-scale Star Series vessels — are sealed shut and decorated with free-flowing glazes. They feel simultaneously ancient and avant-garde, especially the ones that rattle, thanks to the clay fragments or beads contained within them.

“I see her closed-form vessels as contemplations on the ancient Eastern concept of emptiness that forms the foundation of Taoism and permeates the core practice of Zen Buddhism,” says Tony Shubart, owner of TISHU gallery, in Atlanta. “The empty space enclosed in her vessels, sometimes with an auditory cue from the sound of the rattle, reminds us of the importance of the absence. After all, the emptiness inside the wall makes a vessel as much as the wall itself.”

Even after moving to the mainland, where she attended the Cranbrook College of Art and later taught at Princeton, Takaezu infused her works with Hawaiian volcanic ash, baking a bit of home into their earthenware walls. Whether outsize installations or handheld teabowls, her ceramics always reflect the natural world.

Peter Voulkos

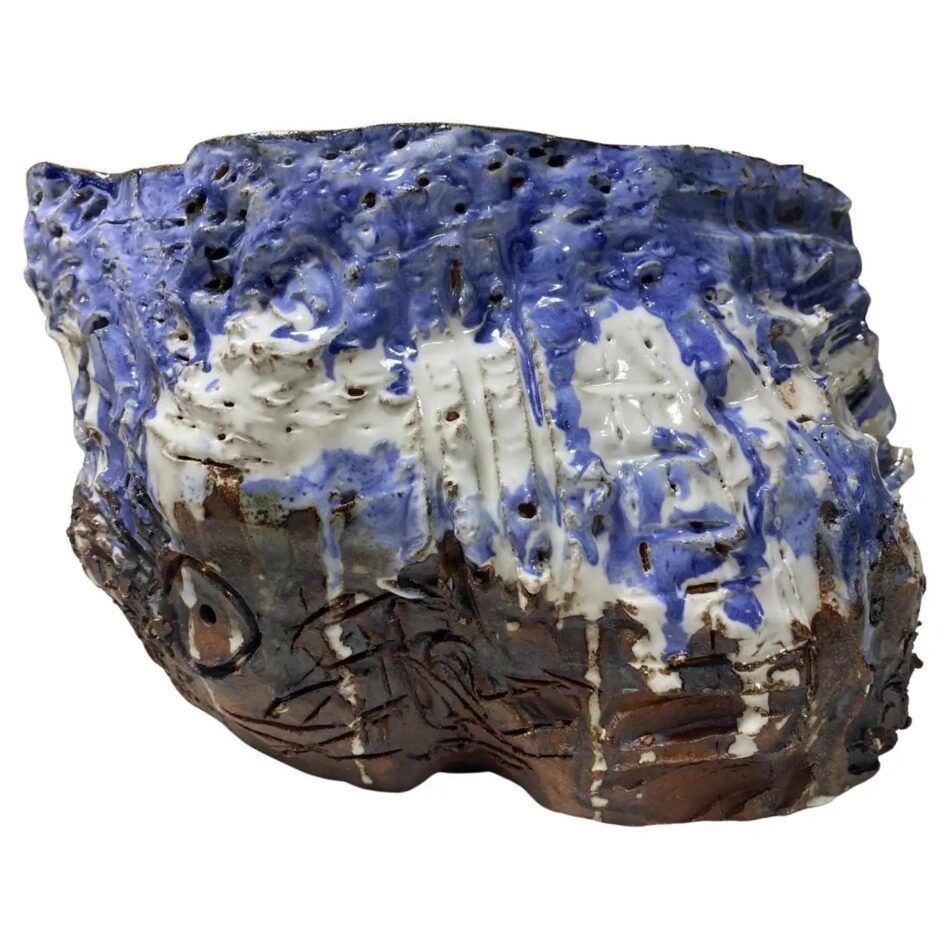

Originally from Bozeman, Montana, Peter Voulkos (1924–2002), the bad boy of American ceramics, kicked clay off its pedestal in the 1950s. With their thick slabs, drippy epoxy paint and contorted features, Voulkos’s expressionistic sculptures look like they were made by a dextrous silverback gorilla let loose in a ceramics studio. Voulkos founded the ceramics department at the Los Angeles County Art Institute (later Otis College of Art and Design), influencing generations of American potters and sculptors.

“Although initially working with traditional utilitarian forms, Voulkos revolutionized pottery by focusing on imperfection and deconstruction, building massive muscular pieces and devising sculptural forms with a fervent, energetic spontaneity,” says Greg Nielson, of Dwell Floor Five, in Studio City, California. “A very charismatic figure — about as close to a rebellious rock star as one can find in the medium — Voulkos is fondly remembered as an artist who violated every rule and reinvented the modern ceramic fine art form.”

His anti-pretty, anti-functional pieces freed ceramics from craft-world constraints and redefined it as a medium for making cutting-edge sculpture. Decades later, contemporary artist Sterling Ruby would channel Voulkos by smashing his past creations together into hulking mounds of shattered clay vessels.

Paul Soldner

After studying under Voulkos at the Los Angeles County Art Institute, Denver native Paul Soldner (1921–2011) became a pottery professor there in the 1960s, when the revolutionary California Clay Movement took root.

Soldner pioneered American-style raku firing methods, experimental updates of the centuries-old Japanese process, which involve pulling red-hot sculptures out of the kiln to be bathed in smoke or dipped in cold water, resulting in beautifully frazzled glazes. “These new firing and post-firing reduction methods often led to spontaneous, unpredictable and quite wonderful results,” Nielson notes.

Soldner’s raku vases, for instance, with their charred surfaces, seem to smile humbly through the scars of their past adversity.

Stan Bitters

Hailing from Fresno, self-proclaimed “old hippie” Stan Bitters (b. 1936) studied under Voulkos — and his funky, fractured style shows it. Bitters constructed rough assemblages of clay slabs and spoked wheels into massive murals and tall totems, upsizing 1960s ceramics to an architectural scale.

“Known for his Abstract Expressionist style, Bitters is a steadfast champion of environmental ceramics — the melding of natural, organic clay forms, sculptures and architectural elements into urban spaces to complement, transform and elevate their surroundings,” Nielson says.

With their sputtery glazes and graffiti-esque glyphs, Bitters’s works exude raw, countercultural energy.

Janet Rothwoman

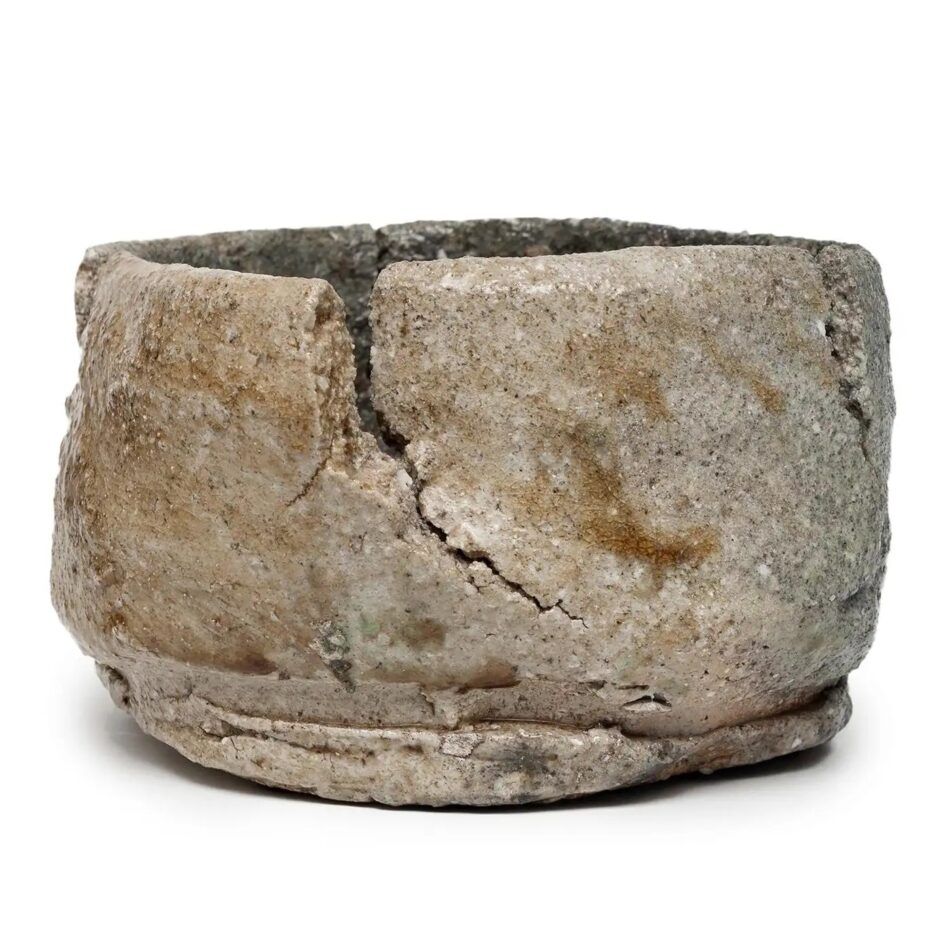

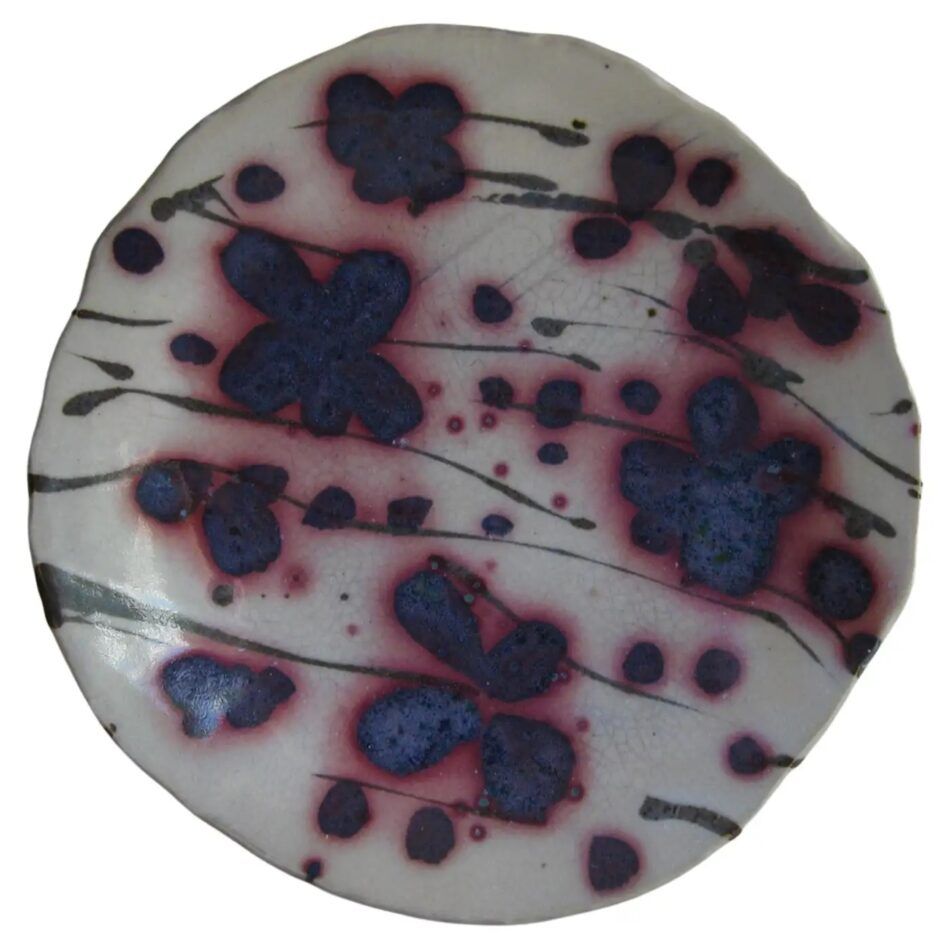

While the guys got more credit, New York City–born Janet Rothwoman (1920–2008), married to fellow ceramist Jerry Rothman, was among the vanguard of artists upending traditional pottery in California. Using wax, clay and found objects, she hand-built earthy sculptures with a prehistoric vibe, and her primordial ceramics still feel vibrantly contemporary today.

“Janet Rothwoman’s studio-pottery style and form were unique for a female artist during this time,” says Jonny Guilmet, owner of design/one gallery, in San Diego. “She was heavily influenced by her husband, Jerry Rothman, and the Otis College movement. Janet’s work was way ahead of her time.”

Eventually, Rothwoman broke the rules of the rule breakers by making platters festooned with folksy farm animals. These functional and figurative works brought the medium full circle.