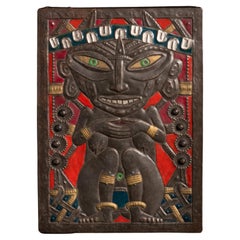

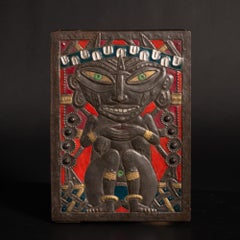

By Alfred Daguet

Located in Palm Beach, FL

Like armored shields, Alfred Daguet's bold pair of bronze roundels are veritable aesthetic rallying cries for the forward march of Art Modernity. In subject, material, and form Daguet audaciously presents the tough side of Art Nouveau. His masterful metalwork in repoussé creates spiky fins and rays in hard relief whose rigid, horizontal lines dramatically contrast wth their protruding, undulating spines to lend his venomous Lionfish a quality of powerfulness and propulsion.

Having worked closely with Sigfried Bing in his Paris workshop set up above Bing's famed Maison l'Art Nouveau until 1905, Daguet had ready access to raw materials such as glass cabochons, wall papers, and silk fabrics from adjoining studios which he often included in his metal craft. In this milieu of artistic exchange, Daguet also made use of the available books and other source material for both visual and philosophical inspiration, such as Anton Seder's wildly popular Das Thier, from which there can be no doubt that these roundels were divined.

Seder, the director of the Ecole Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs (College of Decorative Arts) in Strasbourg and co-editor of the journal, Das Kunstgewerbe in Elsass-Lothringen (The Arts and Crafts in Alsace-Lorraine), made a huge impact on the art world with his publication of Das Thier in Der Decorative Kunst Serie 1-2 (Animals in Decorative Art) released between 1896 and 1909. It contained striking chromolithographic images of animals and mythical dragons presented as decorative motifs. As an educator and disseminator of a modernist aesthetic doctrine, it was Seder's illustrations more so than his pedagogy which reached the widest audience to truly further his Modernist beliefs. Much like Bing, who espoused the Modernist conviction that elevated the Applied Arts to the same level plane as the Fine Arts and thereby integrating his retail and studio enterprise under the same roof, Seder included art workshops in his school and also championed the belief that the Applied Arts are equal to the Fine Arts. Both Seder and Bing wrote about the revolutionary role Applied Arts should play in paving the way for a Modern Art where an analysis of the past goes hand in hand with the observation of Nature and where lessons from craft in particular have a special ability to reach the greatest number and stir interest and love of art.

Daguet's two Lionfish unmistakably draw from Seder's Das Thier Art Nouveau illustrations. Despite the hard and spiky quality of his metalwork, Daguet leans heavily on the stylistic qualities of Art Nouveau. Propulsive movement is suggested by the graceful back motion of the whisker fins and by the way the attenuated ends of the spiky fins twist and undulate around the fish like marine plant life. Daguet plays with texture, enhanced by chasing and stippling, to achieve a quality of contrast in light and dark on the fish's bodies. These qualities reference naturally occurring camouflage such as counter-shading found on fish where the dorsal surface is dark and the belly light in order to evade detection. While directly referencing nature, Daguet uses these superimposed forms found on the fish to create an abstract and stylized pattern. Another effective naturalistic detail Daguet works into his design motif is disruptive coloration in which the stripes on a fish blend into the background of the sea environment to break up the fish's outline against plant stems, reeds and other sea vegetation. In this case, however, Daguet superimposes his fish against a golden orange background, like an aureole, which is framed by a convex border resembling a Medieval battle...

Category

Early 1900s Art Nouveau Alfred Daguet Furniture