By Nancy Genn

Located in San Francisco, CA

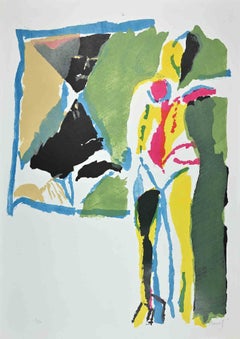

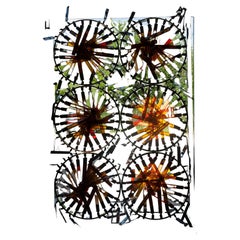

This artwork titled "Spring 69" 1969 is an original color lithograph by American artist Nancy Genn, b. 1929. It is hand signed, titled and inscribed Artist Proof in pencil by the artist. The size is 23.75 x 34.65 inches. It is in excellent condition, it has very small marks in the back due to tape removal from previous framing, not visible from the front.

About the artist:

Nancy Genn is an American artist living and working in Berkeley, California known for works in a variety of media, including paintings, bronze sculpture, printmaking, and handmade paper rooted in the Japanese washi paper making tradition Her work explores geometric abstraction, non-objective form, and calligraphic mark making, and features light, landscape, water, and architecture motifs. She is influenced by her extensive travels, and Asian craft, aesthetics and spiritual traditions.

Genn's first noted solo exhibition was in 1955 at Gump's Gallery in San Francisco. She received international recognition through her inclusion in French art critic Michel Tapié’s seminal text Morphologie Autre (1960), which cited her as one of the most important exponents of post-war informal art. Her abstract expressionist paintings of this period, continuing through the mid-1970s, featured all-over compositions of colorful layers of gestural brushwork and calligraphic mark making resembling asemic writing.

In 1961, Genn began creating bronze sculptures using the lost-wax casting method. Influenced by noted sculptor and family friend Claire Falkenstein, who used open-formed structures in her work, Genn cast forms woven from long grape vine cuttings, and produced vessels, fountains, fire screens, a menorah, a lectern, and, notably, the Cowell Fountain (1966) at UC Santa Cruz. In 1963 her sculptural work was exhibited with Berkeley artists Peter Voulkos and Harold Paris in the influential exhibition Creative Casting curated by Paul J. Smith at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, New York.

Genn was one of the first American artists to express herself through handmade paper, first receiving wide recognition via exhibitions at Susan Caldwell Gallery, New York, beginning in 1977, and in traveling exhibitions with Robert Rauschenberg and Sam Francis. In 1978-1979, supported by the National Endowment for the Arts and Japan Creative Arts Fellowship, she studied papermaking in Japan, visiting local paper craftspeople, working in Shikenjo studio in Saitama Prefecture,[5] and exhibiting her work in Tokyo. She also learned techniques from Donald Farnsworth...

Category

Early 20th Century Abstract Expressionist Marcello Avenali Art