When a jewel makes the news for commanding an astronomical seven figures at auction, it usually centers on a rare gemstone, such as a blue, pink or green diamond. Sometimes, a piece hits those heights because it’s beautiful and has a special provenance. But every once in a while, it’s a jewel’s brilliant design that launches it into the million-dollar stratosphere.

On December 9, 2020, at Sotheby’s New York, a circa 1965 Van Cleef & Arpels Mystery Set sapphire and diamond flower brooch sold for $1,109,000. The astonishing sum was almost nine times the lot’s $120,000 high estimate.

The piece had neither celebrity provenance nor a high-carat center stone. The only discernible reasons for its price were its overall quality and the desire of several clients to own an iconic Mystery Set design.

Cartier’s Art Deco Tutti Frutti bracelets, set with carved emeralds, rubies and diamonds, have routinely sold for more than $1 million at auction since 2014. That year, an example belonging to Evelyn Lauder brought in just over $2 million at Sotheby’s New York.

At least one of Bulgari’s late-1960s enamel and diamond Serpenti watches has fetched more than $1 million since 2013. That’s when these sinuous timepieces slid into the consciousness of the jewelry-loving public, thanks in part to the publication of Bulgari: Serpenti Collection (Assouline), by yours truly.

Now, another style has joined this exclusive club.

To be clear, it’s not the flower motif that’s iconic. It’s the Mystery Setting, a technique Van Cleef pioneered in the early 1930s.

The Van Cleef & Arpels Mystery Setting Technique

On December 2, 1933, the French firm received a patent for its brainchild, titled simply “method for setting precious stones.” A few years later, as the house began rolling out designs with the new look, it became known as the Serti Mystérieux or Mystery Setting.

An invisible setting had been used for flat surfaces before, but it was Van Cleef & Arpels that made it possible for three-dimensional pieces.

What makes the Mystery Setting so special is the way the mounting is completely hidden under the gems. Rather than using traditional prongs, Van Cleef’s technique employs undetectable gold or platinum rails to mount each faceted stone. The use of the rails results in the signature appearance of floating gems.

Despite the patent, other jewelers did and still do copy the Mystery Setting technique, but no one employs it with as much style as Van Cleef & Arpels.

According to French jewelry historian Vincent Meylan, Van Cleef improved on a method others had tried to perfect since at least the Renaissance.

“Artisan jewelers have always worked towards an ideal of highlighting the precious stones by minimizing the metal structure, the setting that holds them next to each other on necklaces, pins or earrings,” he writes in his book Treasure Hunt: A Century of Emeralds (VM Publications).

Van Cleef’s innovation involves cutting all the little stones in a design so that they fit together like puzzle pieces and then making grooves on two sides of each stone. “It’s a delicate process for rubies and sapphires, which are not as hard as diamonds, but it’s a miracle for the emerald, which is a much more fragile stone,” writes Meylan. The canals in the gems are used to slide them onto a setting that’s akin to railroad tracks. None of the metal remains visible, as it does in many common settings.

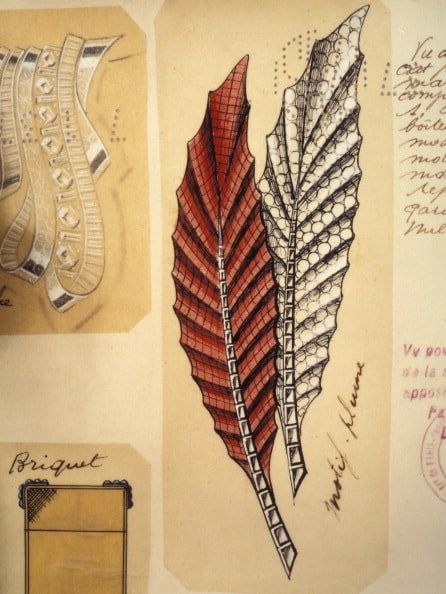

The most dazzling Mystery Set jewels have naturalistic curves and a sculptural quality. One famous early example is a Van Cleef brooch in the form of a double quill (or holly leaves), purchased in 1936 by King Edward VIII as a Christmas present for his future wife, the American divorcée Wallis Simpson. The oversize piece features two leaves — one glittering with diamonds and the other undulating with Mystery Set rubies.

In 1937, Van Cleef & Arpels demonstrated its mastery of the technique in a peony brooch. The piece features diamond leaves nestling a lush Mystery Set ruby bloom whose petals curve and turn at various angles. Part of the Van Cleef & Arpels Collection of historical pieces, it has been displayed in museum exhibitions around the world.

The house has continued to make a very limited number of Mystery Set jewels over the decades.

Some have been special commissions, such as Eva Perón’s 1940s Argentinean flag brooch, its blue stripes rendered in Mystery Set sapphires. Elizabeth Taylor owned a pair of diamond and sapphire earrings with teardrop Mystery Set sapphire pendants created around 1985.

Although the Mystery Setting has long been part of the Van Cleef & Arpels repertoire, pieces exhibiting the technique have always been relatively rare on the market.

But as these jewels keep breaking the million-dollar barrier at auction, those sales might inspire owners of similar pieces to pull them out of the vault and put them on the block. And the Mystery Setting will ascend even higher in the ranks of jewelry legends.