Items Similar to Gnarled Tree - African American Artist

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 11

Charles AlstonGnarled Tree - African American Artist 1930 circa

1930 circa

About the Item

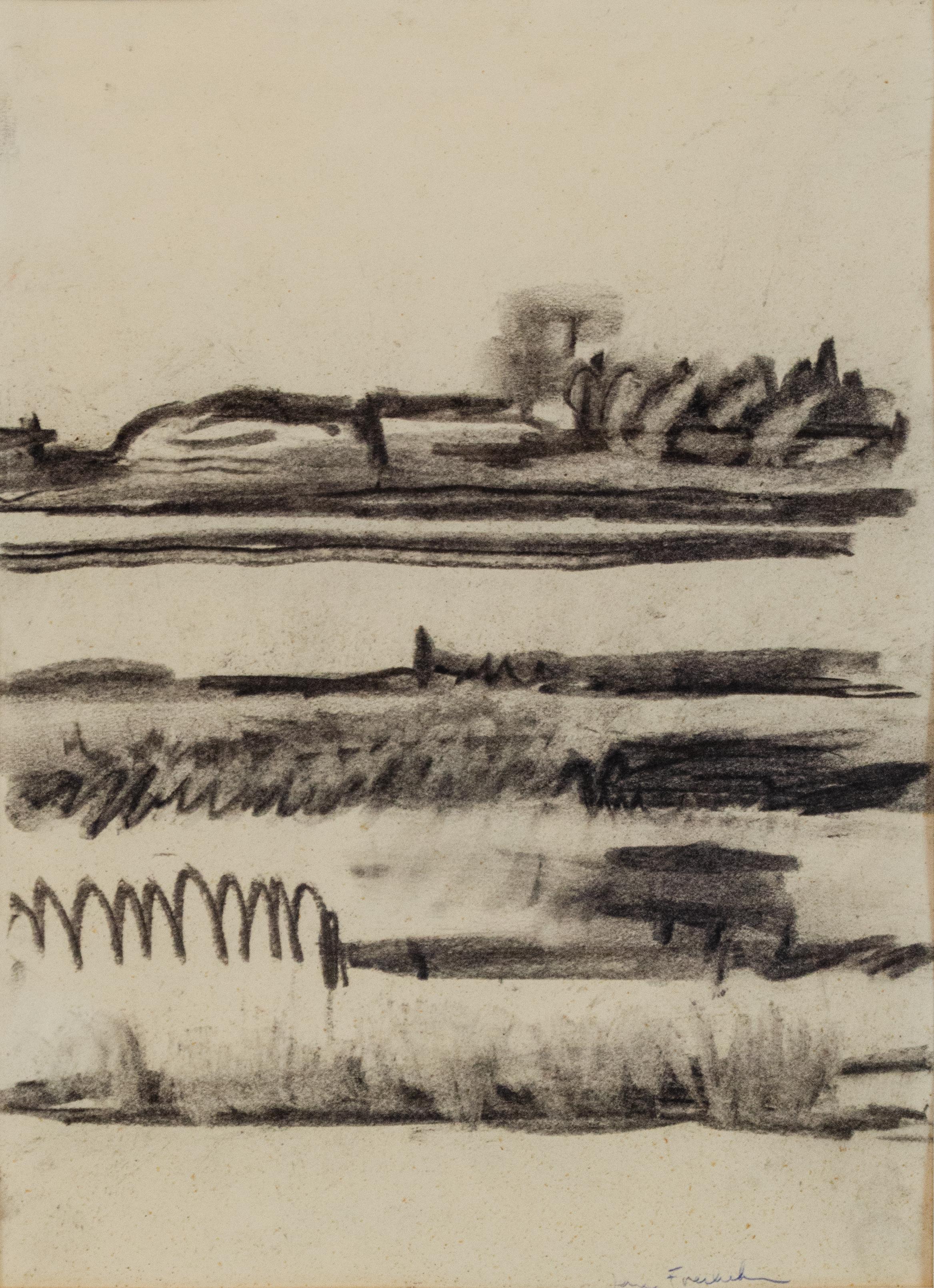

Executed in 1930, this abstract yet representational biomorphic charcoal work by African American Artist Charles Henry Alston prefigures his Abstract Expressionist paintings of the early and mid-1950s. In particular, "Troubadour" of 1955 that sold at Christie's for $189,000. In this work, Alston turns his keen eye to the nature and structure of a leafless tree. The shape of the tree and branches echoed the shape of the surrounding landscape. It's exaggerated forms allude to the American Scene Painter Thomas Hart Benton.

Signed lower right

Work is framed under glass

From Wikipedia:

Muralist and teacher who lived and worked in the New York City neighborhood of Harlem. Alston was active in the Harlem Renaissance; Alston was the first African-American supervisor for the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project. Alston designed and painted murals at the Harlem Hospital and the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building. In 1990, Alston's bust of Martin Luther King Jr. became the first image of an African American displayed at the White House.

Charles Henry Alston was born on November 28, 1907, in Charlotte, North Carolina, to Reverend Primus Priss Alston and Anna Elizabeth (Miller) Alston, as the youngest of five children.Three survived past infancy: Charles, his older sister Rousmaniere and his older brother Wendell His father had been born into slavery in 1851 in Pittsboro, North Carolina. After the Civil War, he gained an education and graduated from St. Augustine's College in Raleigh. He became a prominent minister and founder of St. Michael's Episcopal Church, with an African-American congregation. The senior Alston was described as a "race man": an African American who dedicated his skills to the furtherance of the Black race. Reverend Alston met his wife when she was a student at his school. Charles was nicknamed "Spinky" by his father, and kept the nickname as an adult. In 1910, when Charles was three, his father died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage. Locals described his father as the "Booker T. Washington of Charlotte"

In 1913, Anna Alston married Harry Bearden, Romare Bearden's uncle, making Charles and Romare cousins. The two Bearden families lived across the street from each other; the friendship between Romare and Charles would last a lifetime.

As a child, Alston was inspired by his older brother Wendell's drawings of trains and cars, which the young artist copied. Alston also played with clay, creating a sculpture of North Carolina. As an adult he reflected on his memories of sculpting with clay as a child: "I'd get buckets of it and put it through strainers and make things out of it. I think that's the first art experience I remember, making things."[1] His mother was a skilled embroiderer and took up painting at the age of 75. His father was also good at drawing, having wooed Alston's mother Anna with small sketches in the medians of letters he wrote her.

In 1915, the Bearden/Alston family moved to New York, as many African-American families did during the Great Migration. Alston's step-father, Henry Bearden, left before his wife and children in order to get work. He secured a job overseeing elevator operations and the newsstand staff at the Bretton Hotel in the Upper West Side. The family lived in Harlem and was considered middle-class. During the Great Depression, the people of Harlem suffered economically. The "stoic strength" seen within the community was later expressed in Charles’ fine art.[1] At Public School 179 in Manhattan, the boy's artistic abilities were recognized and he was asked to draw all of the school posters during his years there.

In 1917, Harry and Anna Bearden had a daughter together, Aida C. Bearden, who would later marry operatic baritone Lawrence Whisonant.

Higher education

Alston graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School, where he was nominated for academic excellence and was the art editor of the school's magazine, The Magpie. He was a member of the Arista - National Honor Society and also studied drawing and anatomy at the Saturday school of the National Academy of Art.In high school he was given his first oil paints and learned about his aunt Bessye Bearden's art salons, which stars like Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes attended. After graduating in 1925, he attended Columbia University, turning down a scholarship to the Yale School of Fine Arts.

Pvt. Alston with his art student and cousin, Romare Bearden (right), discussing one of his paintings, Cotton Workers, in 1944. Both were members of the 372nd Infantry Regiment stationed in New York City.

Alston entered the pre-architectural program but lost interest after realizing what difficulties many African-American architects had in the field. After also taking classes in pre-med, he decided that math, physics and chemistry "was not just my bag", and he entered the fine arts program. During his time at Columbia, Alston joined Alpha Phi Alpha, worked on the university's Columbia Daily Spectator, and drew cartoons for the school's magazine Jester. He also explored Harlem restaurants and clubs, where his love for jazz and black music would be fostered. In 1929, he graduated and received the Arthur Wesley Dow fellowship to study at Teachers College, where he obtained his Master's in 1931

Later life

For the years 1942 and 1943 Alston was stationed in the army at Fort Huachuca in Arizona. While working on a mural project at Harlem Hospital, he met Myra Adele Logan, then an surgical intern at the hospital. They were married on April 8, 1944. Their home, which included his studio, was on Edgecombe Avenue near Highbridge Park. The couple lived close to family; at their frequent gatherings Alston enjoyed cooking and Myra played piano. During the 1940s Alston also took occasional art classes, studying under Alexander Kostellow.

On April 27, 1977, Alston died after a long bout with cancer, just months after his wife died from lung cancer.His memorial service was held at St. Martins Episcopal Church in New York City, on May 21, 1977.

Professional career

Alston's illustration of African-American historian Carter G. Woodson for the Office of War Information

While obtaining his master's degree, Alston was the boys’ work director at the Utopia Children's House, started by James Lesesne Wells. He also began teaching at the Harlem Community Art Center, founded by Augusta Savage in the basement of what is now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Alston's teaching style was influenced by the work of John Dewey, Arthur Wesley Dow, and Thomas Munro. During this period, Alston began to teach the 10-year-old Jacob Lawrence, whom he strongly influenced. Alston was introduced to African art by the poet Alain Locke.In the late 1920s, Alston joined Bearden and other black artists who refused to exhibit in William E. Harmon Foundation shows, which featured all-black artists in their traveling exhibits. Alston and his friends thought the exhibits were curated for a white audience, a form of segregation which the men protested. They did not want to be set aside but exhibited on the same level as art peers of every skin color.

n 1938, the Rosenwald Fund provided money for Alston to travel to the South, which was his first return there since leaving as a child. His travel with Giles Hubert, an inspector for the Farm Security Administration, gave him access to certain situations and he photographed many aspects of rural life. These photographs served as the basis for a series of genre portraits depicting southern black life. In 1940, he completed Tobacco Farmer, the portrait of a young black farmer in white overalls and a blue shirt with a youthful yet serious look upon his face, sitting in front of the landscape and buildings he works on and in. That same year Alston received a second round of funding from the Rosenwald Fund to travel South, and he spent extended time at Atlanta University.

During the 1930s and early 1940s, Alston created illustrations for magazines such as Fortune, Mademoiselle, The New Yorker, Melody Maker and others. He also designed album covers for artists such as Duke Ellington and Coleman Hawkins, as well as book covers for Eudora Welty and Langston Hughes.Alston became staff artist at the Office of War Information and Public Relations in 1940, creating drawings of notable African Americans. These images were used in over 200 black newspapers across the country by the government to "foster goodwill with the black citizenry."

Alston left commercial work to focus on his own artwork, and 1950 he became the first African-American instructor at the Art Students League, where he remained on faculty until 1971.In 1950, his Painting was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and his artwork was one of the few pieces purchased by the museum.[6] He landed his first solo exhibition in 1953 at the John Heller Gallery, which represented artists such as Roy Lichtenstein. He exhibited there five times from 1953 to 1958.

In 1956, Alston became the first African-American instructor at the Museum of Modern Art, where he taught for a year before going to Belgium on behalf of MoMA and the State Department. He coordinated the children's community center at Expo 58. In 1958, he was awarded a grant from and was elected as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

In 1963, Alston co-founded Spiral with his cousin Romare Bearden, Hale Woodruff and Alvin Hollingsworth. Spiral served as a collective of conversation and artistic exploration for a large group of artists who "addressed how black artists should relate to American society in a time of segregation." Artists and arts supporters gathered for Spiral, such as Emma Amos, Perry Ferguson and Merton Simpson. This group served as the 1960s version of the 306 Group. Alston was described as an "intellectual activist", and in 1968 he spoke at Columbia about his activism. In the mid-1960s, Spiral organized an exhibition of black and white artworks, but the exhibition was never officially sponsored by the group, due to internal disagreements.[1]

In 1968, Alston received a presidential appointment from Lyndon Johnson to the National Council of Culture and the Arts. Mayor John Lindsay appointed him to the New York City Art Commission in 1969.

In 1973, he was made full professor at City College of New York, where he had taught since 1968. In 1975, he was awarded the first Distinguished Alumni Award from Teachers College.[1] The Art Student's League created a 21-year merit scholarship in 1977 under Alston's name to commemorate each year of his tenure.[3]

Painting a person and a culture

Alston shared studio space with Henry Bannarn at 306 W. 141st Street, which served as an open space for artists, photographers, musicians, writers and the like. Other artists held studio space at 306, such as Jacob Lawrence, Addison Bates and his brother Leon. During this time Alston founded the Harlem Artists Guild with Savage and Elba Lightfoot to work toward equality in WPA art programs in New York. During the early years of 306, Alston focused on mastering portraiture. His early works such as Portrait of a Man (1929) show Alston's detailed and realistic style depicted through pastels and charcoals, inspired by the style of Winold Reiss. In his Girl in a Red Dress (1934) and The Blue Shirt (1935), Alston used modern and innovative techniques for his portraits of young individuals in Harlem. Blue Shirt is thought to be a portrait of Jacob Lawrence. During this time he also created Man Seated with Travel Bag (c. 1938–40), showing the seedy and bleak environment, contrasting with work like the racially charged Vaudeville (c. 1930) and its caricature style of a man in blackface.

Inspired by his trip south, Alston began his "family series" in the 1940s. Intensity and angularity come through in the faces of the youth in his portraits Untitled (Portrait of a Girl) and Untitled (Portrait of a Boy). These works also show the influence that African sculpture had on his portraiture, with Portrait of a Boy showing more cubist features. Later family portraits show Alston's exploration of religious symbolism, color, form and space. His family group portraits are often faceless, which Alston states is the way that white America views blacks. Paintings such as Family (1955) show a woman seated and a man standing with two children – the parents seem almost solemn while the children are described as hopeful and with a use of color made famous by Cézanne. In Family Group (c. 1950) Alston's use of gray and ochre tones brings together the parents and son as if one with geometric patterns connecting them together as if a puzzle. The simplicity of the look, style and emotion upon the family is reflective and probably inspired by Alston's trip south. His work during this time has been described as being "characterized by his reductive use of form combined with a sun-hued" palette. During this time he also started to experiment with ink and wash painting, which is seen in work such as Portrait of a Woman (1955), as well as creating portraits to illustrate the music surrounding him in Harlem. Blues Singer #4 shows a female singer on stage with a white flower on her shoulder and a bold red dress. Girl in a Red Dress is thought to be Bessie Smith, whom he drew many times when she was recording and performing. Jazz was an important influence in Alston's work and social life, which he expressed in such works as Jazz (1950) and Harlem at Night.

The 1960s civil rights movement influenced his work deeply, and he made artworks expressing feelings related to inequality and race relations in the United States. One of his few religious artworks was Christ Head (1960), which had an angular "Modiglianiesque" portrait of Jesus Christ. Seven years later he created You never really meant it, did you, Mr. Charlie? which, in a similar style as Christ Head, shows a black man standing against a red sky "looking as frustrated as any individual can look", according to Alston.

Modernism

Experimenting with the use of negative space and organic forms in the late 1940s, by the mid-1950s Alston began creating notably modernist style paintings. Woman with Flowers (1949) has been described as a tribute to Modigliani. Ceremonial (1950) shows that he was influenced by African art. Untitled works during this era show his use of color overlay, using muted colors to create simple layered abstracts of still lifes. Symbol (1953) relates to Picasso's Guernica, which was a favorite work of Alston's.

His final work of the 1950s, Walking, was inspired by the Montgomery bus boycott.

The civil rights movement of the 1960s was a major influence on Alston. In the late 1950s, he began working in black and white, which he continued up until the mid-1960s, and the period is considered one of his most powerful. Some of the works are simple abstracts of black ink on white paper, similar to a Rorschach test. Untitled (c. 1960s) shows a boxing match, with an attempt to express the drama of the fight through few brushstrokes. Alston worked with oil-on-Masonite during this period as well, using impasto, cream, and ochre to create a moody cave-like artwork. Black and White #1 (1959) is one of Alston's more "monumental" works. Gray, white and black come together to fight for space on an abstract canvas, in a softer form than the more harsh Franz Kline. Alston continued to explore the relationship between monochromatic hues throughout the series which Wardlaw describes as "some of the most profoundly beautiful works of twentieth-century American art.

- Creator:Charles Alston (1907 - 1977, American)

- Creation Year:1930 circa

- Dimensions:Height: 14.5 in (36.83 cm)Width: 11.75 in (29.85 cm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:minor inpainting in upper right quadrant.

- Gallery Location:Miami, FL

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU385313697732

About the Seller

4.9

Platinum Seller

These expertly vetted sellers are 1stDibs' most experienced sellers and are rated highest by our customers.

Established in 2005

1stDibs seller since 2016

102 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 1 hour

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Ships From: Miami, FL

- Return PolicyA return for this item may be initiated within 3 days of delivery.

More From This SellerView All

- Art Deco Couple In Front of Black and White Art Deco ArchitectureLocated in Miami, FLArt Deco Illustrator Charles Perry Weimer creates a powerfully graphic depiction of a 1930s couple in front of a classic Art Deco building with a...Category

1930s Art Deco Landscape Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsPaper, Ink

- Boat SceneBy Fairfield PorterLocated in Miami, FLWatercolor on heavy paper work is unframed Signed by artist in pencil, lower right verso. Property from the estate of Anne E. C. Porter, with the estate stamp, verso. ...Category

1950s American Impressionist Landscape Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsWatercolor, Paper

- Bauhaus . Untitled (French Barque under Staysail)By Lyonel FeiningerLocated in Miami, FLBauhaus Iconic work by the master or Cubism and Expressionism Dalzell Hatfield Gallery, Los Angeles Bonhams, Exhibited: Moller Fine Art, "Precision ...Category

1940s Expressionist Landscape Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsWatercolor, Pencil

- Connecticut HillsBy Lyonel FeiningerLocated in Miami, FLExecuted in 1950 during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism and non-representational art, Feininger reduces a landscape to the bare minimums of lines and wash. Moeller Fine ArtCategory

1950s Abstract Geometric Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsWatercolor, Pencil

- Bauhaus . Untitled (French Barque under Staysail)By Lyonel FeiningerLocated in Miami, FLBauhaus Iconic work by the master or Cubism and Expressionism Dalzell Hatfield Gallery, Los Angeles Bonhams, Exhibited: Moller Fine Art, "Precision ...Category

1940s Expressionist Landscape Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsWatercolor, Pencil

- Connecticut HillsBy Lyonel FeiningerLocated in Miami, FLThis later work by Lyonel Feininger approaches almost full abstraction. It was executed in 1950 at a crucial moment in American art history. Abstract Expressionism and non-representational art were in full gear and taking the world by storm. Yet Feininger who was associated with the German expressionist groups: Die Brücke...Category

1990s Abstract Expressionist Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsIndia Ink, Watercolor

You May Also Like

- "Landscape" Seascape - Large Size -Contemporary Drawing- Made in ItalyBy Marilina MarchicaLocated in Agrigento, AGlandscape mineral oxide on papers ( Canson Paper 300gr) 75 x110 cm framed artwork, white wood frame, 91X122 cm the edge of the frame is 3.5c m Ready to Hang 2022 Artwork published ...Category

2010s Contemporary Landscape Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsCharcoal, Gouache, Paper

- "Untitled I" Jane Freilicher, Hamptons Landscape Drawing, Mid-century AbstractBy Jane FreilicherLocated in New York, NYJane Freilicher Untitled I, 1958-59 Signed lower right Charcoal on paper 11 1/2 x 8 3/4 inches Provenance: Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York Private Collection, New York Jane Freilic...Category

1950s Modern Landscape Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsPaper, Charcoal

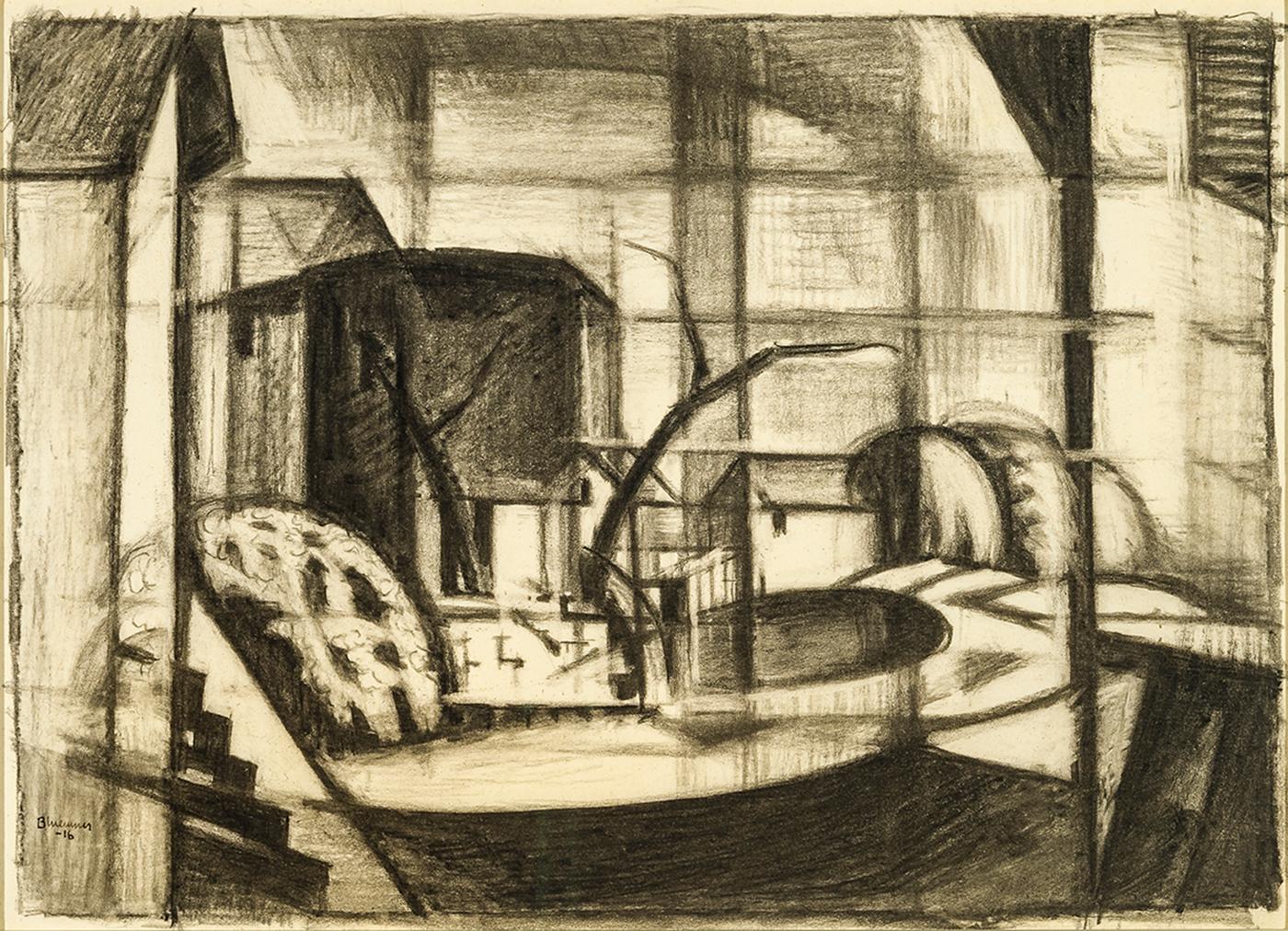

- Study for Old Canal, Red and Blue (Rockaway, Morris Canal)By Oscar Florianus BluemnerLocated in New York, NYOscar Bluemner was a German and an American, a trained architect who read voraciously in art theory, color theory, and philosophy, a writer of art criticism both in German and English, and, above all, a practicing artist. Bluemner was an intense man, who sought to express and share, through drawing and painting, universal emotional experience. Undergirded by theory, Bluemner chose color and line for his vehicles; but color especially became the focus of his passion. He was neither abstract artist nor realist, but employed the “expressional use of real phenomena” to pursue his ends. (Oscar Bluemner, from unpublished typescript on “Modern Art” for Camera Work, in Bluemner papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, as cited and quoted in Jeffrey R. Hayes, Oscar Bluemner [1991], p. 60. The Bluemner papers in the Archives [hereafter abbreviated as AAA] are the primary source for Bluemner scholars. Jeffrey Hayes read them thoroughly and translated key passages for his doctoral dissertation, Oscar Bluemner: Life, Art, and Theory [University of Maryland, 1982; UMI reprint, 1982], which remains the most comprehensive source on Bluemner. In 1991, Hayes published a monographic study of Bluemner digested from his dissertation and, in 2005, contributed a brief essay to the gallery show at Barbara Mathes, op. cit.. The most recent, accessible, and comprehensive view of Bluemner is the richly illustrated, Barbara Haskell, Oscar Bluemner: A Passion for Color, exhib. cat. [New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2005.]) Bluemner was born in the industrial city of Prenzlau, Prussia, the son and grandson of builders and artisans. He followed the family predilection and studied architecture, receiving a traditional and thorough German training. He was a prize-winning student and appeared to be on his way to a successful career when he decided, in 1892, to emigrate to America, drawn perhaps by the prospect of immediate architectural opportunities at the Chicago World’s Fair, but, more importantly, seeking a freedom of expression and an expansiveness that he believed he would find in the New World. The course of Bluemner’s American career proved uneven. He did indeed work as an architect in Chicago, but left there distressed at the formulaic quality of what he was paid to do. Plagued by periods of unemployment, he lived variously in Chicago, New York, and Boston. At one especially low point, he pawned his coat and drafting tools and lived in a Bowery flophouse, selling calendars on the streets of New York and begging for stale bread. In Boston, he almost decided to return home to Germany, but was deterred partly because he could not afford the fare for passage. He changed plans and direction again, heading for Chicago, where he married Lina Schumm, a second-generation German-American from Wisconsin. Their first child, Paul Robert, was born in 1897. In 1899, Bluemner became an American citizen. They moved to New York City where, until 1912, Bluemner worked as an architect and draftsman to support his family, which also included a daughter, Ella Vera, born in 1903. All the while, Oscar Bluemner was attracted to the freer possibilities of art. He spent weekends roaming Manhattan’s rural margins, visiting the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, and New Jersey, sketching landscapes in hundreds of small conté crayon drawings. Unlike so many city-based artists, Bluemner did not venture out in search of pristine countryside or unspoiled nature. As he wrote in 1932, in an unsuccessful application for a Guggenheim Fellowship, “I prefer the intimate landscape of our common surroundings, where town and country mingle. For we are in the habit to carry into them our feelings of pain and pleasure, our moods” (as quoted by Joyce E. Brodsky in “Oscar Bluemner in Black and White,” p. 4, in Bulletin 1977, I, no. 5, The William Benton Museum of Art, Storrs, Connecticut). By 1911, Bluemner had found a powerful muse in a series of old industrial towns, mostly in New Jersey, strung along the route of the Morris Canal. While he educated himself at museums and art galleries, Bluemner entered numerous architectural competitions. In 1903, in partnership with Michael Garven, he designed a new courthouse for Bronx County. Garven, who had ties to Tammany Hall, attempted to exclude Bluemner from financial or artistic credit, but Bluemner promptly sued, and, finally, in 1911, after numerous appeals, won a $7,000 judgment. Barbara Haskell’s recent catalogue reveals more details of Bluemner’s architectural career than have previously been known. Bluemner the architect was also married with a wife and two children. He took what work he could get and had little pride in what he produced, a galling situation for a passionate idealist, and the undoubted explanation for why he later destroyed the bulk of his records for these years. Beginning in 1907, Bluemner maintained a diary, his “Own Principles of Painting,” where he refined his ideas and incorporated insights from his extensive reading in philosophy and criticism both in English and German to create a theoretical basis for his art. Sometime between 1908 and 1910, Bluemner’s life as an artist was transformed by his encounter with the German-educated Alfred Stieglitz, proprietor of the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue. The two men were kindred Teutonic souls. Bluemner met Stieglitz at about the time that Stieglitz was shifting his serious attention away from photography and toward contemporary art in a modernist idiom. Stieglitz encouraged and presided over Bluemner’s transition from architect to painter. During the same period elements of Bluemner’s study of art began to coalesce into a personal vision. A Van Gogh show in 1908 convinced Bluemner that color could be liberated from the constraints of naturalism. In 1911, Bluemner visited a Cézanne watercolor show at Stieglitz’s gallery and saw, in Cézanne’s formal experiments, a path for uniting Van Gogh’s expressionist use of color with a reality-based but non-objective language of form. A definitive change of course in Bluemner’s professional life came in 1912. Ironically, it was the proceeds from his successful suit to gain credit for his architectural work that enabled Bluemner to commit to painting as a profession. Dividing the judgment money to provide for the adequate support of his wife and two children, he took what remained and financed a trip to Europe. Bluemner traveled across the Continent and England, seeing as much art as possible along the way, and always working at a feverish pace. He took some of his already-completed work with him on his European trip, and arranged his first-ever solo exhibitions in Berlin, Leipzig, and Elberfeld, Germany. After Bluemner returned from his study trip, he was a painter, and would henceforth return to drafting only as a last-ditch expedient to support his family when his art failed to generate sufficient income. Bluemner became part of the circle of Stieglitz artists at “291,” a group which included Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Arthur Dove. He returned to New York in time to show five paintings at the 1913 Armory Show and began, as well, to publish critical and theoretical essays in Stieglitz’s journal, Camera Work. In its pages he cogently defended the Armory Show against the onslaught of conservative attacks. In 1915, under Stieglitz’s auspices, Bluemner had his first American one-man show at “291.” Bluemner’s work offers an interesting contrast with that of another Stieglitz architect-turned-artist, John Marin, who also had New Jersey connections. The years after 1914 were increasingly uncomfortable. Bluemner remained, all of his life, proud of his German cultural legacy, contributing regularly to German language journals and newspapers in this country. The anti-German sentiment, indeed mania, before and during World War I, made life difficult for the artist and his family. It is impossible to escape the political agenda in Charles Caffin’s critique of Bluemner’s 1915 show. Caffin found in Bluemner’s precise and earnest explorations of form, “drilled, regimented, coerced . . . formations . . . utterly alien to the American idea of democracy” (New York American, reprinted in Camera Work, no. 48 [Oct. 1916], as quoted in Hayes, 1991, p. 71). In 1916, seeking a change of scene, more freedom to paint, and lower expenses, Bluemner moved his family to New Jersey, familiar terrain from his earlier sketching and painting. During the ten years they lived in New Jersey, the Bluemner family moved around the state, usually, but not always, one step ahead of the rent collector. In 1917, Stieglitz closed “291” and did not reestablish a Manhattan gallery until 1925. In the interim, Bluemner developed relationships with other dealers and with patrons. Throughout his career he drew support and encouragement from art cognoscenti who recognized his talent and the high quality of his work. Unfortunately, that did not pay the bills. Chronic shortfalls were aggravated by Bluemner’s inability to sustain supportive relationships. He was a difficult man, eternally bitter at the gap between the ideal and the real. Hard on himself and hard on those around him, he ultimately always found a reason to bite the hand that fed him. Bluemner never achieved financial stability. He left New Jersey in 1926, after the death of his beloved wife, and settled in South Braintree, Massachusetts, outside of Boston, where he continued to paint until his own death in 1938. As late as 1934 and again in 1936, he worked for New Deal art programs designed to support struggling artists. Bluemner held popular taste and mass culture in contempt, and there was certainly no room in his quasi-religious approach to art for accommodation to any perceived commercial advantage. His German background was also problematic, not only for its political disadvantages, but because, in a world where art is understood in terms of national styles, Bluemner was sui generis, and, to this day, lacks a comfortable context. In 1933, Bluemner adopted Florianus (definitively revising his birth names, Friedrich Julius Oskar) as his middle name and incorporated it into his signature, to present “a Latin version of his own surname that he believed reinforced his career-long effort to translate ordinary perceptions into the more timeless and universal languages of art” (Hayes 1982, p. 189 n. 1). In 1939, critic Paul Rosenfeld, a friend and member of the Stieglitz circle, responding to the difficulty in categorizing Bluemner, perceptively located him among “the ranks of the pre-Nazi German moderns” (Hayes 1991, p. 41). Bluemner was powerfully influenced in his career by the intellectual heritage of two towering figures of nineteenth-century German culture, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. A keen student of color theory, Bluemner gave pride of place to the formulations of Goethe, who equated specific colors with emotional properties. In a November 19, 1915, interview in the German-language newspaper, New Yorker Staats-Zeitung (Abendblatt), he stated: I comprehend the visible world . . . abstract the primary-artistic . . . and after these elements of realty are extracted and analyzed, I reconstruct a new free creation that still resembles the original, but also . . . becomes an objectification of the abstract idea of beauty. The first—and most conspicuous mark of this creation is . . . colors which accord with the character of things, the locality . . . [and which] like the colors of Cranach, van der Weyden, or Durer, are of absolute purity, breadth, and luminosity. . . . I proceed from the psychological use of color by the Old Masters . . . [in which] we immediately recognize colors as carriers of “sorrow and joy” in Goethe’s sense, or as signs of human relationship. . . . Upon this color symbolism rests the beauty as well as the expressiveness, of earlier sacred paintings. Above all, I recognize myself as a contributor to the new German theory of light and color, which expands Goethe’s law of color through modern scientific means (as quoted in Hayes 1991, p. 71). Hayes has traced the global extent of Bluemner’s intellectual indebtedness to Hegel (1991, pp. 36–37). More specifically, Bluemner made visual, in his art, the Hegelian world view, in the thesis and antithesis of the straight line and the curve, the red and the green, the vertical and the horizontal, the agitation and the calm. Bluemner respected all of these elements equally, painting and drawing the tension and dynamic of the dialectic and seeking ultimate reconciliation in a final visual synthesis. Bluemner was a keen student of art, past and present, looking, dissecting, and digesting all that he saw. He found precedents for his non-naturalist use of brilliant-hued color not only in the work Van Gogh and Cezanne, but also in Gauguin, the Nabis, and the Symbolists, as well as among his contemporaries, the young Germans of Der Blaue Reiter. Bluemner was accustomed to working to the absolute standard of precision required of the architectural draftsman, who adjusts a design many times until its reality incorporates both practical imperatives and aesthetic intentions. Hayes describes Bluemner’s working method, explaining how the artist produced multiple images playing on the same theme—in sketch form, in charcoal, and in watercolor, leading to the oil works that express the ultimate completion of his process (Hayes, 1982, pp. 156–61, including relevant footnotes). Because of Bluemner’s working method, driven not only by visual considerations but also by theoretical constructs, his watercolor and charcoal studies have a unique integrity. They are not, as is sometimes the case with other artists, rough preparatory sketches. They stand on their own, unfinished only in the sense of not finally achieving Bluemner’s carefully considered purpose. The present charcoal drawing is one of a series of images that take as their starting point the Morris Canal as it passed through Rockaway, New Jersey. The Morris Canal industrial towns that Bluemner chose as the points of departure for his early artistic explorations in oil included Paterson with its silk mills (which recalled the mills in the artist’s childhood home in Elberfeld), the port city of Hoboken, Newark, and, more curiously, a series of iron ore mining and refining towns, in the north central part of the state that pre-dated the Canal, harkening back to the era of the Revolutionary War. The Rockaway theme was among the original group of oil paintings that Bluemner painted in six productive months from July through December 1911 and took with him to Europe in 1912. In his painting journal, Bluemner called this work Morris Canal at Rockaway N.J. (AAA, reel 339, frames 150 and 667, Hayes, 1982, pp. 116–17), and exhibited it at the Galerie Fritz Gurlitt in Berlin in 1912 as Rockaway N. J. Alter Kanal. After his return, Bluemner scraped down and reworked these canvases. The Rockaway picture survives today, revised between 1914 and 1922, as Old Canal, Red and Blue (Rockaway River) in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D. C. (color illus. in Haskell, fig. 48, p. 65). For Bluemner, the charcoal expression of his artistic vision was a critical step in composition. It represented his own adaptation of Arthur Wesley’s Dow’s (1857–1922) description of a Japanese...Category

20th Century American Modern Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsPaper, Charcoal

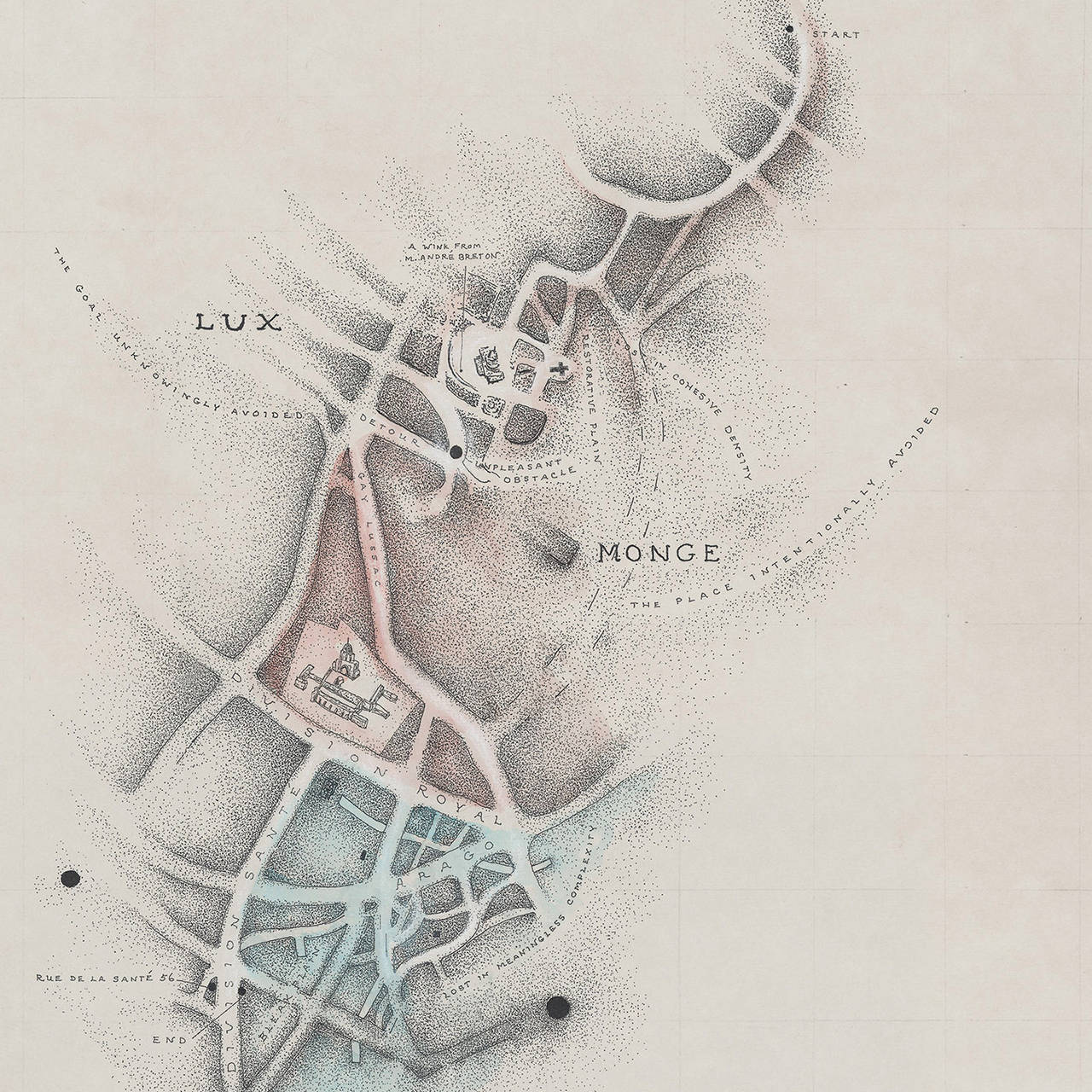

- Compulsion DriftBy Patricia SmithLocated in New York, NYwatercolor, charcoal, graphite, ink on paper 19"x25" available framed Known for her idiosyncratic cartographic explorations of the psyche and mental states, Smith incorporates ou...Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Landscape Drawings and Waterc...

MaterialsCharcoal, Graphite, Ink, Paper, Watercolor

- Early 20th Century Black White Abstracted Landscape Charcoal DrawingBy Willard Ayer NashLocated in Denver, CO"Abstract" is a charcoal on paper drawing by Willard Ayers Nash (1898-1942) of an abstracted landscape scene. Presented in a custom black frame measuring 22 x 20 x ¾ inches. Image size measures 14 ½ x 12 ¾ inches. Drawing is clean and in very good condition - please contact us for a detailed condition report. Expedited and international shipping is available - please contact us for a quote. About the Artist: Willard Ayer Nash Born Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1897 Died Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1942 Biography courtesy of Owings-Dewey Fine Art Willard Nash was frequently referred to as “the American Cézanne”. Like the French Post-Impressionist Cézanne, Nash created form with color and did wonderful work with shadows. Prior to his arrival in New Mexico, Nash painted in a formal, academic style that he learned while studying at the Detroit School of Fine Arts. However, under the tutelage of Andrew Dasburg, a fellow Santa Fe...Category

Early 20th Century Abstract Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsPaper, Charcoal

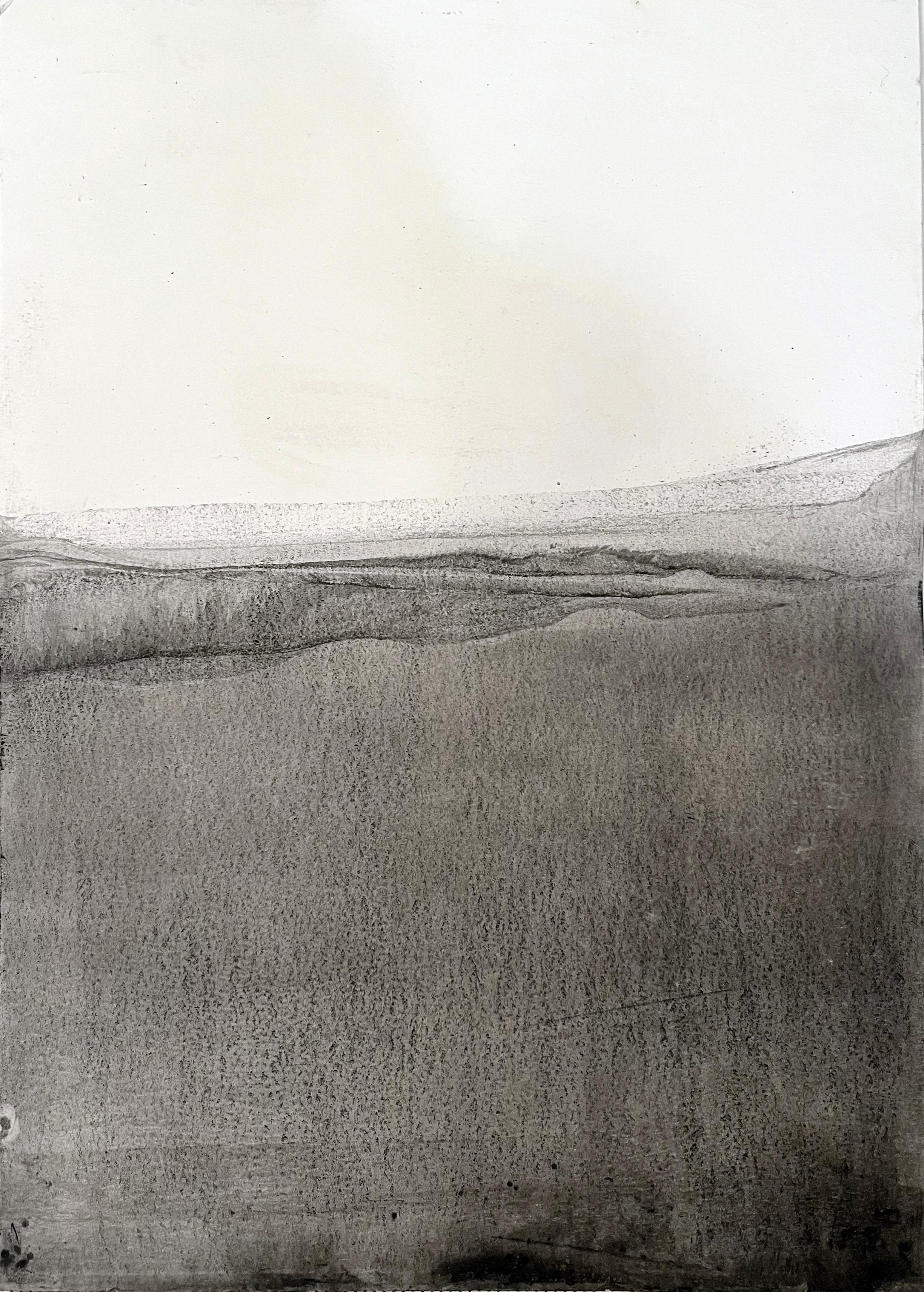

- "Black and White Landscape" Abstract Drawing , Made in ItalyBy Marilina MarchicaLocated in Agrigento, AGLandscape B/W charcoal on paper (300gr) Minimalism- Original art 30x42 cm passepartout- 35x47x05 cm this artwork is part of the solo exhibition "The Fragile Space" panelized on a ...Category

2010s Contemporary Landscape Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsPaper, Charcoal

Recently Viewed

View AllMore Ways To Browse

Under The Skin Poster

Cream And Black And White Painting

Tree Education

Set Of Small Drawings

Midcentury Abstract Trees Painting

Large Puzzle Bag

Dior Avenue Bag

Dior Bucket Bag Vintage

Dior Vintage Bucket Bag

Alpha Bucket

Dior Vintage Bag Men

Martin Luther King Bust

Small Puzzle Bag

Mens 1960 Shirts

Emma Amos

Gathered Bag

Ferguson Glass

Vintage Canvas Money Bag