A Temple St. Clair oval rock-crystal amulet with diamonds and 18-karat gold.

The oldest form of jewelry is said to be amulet jewelry. Our earliest ancestors ascribed meaning — and magic — to feathers, bones, stones and even tree bark. They wore or carried these “amulets” for protection or to enhance their strength, courage or sexual attraction. Over time, these were replaced with symbolic objects: small replicas of animals, plants and, later, gods.

Ancient Greek gold swivel ring with rock-crystal scarab, ca. 500 B.C. Offered by Romanov Russia

For the Egyptians, there was no more potent protection than the image of the scarab, otherwise known as the dung beetle. They believed it was a male-only species that reproduced itself by depositing its seed in dung, which its babies then fed upon.

By turning waste to life, the scarab symbolized the god Khepri of the rising sun — “he who has come into being from nothing” — and hence both transformation and resurrection. So wondrous were the powers of the scarab that it became a popular part of amulet jewelry throughout the ancient Mediterranean, as is demonstrated by this Greek signet ring (above), crafted circa 500 B.C.

Christian Dior by John Galliano Egyptian revival scarab necklace, 2004. Offered by Le 6 Rue Paradis

And the dung beetle continues to fascinate designers as a symbol even into our present day, with none other than John Galliano creating an Egyptian Revival necklace for Christian Dior’s Spring/Summer 2004 collection. In the center of the piece is an orange Lucite scarab.

Another captivating amulet motif among the Egyptians was the Wadjet, the eyeball of an ancient snake goddess, who protected the pharaoh, the land and all who wore her from the evil eye. It must be said that almost all ancient peoples believed that there were those among them who possessed the supernatural ability to cause harm through a malevolent gaze.

Another desert tribe, the Hebrews, had a very different concept of the amulet. A people of the book, forbidden from using graven images, they created theirs from texts and names and symbols. And so their amulets include the symbol Chai meaning “life” or Yah, one of the names of God, inscribed on a piece of parchment or silver as a pendant.

Diamond and white gold Star of David and chain. Offered by Helen Ringus Jewels

As for symbols, there is none more sacred or shielding in the Judaic faith than the two intersecting triangles deriving from the Shield of David, but today known as the Star of David. Once considered a rustic charm, it has evolved into one that can be both luxurious and fashionable.

Triangles have protective powers for many peoples of the Middle and Near East. Much more than decorative, this geometry prevalent in Berber and Turkic rugs is meant to be protective. Rugs are considered to be amulets in their own right, generating a defensive field within the home to ward off unseen evil.

Moroccan Judaic brass Hamsa pendant, 1920s. Offered by Mosaik

The Jews and Muslims share another talismanic symbol: a representation of a woman’s hand, known variously as the Hand of Miriam (the sister of Moses) or Fatima (the daughter of the prophet Mohammed). Among the Berber tribes it is called the Hamsa.

Whatever its name, it guards specifically against the evil eye. So “eye-catching” is the imagery that contemporary jewelers still draw upon the Hamsa when going after a boho look.

Left: Buddha Mama Hamsa ring, 21st century, offered by Provident Jewelry. Right: Amedeo Evil Eye cuff bracelet, 2017.

Italians to this day, especially in the south, remain wary of the evil eye, known in that country as the malocchio. Amulets to shield against it remain not only popular, but distinctly on trend.

Russian enameled-gold cross pendant, ca. 1890. Offered by Romanov Russia

Speaking of the Mediterranean region, the early Christians employed the crucifix not only as a symbol of faith but also protection. This 19th-century Russian version depicts Jesus rising above a skull and bones to emphasize his transfiguration.

Gem-encrusted jade Haldili amulet, ca. 1800. Offered by Kunsthandel Inez Stodel

In India, many amulets combine the symbolism of its two most prevalent faith: Hinduism and Islam. This piece of amulet jewelry, a pendant known as a Haldili, with its stylized representation of the flowering Tree of Life, represents the divine vital force both and is worn to protect the heart from grief and palpitations.

Hmong silver spirit-lock necklace, mid-20th century. Offered by the Golden Triangle

Perhaps some of the most intriguing amulets are those created by the Hmong of Southeast Asia, who believe that each individual has multiple souls that must be retained with the body if an individual is to have a healthy and prosperous life.

If a Hmong becomes ill, a shaman must perform a ceremony to retrieve her errant soul and once recovered, she must wear a “spirit lock” to ensure it doesn’t again escape. Over the course of a life, some Hmong end up wearing up to six of these magical locks. This striking silver collar features three of them.

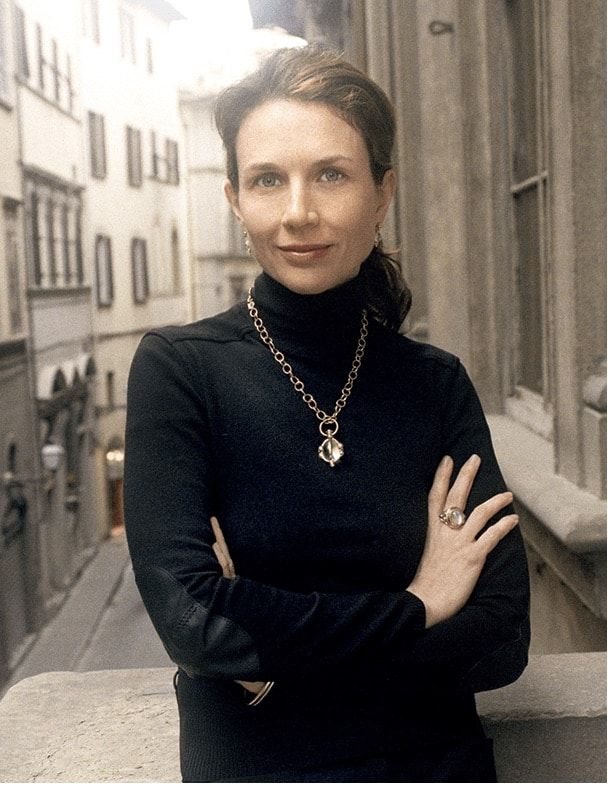

Jewelry designer Temple St. Clair in Florence. Photo courtesy of Temple St. Clair

Like primeval man, the jeweler Temple St. Clair believes that any adornment can be a power object, so long that it has special meaning to us. She should know. St. Clair began her storied design career — she’s the first contemporary woman jeweler to have her work included in the jewelry collection of the Louvre — by conceiving modern-day amulet jewelry.

A scholar of the Italian Renaissance before she turned her creative talents to precious adornments, St. Clair imbued her collection of rock-crystal orb pendants with the imagery and sensibilities of the Renaissance. The pieces, which have a modern sensibility while recalling an era when alchemy prevailed as the reigning science, are at once timeless and captivating.