Items Similar to "Bring Ya to the Brink" Cyndi Lauper - based on a Polaroid Original

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 3

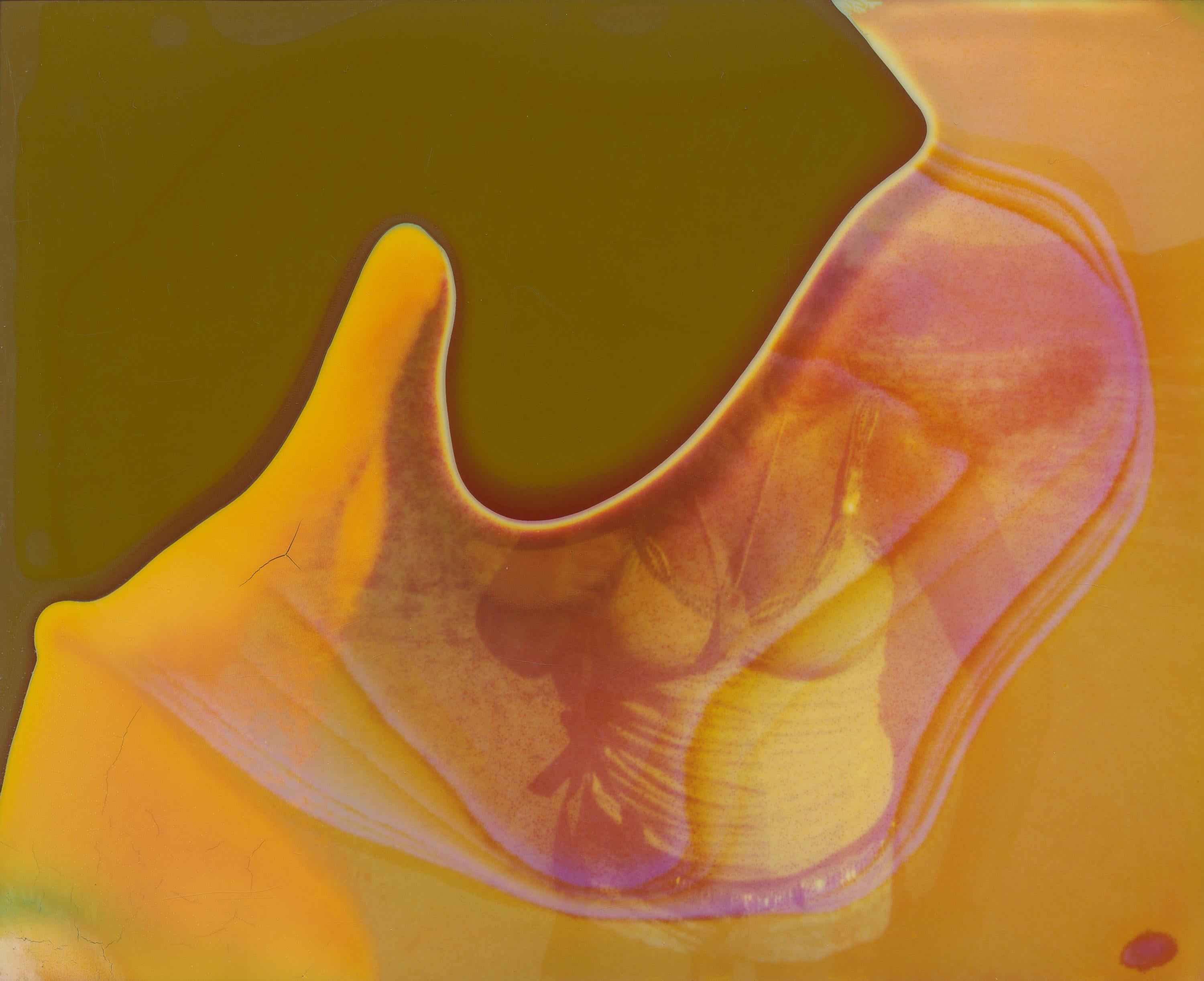

Stefanie Schneider"Bring Ya to the Brink" Cyndi Lauper - based on a Polaroid Original2009

2009

$800

£610.42

€694.40

CA$1,123.46

A$1,229.49

CHF 649.68

MX$14,674.79

NOK 8,290.70

SEK 7,582.52

DKK 5,186.81

About the Item

Bring Ya to the Brink (Cyndi Lauper record Album) - 2016,

50x49cm,

Edition of 10, plus 2 Artist Proofs.

Archival C-Print based on the Polaroid.

Signature label and Certificate.

Artist inventory number: 11003.

Not mounted.

Stefanie Schneider shot Cyndi Lauper's record cover for 'Bring Ya to the Brink'. The Shoot was documented by Arte TV. Metropolis, Arte / ZDF: “Stefanie Schneider meets Cindy Lauper”, 11/05/08

Stefanie Schneider was interviewed for the Instant Dreams Documentary

When did you first decide to work with Polaroids? Why do Polaroids seem to be so well-tuned to our (artistic) senses, perception and minds?

I started using expired Polaroid film in 1996. It has the most beautiful quality and encapsulates my vision perfectly. The colors on one hand, but then the magic moment of witnessing the image appear. Time seems to stand still, and the act of watching the image develop can be shared with the people around you. It captures a moment, which becomes the past so instantly that the decay of time is even more apparent; – it gives the image a certain sentimentality. The Polaroid moment is an original every time.

Why use a medium from the past?

For me, analog has always been there in the present. For the new generation, analog is interesting because it's new to them. I understand that people growing up in a digital age will wonder about its usefulness, but it's theirs to recover if they want to. When I first started working with Polaroid, it wasn't the past. It was a partially forgotten medium, but it existed nonetheless. It is mine by choice. There is no substitute for tangible beauty.

Is it imperfect?

The imperfect perfection in a “wabi-sabi” kind of way.

Wabi-sabi (侘寂) represents a comprehensive Japanese world view or aesthetic centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. The aesthetic is sometimes described as one of beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete".[1]

'If an object or expression can bring about, within us, a sense of serene melancholy and a spiritual longing, then that object could be said to be wabi-sabi' [2] 'Wabi-sabi nurtures all that is authentic by acknowledging three simple realities: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.'[3]

Is the Polaroid photograph recognizable or even sometimes cliché?

Absolutely! There's something cliché about the way I'm showing the American Dream. I live it myself, trying to find perfection in an imperfect world. Reaching for the horizon. The dream is broken; the cliché tumbles. There are different ways to involve an audience. You could make movies like Harmony Korine's "Gummo", a masterpiece in my view, which would estrange a large part of the audience. A certain film education is a prerequisite. Or you can start with clichés, the audience then feels safe, which lures them into the depth of your world without them even knowing it or understanding where exactly they are being led to. Appealing to emotions and the sub-conscious. Normal, Change, New Normal.

You continually revisit the landscape of the American West in your work. What draws you back to this scene?

Southern California represents a dream to me. The contrast of Northern Germany, where I grew up, to the endless sunshine of Los Angeles was what first attracted me. The American West is my dream of choice. Wide, open spaces give perspectives that articulate emotions and desires. Isolation feeds feelings of freedom or sometimes the pondering of your past. The High Desert of 29 Palms has very clear and vivid light, which is vital. Expired Polaroid film produces 'imperfections' that I would argue mirrors the decline of the American dream. These so called 'imperfections' illustrate the reality of that dream turning into a nightmare. The disintegration of Western society.

Are you playing with the temporality of the material and the value of the moment itself?

The value of the moment is paramount, for it is that moment that you're trying to transform. All material is temporary, it's relative, and time is forever.

Why does analog film feel more pure and intuitive?

It's tangible and bright and represents a single moment.

The digital moment may stay in the box (the hard drive / camera / computer etc.) forever, never to be touched, put into a photo album, sent in a letter, or hung on a wall. Printing makes it an accomplishment.

The analog world is more selective, creating images of our collective memory.

The digital worldwide clicking destroys this moment. The generation without memories due to information overload and hard drive failures. Photo albums are a thing of the past.

Why does it feel this way?

That's how the human instinct works.

When I was a child, every picture been taken was a special moment. Analog photographic film as well as Super-8 material were expensive treasures. My family's memories were created by choosing certain moments in time. There was an effort behind the picture. The roll of film might wait months inside the camera before it was all used. From there, the film required developing, which took more time, and finally, when the photos were picked up from the shop, the memories were visited again together as a family. Who knew then, how fleeting these times were. Shared memories was a ritual.

What's your philosophy behind the art of Polaroid pictures?

The 'obsolete' is anything but obsolete. Things are not always as they appear, and there are hidden messages. Our memories and our dreams are under-valued. It is there that real learning and understanding begins by opening yourself to different perspectives.

What inspired you to use stop motion cinematography?

My work has always resembled movie stills. I remember the first time I brought a box of Polaroids and slid them onto Susanne Vielmetter's desk (my first gallery). Instantly, it became apparent that there was a story to tell. The stories grew. It was undeniable to me, that the emerging story was where I was destined to go. I've made four short films before my latest feature film, "The Girl behind the White Picket Fence". This film is 60 minutes long with over 4000 edited Polaroids. It's important to remember that our sub-conscious fills in the blanks, the parts missing from the story allow a deeper and more personal experience for the viewer. That is, if you surrender yourself and trust me as the director to lead you somewhere you might not have been before.

Why do you think it is important to own art?

'We have art in order not to die of the truth'

Nietzsche

1 Koren, Leonard (1994). Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets and Philosophers. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 1-880656-12-4.

2 Juniper, Andrew (2003). Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3482-2.

3 Powell, Richard R. (2004). Wabi Sabi Simple. Adams Media. ISBN 1-59337-178-0.

- Creator:Stefanie Schneider (1968, German)

- Creation Year:2009

- Dimensions:Height: 7.88 in (20 cm)Width: 7.88 in (20 cm)Depth: 0.12 in (3 mm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:Morongo Valley, CA

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU652315477632

Stefanie Schneider

Stefanie Schneider received her MFA in Communication Design at the Folkwang Schule Essen, Germany. Her work has been shown at the Museum for Photography, Braunschweig, Museum für Kommunikation, Berlin, the Institut für Neue Medien, Frankfurt, the Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden, Kunstverein Bielefeld, Museum für Moderne Kunst Passau, Les Rencontres d'Arles, Foto -Triennale Esslingen., Bombay Beach Biennale 2018, 2019.

About the Seller

4.9

Platinum Seller

Premium sellers with a 4.7+ rating and 24-hour response times

Established in 1996

1stDibs seller since 2017

1,050 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 1 hour

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: Morongo Valley, CA

- Return Policy

More From This Seller

View AllSubliminal (Stage of Consciousness)

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Subliminal (Stage of Consciousness) - 2007,

20x24cm,

sold out Edition of 10, Artist Proof 2/2.

Archival C-Print based on the Polaroid.

Certificate and signature label.

Inventor...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Color Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

One Day I'll Fly (Stage of Consciousness) - Polaroid

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

One Day I'll Fly (Stage of Consciousness) - 2008

20x20cm,

Edition of 10,

Archival C-Print, based on the Polaroid.

Certificate and Signature label.

Artist Inventory #6481

Not mo...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Color Photography

Materials

Photographic Film, Archival Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

Flying (Stage of Consciousness) - Polaroid, Analog

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Flying (Stage of Consciousness) - 2007

part of the 29 Palms, CA project.

20x24cm,

Edition of 10 plus 2 Artist Proofs.

Archival C-Print, based on the original Polaroid.

Certificate and Signature label.

Artist Inventory #7870.

Not mounted.

LIFE’S A DREAM

(The Personal World of Stefanie Schneider)

Projection is a form of apparition that is characteristic of our human nature, for what we imagine almost invariably transcends the reality of what we live. And, an apparition, as the word suggests, is quite literally ‘an appearing’, for what we appear to imagine is largely shaped by the imagination of its appearance. If this sounds tautological then so be it. But the work of Stefanie Schneider is almost invariably about chance and apparition. And, it is through the means of photography, the most apparitional of image-based media, that her pictorial narratives or photo-novels are generated. Indeed, traditional photography (as distinct from new digital technology) is literally an ‘awaiting’ for an appearance to take place, in line with the imagined image as executed in the camera and later developed in the dark room. The fact that Schneider uses out-of-date Polaroid film stock to take her pictures only intensifies the sense of their apparitional contents when they are realised. The stability comes only at such time when the images are re-shot and developed in the studio, and thereby fixed or arrested temporarily in space and time.

The unpredictable and at times unstable film she adopts for her works also creates a sense of chance within the outcome that can be imagined or potentially envisaged by the artist Schneider. But this chance manifestation is a loosely controlled, or, better called existential sense of chance, which becomes pre-disposed by the immediate circumstances of her life and the project she is undertaking at the time. Hence the choices she makes are largely open-ended choices, driven by a personal nature and disposition allowing for a second appearing of things whose eventual outcome remains undefined. And, it is the alliance of the chance-directed material apparition of Polaroid film, in turn explicitly allied to the experiences of her personal life circumstances, that provokes the potential to create Stefanie Schneider’s open-ended narratives. Therefore they are stories based on a degenerate set of conditions that are both material and human, with an inherent pessimism and a feeling for the sense of sublime ridicule being seemingly exposed. This in turn echoes and doubles the meaning of the verb ‘to expose’. To expose being embedded in the technical photographic process, just as much as it is in the narrative contents of Schneider’s photo-novel exposés. The former being the unstable point of departure, and the latter being the uncertain ends or meanings that are generated through the photographs doubled exposure.

The large number of speculative theories of apparition, literally read as that which appears, and/or creative visions in filmmaking and photography are self-evident, and need not detain us here. But from the earliest inception of photography artists have been concerned with manipulated and/or chance effects, be they directed towards deceiving the viewer, or the alchemical investigations pursued by someone like Sigmar Polke. None of these are the real concern of the artist-photographer Stefanie Schneider, however, but rather she is more interested with what the chance-directed appearances in her photographs portend. For Schneider’s works are concerned with the opaque and porous contents of human relations and events, the material means are largely the mechanism to achieving and exposing the ‘ridiculous sublime’ that has come increasingly to dominate the contemporary affect(s) of our world. The uncertain conditions of today’s struggles as people attempt to relate to each other - and to themselves - are made manifest throughout her work. And, that she does this against the backdrop of the so-called ‘American Dream’, of a purportedly advanced culture that is Modern America, makes them all the more incisive and critical as acts of photographic exposure.

From her earliest works of the late nineties one might be inclined to see her photographs as if they were a concerted attempt at an investigative or analytic serialisation, or, better still, a psychoanalytic dissection of the different and particular genres of American subculture. But this is to miss the point for the series though they have dates and subsequent publications remain in a certain sense unfinished. Schneider’s work has little or nothing to do with reportage as such, but with recording human culture in a state of fragmentation and slippage. And, if a photographer like Diane Arbus dealt specifically with the anomalous and peculiar that made up American suburban life, the work of Schneider touches upon the alienation of the commonplace. That is to say how the banal stereotypes of Western Americana have been emptied out, and claims as to any inherent meaning they formerly possessed has become strangely displaced. Her photographs constantly fathom the familiar, often closely connected to traditional American film genre, and make it completely unfamiliar. Of course Freud would have called this simply the unheimlich or uncanny. But here again Schneider almost never plays the role of the psychologist, or, for that matter, seeks to impart any specific meanings to the photographic contents of her images. The works possess an edited behavioural narrative (she has made choices), but there is never a sense of there being a clearly defined story. Indeed, the uncertainty of my reading here presented, acts as a caveat to the very condition that Schneider’s photographs provoke.

Invariably the settings of her pictorial narratives are the South West of the United States, most often the desert and its periphery in Southern California. The desert is a not easily identifiable space, with the suburban boundaries where habitation meets the desert even more so. There are certain sub-themes common to Schneider’s work, not least that of journeying, on the road, a feeling of wandering and itinerancy, or simply aimlessness. Alongside this subsidiary structural characters continually appear, the gas station, the automobile, the motel, the highway, the revolver, logos and signage, the wasteland, the isolated train track and the trailer. If these form a loosely defined structure into which human characters and events are cast, then Schneider always remains the fulcrum and mechanism of their exposure. Sometimes using actresses, friends, her sister, colleagues or lovers, Schneider stands by to watch the chance events as they unfold. And, this is even the case when she is a participant in front of camera of her photo-novels. It is the ability to wait and throw things open to chance and to unpredictable circumstances, that marks the development of her work over the last eight years. It is the means by which random occurrences take on such a telling sense of pregnancy in her work.

However, in terms of analogy the closest proximity to Schneider’s photographic work is that of film. For many of her titles derive directly from film, in photographic series like OK Corral (1999), Vegas (1999), Westworld (1999), Memorial Day (2001), Primary Colours (2001), Suburbia (2004), The Last Picture Show (2005), and in other examples. Her works also include particular images that are titled Zabriskie Point, a photograph of her sister in an orange wig. Indeed the tentative title for the present publication Stranger Than Paradise is taken from Jim Jarmusch’s film of the same title in 1984. Yet it would be dangerous to take this comparison too far, since her series 29 Palms (1999) presages the later title of a film that appeared only in 2002. What I am trying to say here is that film forms the nexus of American culture, and it is not so much that Schneider’s photographs make specific references to these films (though in some instances they do), but that in referencing them she accesses the same American culture that is being emptied out and scrutinised by her photo-novels. In short her pictorial narratives might be said to strip films of the stereotypical Hollywood tropes that many of them possess. Indeed, the films that have most inspired her are those that similarly deconstruct the same sentimental and increasingly tawdry ‘American Dream’ peddled by Hollywood. These include films like David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), Wild at Heart (1990) The Lost Highway...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Color Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

Untitled (Stage of Consciousness) - Polaroid

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Untitled (Stage of Consciousness) - 2008

20x20cm,

Edition of 10,

Archival C-Print, based on the Polaroid.

Certificate and Signature label.

Artist Inventory #6328

Not mounted.

...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Color Photography

Materials

Photographic Film, Archival Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

Chronometry (Stage of Consciousness) - Polaroid

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Chronometry (Stage of Consciousness) - 2008

20x20cm,

Edition of 10,

Archival C-Print, based on the Polaroid.

Certificate and Signature label.

Artist Inventory #6426

Not mounte...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Color Photography

Materials

Photographic Film, Archival Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

Living in a Dream (Till Death do us Part) - Contemporary, Polaroid, Women

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Living in a Dream (Till Death do us Part) - 2005

20x20cm,

Edition of 10,

Archival C-Print print, based on the Polaroid.

Certificate and Signature label, artist Inventory No. 9781.

Not mounted.

on offer is a piece from the movie "Till Death do us Part"

Stefanie Schneider’s Till Death Do Us Part

or “There is Only the Desert for You.”

BY DREW HAMMOND

Stefanie Schneider’s Til Death to Us Part is a love narrative that comprises three elements:

1.

A montage of still images shot and elaborated by means of her signature technique of using Polaroid formats with outdated and degraded film stock in natural light, with the resulting im ages rephotographed (by other means) enlarged and printed in such a way as to generate further distortions of the image.

2.

Dated Super 8 film footage without a sound track and developed by the artist.

3.

Recorded off-screen narration of texts written by the actors or photographic subjects, and selected by the artist.

At the outset, this method presupposes a tension between still and moving image; between the conventions about the juxtaposition of such images in a moving image presentation; and, and a further tension between the work’s juxtaposition of sound and image, and the conventional relationship between sound and image that occurs in the majority of films. But Till Death Do Us Part also conduces to an implied synthesis of still and moving image by the manner in which the artist edits or cuts the work.

First, she imposes a rigorous criterion of selection, whether to render a section as a still or moving image. The predominance of still images is neither an arbitrary residue of her background as a still photographer—in fact she has years of background in film projects; nor is it a capricious reaction against moving picture convention that demands more moving images than stills. Instead, the number of still images has a direct thematic relation to the fabric of the love story in the following sense. Stills, by definition, have a very different relationship to time than do moving images. The unedited moving shot occurs in real time, and the edited moving shot, despite its artificial rendering of time, all too 2009often affords the viewer an even greater illusion of experiencing reality as it unfolds. It is self-evident that moving images overtly mimic the temporal dynamic of reality.

Frozen in time—at least overtly—still photographic images pose a radical tension with real time. This tension is all the more heightened by their “real” content, by the recording aspect of their constitution. But precisely because they seem to suspend time, they more naturally evoke a sense of the past and of its inherent nostalgia. In this way, they are often more readily evocative of other states of experience of the real, if we properly include in the real our own experience of the past through memory, and its inherent emotions.

This attribute of stills is the real criterion of their selection in Til Death Do Us Part where consistently, the artist associates them with desire, dream, memory, passion, and the ensemble of mental states that accompany a love relationship in its nascent, mature, and declining aspects.

A SYNTHESIS OF MOVING AND STILL IMAGES BOTH FORMAL AND CONCEPTUAL

It is noteworthy that, after a transition from a still image to a moving image, as soon as the viewer expects the movement to continue, there is a “logical” cut that we expect to result in another moving image, not only because of its mise en scène, but also because of its implicit respect of traditional rules of film editing, its planarity, its sight line, its treatment of 3D space—all these lead us to expect that the successive shot, as it is revealed, is bound to be another moving image. But contrary to our expectation, and in delayed reaction, we are startled to find that it is another still image.

One effect of this technique is to reinforce the tension between still and moving image by means of surprise. But in another sense, the technique reminds us that, in film, the moving image is also a succession of stills that only generate an illusion of movement. Although it is a fact that here the artist employs Super 8 footage, in principle, even were the moving images shot with video, the fact would remain since video images are all reducible to a series of discrete still images no matter how “seamless” the transitions between them.

Yet a third effect of the technique has to do with its temporal implication. Often art aspires to conflate or otherwise distort time. Here, instead, the juxtaposition poses a tension between two times: the “real time” of the moving image that is by definition associated with reality in its temporal aspect; and the “frozen time” of the still image associated with an altered sense of time in memory and fantasy of the object of desire—not to mention the unreal time of the sense of the monopolization of the gaze conventionally attributed to the photographic medium, but which here is associated as much with the yearning narrator as it is with the viewer.

In this way, the work establishes and juxtaposes two times for two levels of consciousness, both for the narrator of the story and, implicitly, for the viewer:

A) the immediate experience of reality, and

B) the background of reflective effects of reality, such as dream, memory, fantasy, and their inherent compounding of past and present emotions.

In addition, the piece advances in the direction of a Gesammtkunstwerk, but in a way that reconsiders this synaesthesia as a unified complex of genres—not only because it uses new media that did not exist when the idea was first enunciated in Wagner’s time, but also because it comprises elements that are not entirely of one artist’s making, but which are subsumed by the work overall. The totality remains the vision of one artist.

In this sense, Till Death Do Us Part reveals a further tension between the central intelligence of the artist and the products of other individual participants. This tension is compounded to the degree that the characters’ attributes and narrated statements are part fiction and part reality, part themselves, and part their characters. But Stefanie Schneider is the one who assembles, organizes, and selects them all.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THIS IDEA (above) AND PHOTOGRAPHY

This selective aspect of the work is an expansion of idea of the act of photography in which the artistic photographer selects that which is already there, and then, by distortion, definition or delimitation, compositional and lighting emphasis, and by a host of other techniques, subsumes that which is already there to transform it into an image of the artist’s contrivance, one that is no less of the artist’s making than a work in any other medium, but which is distinct from many traditional media (such as painting) in that it retains an evocation of the tension between what is already there and what is of the artist’s making. Should it fail to achieve this, it remains, to that degree, mere illustration to which aesthetic technique has been applied with greater or lesser skill.

The way Til Death Do Us Part expands this basic principle of the photographic act, is to apply it to further existing elements, and, similarly, to transform them. These additional existing elements include written or improvised pieces narrated by their authors in a way that shifts between their own identities and the identities of fictional characters. Such characters derive partially from their own identities by making use of real or imagined memories, dreams, fears of the future, genuine impressions, and emotional responses to unexpected or even banal events. There is also music, with voice and instrumental accompaniment. The music slips between integration with the narrative voices and disjunction, between consistency and tension. At times it would direct the mood, and at other times it would disrupt.

Despite that much of this material is made by others, it becomes, like the reality that is the raw material of an art photo, subsumed and transformed by the overall aesthetic act of the manner of its selection, distortion, organization, duration, and emotional effect.

* * *

David Lean was fond of saying that a love story is most effective in a squalid visual environment. In Til Death Do Us Part, the squalor of the American desert...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Color Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

You May Also Like

To Yield. From Farbtöne Series

Located in Miami Beach, FL

Hues of colour, tones of life. Each artwork of the series shows a story, a tone, an element of existence in this world. There are countless shades to it. The images are just a select...

Category

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Materials

Rag Paper, Archival Pigment

Lest all of this may never be. Color photography

Located in Miami Beach, FL

Starting with photographic base elements, such as the figure or the landscape, Haider transforms the scenery into a surreal world through heavy post-production. She uses photographs,...

Category

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Materials

Archival Pigment

Lina Redford 02

By Eric Ceccarini

Located in New York, NY

This artwork is offered in 3 sizes. The price of the artwork increases with the edition. Please contact us to inquire about the current edition number, availability, and price.

86"x59", Edition of 3

65"x43", Edition of 9

45"x30", Edition of 6

"The Painters Project" by Eric Ceccarini is an ongoing collection of collaborations with painters and models that give birth to a number of distinctive photographs. Ceccarini offers the artists the opportunity to collaborate with some of the very best models he has worked with throughout his career to create an array of spectacular images. The Artist brings his own creative universe, techniques and palette, the Model their personality and body language. The model and artist interaction is key to the process. The temporary nature of the painting on human skin is captured and immortalized through Ceccarini’s lens to create the photographic artwork.

Eric sets himself apart from others by shunning technical artifice and working in natural light, outside the studio. This results in soft, velvety, almost painterly images that amaze.

Eric is a Belgian artist born in 1965. He gained a degree in photography from INFAC, Brussels in 1987, and has since then been a fashion photographer working with many of the top houses. Chopard, Elle, Marie-Claire, L’Oréal, Levi’s, Coca Cola, Virgin, Saab, Delvaux, Lowe Lintas and Ogilvy are just some of Ceccarini’s high-profile clients.

Keywords: Photography, painting, model, contemporary, collaboration, women, paint, writing, shapes, black, white, blue, nude, body, beauty, emotion, pride, belgium, colors, bright, silhouette, french art, portrait, nude, body, portrait, thick layers, material, lina redford...

Category

2010s Other Art Style Color Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, Digital, Archival Pigment, Digital P...

Price Upon Request

Untitled #20

By Laura Letinsky

Located in New York, NY

from the series "Ill Form and Void Full"

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Photography

Price Upon Request

Wider dem Unbeugsamen. Color photography

Located in Miami Beach, FL

Starting with photographic base elements, such as the figure or the landscape, Haider transforms the scenery into a surreal world through heavy post-production. She uses photographs,...

Category

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Materials

Archival Pigment

Patricia Sartori 08

By Eric Ceccarini

Located in New York, NY

This artwork is offered in 3 sizes. The price of the artwork increases with the edition. Please contact us to inquire about the current edition number, availability, and price.

Size ...

Category

2010s Other Art Style Color Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, Digital, Archival Pigment, Digital P...

Price Upon Request