Items Similar to Untitled, Still Life of Shell

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 5

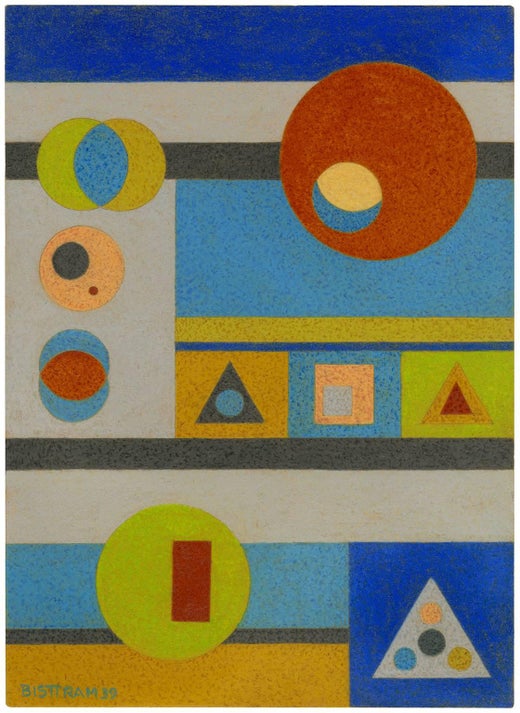

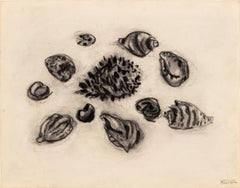

Emil BisttramUntitled, Still Life of Shell1945-1951

1945-1951

$950

£736.60

€835.41

CA$1,361.78

A$1,480.97

CHF 780.21

MX$17,986.67

NOK 9,808.80

SEK 9,194.96

DKK 6,272.05

About the Item

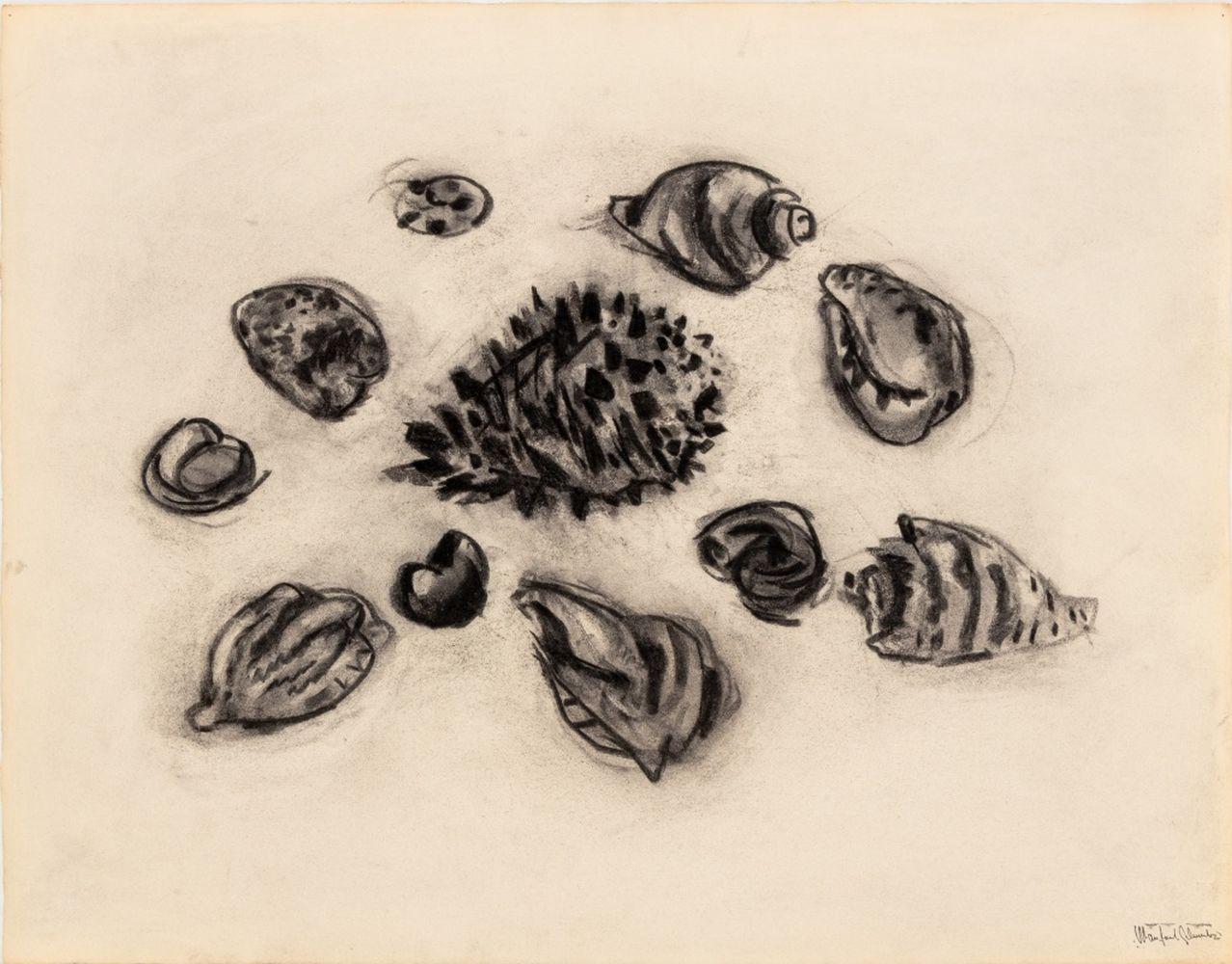

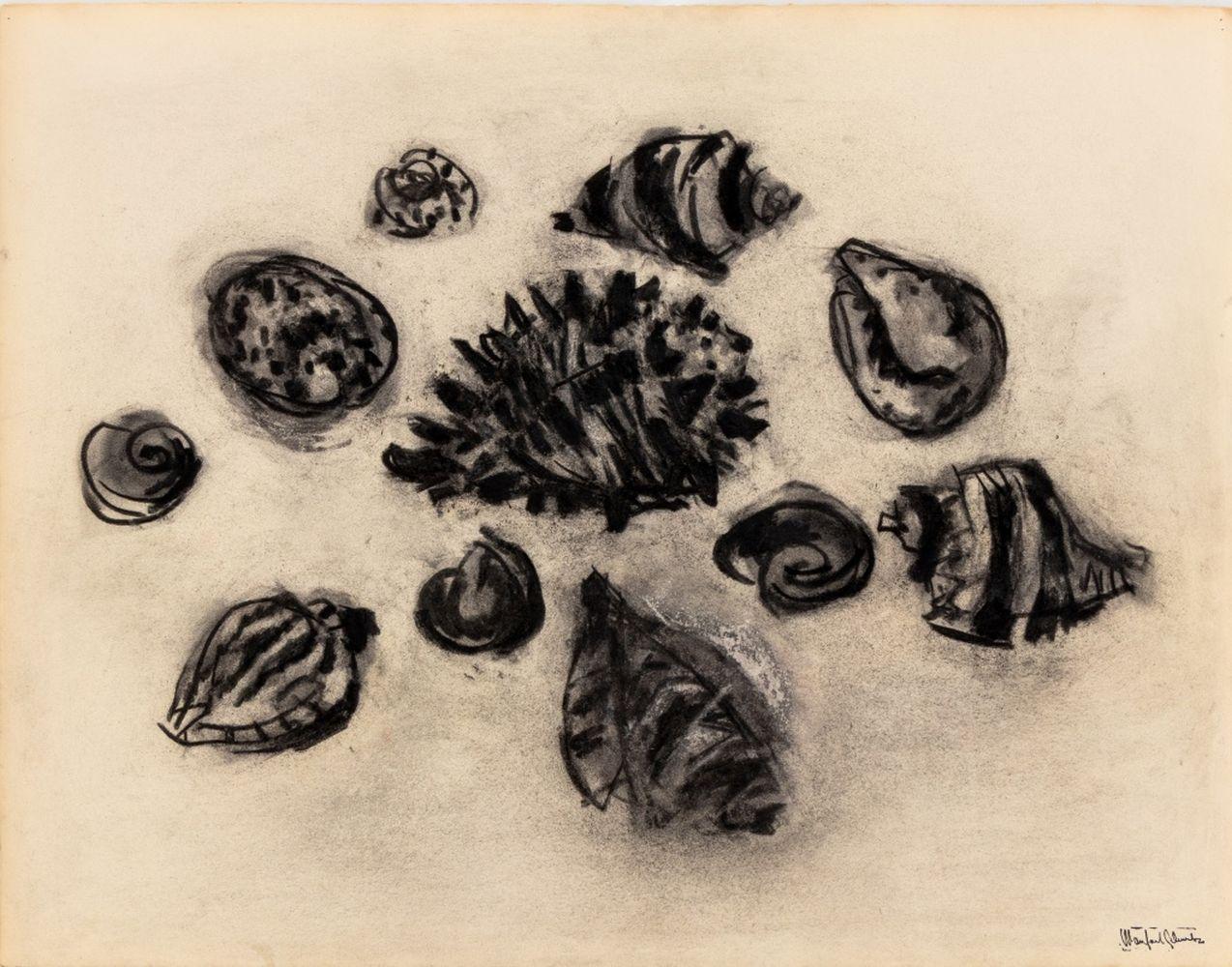

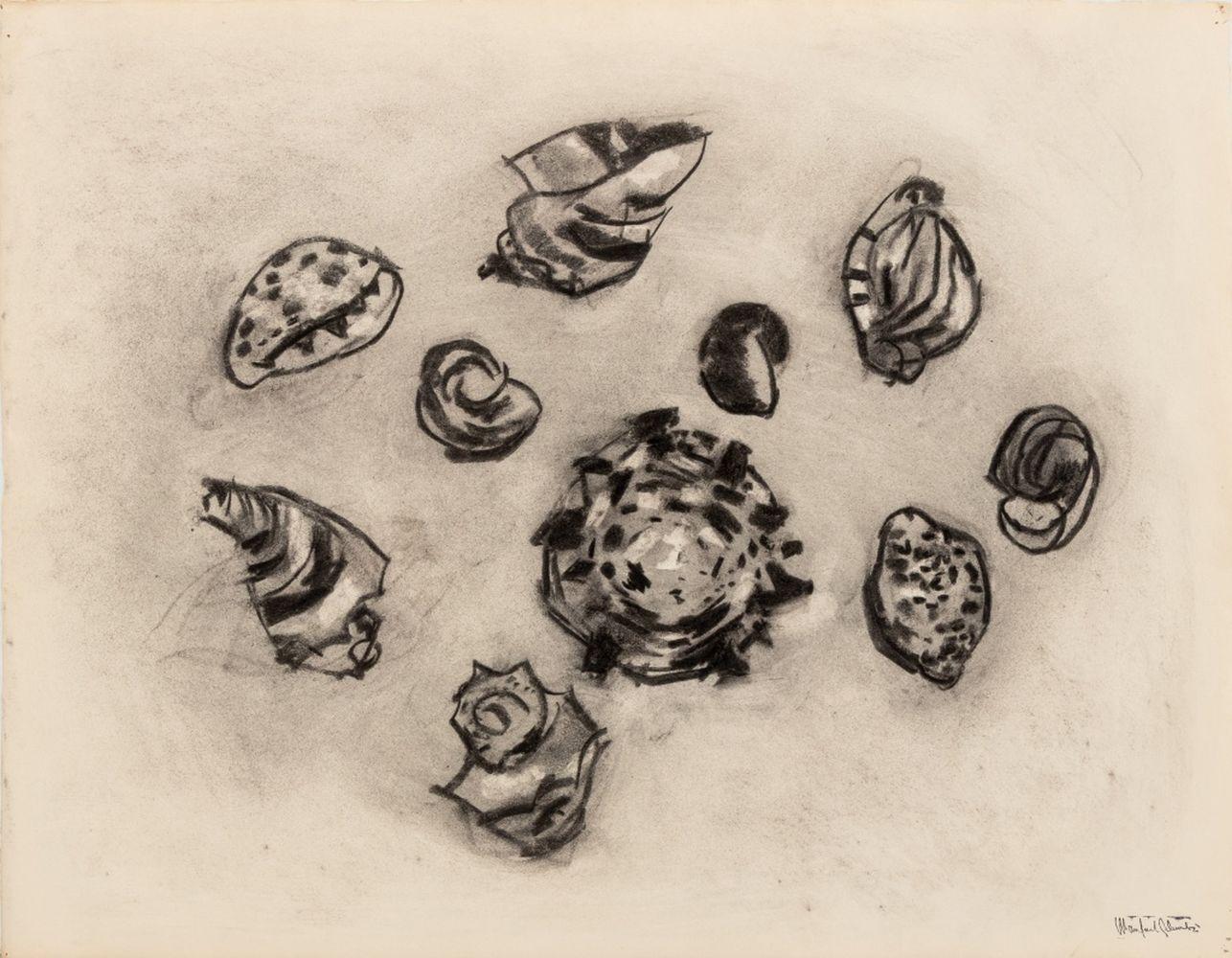

Untitled, Still Life of Shell

Graphite on paper, 1945-1951

Signed lower right in pencil "Bisttram" (see photo)

Condition: Excellent

Sheet size: 9.63 x 7 .5 inches

EMIL BISTTRAM (1895-1976) was born in Nadlak, Hungary, and baptized in the Romanian Greek Orthodox Church with the name Emilian Bistran. He immigrated to the United States in 1906 with his family. He grew up on the east side of New York and got involved with gangs and was expelled from school. Later he was enrolled in a vocational school and received some art training. He eventually worked his way up in advertising, having his own firm by 1920. He then sought out more art training under Howard Giles, who introduced him to the people and ideas who would be influential in his life – Jay Hambidge and his theory of dynamic symmetry, Denman Ross and his color theory, Nicholas Roerich, and Claude Bragdon. Bisttram made his first trip out West during the summer of 1930, visiting Taos, and then made application to the Guggenheim Foundation for a fellowship, which took him to Mexico City to study with Diego Rivera in 1931. Bisttram experimented with different styles, and by 1933 he was working with abstraction, by 1936 was making some overtly occult works, and by 1937 non-objective works influenced by Kandinsky. In 1938 he was instrumental in founding the Transcendental Painting Group made up of a group of 9 artists whose goal was to band together in order to promote their work and make a larger impact than any of them could do individually.

After World War II, TPG members went in different directions, and the Group disbanded. Bisttram went out to Phoenix (1941-1944) and then to Los Angeles (1945-1951) to teach in the winters, always returning to teach the Taos Summer School in the summers.

Emil Bisttram’s artistic career is of special interest because of the fascinating array of spiritual, philosophical, and scientific traditions he brought to bear on his painting. Profoundly spiritual and convinced that all intellectual disciplines lead to divine truth, Bisttram enriched his compositions with references to such varied subjects as electricity, rebirth, the growth of plants, the healing power of the dance, planetary forces, the fourth dimension, and the male and female principles of nature.

Bisttram’s essential goal in building his compositions, however, was personal redemption. For Bisttram, dividing space on a blank sheet of paper replicated such proportional divisions as were made by the Creator when He separated day from night, and earth from water. Bisttram’s essential belief was that harmony was proportional, and that making harmonious, proportional divisions on a sheet of paper was a productive, life-giving, redemptive enterprise that combated negativity and disharmony.

The manner that Bisttram used to proportionally divide his compositions was dynamic symmetry, a method of picture composition based on Euclidean geometry developed by Jay Hambidge (1867-1924). Bisttram used dynamic symmetry for the structure of his representational, abstract (cubist and futurist), and transcendental (non-objective) compositions. For Bisttram, dynamic symmetry functioned as a compass that guided him through the many stylistic experiments he undertook, and provides the essential coherency for his work as a whole.

Bisttram was using dynamic symmetry by 1920, when he was just beginning to establish himself as an artist. At the same time he also became interested in various spiritual systems generally associated with the occult, including theosophy, Swedenborgianism, and Rosicrucianism. By correlating these spiritual systems with dynamic symmetry, he felt that he was pictorially reconciling religion and science, which was perhaps the most important factor motivating his work. This was a conscious aim on his part and one which he expressed frequently:

Through self-discipline and contemplation, tolerance and vision he [the artist] will become the synthesizer of the reality of religion and the truth of science. (Emil Bisttram, “Art’s Revolt in the Desert,” Contemporary Arts of the South and Southwest 1, no. 2: Jan.-Feb. 1933, 11.)

Bisttram began by applying dynamic symmetry to representational compositions; after his move to Taos, New Mexico, in 1931, he began working with cubist and futurist styles, arriving at an aesthetic of pure geometric form by 1938, when he and nine others founded the Transcendental Painting Group. Tracing Bisttram’s transition from representation to abstraction through his mystical and scientific use of dynamic symmetry, provides a fruitful approach to appreciating his intentions.

The key theoretical construct with which Bisttram worked was the theory of opposites that functioned within H. P. Blavatsky’s theory of the ether, which is examined in the context of specific works of art. This principle of opposites also functioned within Swedenborgian theology, which Bisttram read in the 1920s, and in Jungian psychology, which he read in the 1930s. The link between these theories is that they all present similar methods for redemption. Bisttram’s goal of expressing these theories of opposing interrelated forces pictorially led directly to a constructivist handling of geometric forms.

During his lifetime, Bisttram was well-known across the Southwest and West. He had an impressive number of solo exhibitions at museums and university galleries, frequently won awards in group exhibitions, and was regularly invited to serve on juries. In 1931 he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to study in Mexico with Diego Rivera.

Bisttram was also active in the Taos art scene: in 1933 he was a founding member of Taos Heptagon, regarded as the first art gallery in Taos, and in 1939 organized La Fonda Gallery in the La Fonda de Taos Hotel. He participated in government mural programs, and served as supervisor for Northern New Mexico for the Treasury Relief Art Project (TRAP). He was a founding member of two associations of artists in Taos (1934, 1952), and served as president of the Taos Artists Association for two terms (1939, 1940).

Through his membership in the Transcendental Painting Group, his work came to the attention of Hilla Rebay, who included him in a number of group exhibitions at the Museum of Non-Objective Art, now the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1940, 1944, 1950).

Beginning in 1932, he ran an art school during the summers in Taos, and took private students during the winters. In 1941 he began teaching in Phoenix during the winters. He established a presence on the West Coast while operating his art school in Los Angeles (1945-1951). In 1961, he was included in the only exhibition ever devoted to dynamic symmetry, which was organized by the Rhode Island School of Design. In 1973, he was appointed to serve on the New Mexico Arts Commission, and on his eightieth birthday, the governor of New Mexico proclaimed “Emil Bisttram Day.”

Since Bisttram’s death, his work has been exhibited primarily in the context of large group exhibitions. The spiritual dimension of Bisttram’s painting and the importance of the Transcendental Painting Group were recognized by the inclusion of paintings by Bisttram and three other members – Lawren Harris, Raymond Jonson, and Agnes Pelton – in Maurice Tuchman’s The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 (1986). Spiritual painting has also been practiced by representational painters, which is shown in Cosmic Art (1975), Raymond Piper’s survey of 20th c. spiritual painting, in which Bisttram was also included.

Bisttram’s transcendental paintings, which were produced after 1936, are usually classed with the “second wave” of American abstractionists – those artists who came to maturity during the 1930s under the influence of Picasso and Kandinsky. This categorization of Bisttram is generally correct, and points to the essential interest of his work – the manner in which he made the transition from representational to abstract painting, and the relationship of his work to Kandinsky’s.

The “second wave” abstractionists have been examined in large exhibitions that in many cases include both the Transcendental Painting Group and the American Abstract Artists. The association between these two groups has been made primarily by collectors interested in 1930s abstraction. Theme & Improvisation: Kandinsky & the American Avant-Garde 1912-1950 (1992), a broad overview of these trends, provides the most comprehensive treatment of Bisttram and the Transcendental Painting Group.

Since Bisttram also worked in a representational mode using subjects related to New Mexico, he has been included in books and exhibitions devoted to the first generation of New Mexico painters. Jackson Rushing’s inclusion of a number of Bisttram’s abstract works in Native American Art and the New York Avant-Garde (1995) recognized his contribution to the development of modernist forms in American art.

Since Bisttram’s death only one solo exhibition of his works has been mounted at a museum, an exhibition of his works on paper from the Anschutz Collection at the Harwood Museum in Taos in 1983. A monograph on Bisttram was published by the dealer Walt Wiggins in 1988.

- Creator:Emil Bisttram (1895 - 1976, American, Hungarian)

- Creation Year:1945-1951

- Dimensions:Height: 9.63 in (24.47 cm)Width: 7.5 in (19.05 cm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:Fairlawn, OH

- Reference Number:Seller: FA125101stDibs: LU14016034552

Emil James Bisttram Born Hungary, 1895

Died New Mexico, 1976 Emil Bisttram was born in Hungary in 1895 and emigrated with his parents when he was eleven to America. Bisttram choose a more economically promising career in commercial art design due to his economic conditions. Bisttram opened his own art agency at the young age of twenty and during this time took classes with Leon Kroll at the Art Student League and with Jay Hambidge, an advocate of Dynamic Symmetry, at the New York School of Fine and Applied Art (renamed the Parsons School of Design). Dynamic Symmetry is a system of spacial balances and had a lifelong impact on Bisttram. Bisttram taught at Parsons from 1920 to 1925 and at the New York Master Institute of United Arts at the Roerich Museum from 1925-1930. The Institute was a spiritual inspiration to Bisttram because it advocated linking the fine arts together. His style of painting however was more influenced by Kandinsky and he began to experiment in non-objective art. Bisttram received many awards including a Guggenheim fellowship in 1931 to study mural painting. However, he decided to go to Mexico study with the great Mexican Muralist Diego Rivera. After returning from Mexico, Bisttram participated in an exhibition at the Whitney Museum for Guggenheim fellows in 1933 and received a commission to create a mural for the Taos, New Mexico courthouse. The Taos School of Art (renamed Bisttram School of Fine Art) which explored spiritualism and meditation was opened by Bisttram in 1932 where he taught some famous painters including Florence Miller Pierce. Together with Raymond Jonson and Lauren Harris, the Transcendental Painting Group was formed in Santa Fe, New Mexico from 1938-1942. This group was considered very radical for the time and the community reacted with much disdain. Bisttram continued to teach and paint and it is thought that Bisttram’s art truly represents transcendental ideas.

About the Seller

5.0

Recognized Seller

These prestigious sellers are industry leaders and represent the highest echelon for item quality and design.

Gold Seller

Premium sellers maintaining a 4.3+ rating and 24-hour response times

Established in 1978

1stDibs seller since 2013

819 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: <1 hour

Associations

International Fine Print Dealers Association

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: Akron, OH

- Return Policy

Authenticity Guarantee

In the unlikely event there’s an issue with an item’s authenticity, contact us within 1 year for a full refund. DetailsMoney-Back Guarantee

If your item is not as described, is damaged in transit, or does not arrive, contact us within 7 days for a full refund. Details24-Hour Cancellation

You have a 24-hour grace period in which to reconsider your purchase, with no questions asked.Vetted Professional Sellers

Our world-class sellers must adhere to strict standards for service and quality, maintaining the integrity of our listings.Price-Match Guarantee

If you find that a seller listed the same item for a lower price elsewhere, we’ll match it.Trusted Global Delivery

Our best-in-class carrier network provides specialized shipping options worldwide, including custom delivery.More From This Seller

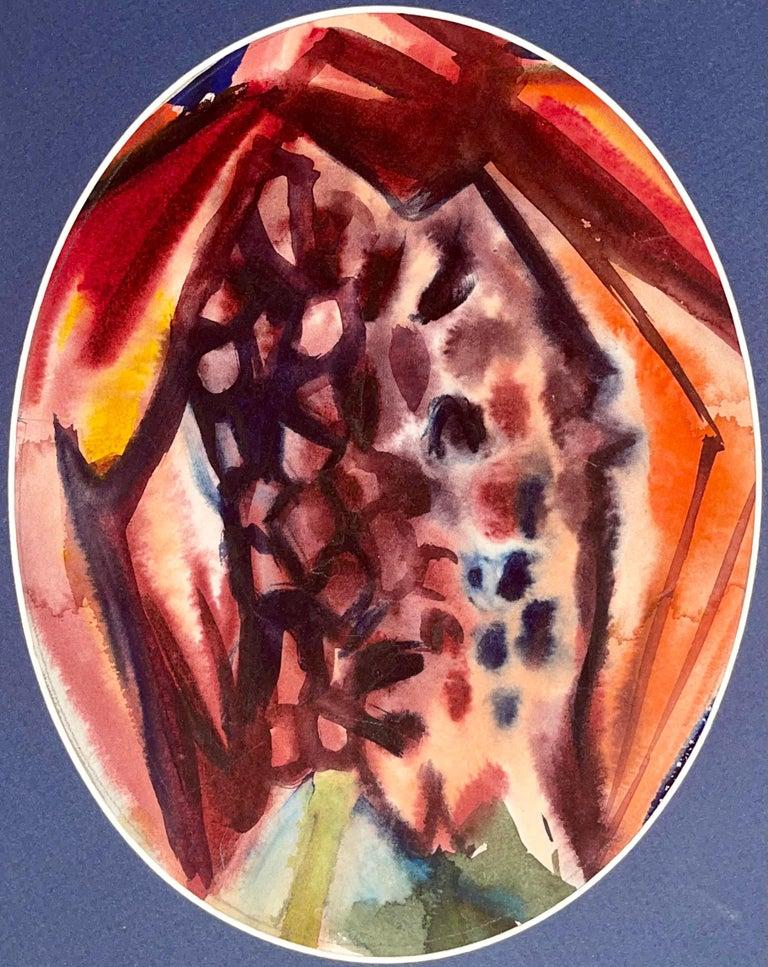

View Alluntitled (Shell #773: Interior)

Located in Fairlawn, OH

Unknown Artist, Japanese, 20th century

Unsigned

Inscription in Japanese that repeats the English

Category

20th Century Drawings and Watercolor Paintings

Materials

Watercolor

Still Life with Tromp L'Oeil

By William Sommer

Located in Fairlawn, OH

Still Life with Tromp L'Oeil

Graphite and watercolor on a book page.

Signed in ink by the artist lower right corner

(see photo)

Provenance:

Estate of the artist (Estate No. 00916 verso)

Ray Sommer (the artist's son)

Joseph M. Erdelac (No. 18 JME verso)

Book page verso is an illustration of a Durer woodcut...

Category

1920s American Modern Still-life Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Watercolor

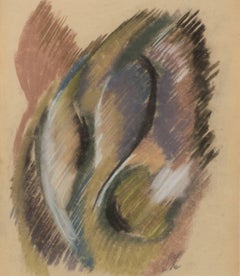

Untitled

By Leon Kelly

Located in Fairlawn, OH

Untitled

Pastel on paper, 1922

Initialed lower right (see photo)

Exhibited: Francis Nauman, Leon Kelly: Draftsman Extraordinaire, New York, April 4 - May 23, 2014.

Condition: Excell...

Category

20th Century American Modern Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Pastel

$4,000

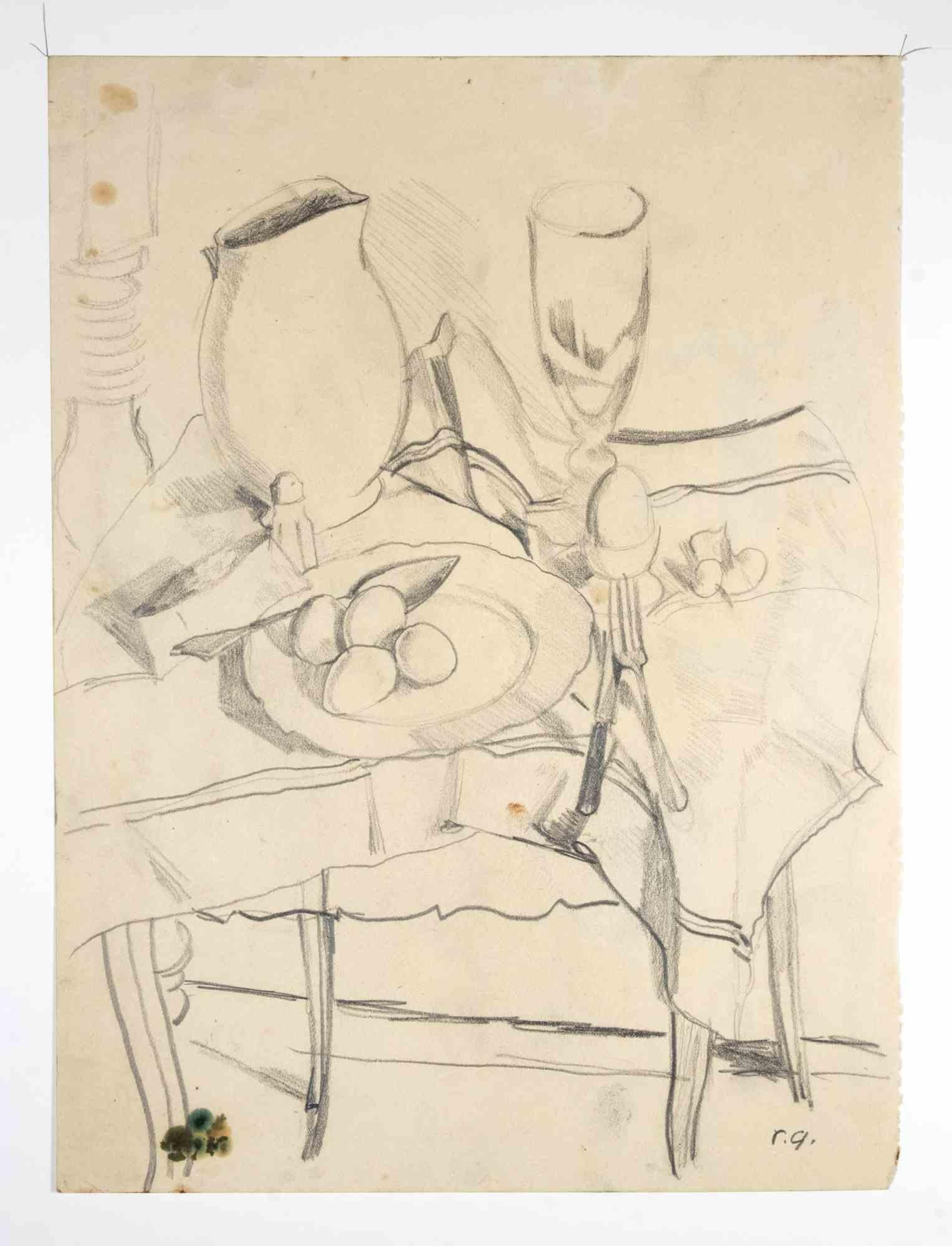

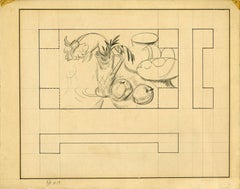

untitled (Still Life with Apples and Vase of Flowers)

By William Sommer

Located in Fairlawn, OH

[recto];untitled (Sketches for Still

Unsigned

9 1/2 x 12 inches (24.2 x 30.6 cm.)

Category

20th Century Still-life Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Graphite

Untitled

By Leon Kelly

Located in Fairlawn, OH

Untitled

Pastel on paper, 1922

Signed with the artist's initials in pencil

Provenance: Estate of the artist

Francis M. Nauman (label)

Private collection, NY

A very early abstract/cubist work by Kelly. Created while the artist was studying with Arthur Carles in Philadelphia.

Leon Kelly (October 21, 1901 – June 28, 1982) was an American artist born in Philadelphia, PA. He is most well known for his contributions to American Surrealism, but his work also encompassed styles such as Cubism, Social Realism, and Abstraction. Reclusive by nature, a character trait that became more exaggerated in the 1940s and later, Kelly's work reflects his determination not to be limited by the trends of his time. His large output of paintings is complemented by a prolific number of drawings that span his career of 50 years. Some of the collections where his work is represented are: The Metropolitan Museum in New York, The Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Boston Public Library.

Biography

Kelly was born in 1901 at home at 1533 Newkirk Street, Philadelphia, PA. He was the only child of Elizabeth (née Stevenson) and Pantaleon L. Kelly. The family resided in Philadelphia where Pantaleon and two of his cousins owned Kelly Brothers, a successful tailoring business. The prosperity of the firm enabled his father to purchase a 144-acre farm in Bucks County PA in 1902, which he named "Rural Retreat" It was here that Pantaleon took Leon to spend every weekend away from the pressures of business and from the disappointments in his failing marriage. Idyllic and peaceful memories of the farm stayed with Leon and embued his work with a love of nature that emerged later in the Lunar Series, in Return and Departure, and in the insect imagery of his Surrealist work. "If anything," he once said,"I am a Pantheist and see a spirit in everything, the grass, the rocks, everything."

At thirteen, Leon left school and began private painting lessons with Albert Jean Adolphe, a teacher at the School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts) in Philadelphia. He learned technique by copying the works of the old masters and visiting the Philadelphia Zoo, where he would draw animals. Drawings done in 1916 and 1917 of elephants, snakes and antelope, as well as copies of old master paintings by Holbein and Michelangelo, heralded an impressive emerging talent. In 1917, he studied sculpture with Alexander Portnoff but his studies came to an abrupt halt with the start of World War I. Being too young to enlist, he joined the Quartermaster Corp at the Army Depot in Philadelphia, where he served for more than a year loading ships with supplies and, along with other artists, working on drawings for camouflage.

By 1920, the family's fortunes drastically changed. His father's business had failed due to the introduction of ready made clothing and his marriage, unhappy from the beginning, dissolved. Broken by circumstance Pantaleon left Philadelphia to begin a wandering existence looking for work leaving Leon to support his mother and grandmother. He found a job in 1920 at the Freihofer Baking Company where he worked nights for the next four years. Under these circumstances Leon continued to develop his skills in drawing and painting and learned of the revolutionary developments in art that were taking place in Paris.

During the day he was granted permission to study anatomy at the Philadelphia School of Osteopathy where he dissected a cadaver and perfected his knowledge of the human figure. He also met and studied etching with Earl Horter, a well known illustrator, who had amassed a significant collection of modern art which included work by Brancusi, Matisse, and Cubist works by Picasso and Braque. Among the artists around Horter was Arthur Carles, a charismatic and controversial painter who taught at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Leon enrolled in the Academy in 1922, becoming what Carles described as, "his best student".

In the next three years Leon work ranged from academic studies of plaster casts, to pointillism, to landscapes of Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, as well as a series of pastels showing influences from Matisse to Picasso. Clearly influenced by Earl Horter's collection and Arthur Carles he mastered analytical cubism in works such as The Three Pears, 1923 and 1925 experimented with Purism in Moon Behind the Italian House. In 1925 Kelly was awarded a Cresson Scholarship and on June 14 he left for Europe.

Paris

The first trip to Europe lasted for approximately three and a half months and introduced Kelly to a culture and place where he felt he belonged. Though he returned to the Academy in the Fall, he left for Europe again a few months later to begin a four-year stay in Paris. He moved into an apartment at 19 rue Daguerre in Paris and began an existence intellectually rich but in creature comforts, very poor. "I kept a cinderblock over the drain in the kitchen sink to keep the rats out of the apartment" he once explained. He frequented the cafes making acquaintances with Henry Miller, James Joyce and the critic Félix Fénéon as well as others. His days were split between copying old master paintings in the Louvre and pursuing modernist ideas that were swirling through the work of all the artists around him. The Lake, 1926 and Interior of the Studio, 1927, now in the Newark Museum.

Patrons during this time were the police official Leon Zamaran, a collector of Courbets, Lautrecs and others, who began collecting Kelly's work. Another was Alfred Barnes of the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia.

In 1929 Kelly married a young French woman, Henriette D'Erfurth. She appears frequently in paintings and drawings done between 1928 and the early 1930s.

Philadelphia

The stock market crash of 1929 made it impossible to continue living in Paris and Kelly and Henriette returned to Philadelphia in 1930. He rented a studio on Thompson Street and began working and participating in shows in the city's galleries. Work from 1930 to 1940 showed continuing influences and experimentation with the themes and techniques acquired in Paris as well as a brief foray into Social Realism. The Little Gallery of Contemporary Art purchased the Absinthe Drinker...

Category

1920s Abstract Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Pastel

$4,000

Untitled Abstraction

By Medard P. Klein

Located in Fairlawn, OH

Untitled Abstraction

Graphite on paper. c. 1946

Unsigned

Provenance: Estate of the Artist

Inherited by his neighbor/caregiver

Condition: Staining at corners

...

Category

1940s Abstract Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Graphite

You May Also Like

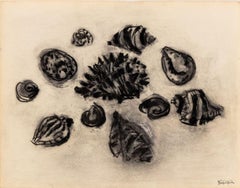

Still Life of Seashells

By Manfred Schwartz

Located in Astoria, NY

Manfred Schwartz (American, b. Poland, 1909-1970), Still Life of Seashells, Charcoal on Paper, with the artist's signature stamped lower right, unframed. 20" H x 25.75" W. Provenance...

Category

Mid-20th Century Modern Still-life Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Paper, Charcoal

Still Life of Seashells

By Manfred Schwartz

Located in Astoria, NY

Manfred Schwartz (American, b. Poland, 1909-1970), Still Life of Seashells, Charcoal on Paper, with the artist's signature stamped lower right, unframed. 20" H x 25.75" W. Provenance...

Category

Mid-20th Century Modern Still-life Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Paper, Charcoal

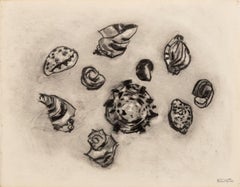

Still Life of Seashells

By Manfred Schwartz

Located in Astoria, NY

Manfred Schwartz (American, b. Poland, 1909-1970), Still Life of Seashells, Charcoal on Paper, with the artist's signature stamped lower right, unframed. 20" H x 25.75" W. Provenance...

Category

Mid-20th Century Modern Still-life Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Paper, Charcoal

Still Life of Seashells

By Manfred Schwartz

Located in Astoria, NY

Manfred Schwartz (American, b. Poland, 1909-1970), Still Life of Seashells, Charcoal on Paper, with the artist's signature stamped lower right, unframed. 20" H x 25.5" W. Provenance:...

Category

Mid-20th Century Modern Still-life Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Paper, Charcoal

Still Life - Drawing By Reynold Arnould - Mid-20th Century

Located in Roma, IT

Still Life is a Pencil Drawing realized by Reynold Arnould (Le Havre 1919 - Parigi 1980) in 1970.

Good condition included a white cardboard passpartout (50x35 cm).

Monogrammed by ...

Category

Mid-20th Century Modern Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Paper, Pencil

(Abstract Still Life) Untitled, 1964, Ian Hornak — Painting

By Ian Hornak

Located in Fairfield, CT

Artist: Ian Hornak (1944-2002)

Title: (Abstract Still Life) Untitled

Year: circa 1964

Medium: Acrylic on illustration board

Size: 10 x 9 inches

Condition: Good

Provenance: Estate of ...

Category

1960s Photorealist Nude Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Watercolor, Archival Paper

$2,600 Sale Price

20% Off

More Ways To Browse

Still Life Painting Of Shells

In The Manner Of Picasso

Still Life Painting 1940

Spiritual Abstract

Vintage Bear Painting

Paintings Of Shells

Shell Still Life Paintings

Agnes Pelton

Nicholas Roerich

Prints Signed By Artist

Antique Prints Engraving

1959 Painting

Contemporary Art On Paper

Bird Paintings

Dance Photography

Catalogue Raisonne

Signed David

Oil Painting By Artist Fields