Items Similar to Sunny beach scene with beach houses in Trouville-sur-mer (France)

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 8

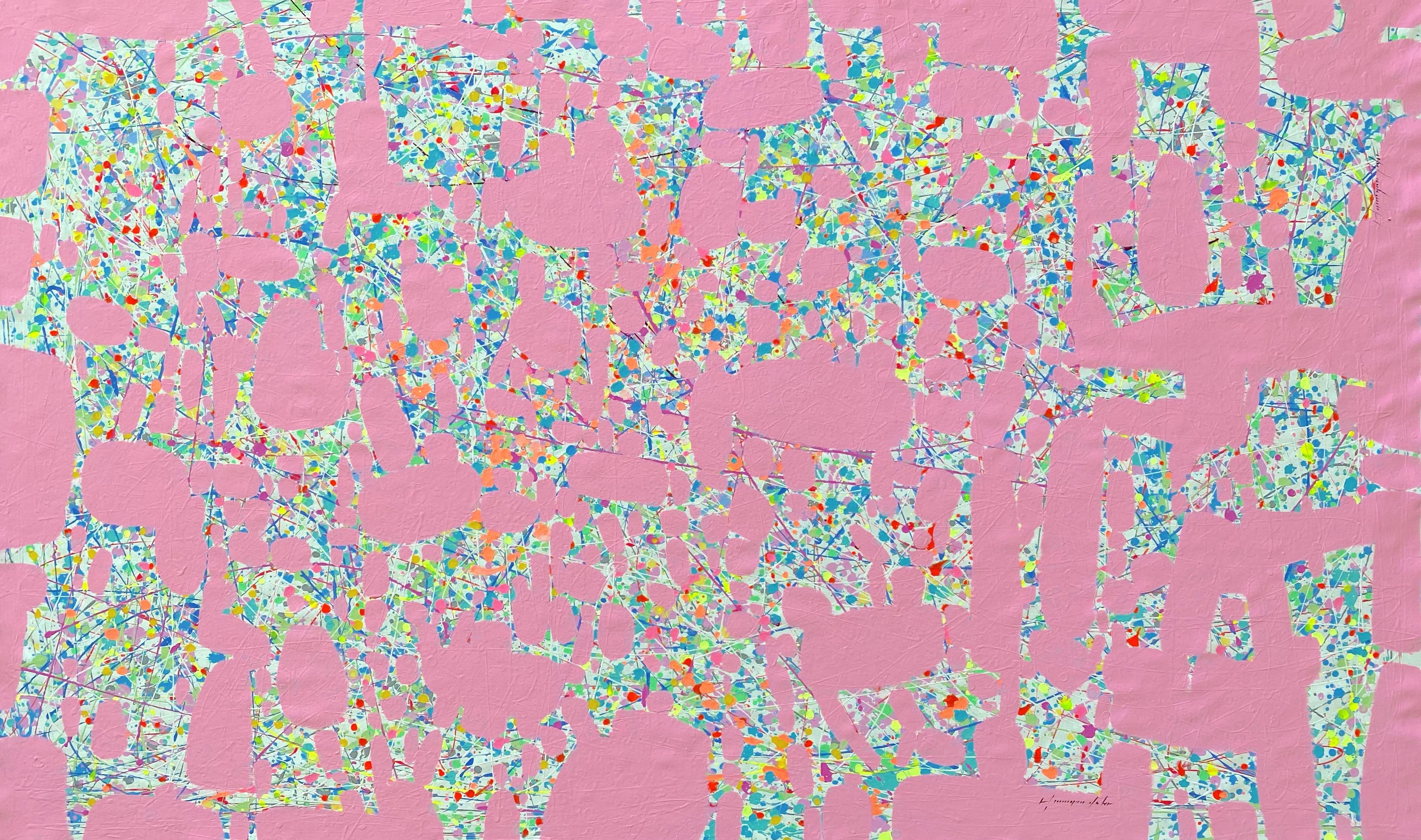

Sander van WalsumSunny beach scene with beach houses in Trouville-sur-mer (France)2023

2023

About the Item

As a boy, journalist and artist Sander van Walsum was captivated by Monet. That love did not fit into the spirit of the times at the time, but his fascination has never disappeared. That is why he goes with acrylic paint and a tear palette to the locations where his idol painted to find the answer to the question: what makes the impressionist so brilliant?

It would have been March 1973, so more than fifty years ago. At De Slegte on the Oudegracht in Utrecht, I, a resident of neighboring Doorn, opened a German-language book with paintings by Claude Monet (1840-1926). It could also have been a book about Cézanne or Van Gogh. Or, if the history department was located closer to the entrance, a book about the Second World War. But it was the richly illustrated book about Monet that really impressed me.

My interest was immediately aroused by a still life with garlic cloves and a hunk of beef ('Ochsenslende') from 1864. Then by a 'Blühender Garten' and a terrace in the French coastal town of Sainte-Adresse, lined with brightly colored flowers. But the superlative of beauty – to my untrained eyes – was reached on page 25. There was printed a reproduction of Hôtel des Roches Noires at Trouville, a painting Monet had made in July 1870. I looked at it with admiration, almost disbelief. the precise brushstrokes with which Monet had characterized the opulence of the building and the grace of the flâneurs on the half-shaded terrace. But above all, I was struck by the bravado with which Monet painted the large (American?) flag in the foreground, crackling in the onshore wind. The fairytale effect was achieved by red and off-white strokes that Monet must have applied to an unpainted part of the canvas in a few passionate seconds.

Sander van Walsum is a reporter and commentator for de Volkskrant. He also reviews non-fiction. Previously, Van Walsum was a correspondent in Berlin.

After purchasing the book, I rushed to 'American lunchroom' Van Angeren on Lange Viestraat to take a closer look at Monet's world. I saw recreationists on the banks of the Seine, sailing boats in Argenteuil, bathers in Trouville, still lifes, ladies with parasols, rolling fields of poppies, Amsterdam cityscapes, trains belching steam, the cathedral of Rouen in full sun and at sunset, twilight in Venice , the smog of London and the lilies in Monet's garden in Giverny. But I kept returning to page 25, to Hôtel des Roches Noires.

The painting aroused in me a strong longing for a time that – I thought – was so much more beautiful than ours. Only years later, when I too had become interested in history, did I realize that Monet must have captured the glory of the bathing season in Trouville when the Franco-Prussian War was about to break out - or had already begun. There must have been a depressed mood in the salon and on the terrace of the Hôtel des Roches Noires during the bathing season of 1870.

Monet escaped the war by fleeing to England. For him, this had the additional advantage that he also shook off the French creditors from whom he had until then escaped by moving regularly. But from an art historical perspective, Monet's flight is important for two other reasons: in England he became acquainted with the oeuvre of the romantic landscape painter William Turner (by whom he was strongly influenced), and he himself was discovered by art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel , which introduced Monet and other practitioners of the loose touch to the art-loving public. In 1873, exactly 150 years ago, Monet united the avant-gardists of that moment in the Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs et engravers. A year later, the members, who were soon called 'Impressionists', organized their first group exhibition.

I wanted to become proficient in painting at the drawing teacher training course in Utrecht. Not with the intention of becoming a teacher, but to bridge the time until my discovery by a wealthy art connoisseur. However, I had ignored the spirit of the times. My first painted landscape was still tolerated. The second was thoroughly abstracted by a teacher. But the third was unceremoniously pulled from the donkey. After all, figurative art was hopelessly outdated ('Didn't you know that yet?') and Monet had been demoted to a cookie-cutter and calendar painter by the then avant-garde (which also included my art teachers).

Not only would Monet's 'visual language' have fallen into disuse, he would also have shown a complete lack of social commitment by painting 'beautifully' at a time that was really very ugly for most of his contemporaries. I kept quiet about the fact that for me this was precisely the great attraction of Impressionism. Because I was overloaded with social commitment during those years. If I didn't find the report of the Club of Rome on the coffee table in my parental home, there was a writing by Joke Smit or a kindred feminist by whom my mother had become noticeably captivated.

During class evenings, the themes of the day were discussed, sometimes with raised voices – which partly determined the composition of your circle of friends: the colonel's regime in Greece, the 'fascist' regimes in Spain and Portugal, the decolonization of Angola and Mozambique, the war in Vietnam, the recognition of the GDR and the decency of refusing military service. Even the traditional dew-trapping, on the early morning of Ascension Day, was not without these kinds of topics for discussion.

The light-hearted oeuvre of the Impressionists was therefore a pleasant change from the heavy food that was presented to me every day. And the lack of an intrusive commitment still attracts me to their oeuvre – in that sense I have not undergone any significant development as an art lover and practitioner since 1973. I appreciate paintings mainly because of their beauty (definable or otherwise), not because of any message. Books, films and photos are much more suitable vehicles for this.

When I see paintings that draw attention to current themes, I feel like Karel van het Reve when he saw Picasso's Guernica for the first time: he tried 'with all his might to find it beautiful' but failed. 'Beautiful' paintings are considered so suspicious that a few years ago the Rijksmuseum had an exhibition of beautiful, standing portraits flanked by an exhibition about decadence, as a disclaimer: the sin that many of the subjects apparently had in common.

My teachers at the Utrecht teacher training college could have thought of it. I became so discouraged by their dogmas that I decided to study history. After my studies I ended up in journalism, and it was only ten years ago that I started painting regularly again - unhindered by the need for proof or the fashions of the day. To conclude a career of 38 years in journalism, I was able to visit a number of places in France for this newspaper that can be associated with Monet - with the intention of painting there myself.

In Argenteuil I searched in vain for picturesque views. When Monet lived and worked there (from 1871 to '78), it was a lovely place where industrialization had slowly made its debut. Now it is a gray suburb of Paris where, with some difficulty, I found the bridge over the Seine, which was also immortalized by Monet. Fortunately, Vétheuil, a few kilometers downstream, is still in the same condition as it was in Monet's time. But in Monet's garden at Giverny I was part of a shuffling crowd of day trippers. Trouville-sur-Mer, on the other hand, still exudes the charm of Monet's beach scenes. Hôtel des Roches Noires, the final destination of my pilgrimage, is no longer a hotel but a somewhat shabby apartment complex, but this did not detract from the (art historical) sensation it evoked in me.

At the edge of the terrace, where Monet must have stationed himself on a beautiful day in July 1870, I prepared for a painting session en plein air – in the open air. Monet made school with this. Although he was not the first painter to work outside the studio – Eugène Boudin, Johan Barthold Jongkind and the so-called 'little masters' of the Barbizon School had preceded him – but for Monet light was more than an element in a landscape: it formed the soul of it. Under the influence of light, shapes became hard or soft, and landscapes or cityscapes underwent constant atmospheric changes. Even in shadows the light continues to work. That is why Monet rarely used black - to the incomprehension, even hilarity, of contemporaries who were conditioned by the dark genre paintings of the early 19th century.

There I was, on a sunny May day, around eleven o'clock in the morning, on the spot where my idol, in just a few hours, created the painting that figures on my mouse pad, in at least four of my art books and on a poster that has adorned one of the walls of my bedroom for many years. I had hoped to be able to work there under the same lighting conditions as Monet did 153 years ago. But for him the sun was higher – one of the wings of the hotel was already illuminated by it. I probably wouldn't have been able to capture that effect until a few hours later.

So I just made do with the circumstances as they presented themselves. And these conditions were not optimal. There was a strong wind that constantly threatened to take hold of the canvas and the tear palette on which I had applied some dabs of paint (also a blob of black) – acrylic paint, because it dries faster than oil paint. In the seclusion of the studio, this is an advantage for fans of the quick test. But in the sunny and windy spot where I sat, the paint was already subject to solidification before I had even started. I hadn't counted on that. Nor does it concern the fact that I have to rely on glasses for clear vision in the distance, while they actually hinder my view of the nearby canvas. As far as I know, Monet did not suffer from this (although later in life he did suffer from an eye problem that made him fear blindness).

I sketched the contours of the building towering above me and painted a few surfaces, each with its own basic color: a blend of Naples yellow, titanium white, burnt siena and a spoonful of raw umber for the facade of the hotel and the built environment in the background. A few strokes of green marking the hedges that have been planted in a strange spot in front of the building. A beige-like substance with a little Windsor violet for the terrace, and a mixture of ultramarine, brilliant blue, Windsor blue and titanium white for the sky.

Usually those first actions on a canvas are the most pleasant. You are still open-minded (the most optimal state of being in which the painter could be, according to Monet), the fear that a painting could fail does not yet arise and you do not yet lose yourself in excessive detail. Details – windows, fences and roof tiles – may tempt lovers of figurative art with the ultimate compliment 'that it looks real', but they actually mark the path of least resistance: those who dare to leave nothing out draw or paint everything. . But Monet usually managed to show all dimensions of a scene with a limited number of actions. In the case of Hôtel des Roches Noires: the reflection of the bright sunlight in the shade, the 'unfinished' flag that lacks nothing, the architectural complexity of the building. He knew when to stop; when the painting – according to his critical contemporaries no more than a rough sketch – was completed.

I was looking anxiously at the balconies, columns and other finery when the caretaker of the apartment complex appeared in my field of vision to announce that I was on private property and therefore had to end my work. In my best French I pointed out my artistic duty, knowing that this sounded far too bombastic to have any effect. Actually, I had no problems completing the canvas later in my office/studio based on photos. Because if painting en plein air does not encounter any practical problems or unforeseen weather conditions, the fun is undermined by passers-by who whisper their views on art behind your back (and usually have a lot of time to do so).

I consoled myself with the thought that Monet would also have used photos if he had already had a mobile phone with a camera. And with the idea that painting involves more than recording an impression - in any place and with any tools. Painting starts as soon as you walk through the city or through a forest and ask yourself: what makes this landscape this landscape? Which elements determine its character? What would I leave out and what would I accentuate? What colors would I use for the shadow? And which one for that building in the distance? How can I make the pleasure of painting visible on the canvas?

In doing so, I mainly mirror the 'early Monet', that of the 1970s and 1980s. In his younger years he was still guided by chance in his theme choices (although he once managed to persuade the station master of Gare Saint-Lazare in Paris to adjust the timetable to achieve the desired combination of steam and sunlight). But later he tried to freeze – even manipulate – fleeting moments. An oak tree was stripped of its leaves when Monet wanted to paint a bare tree. Farmers who wanted to feed their haystacks to the cows or cut down their poplar trees – popular motifs in Monet's oeuvre – refrained from doing so in return for a generous compensation.

Finally, Monet withdrew to a domain where he himself was lord and master: his garden in Giverny, where he settled in 1890. There he focused on painting plants, trees and - in particular - water lilies, which were trained by six gardeners (Monet was now very wealthy). And there he seems to have become entangled in his attempts to bend nature to his will. He started painting more hesitantly, and no longer satisfied himself with quick impressions: he often spent months tinkering with several canvases at the same time - in one of his studios, that too. While the white painted background still contributes to the clarity of his early works, in later works it has disappeared under thick layers of oil paint. The older Monet seemed to have lost the ability to say, after a few enthusiastic hours behind the easel: that's how it is done. Or if necessary: I'll leave it at this.

It is the tragedy of a painter who retained his enthusiasm, but who found it increasingly difficult to express it. Seen in this way, he has survived Impressionism. And Monet is not the only artist who only worked at the peak of his abilities for about twenty years. As a late bloomer (I dare to attribute that qualification to myself), I can also draw hope from this: if I had started painting in earnest fifty years ago, I would have finished blooming by now.

- Creator:Sander van Walsum (1957, Dutch)

- Creation Year:2023

- Dimensions:Height: 19.69 in (50 cm)Width: 23.63 in (60 cm)

- More Editions & Sizes:unique piecePrice: $1,527

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:ZEIST, NL

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU2614213538352

About the Seller

No Reviews Yet

Vetted Seller

These experienced sellers undergo a comprehensive evaluation by our team of in-house experts.

Established in 1999

1stDibs seller since 2023

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Ships From: ZEIST, Netherlands

- Return PolicyA return for this item may be initiated within 3 days of delivery.

More From This SellerView All

- Portrait of a Balinese beauty by Theo Meier (1908-1982)By Theo MeierLocated in ZEIST, UTAfter his academy Theo Meier moved to Germany where he came into contact with Max Liebermann and German expressionists from Die Brücke. Inspired by Paul Gauguin, he left for Tahiti at the age of 24. The influence of Paul Gauguin and the German Expressionists can be clearly seen in his works. After a year in Tahiti, he moved toBali where he found the culture and art that he had missed in Tahiti. He settled in Sanur and befriended the other artists who had settled in Bali, such as Rudolf Bonnet, Walter Spies, Antonio Blanco...Category

1940s Expressionist Figurative Paintings

MaterialsOil

- knotted tapestry by 'De Stijl' artist Bart van der Leck (1876-1958)Located in ZEIST, UTknotted tapestry by 'De Stijl' artist Bart van der Leck (1876-1958) with important provenance Bart van der Leck, together with Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, is one of the founding members of the 'De Stijl' group in 1916-1917. At that time, Bart van der Leck's work had a major influence on the development of the work of Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. This carpet comes from and is used in the Villa Schöne-van der Leck in Blaricum. The villa Schöne-van der Leck was built in 1953 after a design by Piet J. Elling in collaboration with the artist Bart van der Leck. The clients, Mr. and Mrs. O. Schöne-Van der Leck, were Bart van der Leck's son-in-law and daughter, respectively. The villa Schöne-van der Leck has exceptional art-historical value because of the collaboration between the architect Elling and 'De Stijl' artist Bart van der Leck, resulting in a total work of art according to the principles of 'De Stijl', in which the various disciplines have equal value. contributed. The property has a rarity value due to the fact that very few such total works of art have been preserved according to the principles of 'De Stijl'; as far as we know, this is the only one by Elling and Van der Leck. The entire house was decorated in 'De Stijl' visual language. Bart van der Leck made interventions in various rooms by applying color areas on walls and ceilings in the 'De Stijl' colors red, yellow and blue...Category

20th Century De Stijl More Art

MaterialsTapestry

You May Also Like

- French Contemporary Art by Jean Duquoc - Village près de l’OcéanBy Jean DuquocLocated in Paris, IDFAcrylic on canvas Jean Duquoc is a French artist born in 1937 who lives & works in Belz, Brittany in France. In his work, we can see the skill with which he uses color, moving direc...Category

2010s Impressionist Landscape Paintings

MaterialsAcrylic, Canvas

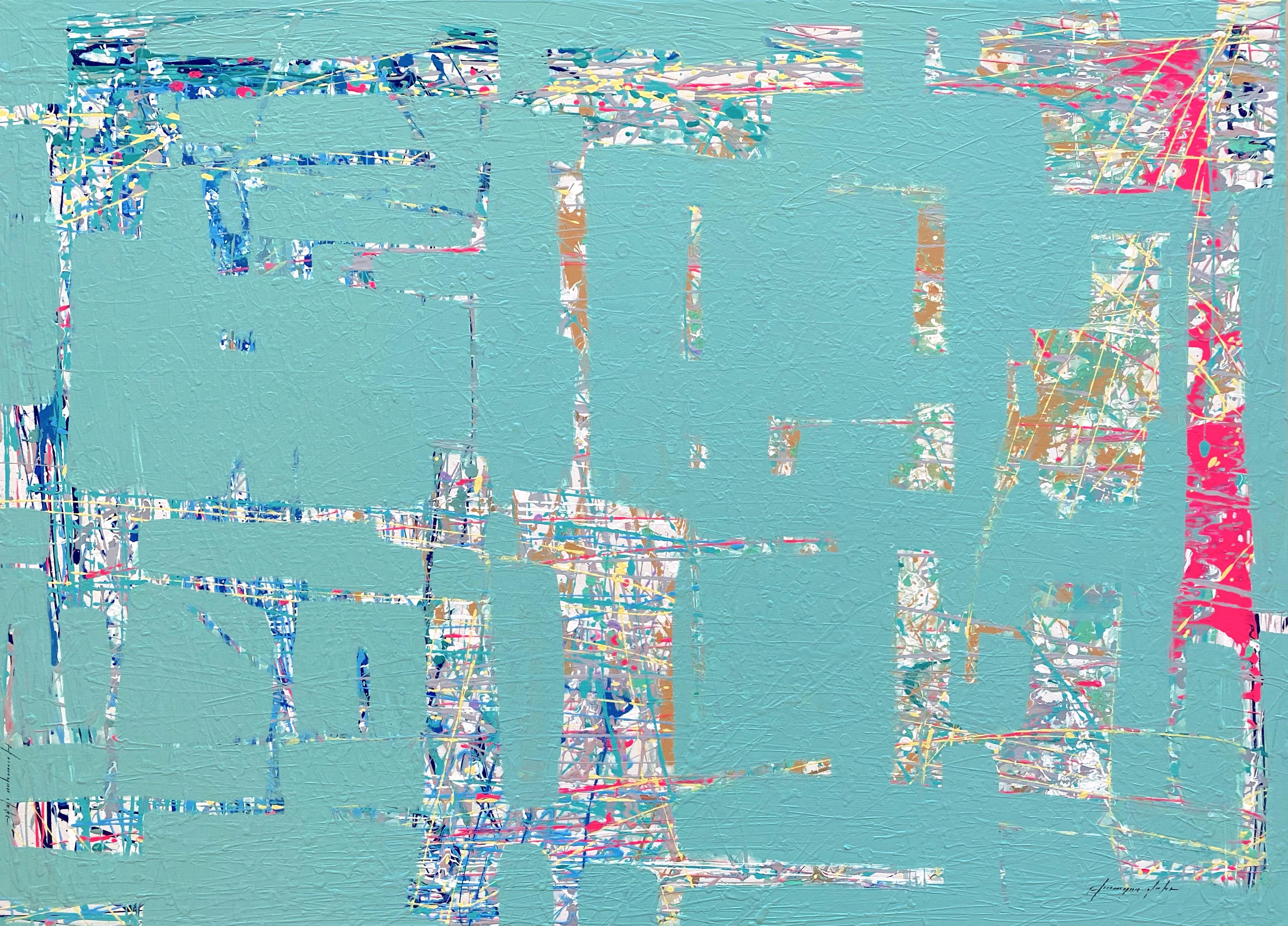

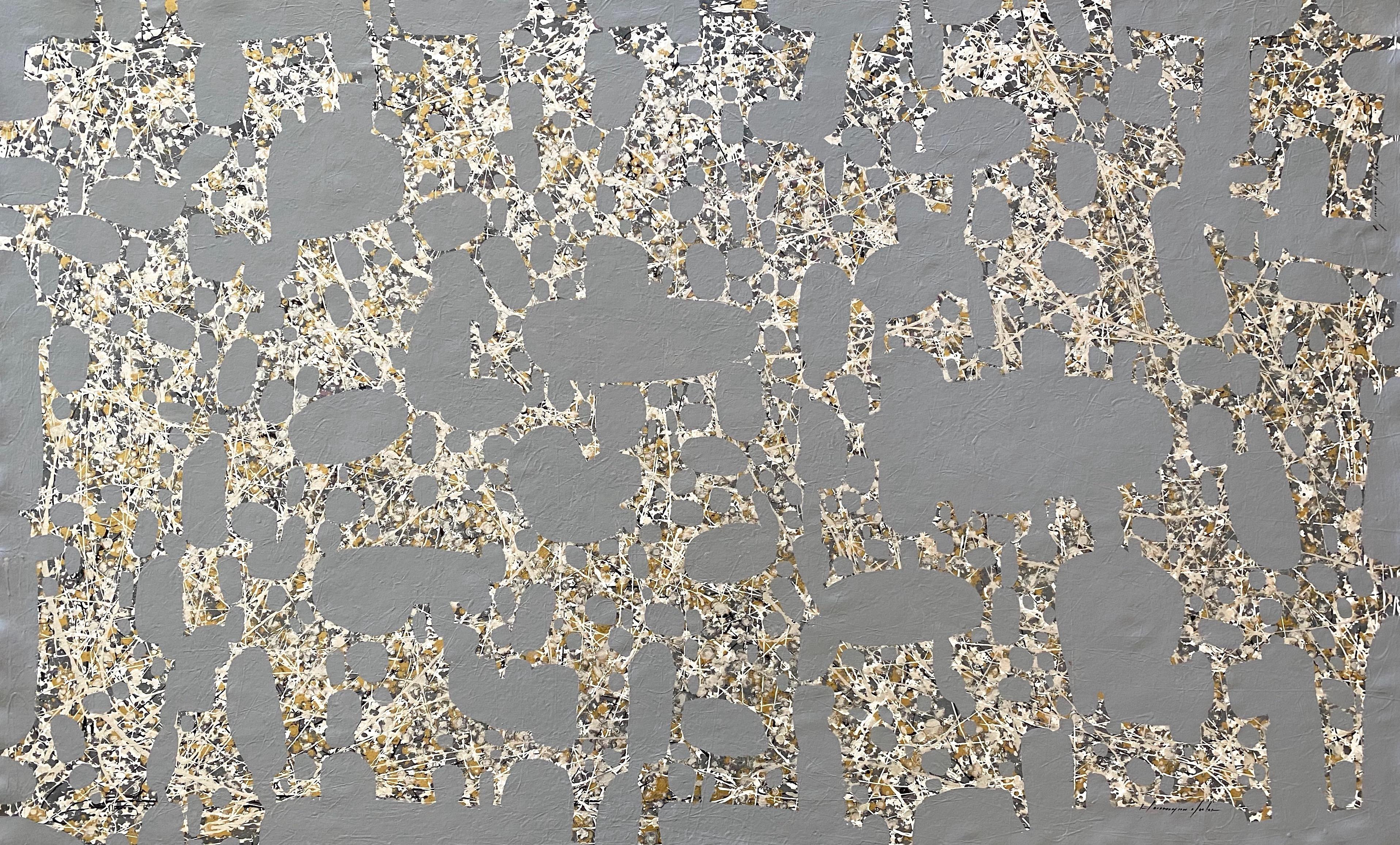

- Event Day, Abstract Original Painting, Ready to HangBy Vahe YeremyanLocated in Granada Hills, CAArtist: Vahe Yeremyan Work: Original Painting, Handmade Artwork, One of a Kind Medium: Acrylic on Canvas Year: 2022 Style: Abstract Art, Subject: Event Day, Size: 40" x 67" x 1''...Category

2010s Impressionist Landscape Paintings

MaterialsCanvas, Acrylic

- Sign of Transfer, Abstract Original Painting, Ready to HangBy Vahe YeremyanLocated in Granada Hills, CAArtist: Vahe Yeremyan Work: Original Painting, Handmade Artwork, One of a Kind Medium: Acrylic on Canvas Year: 2022 Style: Abstract Art, Subject: Sign of Transfer, Size: 40" x 55...Category

2010s Impressionist Landscape Paintings

MaterialsAcrylic, Canvas

- Century Wall, Abstract Original Painting, Ready to HangBy Vahe YeremyanLocated in Granada Hills, CAArtist: Vahe Yeremyan Work: Original Painting, Handmade Artwork, One of a Kind Medium: Acrylic on Canvas Year: 2022 Style: Abstract Art, Subject: Century Wall, Size: 40" x 55" x ...Category

2010s Impressionist Landscape Paintings

MaterialsAcrylic, Canvas

- Harbor Pearl, Abstract Original Painting, Ready to HangBy Vahe YeremyanLocated in Granada Hills, CAArtist: Vahe Yeremyan Work: Original Painting, Handmade Artwork, One of a Kind Medium: Acrylic on Canvas Year: 2022 Style: Abstract Art, Subject: Harbor Pearl, Size: 41" x 55" x ...Category

2010s Impressionist Landscape Paintings

MaterialsAcrylic, Canvas

- Future Event, Abstract, Large size, Original Painting, Ready to HangBy Vahe YeremyanLocated in Granada Hills, CAArtist: Vahe Yeremyan Work: Original Painting, Handmade Artwork, One of a Kind Medium: Acrylic on Canvas Year: 2022 Style: Abstract Art, Subject: Future Event, Size: 40" x 67" x ...Category

2010s Impressionist Landscape Paintings

MaterialsAcrylic, Canvas