Items Similar to Writings 117, Cheung Yee, handmade cast paper painting dark brown, turtle shells

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 6

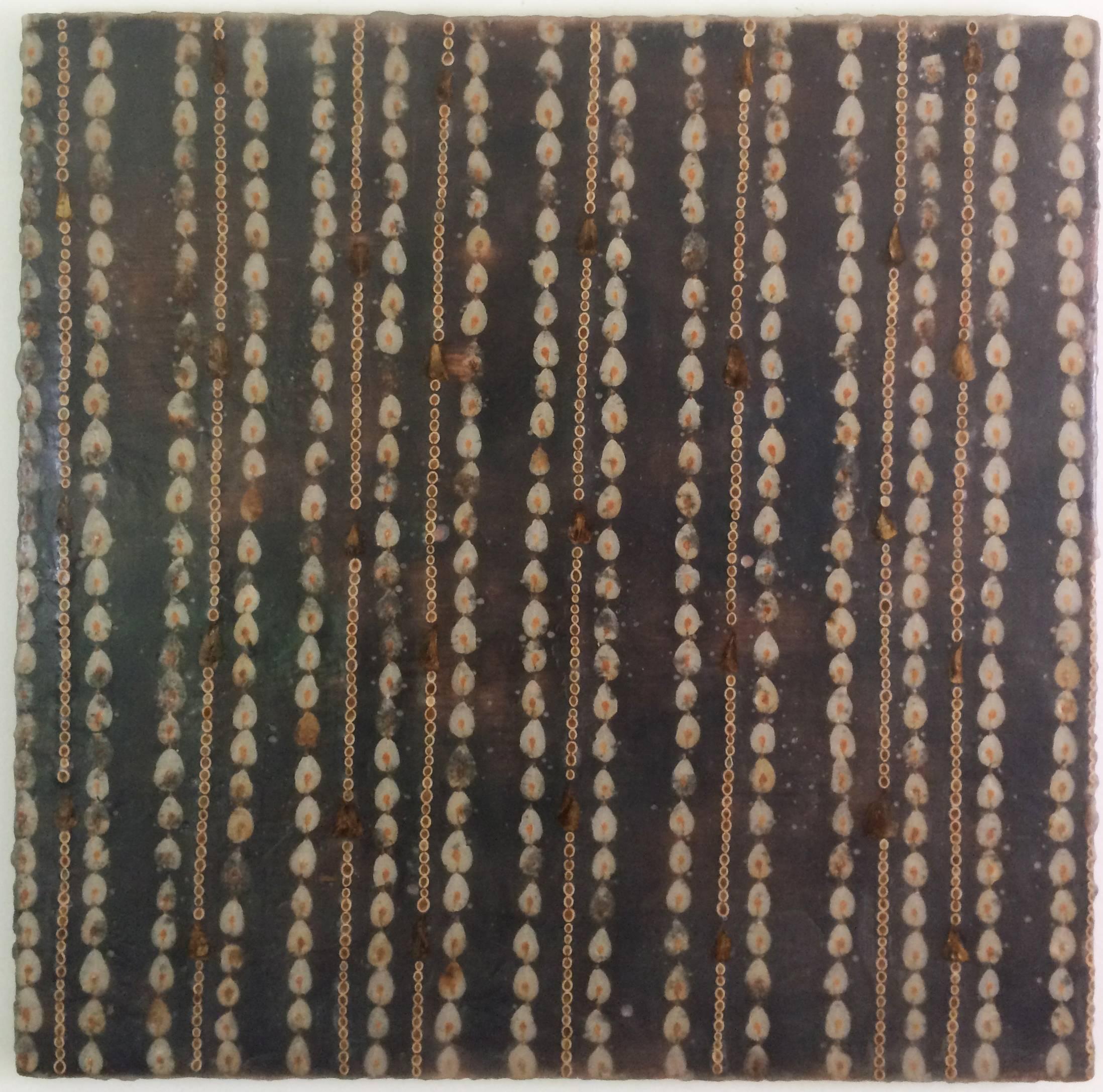

Cheung Yee (Zhang Yi)Writings 117, Cheung Yee, handmade cast paper painting dark brown, turtle shells

Price Upon Request

Price Upon Request

Price Upon Request

Price Upon Request

Price Upon Request

Price Upon Request

Price Upon Request

Price Upon Request

Price Upon Request

Price Upon Request

About the Item

Writings 117, Cheung Yee, handmade cast paper painting dark brown, turtle shells

handmade cast paper painting.

Oracle bones (Chinese: 甲骨; pinyin: jiǎgǔ) are pieces of ox scapula or turtle plastron, which were used for pyromancy – a form of divination – in ancient China, mainly during the late Shang dynasty. Scapulimancy is the correct term if ox scapulae were used for the divination; plastromancy if turtle plastrons were used.

Diviners would submit questions to deities regarding future weather, crop planting, the fortunes of members of the royal family, military endeavors, and other similar topics. These questions were carved onto the bone or shell in oracle bone script using a sharp tool. Intense heat was then applied with a metal rod until the bone or shell cracked due to thermal expansion. The diviner would then interpret the pattern of cracks and write the prognostication upon the piece as well. By the Zhou dynasty, cinnabar ink and brush had become the preferred writing method, resulting in fewer carved inscriptions and often blank oracle bones being unearthed.

The oracle bones bear the earliest known significant corpus of ancient Chinese writing and contain important historical information such as the complete royal genealogy of the Shang dynasty. When they were discovered and deciphered in the early twentieth century, these records confirmed the existence of the Shang, which some scholars had until then doubted.

Art Asia Hong Kong - HK Convention & Exhibition Center

Art Trends 95 - HK Convention & Exhibition Center

Group show at Crown Art Center, Taipei, Taiwan

Group show at Hampshire Art Gallery, Taichung, Taiwan

Faculty show of Fine Arts Department, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

1996

Taipei & Hong Kong Leading Artist Exhibition, Museum Annex, Hong Kong

The 11th Asian International Art Exhibition, Metropolitan Museum of Manila, Philippines

Exhibition at Artpreciation Gallery, Hong Kong

1997

Faculty show of 40th Anniversary of Fine Arts Department, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Participated in joint exhibition of One Country, Two Perspectives at Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong

2000

Exhibition - The Art of Cheung Yee in Singapore

2001

Solo exhibition - Past and Present at Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong

2002

Exhibition at Artpreciation, Singapore

2003

Exhibition at Artpreciation, Singapore

2004

Solo exhibition, Perceptive Impressions, at Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong

Participated in The 30th Anniversary Exhibition at Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong

2007

Joint exhibition at Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong

HONORARY SERVICE

Chairman of Hong Kong Sculptor Association

Adviser of Visual Art Society of Hong Kong

Adviser of Hong Kong Institute of Visual Studies

Adviser of Hong Kong Graphics Society

Adviser of Hong Kong Museum of Art

Adviser of Regional Council Museum of Hong Kong

COLLECTION

Hong Kong Museum of Art

Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City

National Museum of History, Taipei, Taiwan

Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taiwan

Taiwan Museum of Art, Tai Chung, Taiwan

Kaohsiung Fine Arts Museum

Private collections in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Philippines, Sweden, Switzerland, England, U.S.A., Canada, Japan, Germany, Australia, Thailand, Mexico, Brazil, Italy, Greece, India, Sri Lanka, Spain, France and New Zealand

- Creator:Cheung Yee (Zhang Yi) (1936, Chinese)

- Dimensions:Height: 96 in (243.84 cm)Width: 48 in (121.92 cm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:Santa Fe, NM

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU19121889343

About the Seller

4.9

Gold Seller

Premium sellers maintaining a 4.3+ rating and 24-hour response times

Established in 1966

1stDibs seller since 2015

103 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: <1 hour

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: Santa Fe, NM

- Return Policy

More From This Seller

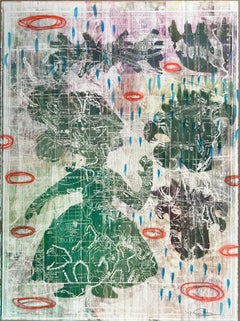

View AllKnowing Some History, mixed media monotype, by Melanie A Yazzie, Navajo, unique

By Melanie Yazzie

Located in Santa Fe, NM

Knowing Some History, mixed media monotype, by Melanie A Yazzie, Navajo, unique

As a printmaker, painter, and sculptor, my work draws upon my rich Diné (Navajo) heritage. The work I...

Category

2010s Contemporary Mixed Media

Materials

Pastel, Monotype

Equis 2, sculpture, by Jeffrey Maron, contemporary, textured, brown, horse

By Jeffrey Maron

Located in Santa Fe, NM

Equis 2, sculpture, by Jeffrey Maron, contemporary, textured, brown, horse

Category

2010s Contemporary Abstract Sculptures

Materials

Copper

Abstract Geometric, small abstract bronze, dark brown patina, life cast, marble

By Allan Houser

Located in Santa Fe, NM

Abstract Geometric, small abstract bronze, dark brown patina, life cast, marble

limited edition

Allan Houser (Haozous), Chiricahua Apache (1914-1994)

Selec...

Category

1980s Contemporary Abstract Sculptures

Materials

Marble, Bronze

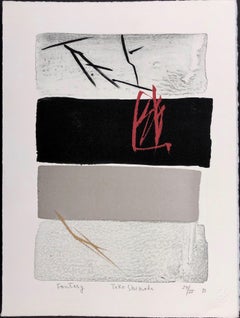

Fantasy, Japanese, limited edition lithograph, black, white, red, signed, titled

By Toko Shinoda

Located in Santa Fe, NM

Fantasy, Japanese, limited edition lithograph, black, white, red, signed, titled

Shinoda's works have been collected by public galleries and museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Brooklyn Museum and Metropolitan Museum (all in New York City), the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, the British Museum in London, the Art Institute of Chicago, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., the Singapore Art Museum, the National Museum of Singapore, the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, Netherlands, the Albright–Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, the Cincinnati Art Museum, and the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut.

New York Times Obituary, March 3, 2021 by Margalit Fox, Alex Traub contributed reporting.

Toko Shinoda, one of the foremost Japanese artists of the 20th century, whose work married the ancient serenity of calligraphy with the modernist urgency of Abstract Expressionism, died on Monday at a hospital in Tokyo. She was 107.

Her death was announced by her gallerist in the United States.

A painter and printmaker, Ms. Shinoda attained international renown at midcentury and remained sought after by major museums and galleries worldwide for more than five decades.

Her work has been exhibited at, among other places, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; the British Museum; and the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. Private collectors include the Japanese imperial family.

Writing about a 1998 exhibition of Ms. Shinoda’s work at a London gallery, the British newspaper The Independent called it “elegant, minimal and very, very composed,” adding, “Her roots as a calligrapher are clear, as are her connections with American art of the 1950s, but she is quite obviously a major artist in her own right.”

As a painter, Ms. Shinoda worked primarily in sumi ink, a solid form of ink, made from soot pressed into sticks, that has been used in Asia for centuries.

Rubbed on a wet stone to release their pigment, the sticks yield a subtle ink that, because it is quickly imbibed by paper, is strikingly ephemeral. The sumi artist must make each brush stroke with all due deliberation, as the nature of the medium precludes the possibility of reworking even a single line.

“The color of the ink which is produced by this method is a very delicate one,” Ms. Shinoda told The Business Times of Singapore in 2014. “It is thus necessary to finish one’s work very quickly. So the composition must be determined in my mind before I pick up the brush. Then, as they say, the painting just falls off the brush.”

Ms. Shinoda painted almost entirely in gradations of black, with occasional sepias and filmy blues. The ink sticks she used had been made for the great sumi artists of the past, some as long as 500 years ago.

Her line — fluid, elegant, impeccably placed — owed much to calligraphy. She had been rigorously trained in that discipline from the time she was a child, but she had begun to push against its confines when she was still very young.

Deeply influenced by American Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell, whose work she encountered when she lived in New York in the late 1950s, Ms. Shinoda shunned representation.

“If I have a definite idea, why paint it?,” she asked in an interview with United Press International in 1980. “It’s already understood and accepted. A stand of bamboo is more beautiful than a painting could be. Mount Fuji is more striking than any possible imitation.”

Spare and quietly powerful, making abundant use of white space, Ms. Shinoda’s paintings are done on traditional Chinese and Japanese papers, or on backgrounds of gold, silver or platinum leaf.

Often asymmetrical, they can overlay a stark geometric shape with the barest calligraphic strokes. The combined effect appears to catch and hold something evanescent — “as elusive as the memory of a pleasant scent or the movement of wind,” as she said in a 1996 interview.

Ms. Shinoda’s work also included lithographs; three-dimensional pieces of wood and other materials; and murals in public spaces, including a series made for the Zojoji Temple in Tokyo.

The fifth of seven children of a prosperous family, Ms. Shinoda was born on March 28, 1913, in Dalian, in Manchuria, where her father, Raijiro, managed a tobacco plant. Her mother, Joko, was a homemaker. The family returned to Japan when she was a baby, settling in Gifu, midway between Kyoto and Tokyo.

One of her father’s uncles, a sculptor and calligrapher, had been an official seal carver to the Meiji emperor. He conveyed his love of art and poetry to Toko’s father, who in turn passed it to Toko.

“My upbringing was a very traditional one, with relatives living with my parents,” she said in the U.P.I. interview. “In a scholarly atmosphere, I grew up knowing I wanted to make these things, to be an artist.”

She began studying calligraphy at 6, learning, hour by hour, impeccable mastery over line. But by the time she was a teenager, she had begun to seek an artistic outlet that she felt calligraphy, with its centuries-old conventions, could not afford.

“I got tired of it and decided to try my own style,” Ms. Shinoda told Time magazine in 1983. “My father always scolded me for being naughty and departing from the traditional way, but I had to do it.”

Moving to Tokyo as a young adult, Ms. Shinoda became celebrated throughout Japan as one of the country’s finest living calligraphers, at the time a signal honor for a woman. She had her first solo show in 1940, at a Tokyo gallery.

During World War II, when she forsook the city for the countryside near Mount Fuji, she earned her living as a calligrapher, but by the mid-1940s she had started experimenting with abstraction. In 1954 she began to achieve renown outside Japan with her inclusion in an exhibition of Japanese calligraphy at MoMA.

In 1956, she traveled to New York. At the time, unmarried Japanese women could obtain only three-month visas for travel abroad, but through zealous renewals, Ms. Shinoda managed to remain for two years.

She met many of the titans of Abstract Expressionism there, and she became captivated by their work.

“When I was in New York in the ’50s, I was often included in activities with those artists, people like Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Motherwell and so forth,” she said in a 1998 interview with The Business Times. “They were very generous people, and I was often invited to visit their studios, where we would share ideas and opinions on our work. It was a great experience being together with people who shared common feelings.”

During this period, Ms. Shinoda’s work was sold in the United States by Betty Parsons, the New York dealer who represented Pollock, Rothko and many of their contemporaries.

Returning to Japan, Ms. Shinoda began to fuse calligraphy and the Expressionist aesthetic in earnest. The result was, in the words of The Plain Dealer of Cleveland in 1997, “an art of elegant simplicity and high drama.”

Among Ms. Shinoda’s many honors, she was depicted, in 2016, on a Japanese postage stamp. She is the only Japanese artist to be so honored during her lifetime.

No immediate family members survive.

When she was quite young and determined to pursue a life making art, Ms. Shinoda made the decision to forgo the path that seemed foreordained for women of her generation.

“I never married and have no children,” she told The Japan Times in 2017. “And I suppose that it sounds strange to think that my paintings are in place of them — of course they are not the same thing at all. But I do say, when paintings that I have made years ago are brought back into my consciousness, it seems like an old friend, or even a part of me, has come back to see me.”

Works of a Woman's Hand

Toko Shinoda bases new abstractions on ancient calligraphy

Down a winding side street in the Aoyama district, western Tokyo. into a chunky white apartment building, then up in an elevator small enough to make a handful of Western passengers friends or enemies for life. At the end of a hall on the fourth floor, to the right, stands a plain brown door. To be admitted is to go through the looking glass. Sayonara today. Hello (Konichiwa) yesterday and tomorrow.

Toko Shinoda, 70, lives and works here. She can be, when she chooses, on e of Japans foremost calligraphers, master of an intricate manner of writing that traces its lines back some 3,000 years to ancient China. She is also an avant-garde artist of international renown, whose abstract paintings and lithographs rest in museums around the world. These diverse talents do not seem to belong in the same epoch. Yet they have somehow converged in this diminutive woman who appears in her tiny foyer, offering slippers and ritual bows of greeting.

She looks like someone too proper to chip a teacup, never mind revolutionize an old and hallowed art form She wears a blue and white kimono of her own design. Its patterns, she explains, are from Edo, meaning the period of the Tokugawa shoguns, before her city was renamed Tokyo in 1868. Her black hair is pulled back from her face, which is virtually free of lines and wrinkles. except for the gold-rimmed spectacles perched low on her nose (this visionary is apparently nearsighted). Shinoda could have stepped directly from a 19th century Meji print.

Her surroundings convey a similar sense of old aesthetics, a retreat in the midst of a modern, frenetic city. The noise of the heavy traffic on a nearby elevated highway sounds at this height like distant surf. delicate bamboo shades filter the daylight. The color arrangement is restful: low ceilings of exposed wood, off-white walls, pastel rugs of blue, green and gray.

It all feels so quintessentially Japanese that Shinoda’s opening remarks come as a surprise. She points out (through a translator) that she was not born in Japan at all but in Darien, Manchuria. Her father had been posted there to manage a tobacco company under the aegis of the occupying Japanese forces, which seized the region from Russia in 1905. She says,”People born in foreign places are very free in their thinking, not restricted” But since her family went back to Japan in 1915, when she was two, she could hardly remember much about a liberated childhood? She answers,”I think that if my mother had remained in Japan, she would have been an ordinary Japanese housewife. Going to Manchuria, she was able to assert her own personality, and that left its mark on me.”

Evidently so. She wears her obi low on the hips, masculine style. The Porcelain aloofness she displays in photographs shatters in person. Her speech is forceful, her expression animated and her laugh both throaty and infectious. The hand she brings to her mouth to cover her amusement (a traditional female gesture of modesty) does not stand a chance.

Her father also made a strong impression on the fifth of his seven children:”He came from a very old family, and he was quite strict in some ways and quite liberal in others.” He owned one of the first three bicycles ever imported to Japan and tinkered with it constantly He also decided that his little daughter would undergo rigorous training in a procrustean antiquity.

“I was forced to study from age six on to learn calligraphy,” Shinoda says, The young girl dutifully memorized and copied the accepted models. In one sense, her father had pushed her in a promising direction, one of the few professional fields in Japan open to females. Included among the ancient terms that had evolved around calligraphy was onnade, or woman's writing.

Heresy lay ahead. By the time she was 15, she had already been through nine years of intensive discipline, “I got tired of it and decided to try my own style. My father always scolded me for being naughty and departing from the traditional way, but I had to do it.”

She produces a brush and a piece of paper to demonstrate the nature of her rebellion. “This is kawa, the accepted calligraphic character for river,” she says, deftly sketching three short vertical strokes. “But I wanted to use more than three lines to show the force of the river.” Her brush flows across the white page, leaving a recognizable river behind, also flowing.” The simple kawa in the traditional language was not enough for me. I wanted to find a new symbol to express the word river.”

Her conviction grew that ink could convey the ineffable, the feeling, "as she says, of wind blowing softly.” Another demonstration. She goes to the sliding wooden door of an anteroom and disappears in back of it; the only trace of her is a triangular swatch of the right sleeve of her kimono, which she has arranged for that purpose. A realization dawns. The task of this artist is to paint that three sided pattern so that the invisible woman attached to it will be manifest to all viewers.

Gen, painted especially for TIME, shows Shinoda’s theory in practice. She calls the work “my conception of Japan in visual terms.” A dark swath at the left, punctuated by red, stands for history. In the center sits a Chinese character gen, which means in the present or actuality. A blank pattern at the right suggests an unknown future.

Once out of school, Shinoda struck off on a path significantly at odds with her culture. She recognized marriage for what it could mean to her career (“a restriction”) and decided against it. There was a living to be earned by doing traditional calligraphy:she used her free time to paint her variations. In 1940 a Tokyo gallery exhibited her work. (Fourteen years would pass before she got a second show.)War came, and bad times for nearly everyone, including the aspiring artist , who retreated to a rural area near Mount Fuji and traded her kimonos for eggs.

In 1954 Shinoda’s work was included in a group exhibit at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. Two years later, she overcame bureaucratic obstacles to visit the U.S.. Unmarried Japanese women are allowed visas for only three months, patiently applying for two-month extensions, one at a time, Shinoda managed to travel the country for two years. She pulls out a scrapbook from this period. Leafing through it, she suddenly raises a hand and touches her cheek:”How young I looked!” An inspection is called for. The woman in the grainy, yellowing newspaper photograph could easily be the on e sitting in this room. Told this, she nods and smiles. No translation necessary.

Her sojourn in the U.S. proved to be crucial in the recognition and development of Shinoda’s art. Celebrities such as actor Charles Laughton and John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet bought her paintings and spread the good word. She also saw the works of the abstract expressionists, then the rage of the New York City art world, and realized that these Western artists, coming out of an utterly different tradition, were struggling toward the same goal that had obsessed her. Once she was back home, her work slowly made her famous.

Although Shinoda has used many materials (fabric, stainless steel, ceramics, cement), brush and ink remain her principal means of expression. She had said, “As long as I am devoted to the creation of new forms, I can draw even with muddy water.” Fortunately, she does not have to. She points with evident pride to her ink stone, a velvety black slab of rock, with an indented basin, that is roughly a foot across and two feet long. It is more than 300 years old. Every working morning, Shinoda pours about a third of a pint of water into it, then selects an ink stick from her extensive collection, some dating back to China’s Ming dynasty. Pressing stick against stone, she begins rubbing. Slowly, the dried ink dissolves in the water and becomes ready for the brush. So two batches of sumi (India ink) are exactly alike; something old, something new. She uses color sparingly. Her clear preference is black and all its gradations. “In some paintings, sumi expresses blue better than blue.”

It is time to go downstairs to the living quarters. A niece, divorced and her daughter,10,stay here with Shinoda; the artist who felt forced to renounce family and domesticity at the outset of her career seems welcome to it now. Sake is offered, poured into small cedar boxes and happily accepted. Hold carefully. Drink from a corner. Ambrosial. And just right for the surroundings and the hostess. A conservative renegade; a liberal traditionalist; a woman steeped in the male-dominated conventions that she consistently opposed. Her trail blazing accomplishments are analogous to Picasso’s.

When she says goodbye, she bows. --by Paul Gray...

Category

1990s Contemporary Abstract Prints

Materials

Lithograph

Another Set of Monuments, walnut ink painting on paper, desert landscape, brown

Located in Santa Fe, NM

Another Set of Monuments, walnut ink painting on paper, desert landscape, brown

Helen Stanley’s sculptural paintings are beautifully drawn, realisticall...

Category

2010s Contemporary Landscape Paintings

Materials

Ink, Handmade Paper

Stone Messages, painting, Tony Abeyta, Navajo, dieties, red, yellow, brown

By Tony Abeyta

Located in Santa Fe, NM

Stone Messages, painting, Tony Abeyta, Navajo, dieties, red, yellow, brown

Category

1990s Contemporary Abstract Paintings

Materials

Canvas, Mixed Media, Oil

You May Also Like

Chinese ink painting made with thousands of numbers, natural black, brown

Located in Carballo, ES

Obsessive, meticulous, almost monastic, Kramer immerses us in a universe of graphic and sculptural repetitions. His drawings on kraft paper glued with rabbit glue recall both ancient...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Conceptual Portrait Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Ink, Handmade Paper

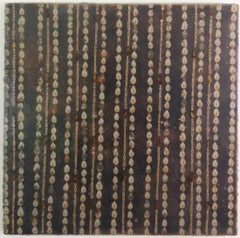

Wallpaper (Modern Mixed Media Black Encaustic Painting with Brown Seeds on Wood)

By Allyson Levy

Located in Hudson, NY

Foreign seeds and encaustic on wood panel

24 x 24 x 1.5 inches

This work on panel is being offered by Carrie Haddad Gallery, located in Hudson, NY.

This modern encaustic painting by...

Category

2010s Contemporary Abstract Paintings

Materials

Organic Material, Mixed Media, Encaustic, Wood Panel

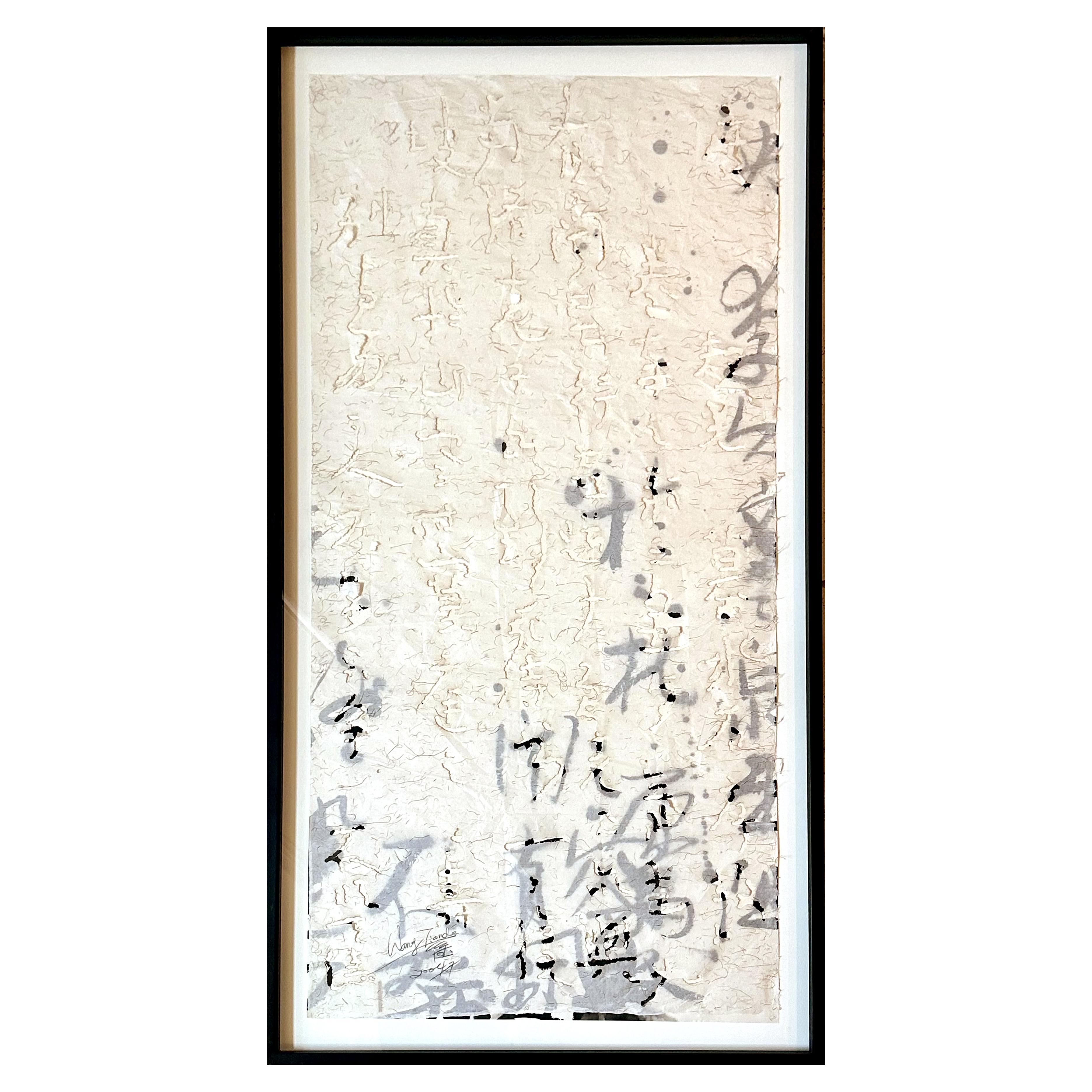

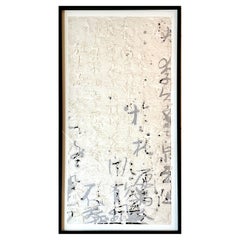

Chinese Contemporary Ink Art by Wang Tiande

Located in Atlanta, GA

Artist: Wang Tiande (Chinese b.1960)

Title: "Digital Series No.4 C07", 2004

Medium: Chinese ink on paper and cigarette burns

Signed and dated lower left Wang Tiande 2004.

Original gallery label on verso

Frame (wood shadow box under acylic): 52 3/4" x 25 3/4"

Provenance: Purchased from Michael Goedhuis, October 23, 2006

An important figure in the Chinese contemporary art scene, in the field of modern calligraphic art particularly, Wang Tiande was born in Shanghai in 1960. After graduating from the Chinese Painting Department at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in 1988, Wang received a doctoral degree in the calligraphy department of the same school. Currently, Wang is a professor at Shanghai Fudan University. His work is held in the permanent collection of many important museums across the globe, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the British Museum.

Known for his revival and reinterpretation of Chinese calligraphy and painting...

Category

Early 2000s Chinese Modern Contemporary Art

Materials

Acrylic, Wood, Paper

Cincuenta 5: abstract painting on handmade paper from India, black w/ flowers

By Antonio Puri

Located in Bryn Mawr, PA

This is a sumi ink, acrylic, and mixed media painting on paper in black (or charcoal gray) with subtle appearances of flowers, leaves, and a white medallion. It is a highly textured work on heavy, handmade khadi paper from India, hand torn for irregular edges. This painting can be displayed in any orientation - horizontally or vertically. This piece works especially in a series -- six pieces available, each listed separately. I will combine shipping for your savings on multiple purchases within this series.

Antonio Puri was born in Chandigarh, Punjab, India and raised in the Himalayas around Buddhist monks before studying at the Academy of Art in San Francisco, Coe College, and the University of Iowa. He established his studio in Philadelphia where he practiced for many years before relocating to Bogotá, Colombia. During this time, Puri completed several artist residencies all over the world, including in New York, Hungary, Bulgaria, Colombia, South Africa, Serbia, Mauritius, India, Denmark, Trinidad and Tobago, and Romania. Puri’s range of geographical and cultural experiences are embedded in his work, where he commonly explores the relationships between his eastern and western cultural connections.

Puri has exhibited his work all over the world, including at the Museo de Arte del Tolima in Colombia; Sundaram Tagore Gallery Singapore; Government Museum and Art Gallery Chandigarh, India; Art Depot, Austria; La Cometa Gallery, Bogota; Museo Casa Conde Rul, Mexico; The Guild, NY; Nu Art...

Category

2010s Abstract Abstract Paintings

Materials

Paper, Sumi Ink, Mixed Media, Acrylic

"Delivered and Discarded (positives) #2" wall hanging ink and Tyvek assemblage

By Yoonmi Nam

Located in Philadelphia, PA

"Delivered and Discarded (positives) #2" is an original wall-hanging piece by Yoonmi Nam. This piece is made from the flattening out packing boxes that the artist traces to depict t...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Abstract Drawings and Waterco...

Materials

Found Objects, Sumi Ink, Synthetic Paper

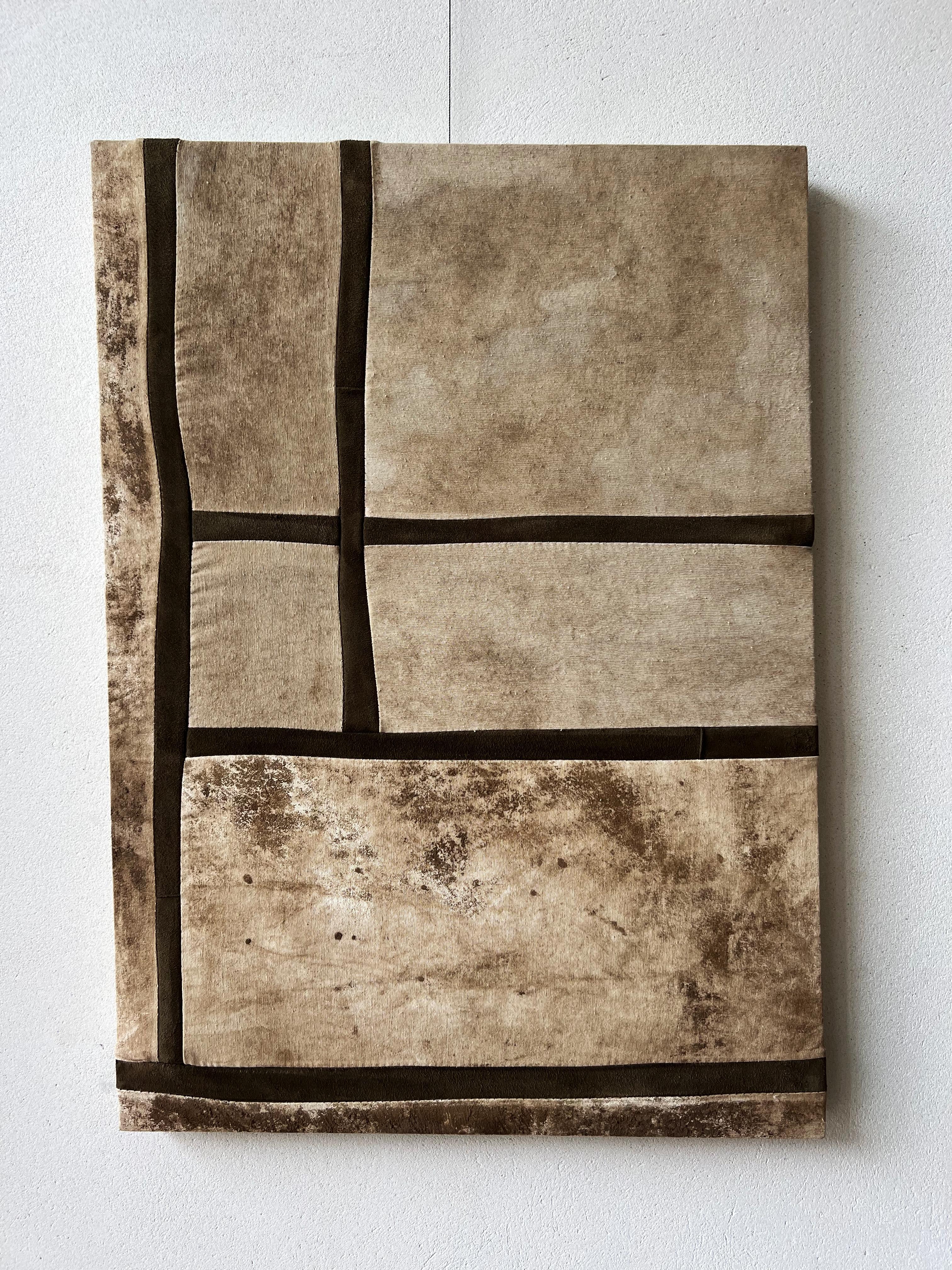

Art Povera painting made with leather and wood. Cartography, aerial map, brown.

Located in Carballo, ES

TUSET (1997, A Coruña) buries. He presents his latest series using patchwork, with paintings that have spent a year underground and leather. What emerges is an eroded map, a surface ...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Landscape Paintings

Materials

Leather, Wood, Cotton Canvas