Items Similar to Turbulent Communication Computer Aided Graphic Drawing by Artist Aldo Giorgini

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 6

Turbulent Communication Computer Aided Graphic Drawing by Artist Aldo Giorgini

$5,500

$10,00044% Off

£4,264.54

£7,753.7044% Off

€4,836.61

€8,793.8344% Off

CA$7,884.01

CA$14,334.5744% Off

A$8,574.04

A$15,589.1744% Off

CHF 4,517

CHF 8,212.7244% Off

MX$104,133.38

MX$189,333.4244% Off

NOK 56,787.79

NOK 103,250.5244% Off

SEK 53,233.96

SEK 96,789.0244% Off

DKK 36,311.85

DKK 66,021.5444% Off

About the Item

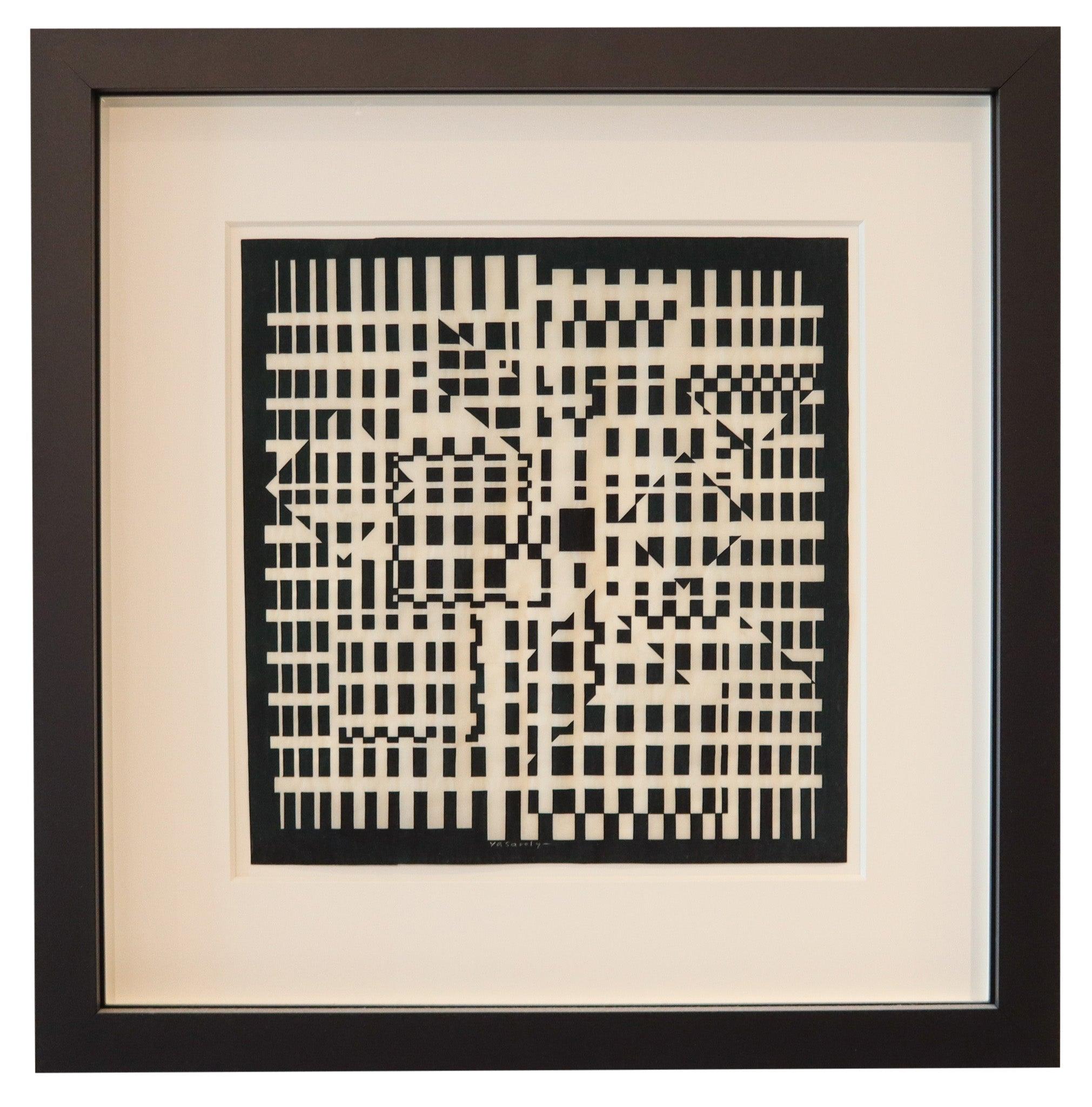

This is a rare original "artist's proof" computer-aided drawing by graphic artist Aldo Giorgini. The drawing, entitled "Turbulent Communication", was designed using his "Fields" computer program developed in Fortaran at Purdue University in 1975. The fourth picture in this listing shows the final iteration of this piece as featured in the 1985 publishing of "Computer Graphics-Computer Art" by Herbert W. Franke (notice the rotated black square background). Picture 5 shows Aldo himself in his studio circa 1975. Giorgini is considered by many to be one of the founding fathers of computer graphic art and this piece is a wonderful, one-of-a-kind example of his ground-breaking work.

Artist's process: This piece was created by taking a plot from the original Fields computer design, hand-inking the black areas, creating an electro-static copy of the painting, creating a silkscreen, then printing resulting image as a final serigraph.

A brief background on the artist:

Giorgini was born in Voghera, in the province of Pavia (northern Italy). He was a high school classmate of fashion designer Valentino, who was also a student of design of Ernestina Salvadeo, Giorgini's maternal aunt.

Formally trained by Italian Futurist painter-sculptor Ambrogio Casati, Giorgini stayed on with his mentor as an apprentice, and assisted in the restoration of Classic works by old masters damaged during the Second World War. Simultaneously attending university coursework outside of his work in the arts, Giorgini earned a doctorate in Mechanical Engineering from Politecnico di Torino before travelling to the United States on a Fulbright Scholarship. There, Giorgini earned a second doctorate, this time a Ph.D. in Civil Engineering from Colorado State University, and accepted a professorial position in the School of Civil Engineering at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. He moved to Lafayette, Indiana, on 22 December 1968.

At Purdue University, he won several awards and distinctions as an outstanding teacher of fluid mechanics and engineering mathematics at the graduate and undergraduate levels. He regularly included aesthetics lectures in his engineering courses, saying that "to be technical and scientific does not preclude a concern for the beauty and art of image and form. Architecture and engineering both occupy the same continuum: mathematics can be beautiful, and shapes can be useful."

Once established in this new position, Giorgini resumed his artistic work, combining his technical expertise with computers from his engineering training with his background in the visual arts, thereby becoming one of the first computer artists.

His pioneering computer art was generated on the Purdue University mainframe computer (CDC) and printed onto large Mylar sheets using Calcomp printers. Giorgini would then hand-ink the works of art to complete the works he called examples of "computer-aided art".

This Q & A letter written by Giorgini himself gives interesting insight into his life, artistic methodology, and sense of humor:

Dear Editor,

I hope you will accept my article in letter form. I think this device will allow me a freer hand than a normal article would, and, perhaps, a closer touch with the queries that you expressed in your call for papers.

My art background is, perhaps, somehow unusual if compared to the average American artist. At the age of ten, I was asked to apprentice to Carlo Ingeneri, a now well-known painter and sculptor of Decamere, Eritrea, who, to make a living, was teaching freehand drawing in the school I was attending. Initially my parents paid a fee which was later waived when my work in the shop was worth the instruction I received from the artist. World War II over, in 1949 my family moved back to Italy, where the same circumstance repeated itself. The freehand drawing instructor of the Scientific Lyceum I frequented in Voghera asked me to be his apprentice. Ambrogio Casati (this is his name) is a painter and sculptor who has worked in a number of media and has produced outstanding works which are now in high demand. He had been one of the handful of futurists that survived the ideologic condemnation of fascism and developed in a strong personal style that recalls both the Impressionists (for the subtle use of light) and the Futurists (for the special atmosphere of in fieri of his paintings).

Notwithstanding my dedication (I was spending an average of three hours a day in the studio) and my success in handling the media, I never considered seriously a future in art. The environment of my formative years (a mixture of maternal and paternal influence) had conditioned my order of achievement values roughly in the following order: Saint ? Artist ? Scientist ? Hero ? Builder ? Politician and/or Moneymaker. A realistic assessment of my talents and the crushing conditioning of the above hierarchy made me choose engineering for a career.

Since entering college I have only occasionally produced some artwork, but the dormant interest woke up four years ago, when I started developing a wet technique with enamels and acrylics that took literally two years to control. I call this process chastique (from stochastic technique).* The works done in this technique feature fantastic organic-like forms which, according to the words of Mario Contini, art critic of Eco D'Arte, Florence, Italy, are "characteristically well balanced, refined, and stimulating at the visual-interpretative level. Urging... masses full of meanings Stand out from the background and arise as introductory archetypal data and as emblematic images, either for a free fantastical enjoyment or for an exclusively aesthetical fruition, ad libitum." I still work with this technique now and then, since I think that it is rich with possibilities for visual experiences, albeit I spend most of my time free from professional activities in the direction of computer visualizations.

As it may be suspected, I started using the computer as a scientific tool. In the years 1966-67, while Postdoctoral Fellow at the National Center for Atmospheric Research I worked on numerical simulation of turbulence. The research was very demanding at the visualization level and, therefore, I started playing with the output facilities for the best graphical representation of the results of my research. I made some computer generated movies with the CRT-microfilm facility of NCAR and in the waiting time between one output and the next I made some sequences of didactical nature about Fourier Analysis. Once at Purdue, I had some graduate students in the same field, and I started 'playing around' with some of the computer drawings that were made as illustration of the research done. From here to the purposeful use of the computer as an art tool the pace was very short.

This being the origin of my computer efforts in art, it should not be surprising to discover that the way I use the computer in scientific endeavors has affected my thinking about its use for the production of art. In fluid-mechanic research by computer, the preparation of the computer programs and subroutines has always been seen by me as analogous to the design of laboratory facilities and of the instruments for physico-experimental research. I have called the complete set of programs and routines a 'numerical laboratory' for numerical 'experiments' in fluidmechanics. To be sure the time devoted to the design of the facilities and instruments (programs and subroutines) is of paramount importance, and sometimes one has to go beyond the conventional design for a true invention of instruments and facility parts. No matter how 'intoxicating' this design part, I've always tried never to lose track of the goal of the research: the experiments in fluidmechanics. The same attitude I have devoted to the 'computer visual experiments.' I have designed and invented programs and subroutines, not for their own sake but as components of the 'numerical laboratory' for the 'visual experiments.' You can see that this attitude is the same one that was implied in my mention of the chastique. In other words, in my view, programs and subroutines are the disposable part of the process of art by computer.

The prints that I send you have all been made using drawings generated with the program FIELDS, developed by myself with the help of Dr. W.C. Chen. These drawings (and some others not illustrated here) are the reason why the program was made. Other people may use this program, if they wish, (it has been published in its entirety with explanations for its use) but it must be realized that the 'numerical visual laboratory' called FIELDS, as any other program, is far less than a tool: it is literally a 'programme' with a large number of degrees of freedom for the user, but with a still larger number of degrees of freedom 'frozen in' by the designer. The user must realize that whatever output that program yields, it will reflect more the creative constraints of the designer of the program than those of the user. The user has to bend, to comply with a very general view of visual phenomena, and is bound to produce at best an original on the 'style' of the program, at worst a variation ? imitation of one of the existing outputs.

The word style has been used here with intentional critical connotations: the use of one program will guarantee the development of a 'style' (which some critics may discover as broader than the slogan-type styles which some traditional artists develop with the only non-ostensible purpose of being singled out from the crowd). In my view, this is a cheap way of getting somewhere with a minimum of effort. It is true that the development of a numerical laboratory for visual experiments is justified by the diversity of experiments that can be performed (in other words: let one day of creation be followed by six days of restful, complacent contemplation). But, in my view, these experiments should explore the region delimited by the degrees of freedom of the program, and not describe in detail the minutest variations that lead from one 'original' to the next. If one proceeds in the latter direction, a lifetime of stylistically coherent artistic production is guaranteed to follow the one day of creation.

With the above, dear Editor, I feel that I have implicitly answered several of the questions that you have asked. I will now answer explicitly some others.

"Do you have a final image in mind when your work begins?"

I think that this fundamental question should concern more the behaviorist than the art critic or the artist himself. But the question is asked over and over to any artist. He is, therefore, compelled in the direction

of introspecting himself in order to discover his modus operand!;

of reporting the eventual findings.

While the introspective phase may have its positive influence on the artist's conscious behavior, the explanatory phase may result in deleterious effects, since it may produce cliches that aim more at astounding than at reporting. (A propos, have you seen the recent television documentary by the title "Hello Dali"? Is his theatrical Apparatus just a self-made gilded cage for the dead bird that a miraculous mechanism provides with predictable motion and deja vu melody?)

As an overly simplified model for the modus operandi of an artist I offer, semi-facetiously, the following continuum between the two extremes CeMO and MeMO.

CeMO (purely Cerebral Modus Operand!)—The artist cogitat, ergo est. Visual images are entirely manipulated ... pardon ... mentipulated by the artist's mind and the result of this process is transferred, by any convenient mechanism (the artist's hand, an apprentice, a construction firm, a computer ...), into vulgar material substance (Hello Plato!).

MeMO (Memoriless Modus Operandi)—The artist can react only to what he sees in front of his eyes, without any ability to mentipulate the visual images. The gestures that ensue (hopefully intentional) modify the subject of his visual stimuli.

I think that both conventional artists and computer artists may be found spanning the whole continuum, albeit (non-interactive) computer artists may find themselves closer to CeMO than to MeMO. In my particular case, when I am operating in the computer mode, I tend to fully prefabricate the images mentally and then to render them by computer. The complexity of some of my drawings (see Turbulent Communication) usually creates some doubts about this assertion, since they are very mediate elaborations on moire patterns. Nevertheless it may not be difficult to accept the fact that a relatively large number of experiments performed on the visual effects of moire patterns can give a rather intimate familiarity with the ingredients for their design.

"Could your work be done without the aid of the computer?"

Yes, in a fashion analogous to the one of carving marble with a sponge. Since all FORTRAN instructions could be performed by other techniques, there is no doubt that one could execute the same by calculating and drawing by hand on a Cartesian plane. The difference between the two approaches lies merely in the amount of time required for the execution of the piece. The time constraint is of paramount importance in all endeavors and we are talking here of time ratios that approach some orders of magnitude. The question, nevertheless, is amenable to another interpretation which is more immediate in the following formulation: "Does your work with the computer affect the direction of your results?" This question is germane to the other: "Are your computer works related to your non-computer ones?"

I strongly believe that any one artist using two entirely different processes will achieve two sets of results that are entirely different at the purely visual level. The only liaison between the two sets of outputs is constituted by the aesthetico-formal handling of the visual material and, if at all present, by the motive substratum of the artist's activity ("what makes the artist do it").

Since the purpose of this collection of papers is to present some personal views about (computer) art, I will devote the remainder of this letter, dear Editor, to the exemplification of the above concepts with the particular case of my own works.

The motive substratum of my artistic activity is constituted by the fascination that natural forms have always exerted on me: from the extremely complex organic forms, rich of life-like attributes to the geometric forms of crystalline Formations and to the forms of the invisible fields around us. My mental projection of the visual elements that 'describe' natural forms is constituted not by their 'substance,' their being objects, but by the surfaces that delimit such forms. In other words, I am not interested in recognizable individual objects, but in recognizable forms, be they organic, straight-line geometric, or free-flowing geometric.

From this it follows that the selection of the processes for the rendition of such forms will be conditioned by the forms themselves. Furthermore, the intrinsic capabilities of the process will only focus on the typology of forms amenable to description by the process.

I end my letter, dear Editor, with the mention of my first one-man show. The show was exhibiting computer and non-computer work. The computer work was featuring black and white geometric forms, the non-computer work exhibited multicolor organic-like forms. Obvious contrasts. But to me the remark "They look like the works of two different artists" sounded novel and amusing. The schizoidal element is only superficial (like the one between the artist and the scientist). The 'motor' is one, and so is its formal creative Apparatus.

My best regards,

Aldo Giorgini

West Lafayette, Indiana

September 1975

“In my computer-aided drawings I try to create or to unravel optical illusions by complementing, with my own intervention, what the machine can do best.”

-Aldo Giorgini

“To be technical and scientific does not preclude a concern for the beauty and art of image and form. Architecture and engineering both occupy the same continuum: mathematics can be beautiful, and shapes can be useful.”

-Aldo Giorgini.

FREE HOLIDAY SHIPPING THROUGH THE END OF THE MONTH! BUY BY THE 20TH AND RECEIVE BY CHRISTMAS!

- Creator:Aldo Giorgini (Artist)

- Dimensions:Height: 40.25 in (102.24 cm)Width: 32.25 in (81.92 cm)Depth: 1.5 in (3.81 cm)

- Style:Mid-Century Modern (Of the Period)

- Place of Origin:

- Period:

- Date of Manufacture:1975

- Condition:Print and frame are in excellent condition, there is a small scratch to the plexiglass in the upper right corner (does not cover image).

- Seller Location:Lafayette, IN

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU268038191983

About the Seller

4.7

Vetted Professional Seller

Every seller passes strict standards for authenticity and reliability

Established in 1975

1stDibs seller since 2017

310 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 21 hours

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: Lafayette, IN

- Return Policy

Authenticity Guarantee

In the unlikely event there’s an issue with an item’s authenticity, contact us within 1 year for a full refund. DetailsMoney-Back Guarantee

If your item is not as described, is damaged in transit, or does not arrive, contact us within 7 days for a full refund. Details24-Hour Cancellation

You have a 24-hour grace period in which to reconsider your purchase, with no questions asked.Vetted Professional Sellers

Our world-class sellers must adhere to strict standards for service and quality, maintaining the integrity of our listings.Price-Match Guarantee

If you find that a seller listed the same item for a lower price elsewhere, we’ll match it.Trusted Global Delivery

Our best-in-class carrier network provides specialized shipping options worldwide, including custom delivery.More From This Seller

View AllLarge Oil and Acrylic on Canvas Abstract Painting by Artist Paul Aho

Located in Lafayette, IN

Wonderful large scale abstract painting by Florida artist Paul Aho. Painting features Aho's distinctive abstract/geometric silkscreen styl...

Category

Vintage 1980s American Paintings

Materials

Paint

$1,650 Sale Price

70% Off

Mid Century Modern J. T. Kalmar Franken KG Atomic 7 Chrome Table Lamp

By J.T. Kalmar

Located in Lafayette, IN

Rare "Atomic 7" model table lamp by J.T. Kalmar of Austria. The unique design is inspired by the shape of an atomic molecule and features 7 individual sockets/bulbs. This is a fant...

Category

Vintage 1970s Austrian Mid-Century Modern Table Lamps

Materials

Chrome

$2,449 Sale Price

30% Off

Huge Vintage Industrial Aluminum Neon TOYS "R" US Marquee Letter U Sign

Located in Lafayette, IN

Wonderful vintage neon letter "U" from a 1980's Toys "R" Us marquee. Letter feature a semi-polished, raw aluminum structure, white neon bulb, external powe...

Category

Vintage 1980s Mid-Century Modern Wall-mounted Sculptures

Materials

Aluminum

$1,462 Sale Price / item

24% Off

Mid-Century Modern Herman Miller Roll Top Action Office Desk by George Nelson

By George Nelson, Herman Miller

Located in Lafayette, IN

This is a wonderful early example of the Action Office Roll Top desk by George Nelson for Herman Miller.

Desk features:

Walnut roll top

(4) action drawers

Ebonized black side panels

Deep inner file space

Cast aluminum frame

Foot rest

White laminate writing surface

Power outlet...

Category

Vintage 1960s American Mid-Century Modern Desks

Materials

Aluminum, Chrome

$2,999 Sale Price

53% Off

1970s Mid Century Modern Oak Lounge Club Chairs & Coffee Table by Hans Krieks

Located in Lafayette, IN

Spectacular 1970's vintage living room set by designer Hans Krieks. Set features two lounge chairs and a matching coffe table all constructed ...

Category

Vintage 1970s American Mid-Century Modern Lounge Chairs

Materials

Fabric, Oak

$2,499 Sale Price / set

58% Off

Set of Four Mid-Century Modern Chrome K700 Paperclip Bar Stools by Haworth

By Haworth, Hugh Hamilton & Philip Salmon

Located in Lafayette, IN

Set of 4 chrome Paperclip bar stools by Haworth. Designed by Phillip Salmon, Hugh Hamilton and Rein Soosalu, the K700 stool was first produced in 1...

Category

Early 2000s Canadian Mid-Century Modern Stools

Materials

Metal, Steel, Chrome

You May Also Like

Oil painting on canvas by Aldo Giorgini 1972 titled "Pierrot Lunair"

By Aldo Giorgini

Located in None, IT

Oil painting on canvas produced by artist Aldo Giorgini in December 1972 entitled "Pierrot Lunair."

Frame size 55x45 cm.

Canvas size 40x30 cm.

CONDITION: In good, working conditi...

Category

Vintage 1970s Italian Paintings

Materials

Canvas

$1,597 Sale Price

25% Off

VICTOR VASARELY Paris 1960 Geometric Composition Ink on Rice Paper COA

By Victor Vasarely

Located in Miami, FL

Geometric composition in rice paper by Victor Vasarely (1906-1997).

This is a fantastic geometric composition created in Paris France by the op-art artist Victor Vasarely. The piece of art has been realized in black ink on paper. Great piece of art with gorgeous provenance and professionally framed with UV glass.

Victor Vasarely

He is considered the father of the Op Art, artist and was born on April 9th, 1908 in Pécs, Hungary. Internationally recognized as one of the most important artists of the 20th century, his innovations in color and optical illusion have had a strong influence on many modern artists. Spanning most of his career, our collection of his prints and sculptures explores his forays into some of his most famous works such as the plastic alphabet and other iconic periods. In 1925, Vasarely was accepted into the University of Budapest’s School of Medicine where he attended for 2 years. Deciding that he wanted to take his life in a different direction, he enrolled in the Poldini-Volkman Academy of Painting in 1927. Though a medical education might have seemed superfluous compared to his new career in art, the time that Vasarely spent in medical school gave him a strong basis in scientific method and objectivity. This basis continued to manifest in his unique style of art. After the artist's first one-man show in 1930, at the Kovacs Akos Gallery in Budapest, Vasarely moved to Paris. For the next thirteen years, he devoted himself to graphic studies. His lifelong fascination with linear patterning led him to draw figurative and abstract patterned subjects, such as his series of harlequins, checkers, tigers, and of course the Vasarely zebras...

Category

Vintage 1960s French Mid-Century Modern Contemporary Art

Materials

Paper

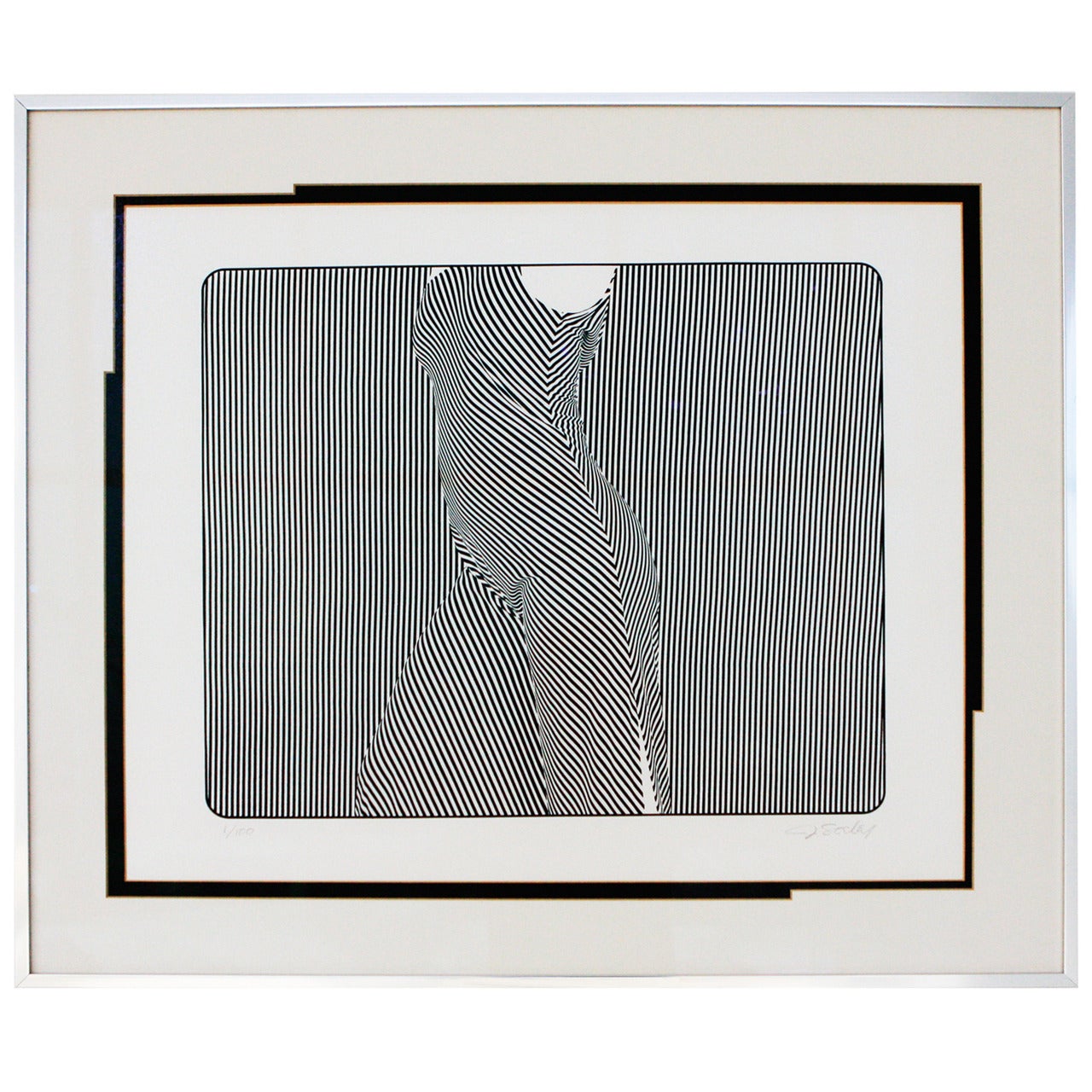

Op Art Lithograph, J Seeley

By J. Seeley

Located in New York, NY

Uniquely framed op art lithograph, signed and numbered by the artist.

First in an edition of 100.

Seeley’s images have appeared in numerous U.S. ...

Category

20th Century American Contemporary Art

Materials

Lithograph

Gerhard Uhlig 1960s op-art screen print "untitled" 1966

Located in Münster, DE

Gerhard Uhlig (1926-2015)

Screenprint "untitled", signed and numbered by hand, Ex. 47/65, created in 1966, framed behind glass

Dimensions:

Sheet size 63.5 x 58.5 cm

Frame size 90...

Category

Vintage 1960s German Modern Contemporary Art

Materials

Paint, Paper

Abstract Lithograph by Josef Albers from Formulation and Articulation

By Josef Albers

Located in Atlanta, GA

Josef Albers abstract lithograph from Formulation and Articulation, published by Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York, and Ives Sillman Inc., New Haven, circa 1972, edition of 1000, unsign...

Category

Vintage 1970s American Mid-Century Modern Prints

Materials

Glass, Wood, Paper

Artist Richard Anuszkiewicz Inward Eye #10 Op-Art Silkscreen Print, 1970, Signed

By Richard Anuszkiewicz

Located in St. Louis, MO

Richard Anuszkiewicz (1930-2020) Inward Eye #10 from the Inward Eye Series, 1970. Pronounced it ah-noo-SHKEV-ich. Silkscreen 25 19/20 × 19 3/4 inches

Edition of 100, #56/100. Acid f...

Category

Vintage 1970s American Mid-Century Modern Prints

Materials

Metal