“I grew up on Long Island,” says Howard Williams, furniture dealer and owner of High Style Deco, in New York City. “When I was 10 years old, my parents took me to Radio City Music Hall, and I was blown away.” The landmark 1891 theater’s Art Deco interiors dazzled Williams. As an adult, he began collecting exemplars of the style for himself.

His first career was selling art. “But the artists I was carrying were very mass-market and commercial, so I didn’t really believe in it,” Williams says. So, he indulged his passion for design. “I opened my furniture gallery in 2003. At first, it was all Art Deco. But now, I just collect what I like, which includes a lot of mid-century modern.”

Williams has a penchant for unusual finds and pieces that seem to straddle eras. He buys nothing that is broken and needs repair. He does reupholster, refinish, clean, polish and rewire, however, “to bring every piece back to its original condition,” he explains. “Being a neurotic perfectionist is great for that!”

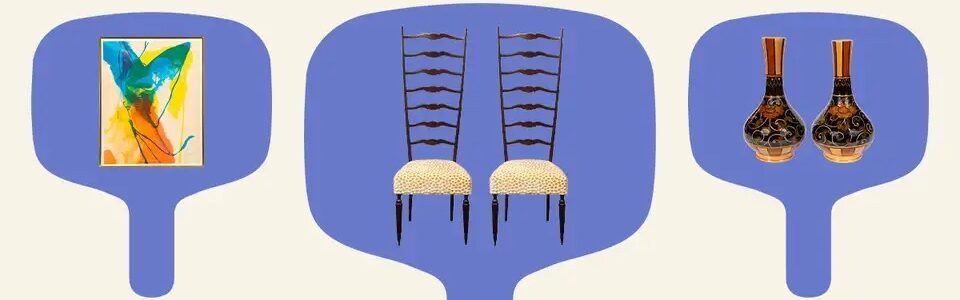

Williams is currently offering a curated selection of his vast inventory on 1stDibs Auctions. Here, he discusses just a few of the standout designs.

Grosfeld House End Tables

“If you grew up in the 1950s watching movies like Harriet Craig, with Joan Crawford, or The Women, you might realize that all those sets were decorated by Grosfeld House,” says Williams. Active from the 1930s to the 1970s, the famed New York furniture maker was particularly popular with Hollywood designers because of its use of unconventional forms and glitzy ornament, as well as luxury materials and finishes.

Characteristic of the firm’s work are these book-matched walnut end tables or nightstands, which sport extravagant gilded sunburst pulls. Made in the 1940s, they were designed by Lorin Jackson, whose creative direction arguably put Grosfeld House on the map. Jackson was liberal in his cross-referencing of styles. His work, says Williams, embodies “Hollywood glamor at its best — a touch of Hollywood Regency meets Art Deco meets streamlined design.”

Grosfeld House Occasional Chairs

Another favorite of Williams’s is a pair of circa 1945 Grosfeld House ebonized-walnut wing chairs, also designed by Lorin Jackson. The form, of course, is traditional. But Jackson lightened the profile by giving the wings here a slimmer silhouette and opening them up with latticework. Though wings are normally curved and upholstered, these “were a modern take,” Williams believes, “and very ahead of their time.”

The chairs also happen to be in perfect condition. But it’s the fanciful period mixing — their blend of Art Deco styling (the channel tufting and rounded back), mid-century-modern twists (the streamlined arms and lattice) and neoclassical elements (the klismos legs) — that hit the sweet spot for Williams.

Aldo Tura Bar Cart

Williams concedes that this nautical-themed bar cart by renowned Italian furniture designer Aldo Tura is “quirky,” or “even borderline kitsch.” Indeed, a closer look reveals that the diagonal lines connecting the shelves and the wheels are stylized lobster claws. The wheels themselves look like they came from ships’ helms, and the brass handles on the trays look suspiciously like scallop shells.

What pulls this 1970s design back from its perilous position on the brink of kitsch are the construction and materials. Tura was known as “the master of parchment.” On this cart, he indulged his love of the material by wrapping the frame and trays in supple goatskin. The combination of parchment, brass and glass imparts a touch of Tura chic to what is a fundamentally whimsical object.

Gaetano Sciolari Chandelier

This dramatic piece screams 1970s, when Italian lighting designer Gaetano Sciolari was at the height of his powers. “It’s like a hanging sculpture, but it’s a chandelier,” Williams observes. Sciolari was famous for mixing shiny and matte materials and often employed glass bottle forms in his lighting, which he produced in his own shop for his family business and, in the 1950s, for Stilnovo. Imported to the U.S. by Lightolier and Progress Lighting, his designs were an instant sensation in the States.

So much so, in fact, that from the 1960s through the 1980s, TV viewers — especially those whose taste tended toward futuristic programs — might glimpse his pieces on many sets. Today, his designs are highly collectible. This one, featuring six tiers of tubular polished aluminum forms with cutouts revealing 24 mercury bulbs, looks like it belongs at a disco, along with Paco Rabanne space curtains and women in sequined miniskirts.

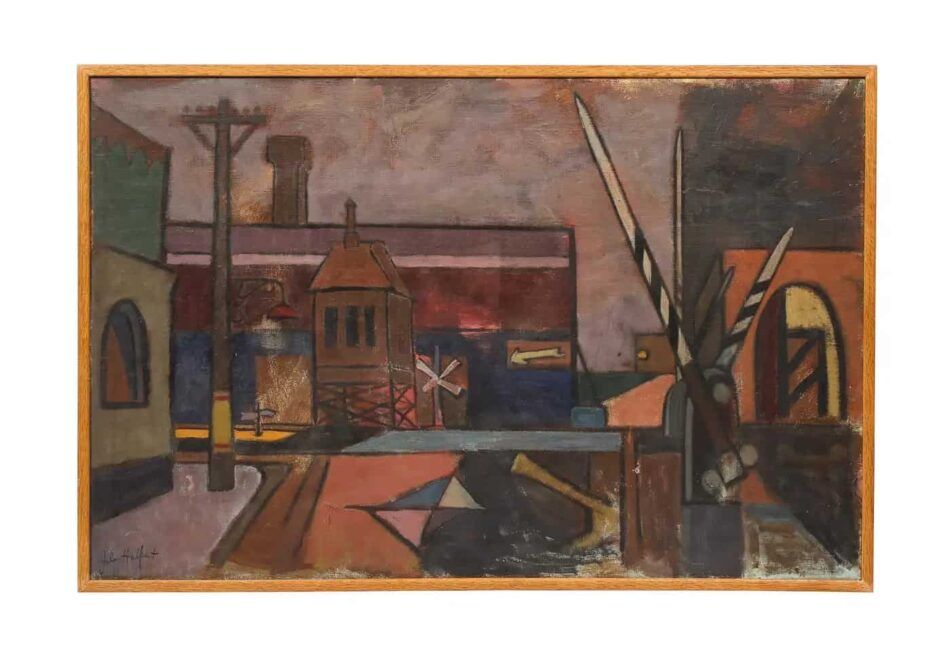

Rail Crossing: Middletown, NY, by Jules Halfant

The American painter and printmaker Jules Halfant had an interesting career. During the Great Depression, he was one of the WPA artists in the New Deal’s Federal Art Project, mingling with the likes of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Milton Avery and Stuart Davis. The influence of the last can be seen in this 1941 oil on linen. “There are telephone wires, old-fashioned street lights, a railroad crossing — a lot going on,” says Williams. “But it’s all done in a cleaner, modern, abstract way. It’s a great use of color, rich but muted.”

Halfant plied his flat, foreshortened perspective and mastery of hues in other formats too. From 1953 to 1988, he created album-cover graphics for musicians as diverse as Joan Baez, Country Joe & the Fish, Buffy Sainte-Marie and P.D.Q. Bach. He also designed the poster for Bob Dylan’s 1963 Town Hall concert. Simultaneously, he was painting scenes with Jewish and biblical themes.

Crystal Kinkeldey Chandelier

Williams unearthed this hexagonal chandelier in the Sablon Antiques Market of Brussels. It was perhaps not coincidental that it landed there, as its geometry, polished chrome and molded crystal would look right at home in Josef Hoffmann’s Palais Stoclet, in the city’s center. Indeed, says Williams, “it was made after World War II, but it feels like it could be Wiener Werkstätte or even Art Deco.”

Because it was made by the German firm Kinkeldey, active in the 1960s and ’70s, he knows it could not have been either. It also uses smoked glass, which became popular in the mid-20th century. That glass diffuses the glare of six candelabra-style bulbs, while sparkling crystal hand cut with X-shaped facets further modulates the luminosity, casting a mellow but glamorous glow.

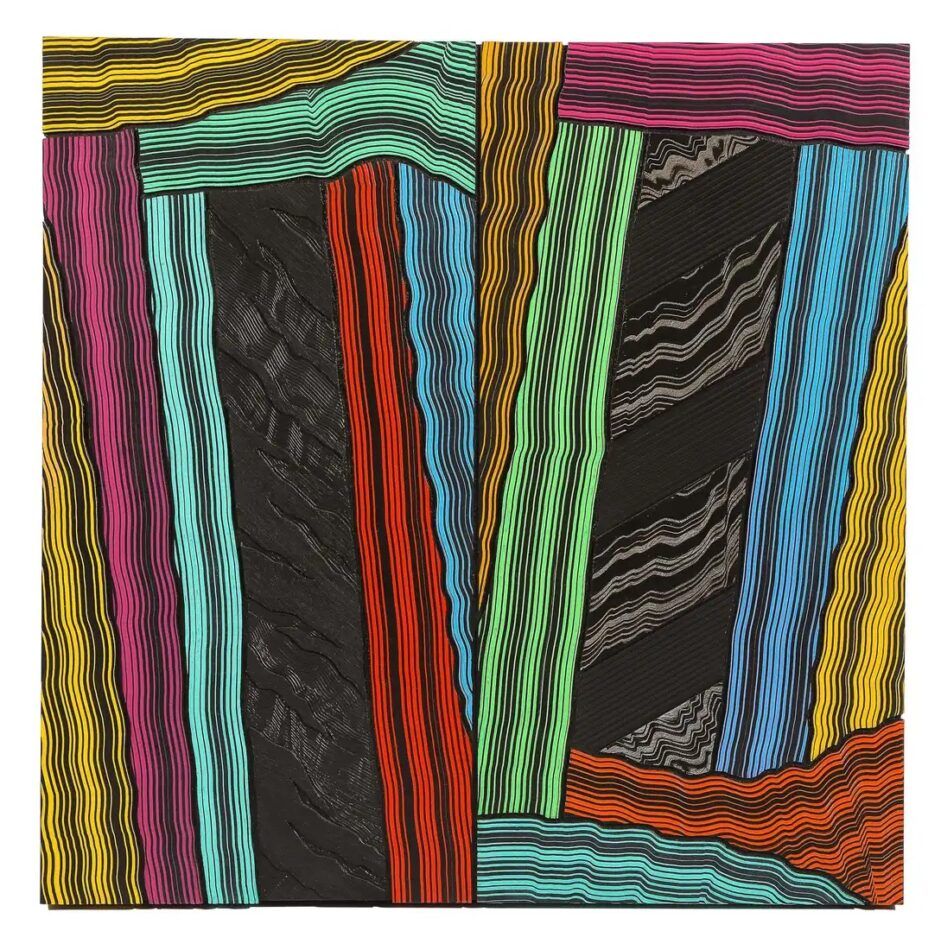

Indra, by Jim DeFrance

Williams acquired this striking acrylic-on-birch work by West Coast artist Jim DeFrance from a friend. Before making the initial purchase, the friend “was debating between this painting and a Basquiat,” says Williams. “He did not choose well.” True, the Basquiat has no doubt increased exponentially in value. But Indra, as the 1987 work is titled — presumably after the king of the gods in the Hindu tradition — has undeniable charms. “You can decorate a whole room around it,” says Williams. “It definitely pops, and for not a lot of money.”

Although the piece is unique and not easily pigeonholed into a particular genre, it suggests shades of Roy Lichtenstein, as well as geometric abstraction. The thick brushstrokes in bright colors against a black ground recall the cartoon-cool paintings of Lichtenstein, albeit in a much more hallucinogenic way. And at 36 square inches, it has no problem dominating a wall.

Adrian Pearsall Chair

Although made in the 1970s, this chair by Adrian Pearsall doesn’t stray too far from the prevailing aesthetic of the 1950s, the decade in which Pearsall came of age as a designer and architect. He and his brother established Craft Associates to manufacture his designs in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in 1952, two years after he graduated from the University of Illinois.

This piece, says Williams, “is an iconic design, documented in the Craft Associates catalogue.” Identified as item no. 2051-C, it displays Pearsall’s predilection for button adornments. Even as the style at the time of its manufacture was shifting to black lacquer and angularity, Pearsall persevered in his Jetson-like aesthetic, turning out lithesome upholstered forms resting, for the most part, on affordable polished, molded plywood bases with tapered contours. Here, however, the frame that cradles the seat is walnut.