Items Similar to Hungarian Rabbi Akiba Eger 19thC Judaica Folk Art Tapestry Needlepoint Sampler

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 8

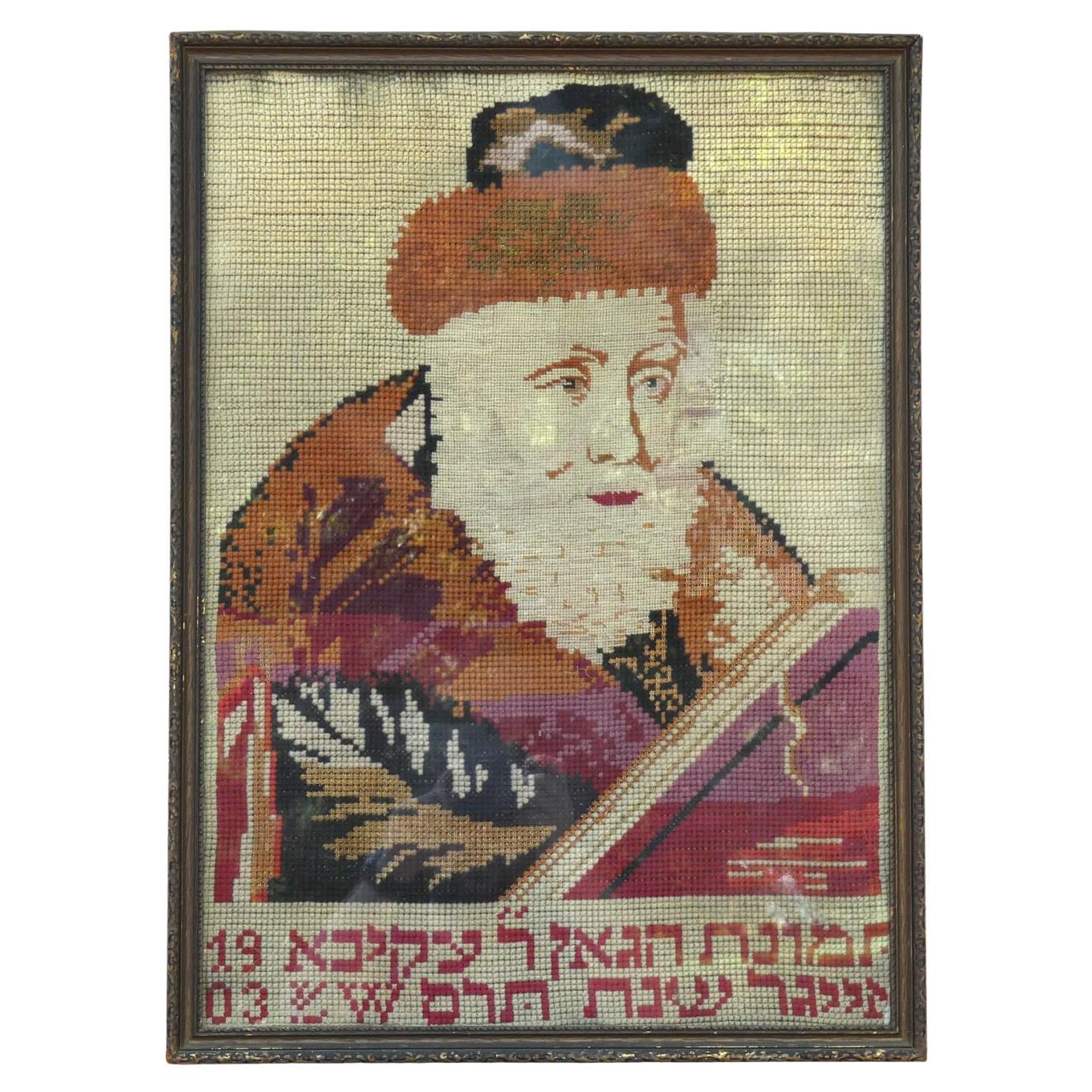

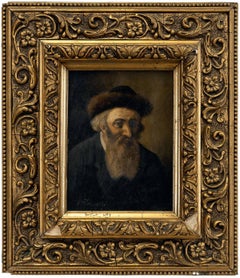

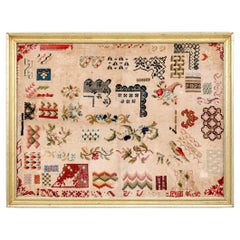

UnknownHungarian Rabbi Akiba Eger 19thC Judaica Folk Art Tapestry Needlepoint Sampler

$3,200

£2,430.92

€2,799.19

CA$4,577.92

A$5,021.54

CHF 2,589.42

MX$59,977.31

NOK 32,841.72

SEK 30,809.26

DKK 20,918.32

About the Item

Dimensions board backing is 2 X 18.5 board opening is 16.5 X 13 inches

19th Century framed tapestry of a Rabbi, embroidered sampler, with beaded script below. (it reads J. Eger Oberlandes Rabbiner or Oberlander Rabbiner) There is some sort of texture and dimension to his fur hat (Shtreimel) and coat collar. This is being sold without the frame..

Rabbi Akiba Eger (5521-5598; 1761-1838)

Rabbi Akiba Eger was one of the greatest scholars of his time, who had a great influence on Jewish life. He was born in Eisenstadt, Hungary, in the year 5521 (1761), nearly two hundred years ago. The city of his birth was a seat of learning for centuries, and his family was a family of scholars and Rabbis.Rabbi Akiba Eger, who was Rabbi in the famous community of Pressburg (also Hungary, but since 1913 it belonged to Czechoslovakia and was called Bratislava). He was invited to become Rabbi of the famous city of Posen, and in fact became the chief rabbi of the entire Posen province, though he did not carry that title. His famous son-in-law, Rabbi Moshe Sofer (known as the 'Chasam Sofer'), Rabbi of Pressburg, who had married Rabbi Akiba Eger's daughter. King Frederick III of Prussia honored him with a special medal. Rabbi Akiba Eger was recognized as a great authority on Jewish law, and many well known rabbis and Jewish leaders turned to him for advice and decisions on points of law.

"This sort of art, craft work, emerges from a long tradition of Jewish folk art.

Today, many of these artists are professionally trained and bring a fine arts sensibility to their Judaica work. This is a relatively new phenomenon. Only in the last few centuries have Jewish artists trained in the fine arts. For the greater part of Jewish history, most Judaica artists were untrained, and their art was not their life’s work, but was simply one form of devotion to God. Known today as “Jewish folk art,” the tradition of Jewish visual expression includes paper-cutting, creation of the mizrach and shivitti (two forms of decorative signs), and the art of micography (using words to create images). Looking with contemporary eyes at these primarily self-taught forms of expression offers inspiration and assurance that the visual arts hold a prominent place in Jewish civilization.

At first glance, any work of “folk art” may at first seem childish or naive; what makes it great art is that at second glance, the art reveals depth and substance. Jewish paper cutting was, for centuries, more or less of a hobby of a primarily male, religious population. These men, and women, included rabbis, yeshiva teachers, and students, people who had time to use their hands even as they focused on study and discussion.

Paper-cutting was an inexpensive art — no fancy materials were needed, just a scrap of paper, a pencil, a knife. At the same time, some artists used more expensive materials, such as parchment, resulting in paper-cut art better able to be preserved. The tradition of Jewish paper-cutting was borrowed by the Jews of the Middle Ages’ Christian and Muslim neighbors. It can be traced as far back as the 14th century, and it continued to play a major cultural role in Jewish tradition through the 19th and early 20th centuries.s

The craft takes a simple art–cutting paper to create a design (think of making a snowflake in grade school)–and transforms it into an expression of devotion. The artist would take a line of text, from Psalms, for instance, and would strive to bring the imagery of the text alive in the paper-cut.

As time went on, paper-cutting became more esteemed, and soon paper-cut designs became connected with certain lifecycle events and holidays. Artists used paper-cutting to illustrate ketubot (marriage contracts), for example, and would create certain designs for the Jewish festivals of Sukkot and Shavuot. While Jewish literary tradition focused on the importance of words, the folk art tradition brought visual representations of words and ideas to life.

Artists often used paper-cutting to create a mizrach (which literally means “east”). The mizrach was a wall hanging for the most eastern wall of the Jewish home, reminding them which way to face while praying–toward Jerusalem–and directing the family’s thoughts to that holy city during prayer. In Eastern Europe, the mizrach was frequently an object not just of devotion, but also of beauty. Elaborate mizrachim (plural of mizrach), created by paper-cutting techniques adorned many Jewish homes. Though the intention of the mizrach was to serve a simple, religious function, the art of the mizrach shows the high regard that was paid to good craftsmanship and beautiful aesthetic sense. Many mother and Jewish woman made a wimpel for their children's births. Another example of Jewish folk art, dating back to the Middle Ages, was the creation of the shiviti (meaning “awareness.”). Similar to the mizrach in that its function was to focus attention, the shivviti would hang in the synagogue. Inspired by a line from Psalms, “Shivitti Adonai Lanegdi Tamid”– I am ever aware of the Eternal One’s presence”–the shivviti employed the Hebrew letters “yud, hay, vav, hay” which together symbolize God’s name. It is interesting to note that while it was forbidden to try to utter the name of God, the shivviti used these letters in an artistic design to represent God’s presence. The shivviti might include other Biblical phrases or lines from Psalms, but the focus of its design was always the letters “yud, hay, vav, hay.” The shivviti, like the mizrach, was often created by paper-cutting, although examples of shivviti created by embroidery, drawing, and other media do exist. (Credit: My jewish Learning)

- Dimensions:Height: 22 in (55.88 cm)Width: 18.5 in (46.99 cm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:wear commensurate with age. with some minor toning, staining. needs new mounting. mat has wear.

- Gallery Location:Surfside, FL

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU38211835352

About the Seller

4.9

Platinum Seller

Premium sellers with a 4.7+ rating and 24-hour response times

Established in 1995

1stDibs seller since 2014

1,819 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 1 hour

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: Surfside, FL

- Return Policy

Authenticity Guarantee

In the unlikely event there’s an issue with an item’s authenticity, contact us within 1 year for a full refund. DetailsMoney-Back Guarantee

If your item is not as described, is damaged in transit, or does not arrive, contact us within 7 days for a full refund. Details24-Hour Cancellation

You have a 24-hour grace period in which to reconsider your purchase, with no questions asked.Vetted Professional Sellers

Our world-class sellers must adhere to strict standards for service and quality, maintaining the integrity of our listings.Price-Match Guarantee

If you find that a seller listed the same item for a lower price elsewhere, we’ll match it.Trusted Global Delivery

Our best-in-class carrier network provides specialized shipping options worldwide, including custom delivery.More From This Seller

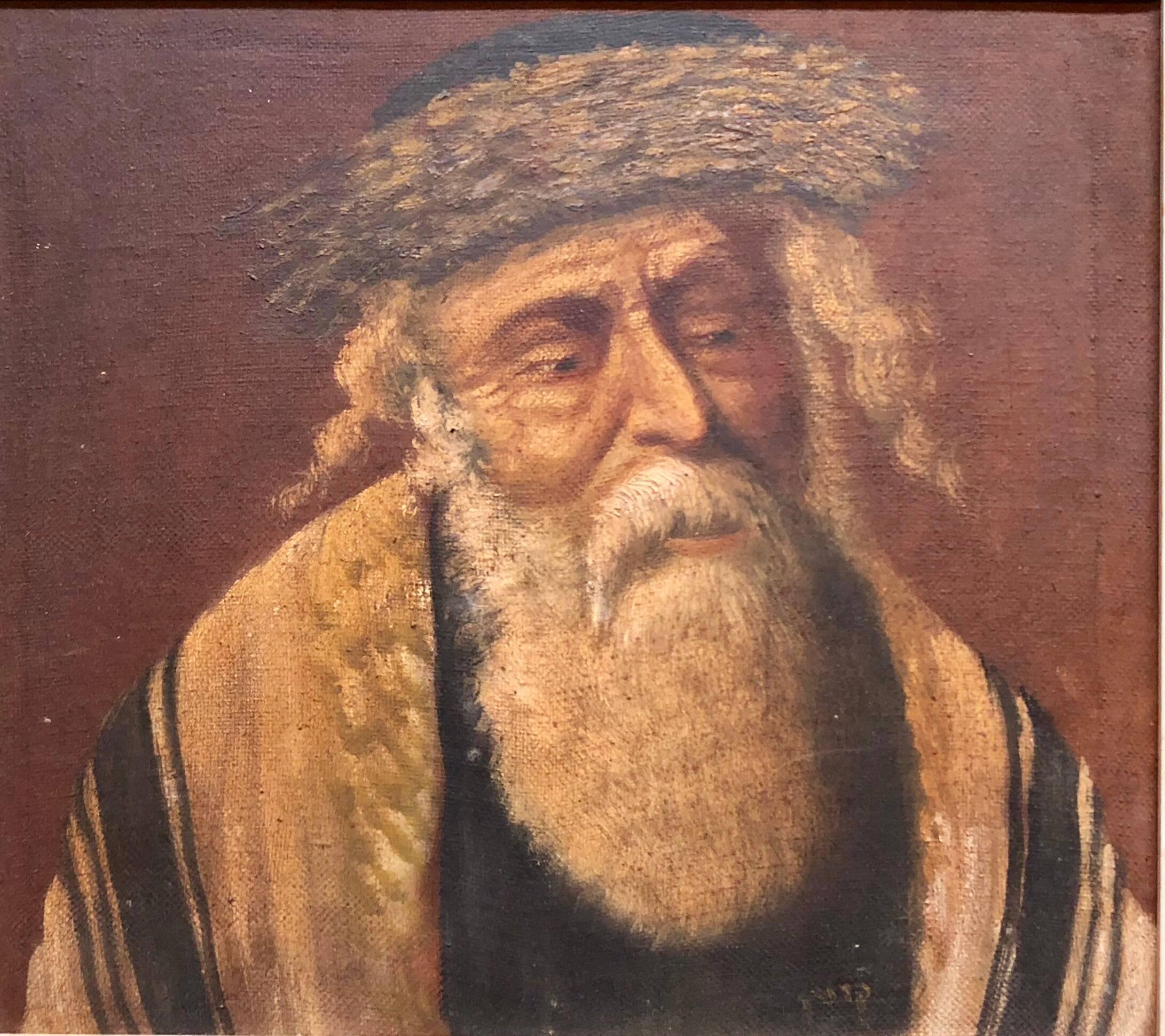

View AllChassidic Rabbi with Shtreimel, Rare Judaica Oil Painting Signed in Hebrew

Located in Surfside, FL

Rare Judaica Art. Jewish genre scene. In the tradition of Moritz Oppenheim, Isidor Kauffman and Maurycy Gottlieb and later of Tully Filmus, Zalman Kle...

Category

Mid-20th Century Post-Impressionist Figurative Paintings

Materials

Oil

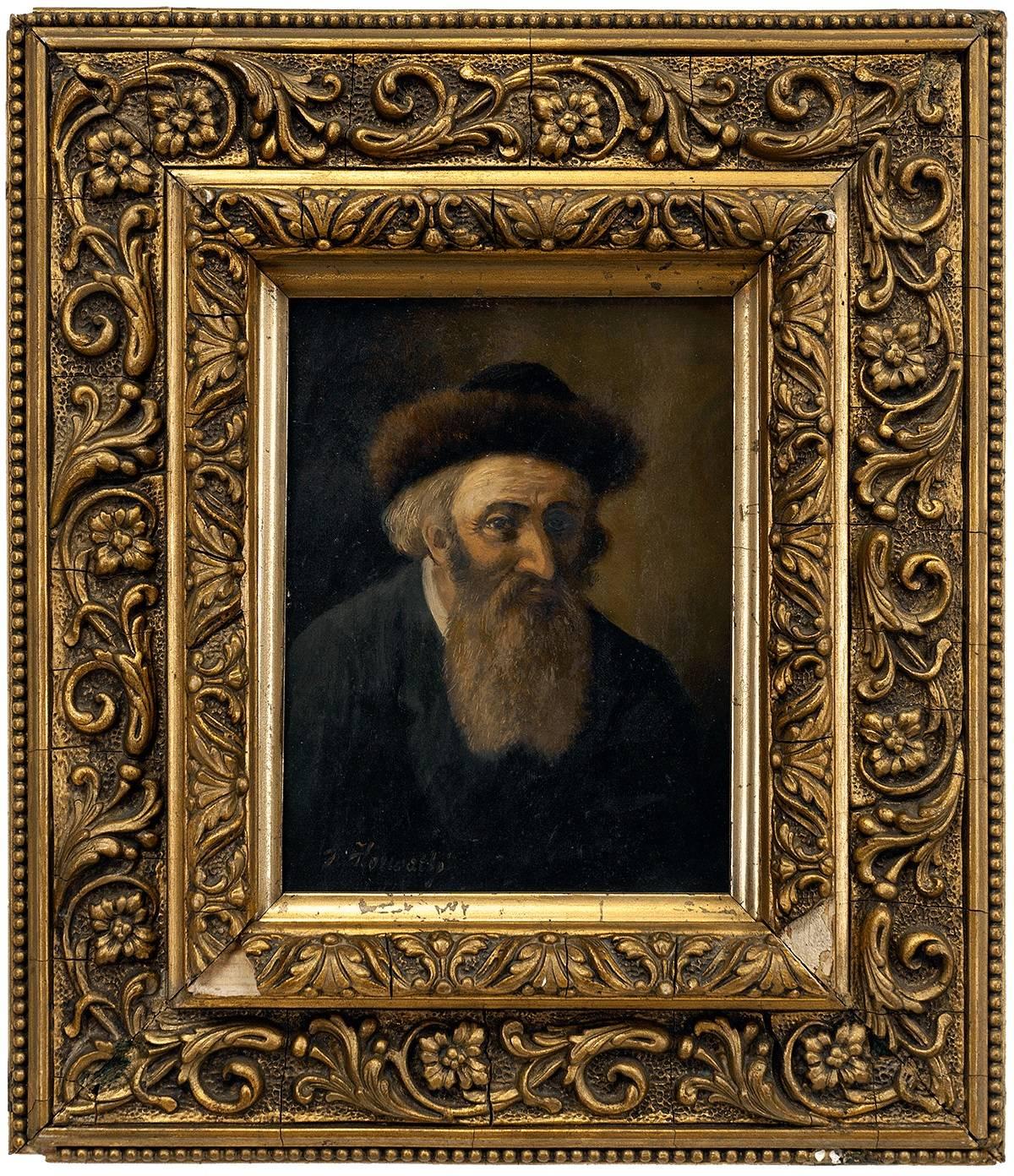

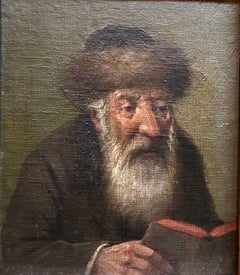

Rare Hungarian Judaica Hasidic Rabbi with Shtreimel Pre War Oil Painting

Located in Surfside, FL

14.25 X 12.5 with frame. 8.75 X 7.25 without frame

Category

20th Century Naturalistic Figurative Paintings

Materials

Canvas, Oil

Rare Modernist Judaica Scholar Rabbi in Synagogue Oil Painting Signed Mora

Located in Surfside, FL

a mid century Judaica painting of a Rabbi wearing a Tallit prayer shawl. In the Modernist manner of Maurice Kish, Tully filmus or William Gropper. ...

Category

20th Century Folk Art Portrait Paintings

Materials

Oil

Pre World War II Austrian Judaica Oil Painting Hasidic Rabbi Portrait

By Rudolf Klinsbogl Klingsberg

Located in Surfside, FL

Rudolf KLINGSBÖGL Austrian Viennese painter and teacher. Chassidic rebbe with Shtreimel.

Klingsbogl was active in Vienna and is known for his typical portraits and paintings of interiors - workshops, pubs and cellars. His style is very distinctive. rare to find good jewish work that survived the holocaust as so much of it was destroyed.

Other works by Rudolf Klingsbogl (sometimes known as Klingsberg}: Rabbis Studying Around a Table, The Huntsman, The Pet Bird, Blacksmith Interior Scene, Three Men with Chat and Drink, The Sailors, The Old Drinker, Debating the News, Sunday Afternoon, Man Looking at Pocket Watch. Game of Cards in a Tavern, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart as a Child, Franz Schubert at the Piano, Johann Strauss (The Younger).

Realistic portrait of an older rabbi visiting and blessing a child in a European marketplace...

Category

Early 20th Century Academic Portrait Paintings

Materials

Oil

Wool Felt Craft Applique Vintage Israeli Judaica Folk Art Tapestry Kopel Gurwin

By Kopel Gurwin

Located in Surfside, FL

This depicts King David playing the harp, along with a verse in Hebrew from the Psalms. all made by hand. woven and stitched. Vintage, original piece.

Kopel Gurwin (Hebrew: קופל גור...

Category

20th Century Folk Art Mixed Media

Materials

Wool, Felt

Rare Modernist Hungarian Rabbi Pastel Drawing Gouache Painting Judaica Art Deco

By Hugó Scheiber

Located in Surfside, FL

Rabbi in the synagogue at prayer wearing tallit and tefillin.

Hugó Scheiber (born 29 September 1873 in Budapest – died there 7 March 1950) was a Hungarian modernist painter.

Hugo Scheiber was brought from Budapest to Vienna at the age of eight where his father worked as a sign painter for the Prater Theater. At fifteen, he returned with his family to Budapest and began working during the day to help support them and attending painting classes at the School of Design in the evening, where Henrik Papp was one of his teachers. He completed his studies in 1900. His work was at first in a post-Impressionistic style but from 1910 onward showed his increasing interest in German Expressionism and Futurism. This made it of little interest to the conservative Hungarian art establishment.

However, in 1915 he met the great Italian avant-gardist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and the two painters became close friends. Marinetti invited him to join the Futurist Movement. The uniquely modernist style that he developed was, however, closer to German Expressionism than to Futurism and eventually drifted toward an international art deco manner similar to Erté's. In 1919, he and his friend Béla Kádar held an exhibition at the Hevesy Salon in Vienna. It was a great success and at last caused the Budapest Art Museum to acquire some of Scheiber's drawings. Encouraged, Scheiber came back to live in Vienna in 1920.

A turning point in Scheiber's career came a year later, when Herwarth Walden, founder of Germany's leading avant-garde periodical, Der Sturm, and of the Sturm Gallery in Berlin, became interested in Scheiber's work. Scheiber moved to Berlin in 1922, and his paintings soon appeared regularly in Walden's magazine and elsewhere. Exhibitions of his work followed in London, Rome, La Paz, and New York.

Scheiber's move to Germany coincided with a significant exodus of Hungarian artists to Berlin, including Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Sandor Bortnyik. There had been a major split in ideology among the Hungarian avant-garde. The Constructivist and leader of the Hungarian avantgarde, Lajos Kassák (painted by Hugó Scheiber in 1930) believed that art should relate to all the needs of contemporary humankind. Thus he refused to compromise the purity of his style to reflect the demands of either the ruling class or socialists and communists. The other camp believed that an artist should be a figurehead for social and political change.

The fall out and factions that resulted from this politicisation resulted in most of the Hungarian avant gardists leaving Vienna for Berlin. Hungarian émigrés made up one of the largest minority groups in the German capital and the influx of their painters had a significant effect on Hungarian and international art. Another turning point of Scheiber's career came in 1926, with the New York exhibition of the Société Anonyme, organized by Katherine Dreier. Scheiber and other important avant garde artists from more than twenty-three countries were represented. In 1933, Scheiber was invited by Marinetti to participate in the great meeting of the Futurists held in Rome in late April 1933, Mostra Nazionale d’Arte Futurista where he was received with great enthusiasm. Gradually, the Hungarian artists began to return home, particularly with the rise of Nazism in Germany. Kádar went back from Berlin in about 1932 and Scheiber followed in 1934.

He was then at the peak of his powers and had a special flair in depicting café and cabaret life in vivid colors, sturdily abstracted forms and spontaneous brush strokes. Scheiber depicted cosmopolitan modern life using stylized shapes and expressive colors. His preferred subjects were cabaret and street scenes, jazz musicians, flappers, and a series of self-portraits (usually with a cigar). his principal media being gouache and oil. He was a member of the prestigious New Society of Artists (KUT—Képzőművészek Új Társasága)and seems to have weathered Hungary's post–World War II transition to state-communism without difficulty. He continued to be well regarded, eventually even receiving the posthumous honor of having one of his images used for a Russian Soviet postage stamp (see image above). Hugó Scheiber died in Budapest in 1950.

Paintings by Hugó Scheiber form part of permanent museum collections in Budapest (Hungarian National Museum), Pecs (Jannus Pannonius Museum), Vienna, New York, Bern and elsewhere. His work has also been shown in many important exhibitions, including:

"The Nell Walden Collection," Kunsthaus Zürich (1945)

"Collection of the Société Anonyme," Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut (1950)

"Hugó Scheiber: A Commemorative Exhibition," Hungarian National Museum, Budapest (1964)

"Ungarische Avantgarde," Galleria del Levante, Munich (1971)

"Paris-Berlin 1900-1930," Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (1978)

"L’Art en Hongrie, 1905-1920," Musée d’Art et l’Industrie, Saint-Etienne (1980)

"Ungarische Avantgarde in der Weimarer Republik," Marburg (1986)

"Modernizmus," Eresz & Maklary Gallery, Budapest (2006)

"Hugó Scheiber & Béla Kádár," Galerie le Minotaure, Paris and Tel Aviv (2007)

Hugó Scheiber's paintings continue to be regularly sold at Sotheby's, Christie's, Gillen's Arts (London), Papillon Gallery (Los Angeles) and other auction houses.

He was included in the exhibition The Art Of Modern Hungary 1931 and other exhibitions along with Vilmos Novak Aba, Count Julius Batthyany, Pal Bor, Bela Buky, Denes Csanky, Istvan Csok, Bela Czobel, Peter Di Gabor, Bela Ivanyi Grunwald, Baron Ferenc Hatvany, Lipot Herman, Odon Marffy, C. Pal Molnar...

Category

Early 20th Century Modern Figurative Paintings

Materials

Paper, Charcoal, Pastel, Watercolor, Gouache

You May Also Like

Needlepoint Artwork Portrait of R' Akiva Eger 1900/1903, Judaica

Located in New York, NY

A unique and beautifully preserved needlepoint textile portrait of Rabbi Akiva Eger (1761–1837), one of the most revered Talmudic scholars of the 18th–19th century. This hand-stitche...

Category

Antique Early 1900s European Paintings

Materials

String

19th Century Needlepoint Tallit Bag, Jerualem

Located in New York, NY

An Intricate Jerusalem Textile, made in Jerusalem, 1886.

Double-sided large pouch. Wool thread embroidered on cotton net. One side has a lion and stag holding flags reading “Jerusalem” in Hebrew, which flank a crowned Ten Commandments. Titled in Hebrew “Swift as a deer, strong as a lion” (Ethics of the Fathers 5:20). “Jerusalem” is seen in large lettering, atop a pair of birds and flowers. Top scene of the reverse side is titled “Mount of Olives”, amongst a plethora of olive trees, and a cluster of buildings is titled “Chulda the Prophetess”, (where her and others tombs reside). Main scene is titled “The Western Wall”, which features the wall and outer structures with turrets and Cyprus trees. The Hebrew date of “1886” is revealed on the bottom corners. This delicate textile, incredibly vibrant in color after 130 years of being created, is a masterful, exceedingly rare work of art produced in Jerusalem by an unknown woman --- likely quite young, a teenager --- as a gift to an unknown individual. Too complex to be a “tourist trinket”, as we know of one other similarly-made textile that is in the collection of the Israel Museum, and is dated 1876: see the book “Jewish Folk Art: From Biblical Days to Modern Times”, page 122. A clue to where perhaps this was made is in the depiction of the lion and stag holding flags, as they are identical to those featured on the crest of Moses Montefiore. In the 19th century, Montefiore gave enormous sums of money to purchase land for Jewish settlements and establish schools in Palestine. This textile most likely hailed from a school for girls funded by Montefiore, and was made as either a gift for Montefiore himself, or another wealthy donor. As to the actual purpose of this textile, since it is in the form of a large pouch, its intended purpose might have been to hold a tallit (prayer...

Category

Antique 1880s Israeli Religious Items

Materials

Textile

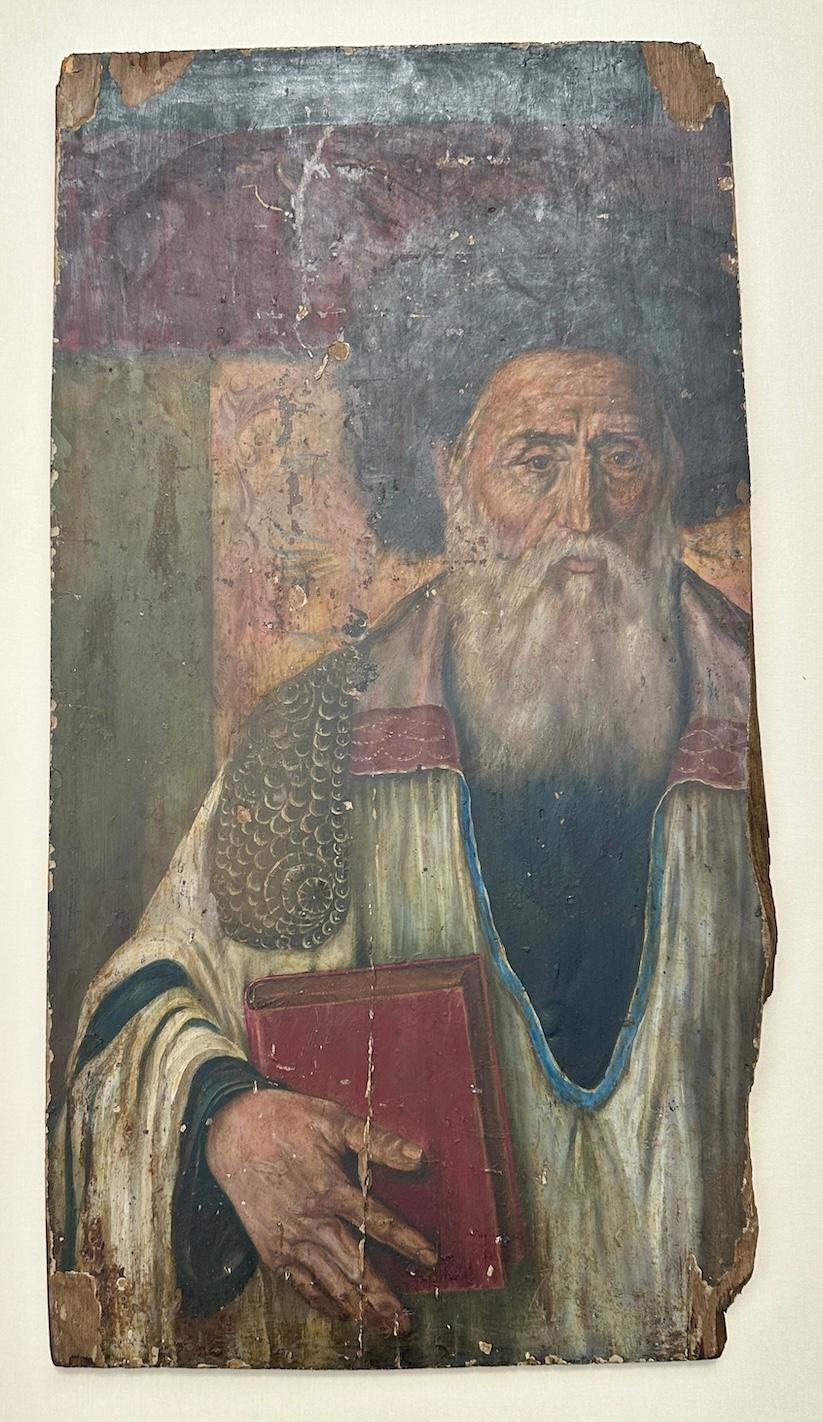

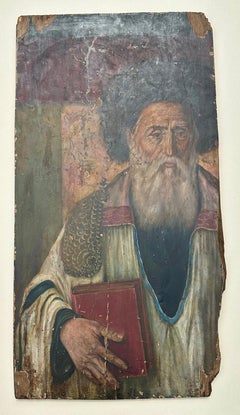

19th century Oil portrait of a Hungarian Rabbi

Located in Woodbury, CT

This 19th-century oil on panel portrait depicts a Hungarian Rabbi, characterized by his traditional attire and solemn expression. The Rabbi is portrayed with a long, white beard and ...

Category

1890s Old Masters Figurative Paintings

Materials

Oil, Wood Panel

Antique Berlin Wool-work Needlepoint Sampler

Located in Bridgeport, CT

An antique needlepoint sampler depicting samples of lace patterns, florals, bird and geometric motifs.

Presented in a metallic gold frame ...

Category

Antique 19th Century Country Tapestries

Materials

Fabric, Wool

American Needlework Sampler by Eliza Jordan, Aged 12, Late 18th Century

Located in Nantucket, MA

Antique American needlework sampler by Eliza Jordan, aged 12, late 18th century, a very fine and fanciful pictorial needlework sampler on l...

Category

Antique Late 18th Century American Folk Art Tapestries

Materials

Linen

COLLECTABLE ANTIQUE ANTIQUE 1791 GEORGE III NEEDLEWORK SAMPLER ORiGINAL STAMPED

Located in West Sussex, Pulborough

Royal House Antiques

Royal House Antiques is delighted to offer for sale this rather stunning, 1791 dated needlework sampler from Scotland

I have a number of these samplers for sal...

Category

Antique 1790s English Regency Tapestries

Materials

Cotton