Items Similar to Hellenistic Grotesque Theatre Mask of Maccus

Video Loading

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 10

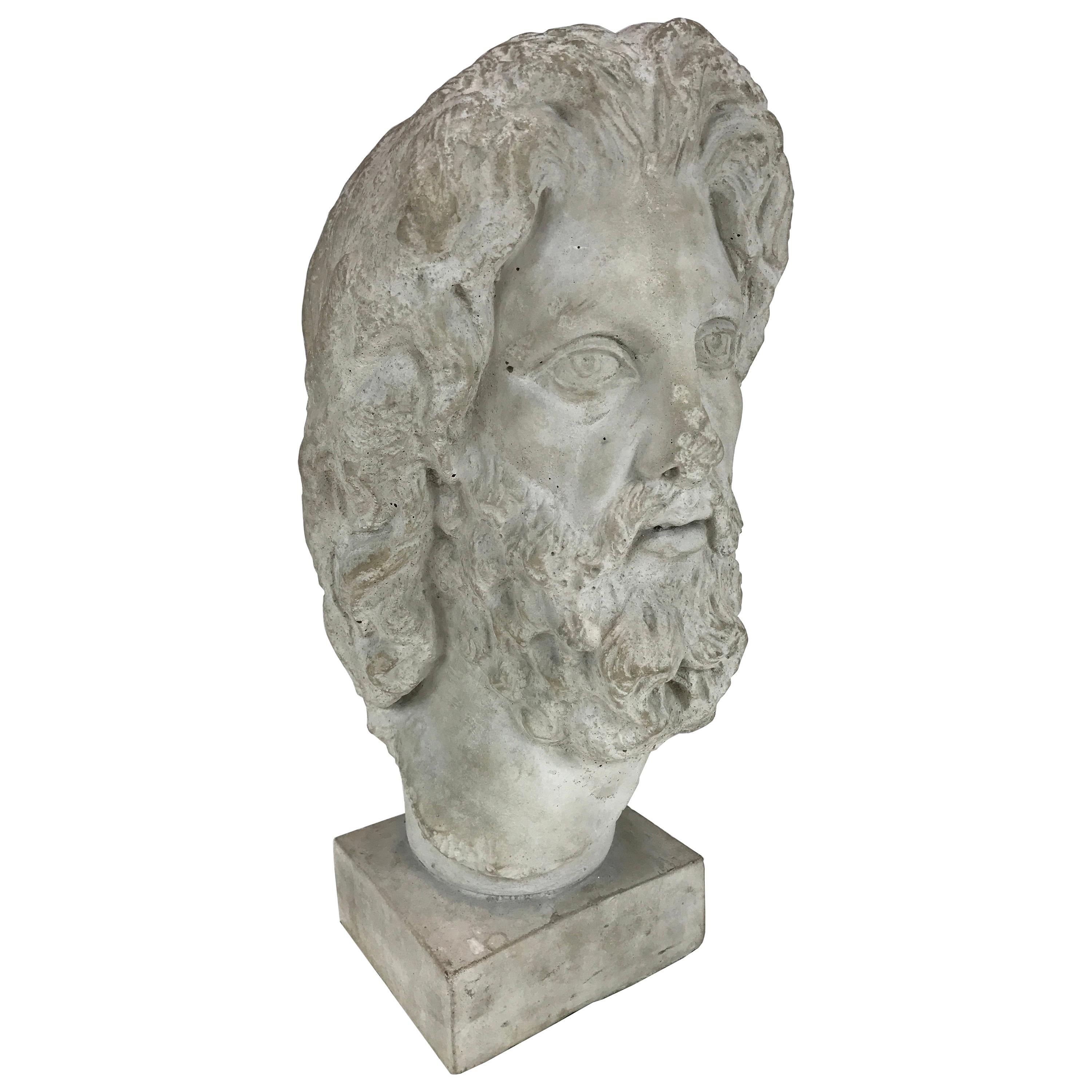

Hellenistic Grotesque Theatre Mask of Maccus

About the Item

Grotesque theatrical mask of Maccus

Late Hellenistic or Early Imperial period, circa 1st century B.C. – 1st century A.D., likely from Southern Italy.

Terracotta with remains of pink and white pigment

Measure: Height: 20 cm.

With old label reading '‘n° 45''

This highly expressive terracotta mask is incredibly well-preserved, perhaps the best of all known masks of the Maccus type. It depicts a man with grotesque, comically deformed features. The face is broad with protruding ears, the hook-shaped nose is large and crooked, and the grimacing, gaping mouth reveals the figure’s bottom teeth. The eyebrows are frowning, accentuating the wrinkled forehead, and the man has a hunch on top of his bald skull. Holes have been pierced through the forehead and on each side of the mask, by which it would once have been attached, to a plinth or wall, as a hanging decorative object.

Under the influence of Greek settlers, a vibrant theatre tradition was established in and around the Southern Italian peninsula from at least the fifth century B.C. The comic genres focusing on social satire and mockery were particularly popular amongst both Greeks and native Italic people. In the Greek colonies, a new genre of farce was developed in the 4th century B.C. - the Phlyax plays, a form of mythological burlesque blending figures from the Greek pantheon with tropes borrowed from Athenian New Comedy. One of the most popular characters was Maccus, a bald, hunchbacked, crooked-nosed, and large-eared peasant, driven and derided by greed, whose physical description is reminiscent of the present mask. It was this genre of comedy that, through contact between the Southern Italian Greeks and their neighbours to the North, would later become beloved by the Romans.

It is important to note that stage performers did not wear masks in terracotta. Rather, they wore masks fashioned out of perishable materials such as wood, linen, or leather. Terracotta masks such as this one were modelled after these and deposed in sanctuaries or used as garden decoration. The use of masks as decorative ornaments testifies to the popularity of the dramatic arts in Rome and a strong aesthetic appreciation for theatre costumes. Indeed, props such as masks strongly enhanced the audience’s visual and aesthetic experience. As such, they were undoubtedly part of why farces were so loved by the public and thus became iconic elements of Roman public and cultural life. Depictions of theatrical scenes, actors, and masks can be found across the Roman arts, from sculptures to mosaics, frescoes, and reliefs, decorating both private and public buildings throughout the Empire.

Provenance:

- From the collection of Louis-Gabriel Bellon (1819-1899), Saint-Nicolas-lez- Arras and Rouen, thence by descent.

- Dimensions:Height: 7.88 in (20 cm)Diameter: 7.49 in (19 cm)

- Style:Classical Roman (Of the Period)

- Materials and Techniques:

- Place of Origin:

- Period:

- Date of Manufacture:circa 1st Century B.C.-1st Century A.D.

- Condition:

- Seller Location:London, GB

- Reference Number:

About the Seller

5.0

Recognized Seller

These prestigious sellers are industry leaders and represent the highest echelon for item quality and design.

Established in 2008

1stDibs seller since 2014

100 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 8 hours

Associations

LAPADA - The Association of Arts & Antiques DealersInternational Confederation of Art and Antique Dealers' AssociationsThe British Antique Dealers' Association

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Ships From: London, United Kingdom

- Return PolicyA return for this item may be initiated within 14 days of delivery.

More From This SellerView All

- Ancient Greek Hellenistic Bronze Statuette of SatyrLocated in London, GBBeautifully cast statuette of a satyr, Greek, Hellenistic Period, 3rd-2nd Century BC, solid cast bronze The present work is a wonderful example of the finest Hellenistic style. The ...Category

Antique 15th Century and Earlier Greek Classical Greek Figurative Sculpt...

MaterialsBronze

- Exceptional Egyptian Sarcophagus MaskLocated in London, GBExceptionally Fine Wooden Sarcophagus Mask Third Intermediate Period, 21st Dynasty, circa 1069-945 BC. Acacia wood, rosewood, hippopotamus ivory Masterfully carved from a single piece of fine-grained hardwood, the present mask is characteristic of the most exquisite funerary art made during the 21st Dynasty, and was probably commissioned for a particularly high-ranking individual. The oval face displays a gently smiling mouth with full, outlined lips, furrows at the corners and a bow-shaped philtrum. The straight nose with rounded nostrils, the cheeks full and fleshy and the large, almond shaped eyes with heavy lids and tapering cosmetic lines, set below long, sweeping eyebrows. Social collapse across the Mediterranean in the Late Bronze Age meant that the 21st Dynasty in Egypt was a period of great turmoil. Trade routes were disrupted, governments collapsed, and mass migration occurred. Economic scarcity meant that traditional funerary practices in Egypt were also affected, with a lack of material and financial resources leading to the reuse of preexisting material. As a result, during the 21st Dynasty, 19th and 20th Dynasty coffins changed ownership rapidly and were heavily recycled for new purposes. Tombs were also unmarked allowing them to be shared by many people. These new practices brought forth a shift in the understanding of funerary paraphernalia. No longer important objects owned forever by the deceased, they were now simply seen as short-term transformative devices, whose symbolic and ritualistic meaning could be appropriated for others. However, paradoxically, the art of coffin-making also reached new heights during this period, and many of the richly dec- orated “yellow” coffins, characteristic of the 21st Dynasty, are remarkable works of art in their own right. Indeed, knowing that coffins were being reused throughout Egypt, the Egyptian élite set themself apart by commissioning lavish sarcophagi decorated with the images and texts meant to help guide them to the afterlife, and which would otherwise have adorned the tomb walls. As coffins were the chief funerary element which now identified the dead and allowed them a physical presence in the world of the living, their quality and appearance were of the utmost importance. The traditional coffin ensemble was made of three parts: a wooden mummy cover, which laid directly atop the mummy, an inner coffin, and an outer coffin, both made of a lid and case. Additional decorative elements, such as masks, were carved out separately and later glued or pegged to the lids. After the completion of the painted decoration, the sarcophagus was covered in a varnish to give it its yellow colour. Gilding was sometimes used for the coffins of the high priests’ families, notably on parts representing naked skin, such as the face mask. However, some of the élite tactically avoided gilding altogether as to ensure that their coffin would not be looted. When manufacturing the inner and outer coffins, particular attention was paid to the woodwork. Displaying the skill of the carpenter, this type of funerary art has largely remained unparalleled throughout Egyptian history. The principal wood used to craft the present mask is Acacia nilotica. The evergreen Egyptian acacia was considered sacred and said to be the tree of life, the birthplace of the god Horus, as well as symbolic of Osiris, the god of the dead and resurrection. The modelling of the face in the wood is superb, but the inlays also help mark this mask out as exceptional. Inlaid eyes and eyebrows were extremely rare and reserved to the finest and most expensive coffins. Traditionally, eyes were made of calcite, obsidian, or quartz, and eyebrows of coloured glass paste or bronze. Here, the pupils, eyebrows, and cosmetic lines are inlaid with Dalbergia melanoxylon, a rare type of wood which belongs to the rosewood genus. In antiquity, however, it was known as Ebony of the Pharaohs, from the Egyptian word “hbny”, meaning dark timber, because of its black, lustrous appearance. An extremely dense and hard wood requiring significant skill to work with, ebony was a luxury material highly coveted by the pharaohs themselves, to make furniture, decorative and funerary objects. The wood was imported with great effort from the southern Land of Punt, most likely modern Sudan, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Eritrea, alongside other luxury goods such as gold and ivory. A magnificent ebony throne, recovered in the tomb of King Tutankhamun, illustrates the incredible aesthetic potential of this material and why it was so highly valued by Egyptian royalty. Only élite members of Egyptian society could have afford- ed Ebony of the Pharaoh inlays for their funerary mask. The sclerae on the present piece were once both inlaid with hippopotamus ivory. Whiter than elephant ivory, this type of ivory is also denser, and more difficult to carve. The use of this luxury material, reputed for its gleaming appearance, enhances the lifelikeness of the eyes. For the Egyptians, hippopotamus ivory was imbued with magic powers. The hippopotamus was indeed both feared and venerated due to its aggressive behaviour. Whilst the male hippopotamus was associated with danger and chaos, the female was benevolent and invoked for protection, especially of the house and of mothers and their children, through the hippopotamus goddess Tawaret. Thus, not only was hippopotamus ivory used as an inlay and to make practical objects, such as combs and clappers, but it was also used to make talismans like apotropaic wands or knives. Made during a time of scarcity where few could afford made-to-order coffins, the present mask could have only belonged to one of the highest-ranking individuals in society. Undoubtedly one of the finest Egyptian coffin...Category

Antique 15th Century and Earlier Egyptian Egyptian Figurative Sculptures

MaterialsFruitwood, Hardwood

- Roman Portrait Bust of a Noble WomanLocated in London, GBRoman miniature bust of a noble woman, carved marble, Severan Dynasty, c. 225 A.D. Rare and particularly elegant ‘wig portrait’ of a noble woman, belonging to the early 3rd Century - a style distinctive of Severan Dynasty female portrait busts, in which part of the head has been chiselled away to allow for the addition of a separate hairpiece, in many cases from a darker material, in order to create an almost painterly effect, in the interplay of different coloured stones. The degree of naturalism and emotional depth achieved in a piece of such a small scale implies a sculptor of great talent. The subtle parting of the lips, in combination with her upturned, vacant gaze and tired eyes, conveys a pensive mood, and even a quiet melancholy. A woman strolls the town in thick wigs bought with gold, Then buys new hair to complement the old. And having bought, she doesn’t blush! Right there she buys, Before Alcides’ and the Muses’ eyes. (Ovid, Ars Amatoria, III, 161-168) The fashion of wig-wearing in this period, as well as its emulation in the wig portrait bust, is widely attributed to Julia Domna...Category

Antique 15th Century and Earlier Italian Classical Roman Busts

MaterialsMarble

- Roman Marble Statuette of JupiterLocated in London, GBRoman Marble Fragment of jupiter Circa 2nd-3rd Century A.D. Measure: Height: 19.7 cm This beautiful Roman fragmentary statuette depicts Jupiter, the king of the gods, here recognisable from his two chief attributes, the eagle with outstretched wings - according the Pseudo-Hyginus, singled out by Jupiter because ''it alone, men say, strives to fly straight into the rays of the rising sun'' - and the base of the scepter, which remains at the side of the left foot, an aspect likely borrowed from the statue of Zeus at Olympia, once one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Though much of the original piece has been lost, the subtle anatomical detail in the feet mark this out as a piece of exceptional quality, and the work of an artist of particular talent and patience - as Johann Winckelmann once said of the famous Belvedere Torso, ''if you contemplate this with a quiet eye [...] the god will at once become visible in this stone.'' This fragment once caught the eye of Henry Howard, 4th Earl of Carlisle (1694-1758), a Knight of the Garter and among the most prolific collectors of his day. The piece, acquired during his travels to Rome, was proudly displayed on an alcove of the Western Staircase of Castle Howard...Category

Antique 15th Century and Earlier Italian Classical Roman Figurative Scul...

MaterialsMarble

- Roman Marble Head of SophoclesLocated in London, GBRoman Marble Head of Sophocles Circa 1st-2nd Century Marble This fine Roman marble head preserves the proper left side of the face of a middle-aged man, with broad nose, soft lips, and bearded chin. The short beard and sideburns have been finely carved with a flat chisel, to render the soft, wavy strands of hair. The cheekbone, undereye, and nasolabial folds have been delicately modelled in the marble by a skilled hand. In a letter from 1975, the former director of Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, suggested that the head could depict the Ancient Greek tragedian Sophocles. Few figures in the Classical world stand aside Sophocles (c. 496-406 BC), inarguably the best known of the Athenian tragedians, in terms of the impact his works have had on the history of art and literature. The psychological depth he achieves in the seven of the 123 of his plays that have survived to the present day - most notably the three Theban plays: Antigone, Oedipus the King, and Oedipus at Colonus - not only inspired the Athenians, among whom Sophocles was honoured as a hero long after his death, but in our own time, have provoked landmark works on phychoanalysis and literary criticism, by thinkers like René Girard and, most famously, Sigmund Freud. In its masterful treatment of the marble this fragment sensitively captures the features of one of the most important playwrights of all time. Height on stand: 7.9 inches (20 cm). Provenance: Collection of Danish sculptor Jens Adolf Jerichau...Category

Antique 15th Century and Earlier Classical Roman Busts

MaterialsMarble

- Ancient Hellenistic Glass Finger RingLocated in London, GBThis beautifully preserved ring was cast from light green transparent glass. Its large size and shape are typical of Hellenistic finger rings, and its now ...Category

Antique 15th Century and Earlier Classical Greek Glass

MaterialsGlass

You May Also Like

- Set of Verdigris Bronze Hellenistic Sculptures, ItalyLocated in Pittsburgh, PASet of Beautifully Detailed Bronze Surrealist or Hellenistic Sculptures in the Style of Giacometti. Italy, circa 1930.Category

Vintage 1930s Italian Hellenistic Figurative Sculptures

MaterialsBronze

- Hellenistic Style Plaster BustLocated in Stockton, NJA Hellenistic style plaster bust. Solid and heavy construction.Category

20th Century European Hellenistic Busts

MaterialsPlaster

- 1990s Japanese Hannya Mask Noh Theatre Demon Devil Serpent Dragon Asian Wall ArtLocated in Hyattsville, MDVery old hand carved mask, exact age is unknown, signed. The Hannya mask represents jealous female demon, serpent and sometimes dragon in Noh and Kyogen J...Category

Early 20th Century Japanese Tribal Figurative Sculptures

MaterialsWood

- Large Carved Oak Grotesque CorbelLocated in Bradenton, FLLarge heavy 18th century or earlier carved oak corbel. The corbel depicts a large male open-eyed smiling face with broad features. Finly carved details with wonderful old patina.Category

Antique 18th Century European Gothic Figurative Sculptures

MaterialsOak

- Terra Cotta Gargoyle / Grotesque HeadLocated in Chicago, ILFantastic terra cotta gargoyle / grotesque head. Rare and unique.Category

Vintage 1920s American Architectural Elements

MaterialsTerracotta

- Early 20th Grotesque MascotLocated in Marseille, FREarly 20th grotesque mascot.Category

Early 20th Century French Figurative Sculptures

MaterialsBronze