Items Similar to Life Magazine Art Deco Showgirls Cartoon

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 14

BARBARA SHERMUNDLife Magazine Art Deco Showgirls Cartoon1934

1934

About the Item

Barbara Shermund (1899-1978). Showgirls Cartoon for Life Magazine, 1934. Ink, watercolor and gouache on heavy illustration paper, matting window measures 16.5 x 13 inches; sheet measures 19 x 15 inches; Matting panel measures 20 x 23 inches. Signed lower right. Very good condition with discoloration and toning in margins. Unframed.

Provenance: Ethel Maud Mott Herman, artist (1883-1984), West Orange NJ.

For two decades, she drew almost 600 cartoons for The New Yorker with female characters that commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony.

In the mid-1920s, Harold Ross, the founder of a new magazine called The New Yorker, was looking for cartoonists who could create sardonic, highbrow illustrations accompanied by witty captions that would function as social critiques.

He found that talent in Barbara Shermund.

For about two decades, until the 1940s, Shermund helped Ross and his first art editor, Rea Irvin, realize their vision by contributing almost 600 cartoons and sassy captions with a fresh, feminist voice.

Her cartoons commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony, using female characters who critiqued the patriarchy and celebrated speakeasies, cafes, spunky women and leisure. They spoke directly to flapper women of the era who defied convention with a new sense of political, social and economic independence.

“Shermund’s women spoke their minds about sex, marriage and society; smoked cigarettes and drank; and poked fun at everything in an era when it was not common to see young women doing so,” Caitlin A. McGurk wrote in 2020 for the Art Students League.

In one Shermund cartoon, published in The New Yorker in 1928, two forlorn women sit and chat on couches. “Yeah,” one says, “I guess the best thing to do is to just get married and forget about love.”

“While for many, the idea of a New Yorker cartoon conjures a highbrow, dry non sequitur — often more alienating than familiar — Shermund’s cartoons are the antithesis,” wrote McGurk, who is an associate curator and assistant professor at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. “They are about human nature, relationships, youth and age.” (McGurk is writing a book about Shermund.

And yet by the 1940s and ’50s, as America’s postwar focus shifted to domestic life, Shermund’s feminist voice and cool critique of society fell out of vogue. Her last cartoon appeared in The New Yorker in 1944, and much of her life and career after that remains unclear. No major newspaper wrote about her death in 1978 — The New York Times was on strike then, along with The Daily News and The New York Post — and her ashes sat in a New Jersey funeral home for nearly 35 years until they were claimed by a descendant in search of information about her.

Barbara Shermund was born on June 26, 1899, in San Francisco. Her father, Henry Shermund, was an architect; her mother, Fredda Cool, a sculptor. Barbara displayed a knack for illustrating at a young age, and her parents encouraged her to explore her passion. She published her first cartoon when she was 8, in the children’s section of The San Francisco Chronicle.

Shermund’s mother died in 1918 in the Spanish flu pandemic. Some years later, her father married a woman 31 years his junior and eight years younger than Barbara. As her father and his new wife went on to build their own family, Barbara became estranged from them.

She attended the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) to study printmaking and painting and regularly won awards.

She moved to New York City in her mid-20s to seek an independent life while pursuing her artistic ambitions, finding work creating cover art, cartoons and illustrations for magazines like Esquire, Life and Collier’s.

She is believed to have met Harold Ross and Rea Irvin through mutual connections from her studies and in the magazine industry. Her contributions to The New Yorker included about nine cover illustrations as well as spot illustrations and section mastheads that helped set the magazine’s visual tone.

Her perspective was influenced by her intersection with profound historical moments: In addition to surviving the Spanish flu pandemic, Shermund lived through World War I and the suffrage movement.

One of her cartoons from the 1920s, after women won the right to vote, depicted two men in tuxedos smoking by a grand fireplace, with one saying in the caption, “Well, I guess women are just human beings, after all.”

In 1943, Esquire magazine sent Shermund to the Hollywood set of the musical comedy “Du Barry Was a Lady” to sketch actresses performing in an I Love an Esquire Girl sequence. She created as well a promotional poster for the film, starring Red Skelton and Lucille Ball.

She also took on advertising commissions at a time when women were rare in that industry, illustrating ads for companies like Pepsi-Cola, Ponds, Philips 66 and Frigidaire.

From 1944 until about 1957, she produced Shermund’s Sallies, a syndicated cartoon panel for Pictorial Review, the arts and entertainment section of Hearst’s many Sunday newspaper.

Shermund lived out her last years drawing at her home in Sea Bright, N.J., and swimming at a beach nearby. She died on Sept. 9, 1978, at a nursing home in Middletown, N.J.

“The women she drew and the captions she wrote showed us women who were not afraid of making fun of men, and showed us what it was really like to be a woman,” Liza Donnelly, a cartoonist and writer at The New Yorker, said in an interview. “Shermund’s women had humor and guts, just like what I imagine the artist had herself.”

Perhaps one of Shermund’s most striking pieces is indicative of her irreverent and fearless spirit in life: A young girl sits on the lap of a paternal figure and says, “Please, tell me a story where the bad girl wins!”

- Creator:BARBARA SHERMUND (1899 - 1978, American)

- Creation Year:1934

- Dimensions:Height: 15 in (38.1 cm)Width: 19 in (48.26 cm)Depth: 0.01 in (0.26 mm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:Wilton Manors, FL

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU245212291292

About the Seller

4.9

Gold Seller

These expertly vetted sellers are highly rated and consistently exceed customer expectations.

Established in 2007

1stDibs seller since 2015

326 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 9 hours

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Ships From: Wilton Manors, FL

- Return PolicyA return for this item may be initiated within 7 days of delivery.

More From This SellerView All

- Art Deco Spanish Woman Fashion IllustrationLocated in Wilton Manors, FLElegant and glamorous fashion illustration from the 1920's, Original signed gouache painting on paper. Monogrammed V.S. lower right. Site: 10"x 7.75" Frame: 19.25"x 17"Category

1920s Art Deco Figurative Paintings

MaterialsPaper, Gouache

- Coronel Retirado y Su Amante Esposa (Cuban Artist)By Felipe OrlandoLocated in Wilton Manors, FLFelipe Orlando (Cuban-Mexican, 1911-2001). Coronel Retirado y su Amante Esposa, ca. 1970. Ink and gouache on paper with heavily built up layers of textured ground. Measures 13 1/4 x 18 3/8 inches. Signed lower left. Original label affixed on verso. Excellent condition. Unframed. An anthropologist as well as a painter and engraver, Orlando, whose full name was Felipe Orlando Garcia Murciano, studied at the University of Havana and at the painting workshop of Jorge Arche and Víctor Manuel. He was a founding member of the Asociación de Pintores y Escultores de Cuba (APEC) and a professor at the Universidad de las Américas and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, both in Mexico City. His style is influenced by the Afro-Cuban movement and pre-columbian art...Category

1970s Abstract Abstract Paintings

MaterialsInk, Gouache

- Fancy Department Store Satirical CartoonLocated in Wilton Manors, FLBarbara Shermund (1899-1978). Fancy Department Store Satirical Cartoon, ca. 1930's. Ink, watercolor and gouache on heavy illustration paper, panel measures 19 x 15 inches. Signed lower right. Very good condition. Unframed. Provenance: Ethel Maud Mott Herman, artist (1883-1984), West Orange NJ. For two decades, she drew almost 600 cartoons for The New Yorker with female characters that commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony. In the mid-1920s, Harold Ross, the founder of a new magazine called The New Yorker, was looking for cartoonists who could create sardonic, highbrow illustrations accompanied by witty captions that would function as social critiques. He found that talent in Barbara Shermund. For about two decades, until the 1940s, Shermund helped Ross and his first art editor, Rea Irvin, realize their vision by contributing almost 600 cartoons and sassy captions with a fresh, feminist voice. Her cartoons commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony, using female characters who critiqued the patriarchy and celebrated speakeasies, cafes, spunky women and leisure. They spoke directly to flapper women of the era who defied convention with a new sense of political, social and economic independence. “Shermund’s women spoke their minds about sex, marriage and society; smoked cigarettes and drank; and poked fun at everything in an era when it was not common to see young women doing so,” Caitlin A. McGurk wrote in 2020 for the Art Students League. In one Shermund cartoon, published in The New Yorker in 1928, two forlorn women sit and chat on couches. “Yeah,” one says, “I guess the best thing to do is to just get married and forget about love.” “While for many, the idea of a New Yorker cartoon conjures a highbrow, dry non sequitur — often more alienating than familiar — Shermund’s cartoons are the antithesis,” wrote McGurk, who is an associate curator and assistant professor at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. “They are about human nature, relationships, youth and age.” (McGurk is writing a book about Shermund. And yet by the 1940s and ’50s, as America’s postwar focus shifted to domestic life, Shermund’s feminist voice and cool critique of society fell out of vogue. Her last cartoon appeared in The New Yorker in 1944, and much of her life and career after that remains unclear. No major newspaper wrote about her death in 1978 — The New York Times was on strike then, along with The Daily News and The New York Post — and her ashes sat in a New Jersey funeral home...Category

1930s Realist Figurative Paintings

MaterialsInk, Gouache

- Same Old Story (Brooklyn Dodgers & St. Louis Cardinals Illustration)Located in Wilton Manors, FLBill Crawford (1913-1982). Original illustration artwork depicting teams as they advance to the World Series. Depicted are representations of the St. Louis Cardinals and The Brooklyn...Category

1940s Realist Figurative Paintings

MaterialsPaper, Charcoal, Ink, Gouache, Pencil

- Sailors at Cafe du GlobeBy Charles RocherLocated in Wilton Manors, FLCharles Rocher (1890-1962. Sailors, ca. 1920s. Gouache on paper. Sheet measures 19 x 25 inches. Considerable damage and loss as depicted. Signed lower left.Category

1920s Realist Figurative Paintings

MaterialsGouache

- Mother and ChildLocated in Wilton Manors, FLBeautiful original painting by French artist, Alexandre de Valentini (1787-1887). Pencil and gouache on paper, 14 x 18.5 inches; 19 x 23.5 inches matted. Signed and dated with Paris...Category

Mid-19th Century Academic Interior Paintings

MaterialsPencil, Gouache

You May Also Like

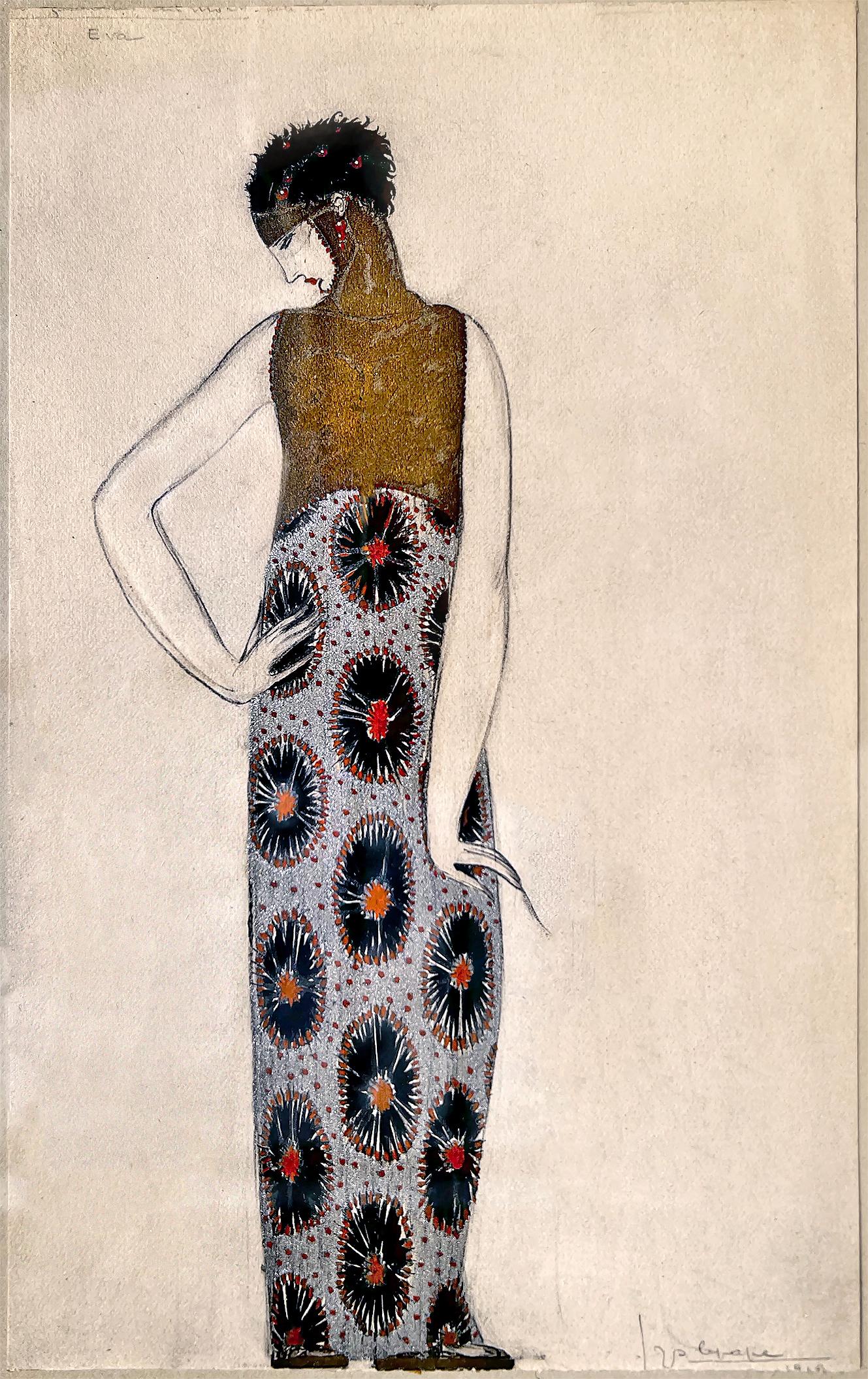

- Art Deco Costume Design - EvaBy Georges LepapeLocated in Miami, FLThe paper in some of these photos looks overly textured due to the sharpness of the high-res digital camera. In person, with the human eye, the paper looks reasonably smooth with out blemishes. For this fashion illustration, Georges Lepape paints a stunning abstract pattern for the subject dress that is repeated in her hair. The work represents an early use of metallic paint, with silver metallic in the dress and bronze metallic in the blouse. Lepape's highly detailed drawing becomes more evident the closer you look. It's quite amazing how deftly he rendered facial feature on such a small scale. "Eva" 1918 Gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper Signed and dated, lower right: '1918' Inscribed, verso: "Costume for L'enfantement du mort, (miracle en pourpre, et or.). Devised by Marcel L'Herbier and performed at the Théatre Edouard VII and the Comédie des Champs-Elysées, 1919" Provenance: Ex-collection Lucien...Category

1910s Art Deco Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsInk, Gouache, Paper, Watercolor, Pencil

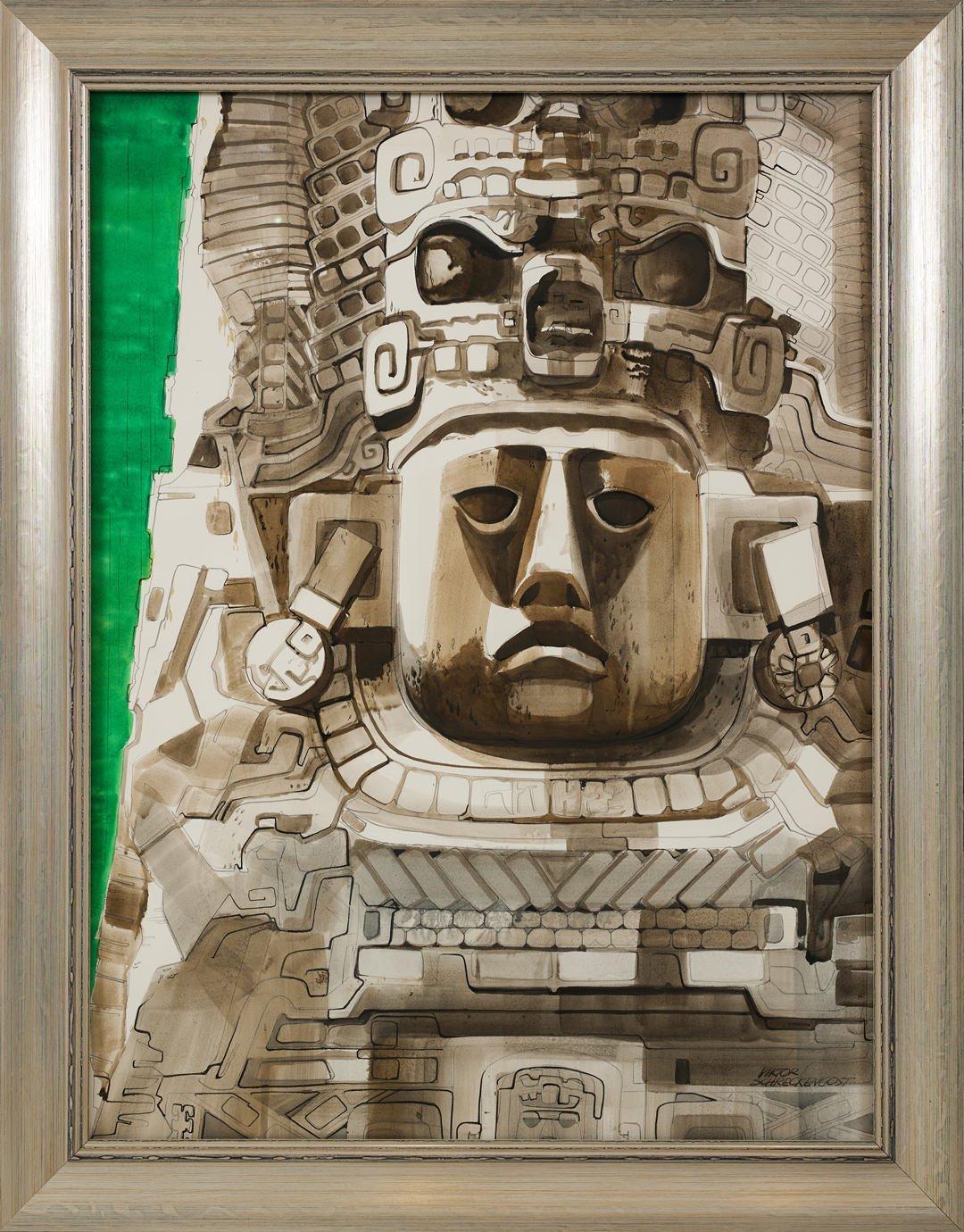

- Mayan, Large 20th Century Watercolor, Viktor SchreckengostBy Viktor SchreckengostLocated in Beachwood, OHViktor Schreckengost (American, 1906-2008) Mayan Watercolor heightened with gouache over pencil on paper Signed lower right 39 x 29 inches 45.5 x 35.5 inches, framed Registered with The Viktor Schreckengost foundation, stock no. 6891 The son of a commercial potter in Sebring, Ohio, Viktor Schreckengost learned the craft of sculpting in clay from his father. In the mid-1920s, he enrolled at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art, or CIA) to study cartoon making, but after seeing an exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art he changed his focus to ceramics. Upon graduation in 1929, he studied ceramics in Vienna, Austria, where he began to build a reputation, not only for his art, but also as a jazz saxophonist. A year later, at the age of 25, he became the youngest faculty member at the CIA. In 1931, Schreckengost won the first of several awards for excellence in ceramics at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and his works were shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, and elsewhere. By the mid-1930s, Schreckengost had begun to pursue his interest in industrial design. For American Limoges...Category

20th Century Art Deco Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsWatercolor, Gouache

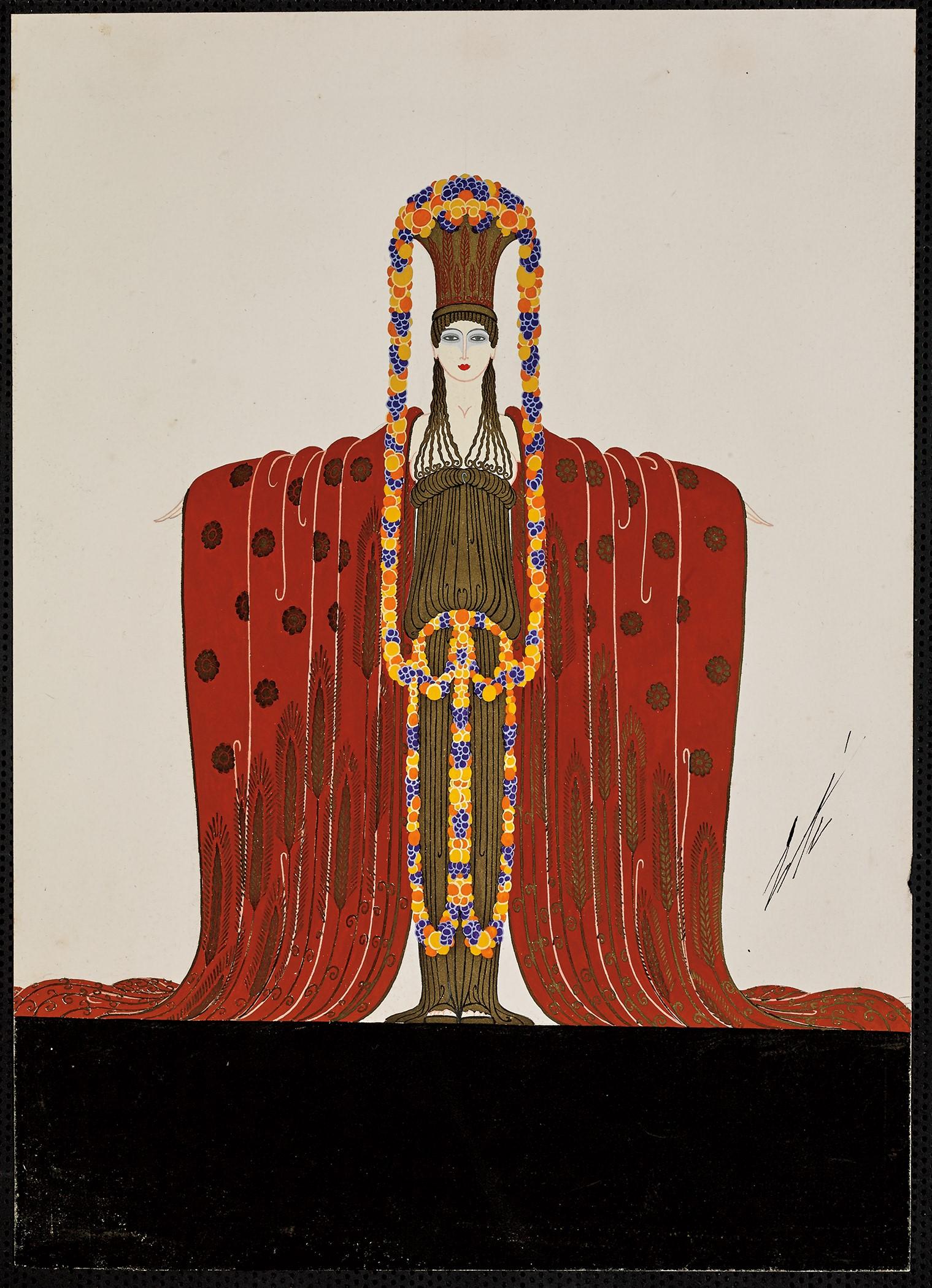

- Demeter (Les Idoles, Folies Bergère), 1924By ErtéLocated in Greenwich, CTDéméter from Les Idoles, Folies Bergère was created in 1924 and is a gouache on paper measuring approximately 14.75 x 10.5 inches. Framed in a custom, closed-corner Art Deco...Category

20th Century Art Deco Paintings

MaterialsGouache, Paper

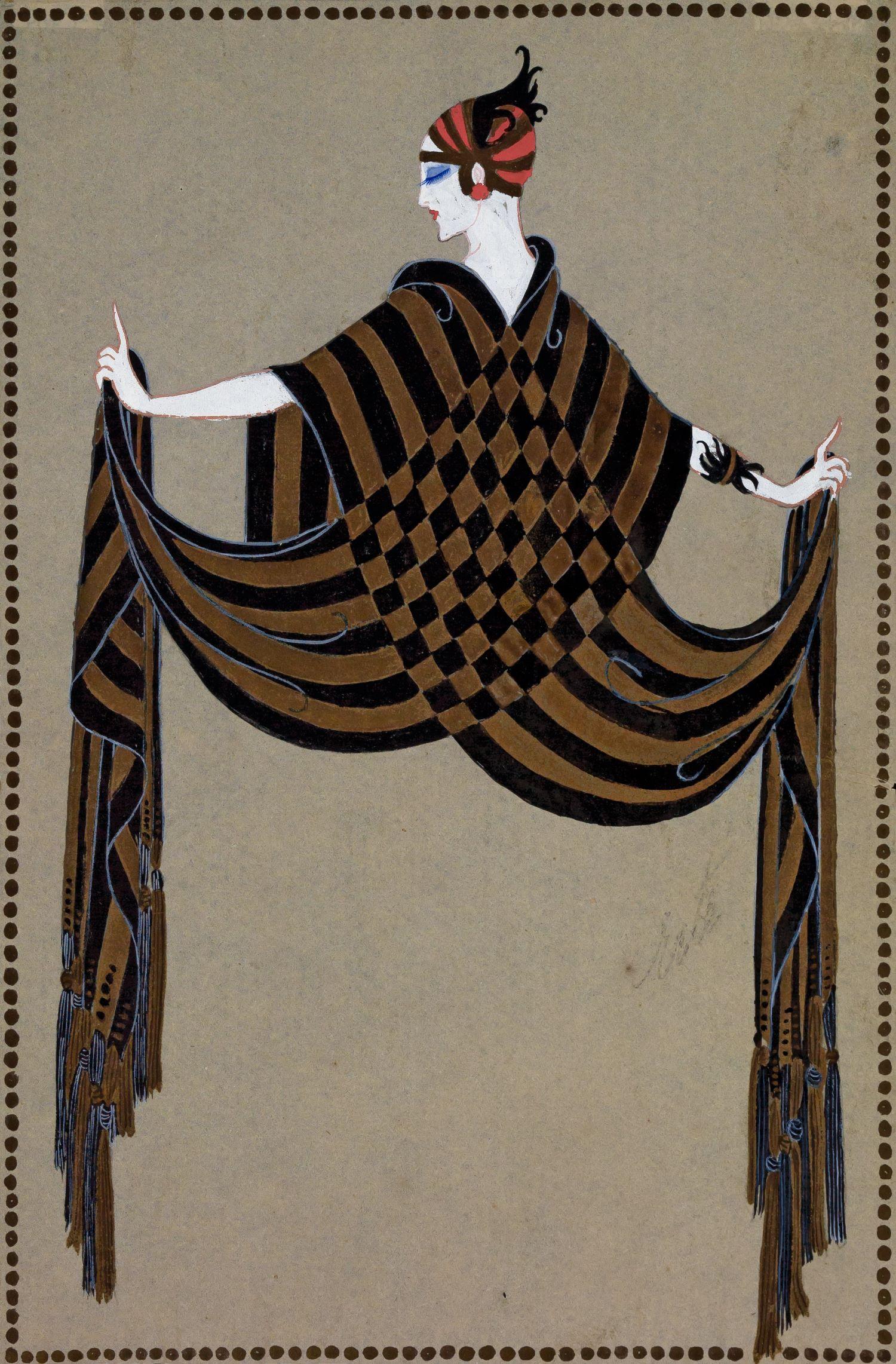

- The Treasures of Indo-China, 1922By ErtéLocated in Greenwich, CTThe Treasures of Indo-China, created in 1922, is a gouache on paper, 15 x 11.25 inches and framed in a custom, closed-corner Art Deco frame. Signed rec...Category

20th Century Art Deco Paintings

MaterialsGouache, Paper

- Untitled Fashion Design, 1920By ErtéLocated in Greenwich, CTUntitled (Fashion Design) was created for Harper's Bazar and appeared in the February, 1920 edition of the magazine. This is a gouache painting on tissue paper measuring approximately 10 x 6.5 inches and framed in a custom, closed-corner Art Deco...Category

20th Century Art Deco Paintings

MaterialsGouache, Paper

- Martha, Act I (Chicago Opera), 1925By ErtéLocated in Greenwich, CTMartha, Act I (Chicago Opera) from 1925 is a gouache on paper measuring approximately 9 x 7 inches and framed in a custom, closed-corner frame. Signed recto 'Erté' mid-right and stamped with Erte's Villa Excelsior block stamp and 'Composition originale' verso. Annotated in fountain pen verso 'No 659 Martha I acte Pour Madame Ganna Walska...Category

20th Century Art Deco Paintings

MaterialsGouache, Paper

Recently Viewed

View AllMore Ways To Browse

Red Skelton

Red Skelton Art

1940s Tuxedo

Vintage Forget Me Not Drawing

Red Skelton Paintings

Pepsi Poster

Eric Pfeiffer

Garry Morrow

Gian Paolo Dulbecco

Gropper Beach

Harold Cohn

Hock Tee Tan

Irish Painter Green Abstract California Beach

Jan Cossiers

Jean Albert Pougny

Jean Charles Castel

Jean Claude Mobius

Jeff Legg