June 28, 2020Picture a showhouse with no bad spaces — no powder rooms squeezed under the stair, no libraries riddled with unattractive soffits, no cramped butler’s pantries sandwiched between kitchens and dark hallways like an afterthought. Instead, every room is exceptional, the product of a brilliant, revolutionary design mind. Where is this magnificent manse?

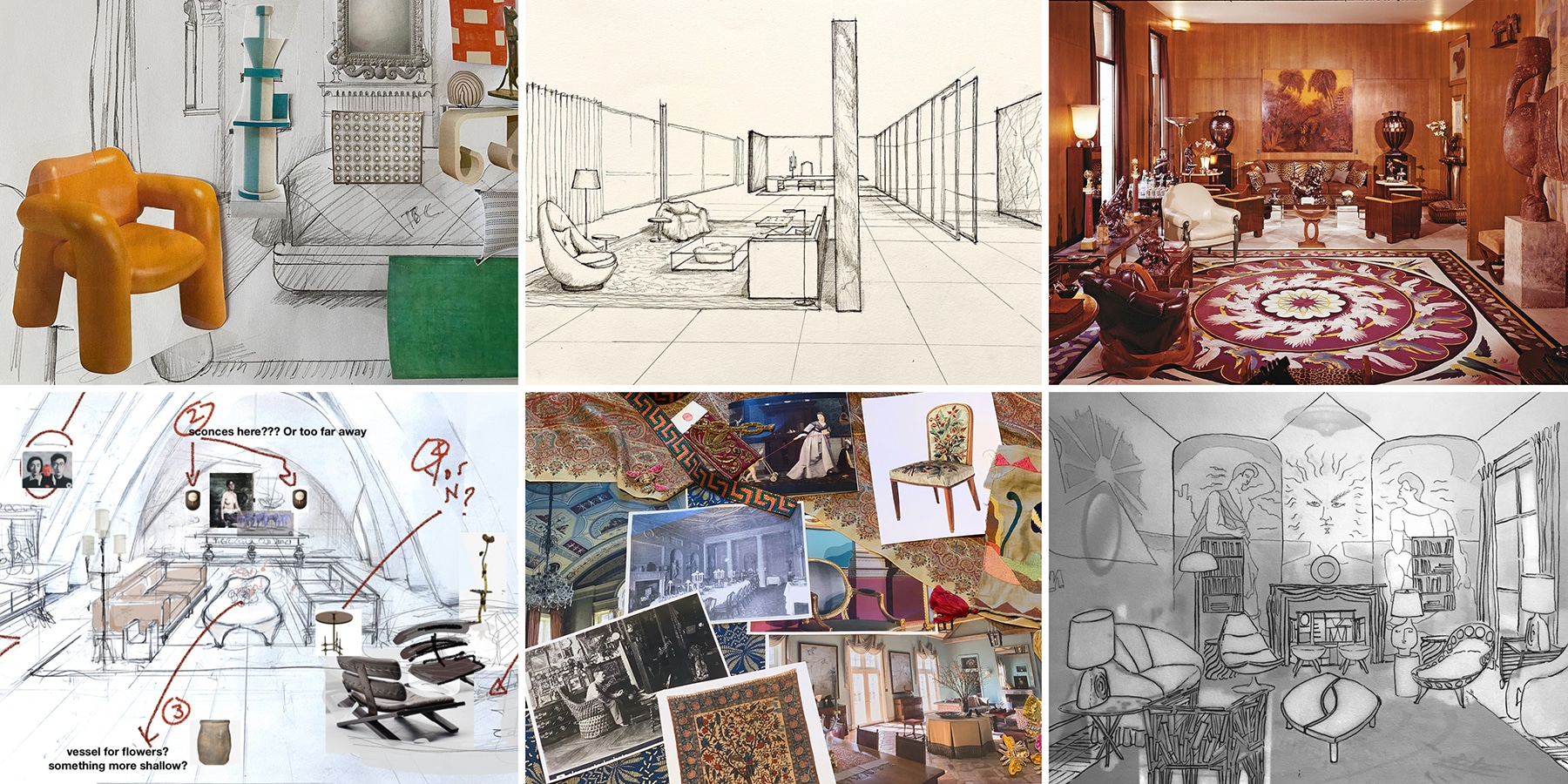

In virtual reality, like so much else these days. Right now, nothing seems normal in our world. So, we decided to take a most unconventional approach to the traditional showhouse model by asking a heady group of designers to each select an iconic historic room that has fascinated them for years, then bravely and boldly redesign it for today by availing themselves of the limitless treasures on 1stDibs. Here are the show-stopping results of the first-ever 1stDibs Virtual Showhouse.

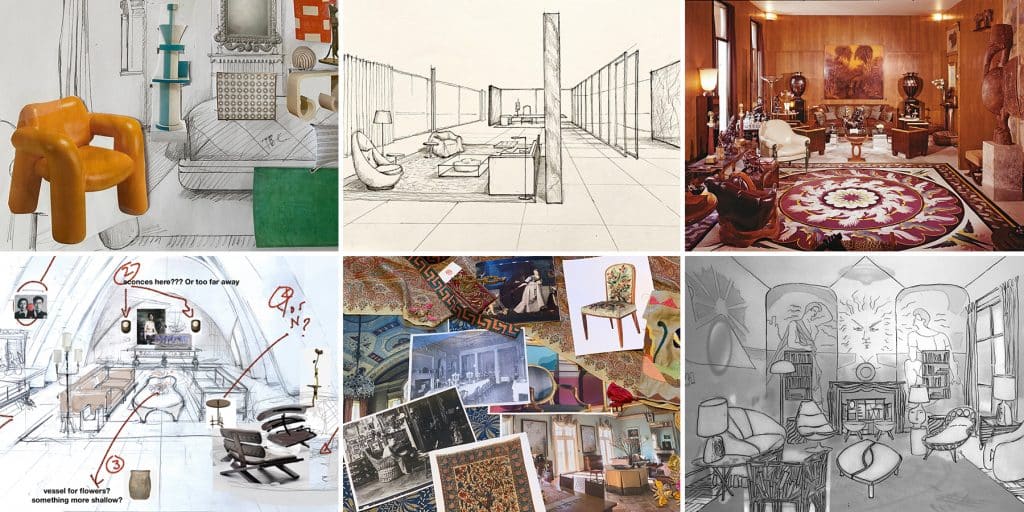

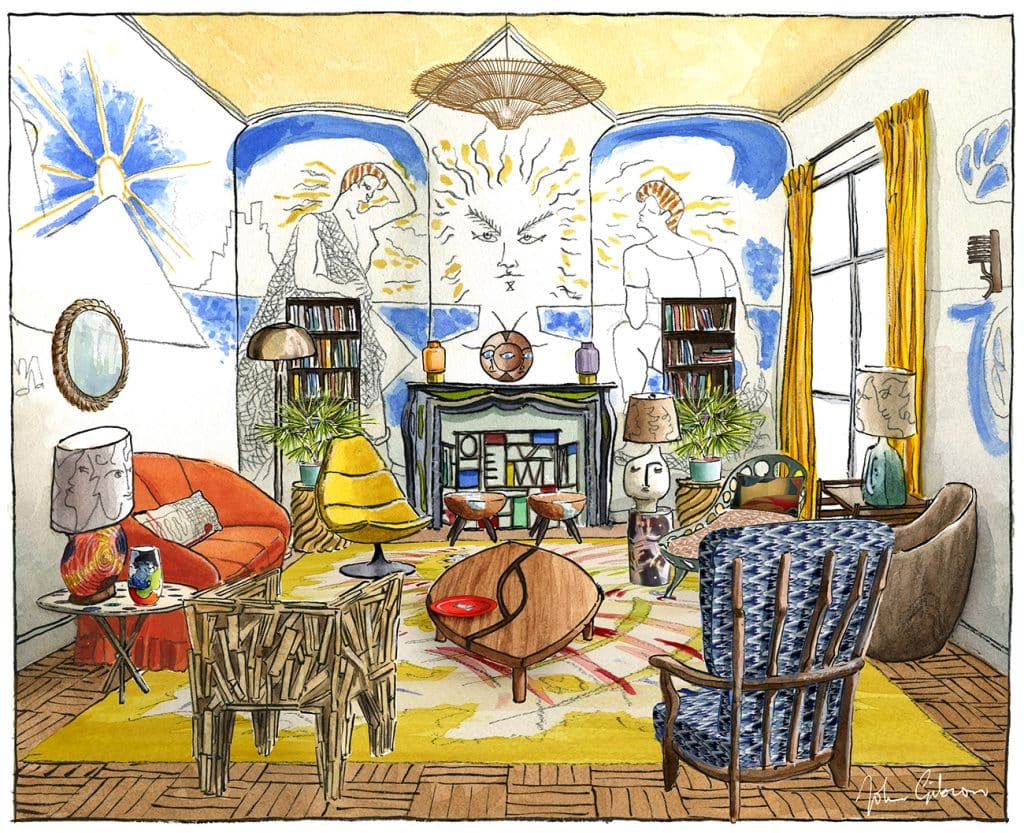

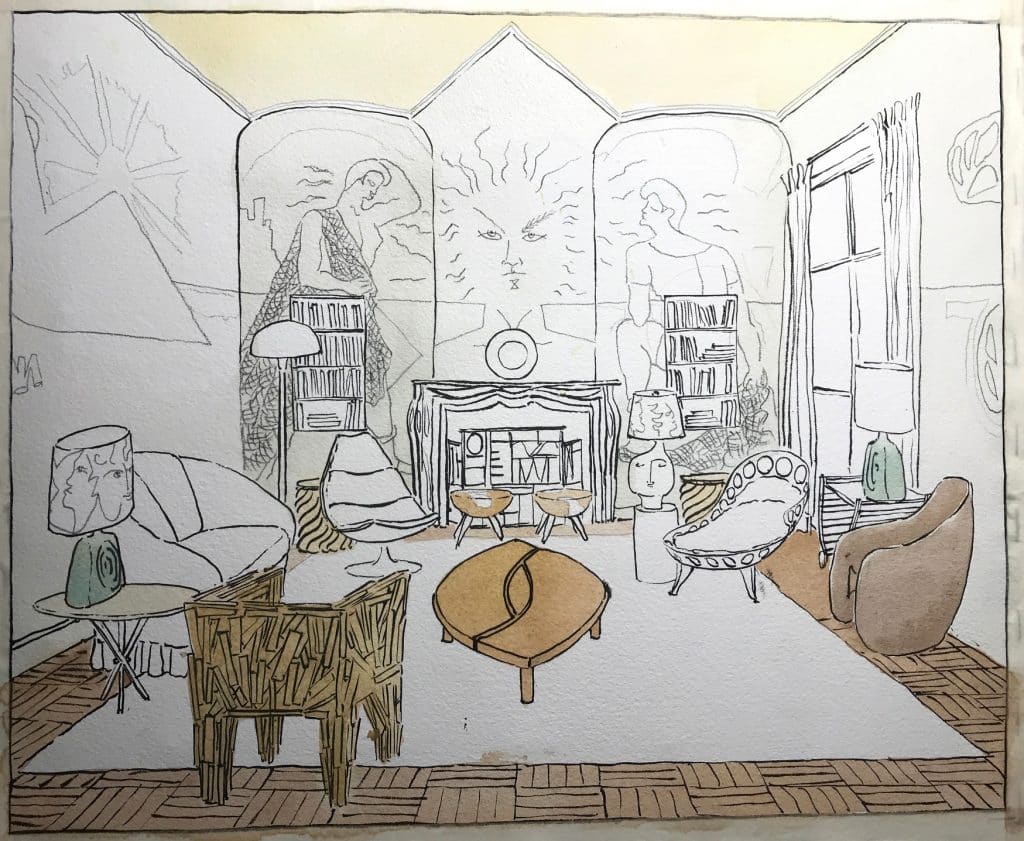

Living Room, Villa Santo Sospir, Saint-Jean Cap-Ferrat

Creator: Madeleine Castaing and Jean Cocteau • Built: Shortly after World War II; Cocteau murals painted summer, 1950

REIMAGINED BY: SARA BENGUR INTERIORS

In his film about Villa Santo Sospir, Jean Cocteau says of the Côte d’Azur home, belonging to socialite Francine Weisweiller, “We have tried to defeat the destructive spirit of our time. We have ornamented the surfaces which men dream to demolish. Perhaps the love of our work will protect it from bombs.” This description, considered within the context of our own time, deeply resonated with New York designer Sara Bengur, who chose to reimagine the villa’s living room, designed by Madeleine Castaing and “tattooed” by Cocteau with murals of Apollo and local life. “What we’re all going through,” she explains, “the sadness, the tension the rage — we all need these pockets of fantasy and lightness and creativity.”

The space was already a rich “pocket” of all those elements, but the Turkish-American designer tapped her love of color (and her peripatetic upbringing) to ramp up the sense of artful escape. “It was a fascinating time in the South of France,” Bengur observes, “a moment that was very relaxed and very humble in a way, when a lot of artists went there to retreat and create.” Her first find for the room was a suitably painterly French Art Deco rug. She then added pieces that nodded to the villa’s heyday, mixing them with contemporary furniture and objects.

Among the items evocative of the period are a 1936 Giò Ponti sofa, a 1960 sculptural Guillerme et Chambron chair, a circa 1945 Gerrit Rietveld tea cart and 1950s table lamps by Marcello Fantoni. Subtle references to the fishing village of Villefranche, as well as to Castaing’s original interiors, appear in a rope-framed mirror and rattan, wicker and bamboo pieces, such as a ceiling fixture, a sconce and Vivai del Sud side tables. The era’s Surrealist sensibility makes cameo appearances in a Pierre Chapo coffee table (referencing a Cocteau plate adorned with eyes on the mantel) and works by Fornasetti. The Campana Brothers’ Favela chair, a Drillium chaise by Robert Remer and Geoffrey Harcourt’s mustard-yellow High chair bring everything into the now.

“It’s another world, in which it’s essential to forget the one where you live,” Cocteau said of Santo Sospir. Bengur ensures that it remains so.

Wrought-iron fireplace screen, late 20th century, offered by Kirby Antiques; Marcello Fantoni multicolor table lamp, 1950s, offered by rewire; Pierre Chapo T22 coffee table, 1975, offered by Hep Galerie; Art Deco rug, early 20th century, offered by Mansour; Fernando and Humberto Campana Favela armchair, 2016, offered by MINIMA; Piero Fornasetti Flowers gueridon, 1970, offered by Galerie Stanislas; Raina Lee vase, new, offered by Sight Unseen; Giò Ponti sofa, 1936, offered by Vintage Domus SRL; Schumacher Artigianale pillow, new; Adrien Audoux and Frida Minet mirror, 1960, offered by Majolicadream; Mid-century modern floor lamp, 1960s, offered by JosephDesign; Vivai del Sud nightstands, 1970s, offered by Goldwood Interiors; Geoffrey Harcourt high-back chair by Artifort, 1967, new reissue; Hans-Agne Jakobsson model L-95 candlesticks, 1950s, offered by Studio Schalling; Wood-and-resin side tables, 1970s, offered by Pegaso Gallery Design; Dalo lamp base, new, offered by Galerie Sandy Toupenet; Memphis Group side table, 1990s, offered by Showplace • Luxury • Art • Design • Vintage; Robert Remer Drillium chaise lounge, new, offered by OPIARY; Flemish tapestry pillow, 17th century, offered by Y & B Bolour; Gerrit Thomas Rietveld tea cart, ca. 1945, offered by Mass Modern Design; Marcello Fantoni table lamp, 1950s, offered by CONVERSO; Mauro Mori Hug chair, new, offered by Les Ateliers Courbet; Bamboo sconces, 1960s, offered by John Salibello Bridgehampton; Guillerme et Chambron armchairs, 1960, offered by Galerie Klismos; Fornasetti Serratura tray, new; Bamboo chandelier, new, offered by Balsamo; photo of original room by Filippo Bamberghi

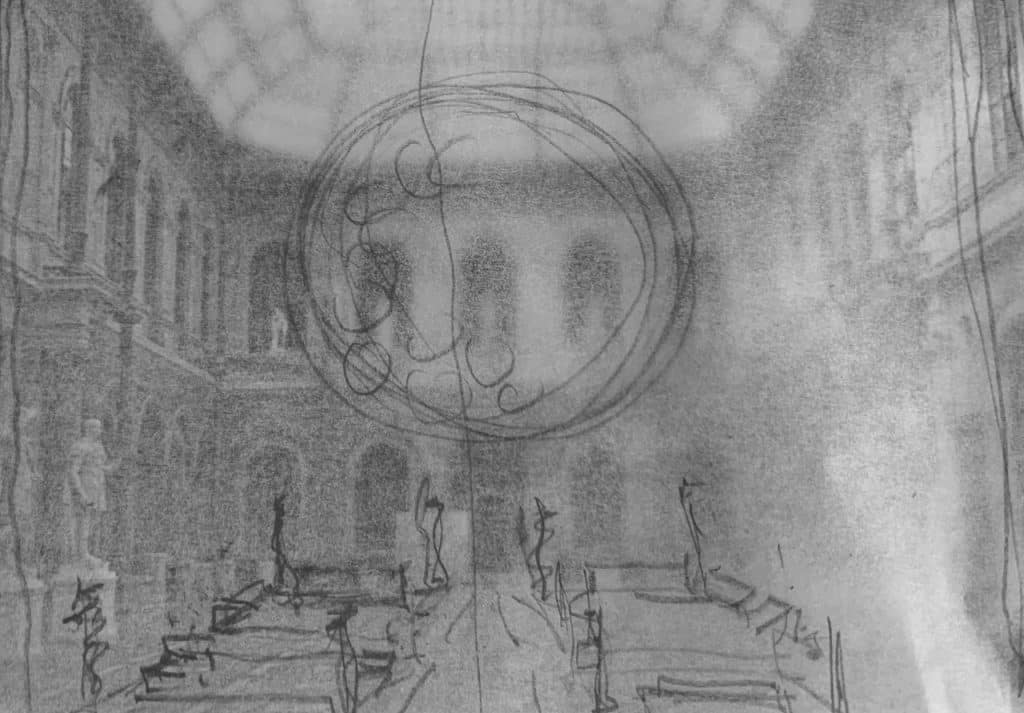

Palais des Études Courtyard, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris

Creator: Félix Duban • Built: 1830 (glassed over in 1863)

REIMAGINED BY: SHELTONMINDEL

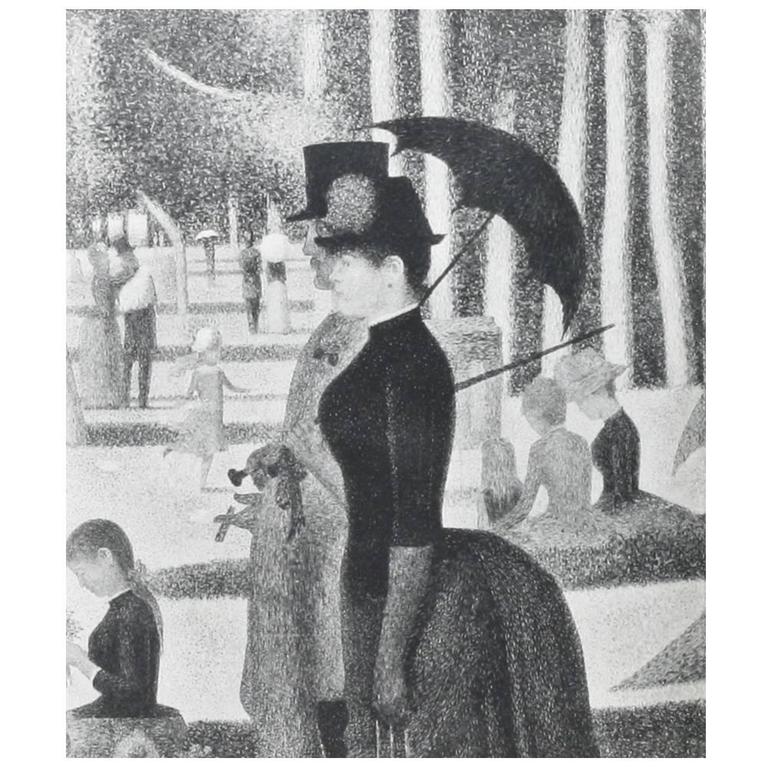

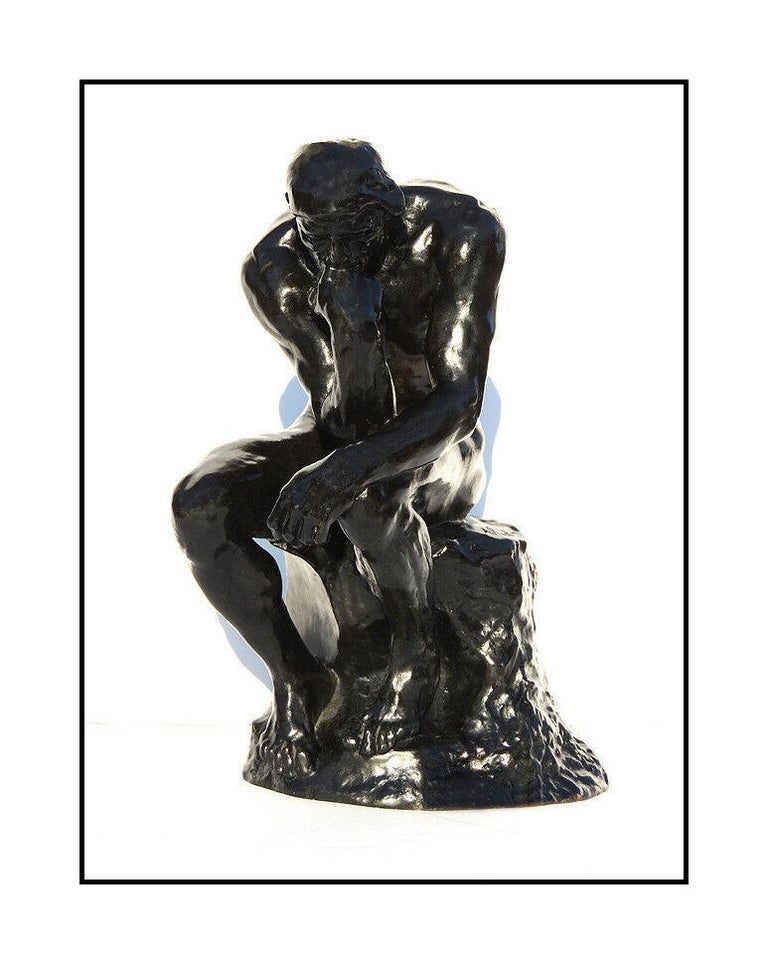

The team at New York–based SheltonMindel took a free-association approach to outfitting the storied art and design school’s famous exterior-interior space (used today as an exhibition venue for students’ work), in the process articulating a commentary on our times. The design is also, says firm founding principal Lee F. Mindel — rattling off names from the extraordinary roster of creatives who trained here over the past three centuries — “a celebration and commemoration of so many people from so many places who have contributed to our culture.”

“Given that Christo just died and had been slated to wrap the nearby Arc de Triomphe this spring,” he continues, they began by draping facing sections of the facade as an homage to the artist, who with his wife, Jeanne-Claude, famously wrapped another Paris landmark, the Pont Neuf, in 1985. “The purpose of this exercise was to make you think,” Mindel explains. Appropriately, Auguste Rodin’s Le Penseur (a miniature reproduction of which is available on 1stDibs) presides at the center, as it does in the garden of the Musée Rodin, the school’s Left Bank neighbor.

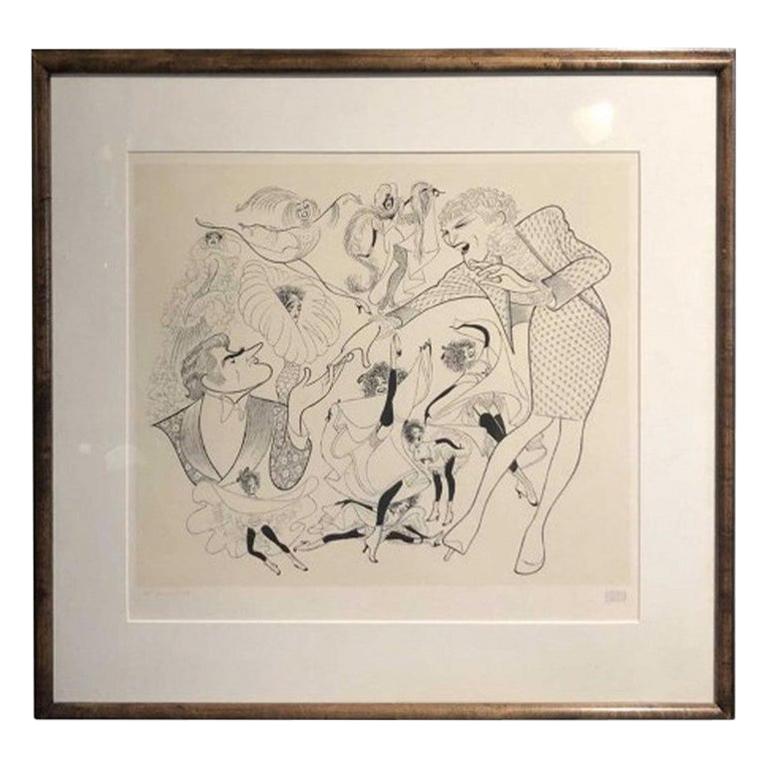

Crisscrossing the courtyard are characters pulled from paintings by Julian Opie. “They’re racially diverse and six feet apart,” he notes. “It’s social distancing at the École des Beaux-Arts.” A person with an umbrella brought to mind Georges Seurat’s most famous work, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of Grande Jatte, which, in turn, reminded Mindel, as much a historian of Broadway as of architecture, of Stephen Sondheim’s musical Sunday in the Park with George and its female lead, Bernadette Peters. “That got us thinking about theater,” says Mindel — and, eventually, about caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, who drew Peters. The witty artist used to secrete his daughter Nina’s name in his subjects’ hair and clothes, indicating how many Ninas were hidden in each work with a number next to his signature. In homage to this practice, appended to the “SheltonMindel” imprinted on the firm’s scheme is a 13, denoting the number of Opie figures it incorporates.

A final tribute goes to Isamu Noguchi. “The Beaux-Arts forms celebrate geometries like spheres and cubes and circles,” Mindel points out, “and there’s nobody as wonderful at doing that in paper as Noguchi.” The assemblage of paper lanterns overhead is by the Japanese-American artist, who serves as a poignant reminder that the U.S. has often failed to embrace its diversity. In 1942, during World War II, he voluntarily interned himself at a detention camp in Arizona to help fellow internees design and build parks and recreation areas. Not only did the government fail to realize any of these projects, but when Noguchi applied to leave, he was denied permission for six months.

“The beauty of Noguchi — and maybe it’s the beauty of diversity — lies in the fact that all the lines of his paperwork are made by hand and uneven,” says Mindel. “So, it looks like a resolved form from the exterior. When you move in closer, you see it’s made of many different bends and folds and the hand of man.”

Georges Seurat catalogue raisonné, 1961, offered by the Manhattan Rare Book Company; Statuettes, 2018, by Julian Opie, offered by RAW Editions; sculpture after Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker, 1998, offered by OriginalArtBroker; Isamu Noguchi Akari light, 1950s, offered byWYETH; La Cage aux Folles, 1970s, by Al Hirschfeld, offered by 4th Generation Antiques; photo of original room by Lee F. Mindel

Grand Salon, Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé Apartment, Paris

Creator: Jacques Grange • Built: 1890s • Designed: Late 20th Century

REIMAGINED BY: ROMANEK DESIGN STUDIO

“For somebody like me, who cannot stop accumulating objects,” Yves Saint Laurent once told Architectural Digest, “the absence of them is an oddity.” Emptying out the grand salon of the legendary French fashion designer’s Paris duplex — which he shared with his longtime partner, Pierre Bergé — is, however, exactly what Los Angeles–based designer Brigette Romanek did. “It wasn’t about filling it up,” she explains. “There was no way I was going to do that better than the original. This was about completely flipping the idea and making the room as strong as possible, with only a few key pieces to bring it to life.”

Gone are the treasures that once populated the stunning space at 55 rue de Babylone — the neoclassical bronzes and African art, the works by Jean Dunand, Eileen Gray, the Lalannes, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and countless others. (The auction of the apartment’s contents fetched almost $500 million at Christie’s in 2009.) Instead, the oak paneling now encircles an ode to Pierre Paulin, with his Alpha sofa and chairs occupying one end and his Tongue chaises — all of them upholstered in cream — scattered about the room, paired with Angelo Mangiarotti Nero Marquina marble coffee tables.

“It’s a very happy space you can enjoy, talk about, sit in, in different ways,” says Romanek. “You can sit upright and have a serious and intense conversation and then get in those Tongue chairs and laugh for hours. It’s a super elegant ‘hang’ space.”

The artwork, though comprising only three pieces, nevertheless nods to the omnivorous nature of Saint Laurent and Bergé’s collecting. “I would love to own a Roy Lichtenstein,” says Romanek, pointing to The Diver, which hangs above the sofa. “This was my chance to have one. His art for me is so graphic, so in-your-face and so present.” In period and style, that work could not be more different from Joanne Freeman’s blue-and-white abstraction or Eliza Kopec’s mixed-media Stella VIII.

If there is any thread connecting them to one another, as well as to the Paulin furniture in the room, it is their graphic nature. And this speaks to the uncluttered, relaxed simplicity Romanek was aiming to achieve. Everything, she says, has its “moment,” with enough room around it for you to really take it in.

Pierre Paulin Tongue lounge chair, ca. 1960, offered by Modern ID; Covers 24 Blue Summer AA, 2016, by Joanne Freeman, offered by IdeelArt; Christopher Kreiling Studio Nautilus floor lamp, new; Stella VIII, 2020, by Eliza Kopec, offered by Gallery40NL; Angelo Mangiarotti Triforglio coffee table, 1971, offered by soyun k.; Pierre Paulin ABCD settee, 1970s, offered by 20CDesign.com; stainless-steel garden planters, 1960s, offered by 20CDesign.com; The Diver, 1948, by Roy Lichtenstein, offered by Ro Gallery; photo of original room by Pascal Hinous/Conde Nast/Getty Images

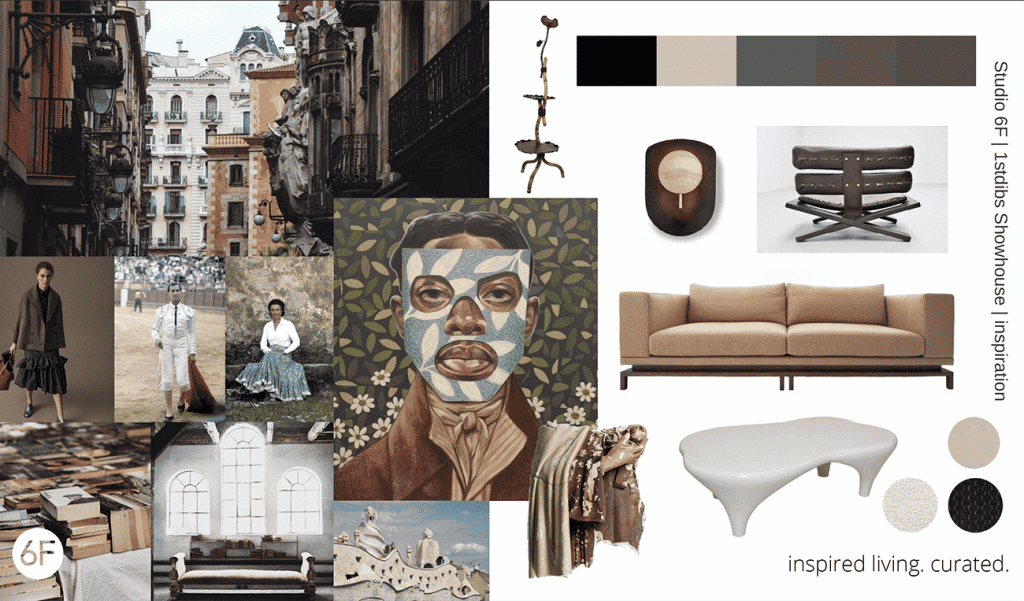

The Loft, Casa Batlló, Barcelona

Creator: Antoni Gaudí • Built: 1877 • Redesigned: 1904–06

REIMAGINED BY: GIL MELOTT, OF STUDIO 6F

“I’m an Antoni Gaudí fan for a very specific reason,” says Gil Melott, founder of Chicago-based design firm Studio 6F. “He often spoke about being attracted to things in nature. To paraphrase him: If you take your cues from nature, you’re often designing for your Creator. I tend to work on things with that approach,” Melott continues, “in the abstract with nature. I’m inspired by the trees and the canyons around which I grew up in Central Texas.”

Because of its catenary arches, the loft space atop Gaudí’s Casa Batlló has been likened to the ribcage of a whale or — for those who maintain that the building is an architectural allegory of the St. George legend — a dragon. Rib-like elements are a recurring motif in many of the pieces of furniture and art Melott selected for his redecoration of the space: the base of an Art Deco bar cabinet, Sonja Wasseur chairs, a fishbone sculpture by Steven Haulenbeek and a skeletal Japanese floor lamp. Alone, they stand as exceptional works. But within the context of Gaudí’s allusive architecture, they acquire new meaning.

Melott’s room appointments also pick up on other references suggested to him by the blank, all-white environment. “I look at a space as having history, whether it has history or not,” he says. “If you look at this space empty, to me it has a sense of serenity and religion.” Objects he chose to invoke this sense include a sculpture titled I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, 2014, by Jennifer Small, known for recontextualizing devotional articles as sculpture; an antique mahogany library table one might find in a refectory; and a Tommi Parzinger floor lamp that recalls a hand-forged church candelabrum. (Genuflection is not required.)

Then, there is the “history” of the fictional family who lives here. Melott imagined them as requiring a room serving multiple generations and purposes. Here, adults can gather on the Flotar sofas of Melott’s own design, with drinks from the Italian 1930s bar, while kids play games and do homework at a Paul Evans coffee table, while perched on faux-bamboo-framed wing chairs and Wasseur seating.

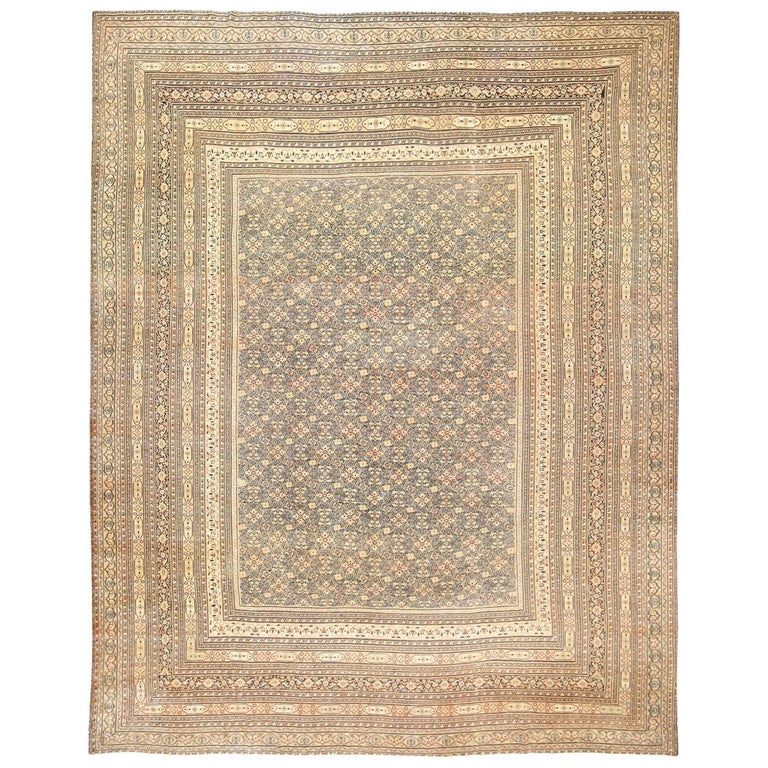

Gil Melott Flotar sofa, new, offered by Studio 6F; I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, 2014, by Jennifer Small, offered by Art Mûr; Jacques Jarrige Toro table, new, offered by Valerie Goodman Gallery; Persian Khorassan carpet, ca. 1920, offered by Nazmiyal; Sonja Wasseur Buddha chairs, 1974, offered by Mass Modern Design; Art Deco dry bar, 1930s, offered by Fins de Siècles; Tommi Parzinger floor lamp, 1950s, offered by Lobel Modern; Azadeh Shladovsky Studio Charme magazine table, new; Gil Melott Luz SC Form 19 sconce, new, offered by Studio 6F; Blue Mud Herd, 2020, by Amy Laugesen, offered by Ann Korologos Gallery; library table, 1900, offered by WYETH; Han Dynasty terracotta jug, 206 B.C.–A.D. 200, offered by FEA Home; mid-century-modern-style lounge chairs, new, offered by This Place; Paul Evans Stalagmite coffee table model PE-128, 1970, offered by Milord Antiques; Art Deco floor lamp, 1930s, offered by Ambianic; “Fishbone” series sculpture, 2018, by Steven Haulenbeek, offered by Studio 6F; He Was a Crusader of the Voiceless and He Played the Clarinet, 2020, by Ronald Jackson, offered by De Buck Gallery; photo of original room by Art Kowalsky/Alamy

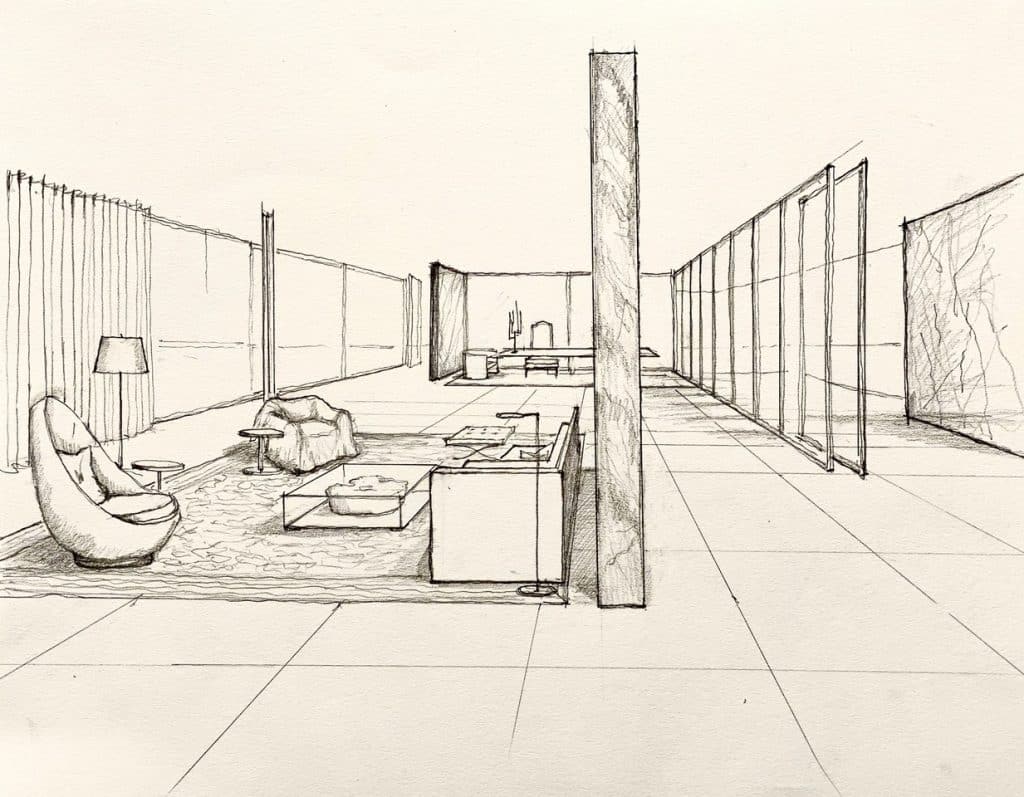

Barcelona Pavilion, Barcelona

Creator: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich • Built: 1928

REIMAGINED BY: SOLÍS BETANCOURT & SHERRILL

Over the years, José Solís Betancourt made many visits to the German Pavilion that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich designed for the 1929 Barcelona International Exhibition. And all that time, says Betancourt, co-principal of Washington, D.C.–based firm Solís Betancourt & Sherrill, “I’d been sketching, thinking how to change it into a residence. How could I live here?”

So, there was no question about what room he and his business partner, Paul Morgan Sherrill, would choose for this showhouse. “I’ve always liked the contrast between modern architecture and traditional furnishings, and the other way around,” says Solís Betancourt, describing his studio’s signature style. The particular blend deployed in their design for the pavilion, he explains, was “about making it soft. You still would be minimal, still clean-lined, still respect the space. But it would feel very comfortable.”

The pair established this sensibility by pushing the envelope on tactility. First, they laid an antique Persian Sultanabad carpet that picked up the colors of the onyx and alpine-green-marble walls defining the living room area. Around this, they assembled a contemporary Christophe Delcourt sofa upholstered in a nubby alpaca-like fabric; a chair draped with what Solís Betancourt calls a “fur coat,” which softens and animates its steel form; and a Milo Baughman swivel chair with a soothing oval shape that provides a pleasing contrast with the rigorously rectilinear architectural envelope. This last item, as well as a throne-like Gianfranco Ferré chair in the adjacent dining-office space, also introduces a striking verticality. “The pavilion tends to be very horizontal. You feel that powerful axis of the horizon,” observes Solís Betancourt.

Individual pieces serve specific functions, too. The Baughman swivel allows the sitter to pivot toward the placid view of the reflecting pool and the Georg Kolbe sculpture outside. A looser, organic element is added by the glass-enclosed tree stump of the coffee table, which, says Solís Betancourt, “is some weird contradiction of bringing in nature, but a little bit controlled.” The sofa has side panels that fold in to create a more confined space within the open plan. These items introduce versatility in a minimalist way that respects the architects’ vision. “When you have such an amazing building, it’s not about decorating,” he concludes. “It’s more about design. If the architecture is perfect, you don’t need very much.”

Atelier Von Pelt Lupo chair, new, offered by Rossana Orlandi; Colen Colthurst CC tables, new, offered by Porch Modern; Persian Ziegler Sultanabad rug, 1920, offered by Mehraban Rugs; Laurel Lamp Company floor lamp, 1960s, offered by DEN; Ludvig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich Barcelona chair and ottoman, 1929, 1980s reissue, offered by Ventura; Christophe Delcourt Eko sofa, 2018, offered by vingtième; Foster + Partners for Lumina Flo floor lamp, new; Milo Baughman Egg chair, 1960s, offered by Retro Inferno; Pace Collection side tables, 1980s, offered by Modern Drama; Studio Roeper Treasures of Decay coffee table, new; photo of original room courtesy of Solís Betancourt & Sherrill

Forum Baths, Pompeii

Creator: Unknown • Built: ca. 79 B.C.

REIMAGINED BY: NICOLE FULLER INTERIORS

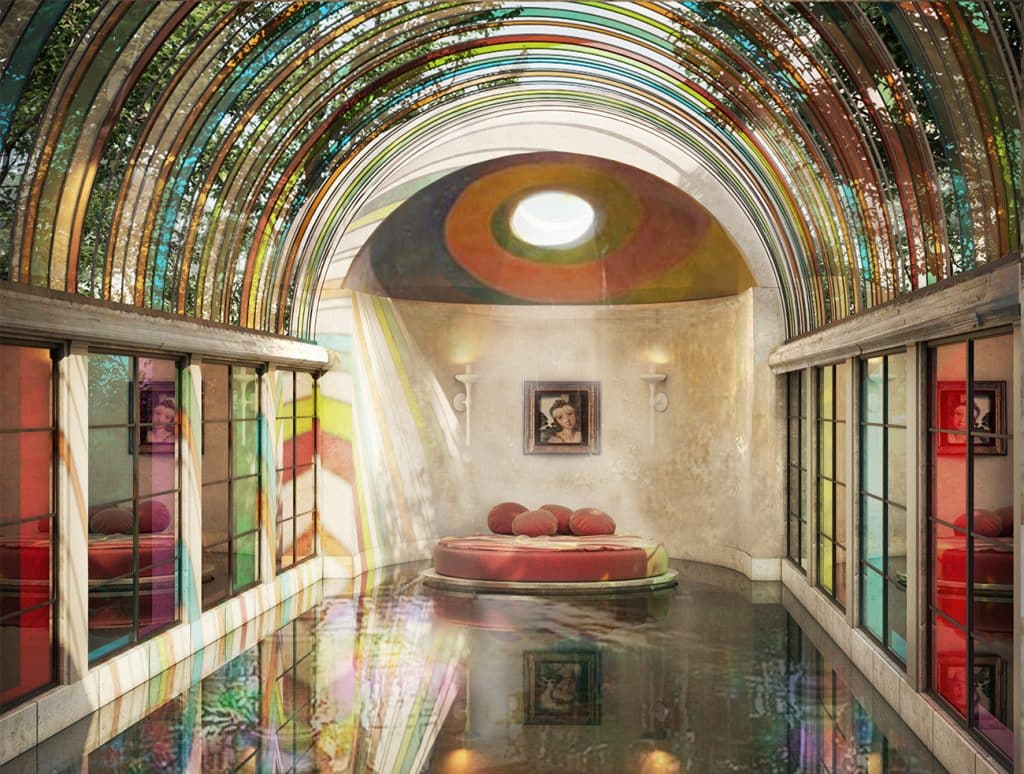

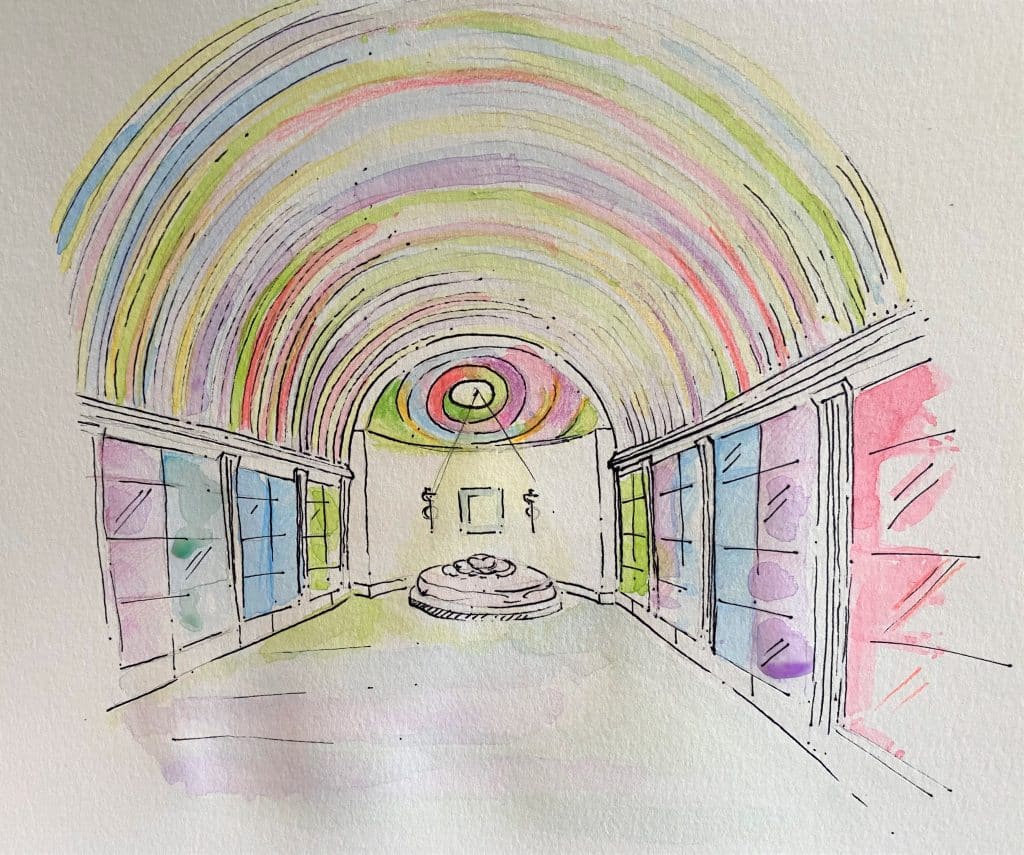

Until the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, in 79 A.D., the citizens of Pompeii enjoyed daily excursions to the public baths, located behind the Temple of Jupiter. A favorite spot for the men was the caldarium, or hot bath, a vaulted hall filled with steam and containing a basin of cold water at one end in a domed niche. When designer Nicole Fuller, who has offices in Los Angeles and New York, saw a picture of this ancient space, she recalls, “I immediately had this concept of light, chromotherapy and reflection. It spoke to me about introspection, self-care.”

Like many of us, she craved a respite from the tumult of our times. Her response, possible only in a virtual world, flagrantly flouts all standards of architectural preservation. Fuller blew out the ceiling and walls, replacing them with multicolored stained glass, and flooded the room with water to create a pool. A round bed now floats where the cold basin once stood, a polychromatic fresco swirling overhead. In the real world, this would have been desecration, but here it becomes a mesmerizing flight of fancy.

“It has light, which has an incredible stimulating effect on the human psyche,” Fuller says of the new solarium. “It has color therapy, which can really alter someone’s mood. It can give you confidence and boost your spirits. And it has water. Water, water therapy and the movement of water are very stimulating and can have a lot of healing properties. With everything that’s happened in the world, it has been a time to just heal, to care for yourself and care for others around you, and to be really quiet.”

The contemplative aquatic environment, she continues, was meant “for you to swim to the bed through the color, through the reflections of light, come up and be there with God’s rays of light. To meditate and reflect on who you are — as a creative, as a businessman or woman, or as an activist.” The domed niche is simply appointed with an Italian 16th-century Botticelli-like portrait flanked by plaster Giacometti-style sconces and the fresco. The bed had to be round, Fuller felt, to represent “infinity and endless possibilities. An opportunity to love more, laugh more, create more.” Certainly, all things seem possible in the stillness induced here.

Portrait in the manner of Botticelli, 16th century, offered by Ottocento; Giacometti-style sconces, new, offered by Lerebours Antiques; Juan Montoya bed, 1991, offered by BG Galleries; photo of original room by DeAgostini/Getty Images

Bedroom, Villa Mabrouka, Tangier

Creator: Jacques Grange • Designed: Late 20th Century

REIMAGINED BY: PETER MIKIC INTERIORS

“As you develop, grow and get older, you start thinking about how you want to live,” says Australian-born, London-based designer Peter Mikic. “Halfway through our lives, we want to be bigger and better, and then the next half we want to get smaller and simpler.” This certainly was true for Yves Saint Laurent. Speaking of the couturier’s final Moroccan residence, Villa Mabrouka, in Tangier, his interior designer, Jacques Grange, once said, “For the first time in his life, Yves wanted a restful, open, happy environment — not a treasure palace.”

“By that stage, he was well and truly over the social scene of Paris,” says Mikic. “It’s all pretty simple. I think there’s a place for that, especially when you’re down by the sea.” For his reinterpretation, Mikic took much of his inspiration from the views of the Strait of Gibraltar and coastal Spain visible from the site, a cliff hovering above the city. These informed the palette, a “mix of those turquoise and emerald greens that were already in the room,” as well as the contemporary Murano glass chandelier that replaces the original ornate one while sharing with it a similar aqua hue. Mikic also laid a green-dyed Turkish rug and stood a marine-blue and white totem by Ettore Sottsass (a favorite designer of his) in a corner. A shell-encrusted mirror over the fireplace continues the seaside theme.

There are references to other Saint Laurent homes, as well. Pointing to an Egyptian-ish Giacometti cat sculpture, Mikic explains, “Most of his houses were Tutankhamun-like.” But the design alludes in particular to the iconic villa at the Majorelle Garden, in Marrakech, now a museum. A bed by Osvaldo and Valeria Borsani, for instance, sports a motif of inverted keyholes, summoning the Moroccan spirit in a stylishly modern way. Less expected is a sun-yellow Blown Up chair by Schimmel & Schweikle for Alfa.Brussels. That the chair is 3D-printed would likely have thrilled Saint Laurent, who was known for channeling the latest new thing into his fashions (pioneering clothes, for example, that picked up on both youth and street culture). “I tried to imagine what he might have wanted if he were alive and doing the villa today,” says Mikic.

Osvaldo and Valeria Borsani bed, 1971, offered by CONVERSO; Schimmel & Schweikle Blown-Up armchair, new, offered by Goldwood Interiors; Tramp Art frame, ca. 1900, offered by the Antique Warehouse; Scarlet Splendour Cheer bedside tables, new; Marie Suri Aster fire screen, new, offered by Liz O’Brien; TOTEM Clair de Lune, 1992, by Ettore Sottsass, offered by GALERIE HARTER; Tess Morley mirror, new, offered by Tarquin Bilgen Antiques; Untitled woodcut, 1990, by Günther Förg, offered by MLTPL; Vistosi table lamp, ca. 1960, offered by Pegaso Gallery Design; Le Chat maître d’hôtel, 20th century, by Diego Giacometti, offered by GALERIE BLACK; Baker Furniture Company console, ca. 1975, offered by Tom Robinson Modern; Jean Roger lamps, 1970s, offered by Fleur; Murano glass chandelier, 2015, offered by Galleria Veneziani; overdyed Turkish rug, 1950, offered by J&D Oriental Rugs Co.; photo of original room by Guido Taroni

Nelson Rockefeller Living Room, New York

Creators: Jean-Michel Frank, Henri Matisse and Ferdinand Léger • Built: 1926 • Designed: 1934

REIMAGINED BY: SUZY HOODLESS

Some things you just don’t mess with. In 1934, when Nelson Rockefeller moved into 810 Fifth Avenue, he assembled a dream team to design the 47-foot-long living room: Matisse and Ferdinand Léger to paint murals around the salon’s two fireplaces and Jean-Michel Frank to furnish it. Rockefeller also hung the room with Picassos. “I didn’t think I could really just throw out the Picassos and Matisse and Léger,” says London-based designer Suzy Hoodless with a wry smile.

So, Hoodless retained these great works in her redesign, as well as the colorful carpet Frank commissioned from Christian “Bébe” Bérard. But there the reverence stopped. As elegant as all the furnishings were, Frank had lined them up around the perimeter of the room. “The original layout almost feels like a waiting room, potentially quite old-fashioned,” observes Hoodless. “Rooms need to have a rhythm and a pace. They’re there to provoke conversation, to be fun and lived-in and have humor.” Drawing on her love of Scandinavian design, she populated the center of the space with a pair of 1951 Runar Engblom chairs facing the Matisse-decorated fireplace over a Paul Evans coffee table. Throughout, she created seating areas using mid-century modern pieces: a Hans Olsen bench, a Kaare Klint leather armchair and two T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings Mesa sofas.

Why primarily Scandinavian? “The proportion and scale of the pieces are sort of effortless,” says Hoodless. “They’re very low-key, ergonomic, very well-designed, but they’re not showy, not flashy. That’s a similar sensibility to Jean-Michel Frank’s.”

So much color in a room was atypical for Frank, but something Hoodless ran with. “I find color a very powerful tool,” she explains. “Stylistically it says a lot about a space. You can use it to great effect.” For evidence, witness the Italian 1970s polychromatic “tainted mirror” cabinets flanking the Matisse mural. (The lighting Hoodless selected is also Italian.) But it is the room’s unforced ease that most attracts. “I just wanted to have fun with it,” concludes Hoodless. “It’s approachable and comfortable and usable, and a celebration of everything the space already is.”

T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings Mesa sofas, 1952, offered by CONVERSO; Studio Glustin cabinets, 1970s, offered by Galerie Glustin; Murano glass chandelier, 1980s, offered by Metropolis Modern; Hans Olsen modular TV bench model 161, 1957, offered by circa20c; Tommaso Barbi Leaves floor lamp, ca. 1970, offered by AIMO ROOM; Kaare Klint goatskin armchair, 1930s, offered by Vance Trimble; enameled-iron martini tables, 1950–75, offered by Dorian Caffot de Fawes Ltd.; Poul Henningsen Water Pump floor lamp, 1930s, offered by Studio Schalling; Marzio Cecchi Porcospino table lamp, 1973, offered by Watteeu; Paul Frank wall lights, ca. 1950, offered by VN Vintage & Modern; Hans Bergström three-arm floor lamp, 1940s, offered by Studio Schalling; Carl Malmsten Redet easy chairs, 1930s, offered by MORENTZ; Runar Engblom armchairs, 1951, offered by Kabinet Hubert; Paul Evans coffee table, 1960s, offered by Lost City Arts; photo of original room by Ezra Stoller/Esto

Lansdowne Dining Room, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Creator: Robert Adam • Built: 1761–69

REIMAGINED BY: JAYNE DESIGN STUDIO

Robert Adam designed the dining room at Lansdowne, in London’s Berkeley Square, as an “apartment of conversation,” but with a specific difference. While other such rooms were usually hung with damasks and tapestries, this one, he wrote, was “finished with stucco, and adorned with statues and paintings that they may not retain the smell of the victuals.”

As New York designer Thomas Jayne, notes, “In the twenty-first century, the era of cigars and big joints of meat and cooking smells are not as much decorating issues as they were even a generation ago.” This gave Jayne and his associate William Cullum freedom to deploy 1950s Jules Leleu fruitwood chairs upholstered in tapestry and curtains based on a 19th-century palampore hanging from India.

The designers also gave themselves the more substantial liberty, as Jayne explains, “to take something that’s decidedly eighteenth century and respect that, then bring it into the twenty-first century in a new way. We kept the original purpose available but made it suggest a contemporary use.” That meant reconceiving the space — which can be visited today as one of the period rooms in the recently redone British galleries for decorative arts and design at the Metropolitan Museum of Art — as a multifunctional great room with both lounging and dining capabilities. At one end is a seating area composed of a 1950s Maison Leleu sofa, circa 1900 bamboo chairs and a flowery porcelain Minton garden seat arranged around a Regency-style ottoman. At the other, those Leleu fruitwood chairs gather about a 1967 red-lacquer and resin pedestal table by Otto Zapf.

“One of our strengths is mixing decorative arts and periods of different cultures,” says Cullum. “Not only do we have things spanning the eighteenth to twenty-first centuries, we also span cultures — for instance, in the Chinese lanterns and the palampore-inspired curtains.” The artistry, adds Jayne, derives from “having them all have gentle relationships, so it’s not jarring. Great design is about contrasts. The fact that we have a Giacometti sculpture next to an eighteenth-century Delft bottle and two cloisonné elephants in front of a classical sculpture is a bit of a tour de force.”

Lest things got too serious, the pair heightened the color too. “It was a way to bring the room down,” says Cullum. Adds Jayne, “It also makes you see the room at the Met in a new way.”

Bamboo seating set, ca. 1900, offered by the Renner Project; Kashmir red paisley pillows, 19th century, offered by Antique Textiles Galleries; Chinese lantern, 19th century, offered by Pagoda Red; Jules Leleu dining chairs, 1956, offered by Gary Rubinstein Antiques; faux porphyry pedestal, 2019, offered by Gerald Bland Inc.; crackleware porcelain vase, ca. 1860, offered by Timothy Langston Fine Art & Antiques; Indian palampore Tree of Life wall hanging, 19th century, offered by Andrea Aranow Textiles; Minton ceramic garden seat, 19th century, offered by Galerie Vauclair; Edward F. Caldwell and Co. floor lamp, early 20th century, offered by David Skinner Antiques; Maison Leleu sofa, 1950s, offered by Blend Interiors; Shibori throw pillows, 1980s, offered by Antique Textiles Galleries; stool after Thomas Hope, 2012, offered by Tarquin Bilgen Antiques; celadon porcelain bottle vase, 19th century, offered by Timothy Langston Fine Art & Antiques; patchwork paisley bolster, 19th century, offered by Antique Textiles Galleries; Victorian walnut bookcase, ca. 1870, offered by Nimbus Antiques; Le Chat maître d’hôtel, 20th century, by Diego Giacometti, offered by GALERIE BLACK; blue-and-white bottle attributed to Nevers, ca. 1750, offered by Bardith; Chinese cloisonné elephant candlestick, 20th century, offered by Nick Brock Antiques; Otto Zapf table, ca. 1967, offered by inside-room; creamware dishes, ca. 1800, offered by Bardith; blackened-brass candleholders, 2017, offered by Konekt; photo of original room by Joseph Coscia/courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Grand Staircase, Presidential Suite, the Greenbrier, White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia

Creator: Dorothy Draper • Built: 1913 • Designed: 1948

REIMAGINED BY: COURTNEY MCLEOD, OF RIGHT MEETS LEFT INTERIOR DESIGN

“Sometimes she goes a little far,” says New York interior designer Courtney McLeod, referring to the maximalist decorator Dorothy Draper, doyenne of modern Baroque style. “She liked a big gesture, and sometimes multiple big gestures in the same space. If I had to boil it down to one word, it would be fearless.”

Exhibit A: This sweeping staircase at the Greenbrier — the West Virginia hotel that was arguably her most famous commission — with its scarlet carpet runner, über-stuffed and tufted double chaise and exuberant, floor-to-ceiling orchid-patterned wallpaper. McLeod’s “a bit over-the-top” addition, she says, is a customized Geo wallpaper from the boutique hand-painted-paper company Porter Teleo. The same idea, McLeod says, underlies what Draper was doing and what she has added: “to overwhelm you in the space with something very beautiful. The palette paired with the mural really sets up that Art Deco vibe I’m going for.”

The mix of olive, pale blue, black and cream is certainly very high-contrast Draper in mood. But it exposes a bit of McLeod’s own fearlessness, although not in the way one might expect. “My color sense tends to be bolder,” she explains. “I don’t often play with more tonal palettes. That’s what I was really attracted to with this, to challenge myself to do something different.”

The Geo pattern obliquely evokes the era, as well as what came to be known as the signature “Draper touch.” So do a contemporary Alexandre Logé Magritte pendant lamp (made of plaster, a favorite Draper material) and a round Ghirò Studio table (“It has an almost Machine Age feel to it, but a very refined and elegant one,” says McLeod).

Other furnishings are more literally Deco, such as a round 1920s rug and 1940s armchairs by Jules Leleu and a Jacques Adnet leather room screen. Some are less expected. A Vladimir Kagan sofa “feels wrong but in a good way,” McLeod says. “All the curves and sensuous lines — there’s something feminine about it, even though it’s a masculine palette.”

As with all the virtual showhouse rooms, it’s tempting to contemplate what the original creator of the room would have thought of its reinterpretation. “She would be mortified,” says the designer with a laugh. “But that’s okay and absolutely no disrespect to one of my idols.”

Jacques Adnet screen,1950s, Vintage Domus SRL; Naomi Clark fabric, new, offered by Fort Makers; Jules Leleu armchairs, ca. 1940, offered by Conjeaud and Chappey LLC; Alexandre Logé Magritte pendant light, new, offered by Donzella Ltd.; Christophe Côme cabinet, new, offered by Cristina Grajales Gallery; Vladimir Kagan model 176SC sofa, 1952, 1980 reissue, offered by Obsolete; Ghiró Studio round table, 2016, offered by Donzella Ltd.; Georges Jouve ashtray, ca. 1950, offered by DADA; Jules Leleu round rug, 1920s, offered by Nazmiyal; Studiopepe Hello Sonia stair rug, new, offered by CC-Tapis; Ghiró Studio mirror, new, offered by Donzella Ltd.; photo of original room courtesy of the Greenbrier