Items Similar to Fighting back the Darkness (Till Death do us Part) - Polaroid, Nude

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 8

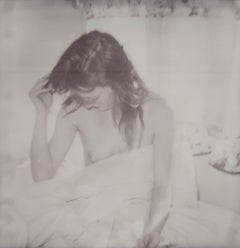

Stefanie SchneiderFighting back the Darkness (Till Death do us Part) - Polaroid, Nude2005

2005

$390

£297.71

€342.24

CA$548.80

A$610.29

CHF 320.54

MX$7,461.38

NOK 3,994.19

SEK 3,765.44

DKK 2,554.20

About the Item

Fighting back the Darkness (Till Death do us Part) - 2005

20x20cm,

Edition 9/10.

Archival C-Print, based on the Polaroid,

Certificate and Signature label.

Artist Inventory No. 9310.

Not mounted.

On offer is a piece from the movie: Till Death Do Us part

'Till death do us part' an episode of the '29 Palms, CA' project. A film shot on Polaroid stills combined with Super 8 film sequences.

'Till Death Do Us Part' is the story of two young lovers, lonely souls escaping the abuse of reality into each other. Imagine a stranger suddenly in your path, you can just be silent with, and you feel you have known her forever. This is the experience of Cristal and Margarita, that begins when Cristal picks her up hitchhiking on a lonely dessert road. A runaway from a cruel older brother and a broken family, Margarita is searching on the edge of the shadows for a home. Cristal was also a lonely child and already dangerously close to vanishing when she finds Margarita. For her it is the begging of life. When she finds Margarita, she finds herself, she feels for the first time and discovers that she is not invisible after all.

The childlike, roadside life they make together is a dream that they truly believe will last forever, and with the naive joy of beginners, they dive in, never sensing danger. When two lost souls become one and share everything, do they lose themselves further or do they become whole at last? When a girl has no home, no anchor, can she combine thrive with another? Once a human heart wakes up from isolation for the first time, enchanted by a reflection in love's mirror, can the dreamer fall asleep again, or must she wander searching to find it again forever?

Stefanie Schneider’s work is a meditation on time—its erosion, its persistence, its ability to fracture and reassemble in the mind’s eye. Like faded dreams or half-remembered encounters, her Polaroid images exist in a liminal space where past and present bleed into one another, never quite whole, never truly lost.

Her process itself is an act of defying time. The expired Polaroid film she employs carries within it the chemical scars of its own history, yielding unpredictable mutations that transform each image into an artifact of imperfection. These distortions are not merely aesthetic choices but echoes of memory—relics of moments that refuse to remain static. In an era of hyper-clarity and digital perfection, Schneider’s art invites us to embrace the ephemeral, to find beauty in the decayed and the transient.

The American West, a landscape steeped in myth and reinvention, becomes the perfect backdrop for this exploration of time’s paradoxes. Her subjects—wandering figures in motels, trailer parks, and endless deserts—are suspended between nostalgia and an uncertain future, much like the film she captures them on. They exist in a cinematic loop, their stories unfolding and dissolving, caught in the glow of a setting sun that never fully disappears.

But there is a deeper shift at play, one that mirrors the changing nature of artistic life itself. Before 2020, artists thrived on movement, on exposure, on a constant dialogue between places and people. Travel was a necessity, a lifeline to new influences and inspirations. Yet, in the wake of global upheaval, a hyper-isolationist existence has taken hold, where the act of creation unfolds within a contained world. Schneider’s desert sanctuary reflects this new reality—an alternate universe born from necessity, a space where time stretches and bends inward, echoing the dreamlike qualities of her work. The outside world receded, but within this solitude, another form of freedom emerged: the ability to construct a world entirely of one’s own making.

Memory, like Schneider’s images, is imperfect. It shifts, it fades, it distorts. Yet, in these imperfections, new narratives emerge—ones that feel more real than reality itself. This is the power of Schneider’s work: to remind us that time is not linear but layered, that the past is never truly past, and that every moment carries the weight of all that came before.

Her work is not just a preservation of a vanishing medium—it is a meditation on the nature of remembrance itself. In every blurred silhouette and chemical wash of color, she captures what it means to hold onto time even as it slips through our fingers, to relive and reinterpret, over and over again, the memories we think define us. Schneider’s images are time capsules, not of fixed moments, but of the way moments feel—a testament to how time warps, erases, and ultimately reveals. They are not just photographs; they are fragments of time, unraveling like film caught in the projector’s glow, forever flickering between memory and dream.

- Creator:Stefanie Schneider (1968, German)

- Creation Year:2005

- Dimensions:Height: 7.88 in (20 cm)Width: 7.88 in (20 cm)Depth: 0.04 in (1 mm)

- More Editions & Sizes:50x49cm, Edition of 10, plus 2 Artist ProofsPrice: $700

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:Morongo Valley, CA

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU652316074862

Stefanie Schneider

Stefanie Schneider received her MFA in Communication Design at the Folkwang Schule Essen, Germany. Her work has been shown at the Museum for Photography, Braunschweig, Museum für Kommunikation, Berlin, the Institut für Neue Medien, Frankfurt, the Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden, Kunstverein Bielefeld, Museum für Moderne Kunst Passau, Les Rencontres d'Arles, Foto -Triennale Esslingen., Bombay Beach Biennale 2018, 2019.

About the Seller

4.9

Platinum Seller

Premium sellers with a 4.7+ rating and 24-hour response times

Established in 1996

1stDibs seller since 2017

1,037 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 2 hours

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: Morongo Valley, CA

- Return Policy

Authenticity Guarantee

In the unlikely event there’s an issue with an item’s authenticity, contact us within 1 year for a full refund. DetailsMoney-Back Guarantee

If your item is not as described, is damaged in transit, or does not arrive, contact us within 7 days for a full refund. Details24-Hour Cancellation

You have a 24-hour grace period in which to reconsider your purchase, with no questions asked.Vetted Professional Sellers

Our world-class sellers must adhere to strict standards for service and quality, maintaining the integrity of our listings.Price-Match Guarantee

If you find that a seller listed the same item for a lower price elsewhere, we’ll match it.Trusted Global Delivery

Our best-in-class carrier network provides specialized shipping options worldwide, including custom delivery.More From This Seller

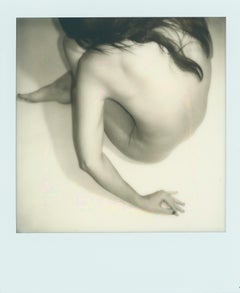

View AllYou turn from Me (Till Death do us Part) - Contemporary, Polaroid, Nude, Women

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

You turn from Me (Till Death do us Part) - 2005,

20x20cm,

Edition 1/10,

digital C-Print print, based on the Polaroid,

Certificate and Signature label.

Artist Inventory No. 9555....

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Photographic Paper, Polaroid, Color, C Print, Archival Paper

Second Thoughts (Till Death do us Part) - Contemporary, Polaroid

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Second Thoughts (Till Death do us Part) - 2005

50x49cm,

Edition of 10 plus 2 Artist Proofs.

Archival C-Print, based on the original Polaroid.

Certificate and Signature label.

A...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

$490 Sale Price

30% Off

Musing (Till Death do us Part) - Contemporary, Polaroid, Women

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Musing (Till Death do us Part) - 2005

24x20cm,

Edition of 10, plus 2 artist proofs.

Archival C-Print print, based on the Polaroid.

Certificate and Signature label, artist Invento...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Black and White Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

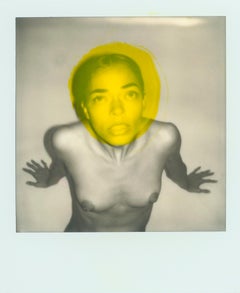

Blow my Mind (Till Death do us Part) - Contemporary, Polaroid, Nude, Women

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Blow my Mind (Till Death do us Part) - 2005,

50x49cm,

Edition of 10 plus 2 Artist Proofs.

Archival C-Print, based on the Polaroid,

Certificate and Signature label.

Artist Invent...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

Maidens (Till Death do us Part) - Contemporary, Polaroid

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Maidens (Till Death do us Part) - 2005

20x20cm,

Edition of 10 plus 2 Artist Proofs.

Archival C-Print, based on the original Polaroid.

Certificate and Signature label.

Artist In...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

Together (Till Death do us Part) - Contemporary, Polaroid

By Stefanie Schneider

Located in Morongo Valley, CA

Together (Till Death do us Part) - 2005

20x20cm,

Edition of 10 plus 2 Artist Proofs.

Archival C-Print, based on the original Polaroid.

Certificate and Signature label.

Artist I...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

You May Also Like

"Pola Girls 8" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

By Larsen Sotelo

Located in Culver City, CA

"Pola Girls 8" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

4.2" x 3.5" inch - including white Polaroid frame

3.1" x 3,1" inch - image area

C...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Polaroid

"Pola Girls 6" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

By Larsen Sotelo

Located in Culver City, CA

"Pola Girls 6" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

4.2" x 3.5" inch - including white Polaroid frame

3.1" x 3,1" inch - image area

...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Polaroid

"Pola Girls 12" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

By Larsen Sotelo

Located in Culver City, CA

"Pola Girls 12" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

4.2" x 3.5" inch - including white Polaroid frame

3.1" x 3,1" inch - image area

...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Polaroid

"Pola Girls 15" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

By Larsen Sotelo

Located in Culver City, CA

"Pola Girls 15" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

4.2" x 3.5" inch - including white Polaroid frame

3.1" x 3,1" inch - image area

...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Polaroid

"Pola Girls 11" Unique Polaroid Photography by Larsen Sotelo

By Larsen Sotelo

Located in Culver City, CA

"Pola Girls 11" Unique Polaroid Photography by Larsen Sotelo

4.2" x 3.5" inch - including white Polaroid frame

3.1" x 3,1" inch - image area

Comes with A...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Polaroid

"Pola Girls 7" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

By Larsen Sotelo

Located in Culver City, CA

"Pola Girls 7" Nude Polaroid Photography - Unique piece by Larsen Sotelo

4.2" x 3.5" inch - including white Polaroid frame

3.1" x 3,1" inch - image area

C...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Nude Photography

Materials

Polaroid