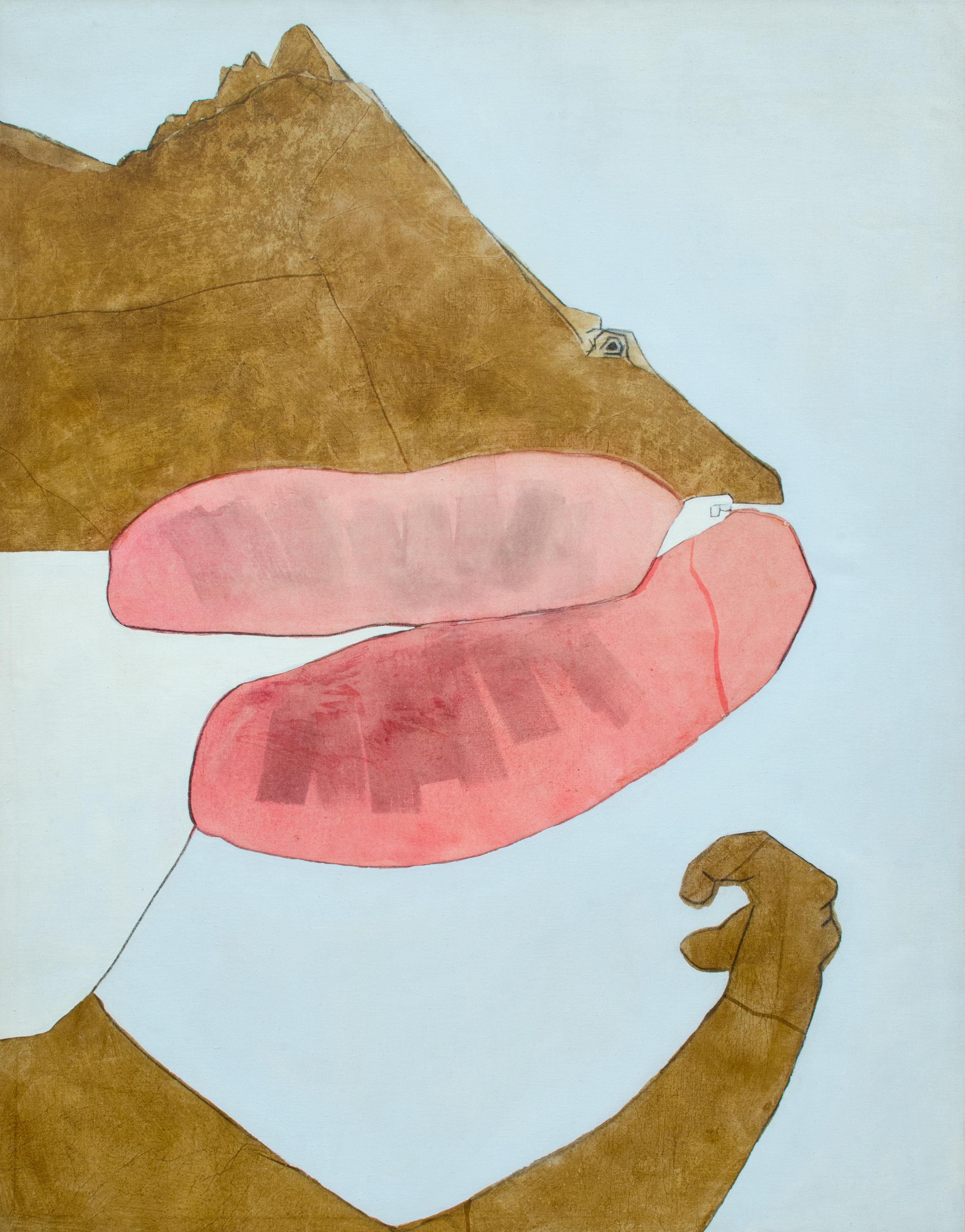

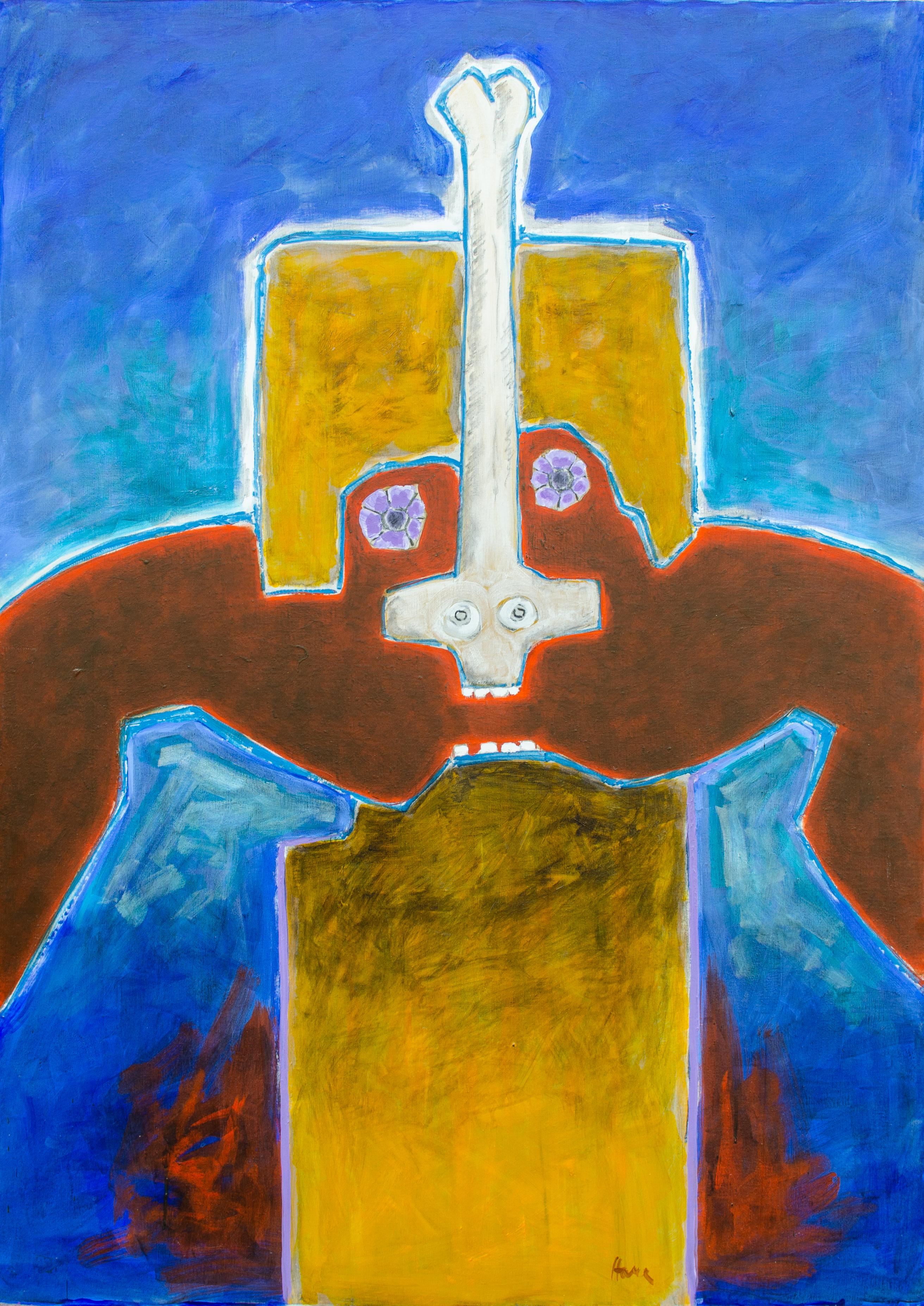

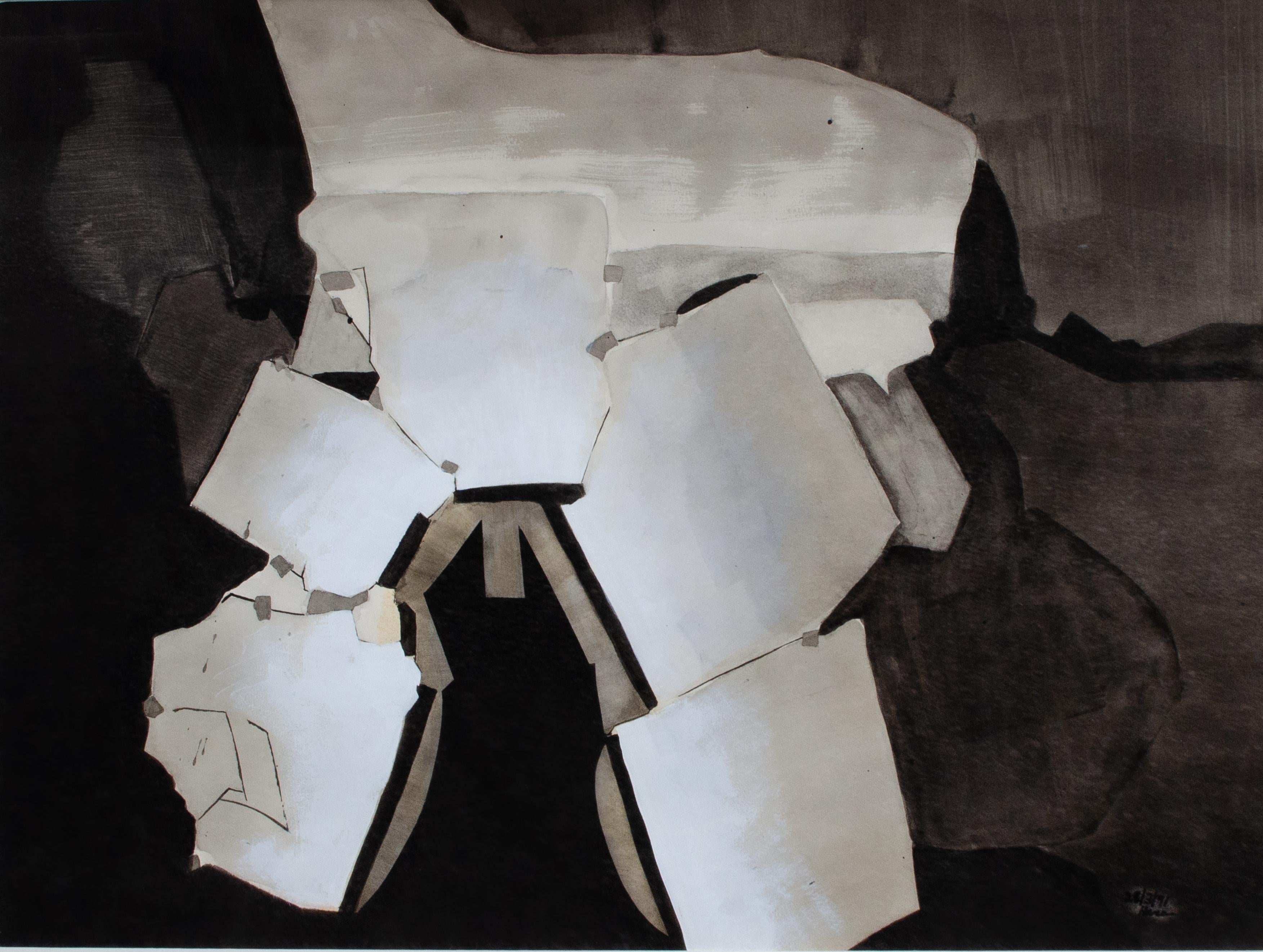

David Hare

Cronus Dining, 1968

Graphite, acrylic, paper collage on board

44 x 34 inches

“Freedom is what we want,” David Hare boldly stated in 1965, but then he added the caveat, “and what we are most afraid of.” No one could accuse David Hare of possessing such fear. Blithely unconcerned with the critics’ judgments, Hare flitted through most of the major art developments of the mid-twentieth century in the United States. He changed mediums several times; just when his fame as a sculptor had reached its apogee about 1960, he switched over to painting. Yet he remained attached to surrealism long after it had fallen out of official favor. “I can’t change what I do in order to fit what would make me popular,” he said. “Not because of moral reasons, but just because I can’t do it; I’m not interested in it.”

Hare was born in New York City in 1917; his family was both wealthy and familiar with the world of modern art. Meredith (1870-1932), his father, was a prominent corporate attorney. His mother, Elizabeth Sage Goodwin (1878-1948) was an art collector, a financial backer of the 1913 Armory Show, and a friend of artists such as Constantin Brancusi, Walt Kuhn, and Marcel Duchamp.

In the 1920s, the entire family moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico and later to Colorado Springs, in the hope that the change in altitude and climate would help to heal Meredith’s tuberculosis. In Colorado Springs, Elizabeth founded the Fountain Valley School where David attended high school after his father died in 1932. In the western United States, Hare developed a fascination for kachina dolls and other aspects of Native American culture that would become a recurring source of inspiration in his career.

After high school, Hare briefly attended Bard College (1936-37) in Annandale-on-Hudson. At a loss as to what to do next, he parlayed his mother’s contacts into opening a commercial photography studio and began dabbling in color photography, still a rarity at the time [Kodachrome was introduced in 1935]. At age 22, Hare had his first solo exhibition at Walker Gallery in New York City; his 30 color photographs included one of President Franklin Roosevelt.

As a photographer, Hare experimented with an automatist technique called “heatage” (or “melted negatives”) in which he heated the negative in order to distort the image. Hare described them as “antagonisms of matter.” The final products were usually abstractions tending towards surrealism and similar to processes used by Man Ray, Raoul Ubac, and Wolfgang Paalen.

In 1940, Hare moved to Roxbury, CT, where he fraternized with neighboring artists such as Alexander Calder and Arshile Gorky, as well as Yves Tanguy who was married to Hare’s cousin Kay Sage, and the art dealer Julian Levy. The same year, Hare received a commission from the American Museum of Natural History to document the Pueblo Indians. He traveled to Santa Fe and, for several months, he took portrait photographs of members of the Hopi, Navajo, and Zuni tribes that were published in book form in 1941.

World War II turned Hare’s life upside down. He became a conduit in the exchange of artistic and intellectual ideas between U.S. artists and the surrealist émigrés fleeing Europe. In 1942, Hare befriended Andre Breton, the principal theorist of surrealism. When Breton wanted to publish a magazine to promote the movement in the United States, he could not serve as an editor because he was a foreign national. Instead, Breton selected Hare to edit the journal, entitled VVV [shorth for “Victory, Victory, Victory”], which ran for four issues (the second and third issues were printed as a single volume) from June 1942 to February 1944. Each edition of VVV focused on “poetry, plastic arts, anthropology, sociology, (and) psychology,” and was extensively illustrated by surrealist artists including Giorgio de Chirico, Roberto Matta, and Yves Tanguy; Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp served as editorial advisors.

At the suggestion of Jacqueline Lamba, Andre Breton’s wife (soon to divorce Breton and marry Hare in 1946), Hare took up sculpture. His first sculptures were inspired by Alexander Calder and were made using wire frames that he covered with clay or plaster. In many cases, Hare combined human, animal, and mechanical forms to create peculiar hybrid creatures. His symbolically complex arrangements of abstract forms quickly made him one of the most famous sculptors of his generation. He exhibited at leading galleries for modern art such as the Julian Levy Gallery, Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century, the Samuel Kootz Gallery, and Galerie Maeght in Paris. Peggy Guggenheim called him “the best sculptor since Giacometti, Calder, and Moore.” A review in The New Yorker in 1951 praised Hare as “one of the moderns who refuse to accept the traditional limits of sculpture.”

When World War II ended, most of the exiled surrealists returned to Paris and tried unsuccessfully to revive the movement in Europe. In the years following the war, Hare often moved between New York and Paris, and continued to mix with influential artists and thinkers including Arshile Gorky, Jean-Paul Sartre, Balthus, Isamu Noguchi, Mark Rothko, and Pablo Picasso.

Meanwhile, Hare joined Barnett Newman, William Baziotes, Mark Rothko, and Robert Motherwell to found the Subjects of the Artist School at 35 East 8th Street in October 1948. The short-lived school hoped to promote avant-garde art through lectures by artists such as Jean Arp, John Cage, and Ad Reinhardt, but the school failed financially and closed in 1949.

Despite the failure of the school, Hare acquired an international reputation as a member of the generation of artists in the 1950s known as the New York School. Hare’s sculptures from the heyday of abstract expressionism were somewhat different in focus than his works of the late 1940s. Steel and bronze became his preferred materials and he began combining castoff metal objects such as old shovels, sections of pipe, and rusty tools into imaginative forms that seemed to spring from dreams and memories. With steel rods, he sketched ambiguous sunrises and sunsets in the air, capturing the cycles of the day in works known as ‘skyscapes.’ However, even in this period, he refused to come under the spell of absolute abstraction. “I prefer the figurative,” he said in 1968, “because I’m more interested in art as an adjunct to life than as a thing existing on its own.” He consistently believed that art should have some relation to the physical world.

In the early 1960s, at the height of his renown as a sculptor, the ever-restless Hare took the unusual step of switching to painting. “It wasn’t that I lost interest in sculpture,” he later said, but I got tired of being limited to an object.” The time-consuming aspects of welding and casting sculpture frustrated him. “There are things,” he said, “that you absolutely cannot express in three dimensions.” Painting was much quicker and a medium, and well-matched to keep up with the constant flow of Hare’s ideas.

Hare’s choice of subjects for his paintings was surprising. In the 1960s and 1970s, he often painted the sort of mythological and legendary subjects—such as Leda and the Swan--that interested surrealists because they seemed to provide a window to universal consciousness. He maintained these interests for more than 15 years, even when much of the art world had gone in other directions and surrealism was dismissed as outdated elitist figurative art permeated with “literary” narratives.

Hare was especially fascinated by the Greek myth of Cronus, the Titan who castrated and dethroned his father, Uranus. Cronus was also told that one of his children would kill him, so he tried to eat all of them. However, Zeus escaped, grew up, and ultimately did overthrow Cronus and imprisoned him.

Hare admitted that, “Of course I take my own liberties with this myth.” He later said that the myth was simply “a jumping off place…a symbol of growth through time.” For almost a decade, Hare obsessed over Cronus, whom he described as “part man, part earth, part time.” The culmination of that work was a solo exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in 1977 consisting of 18 paintings (many on a large scale), 10 drawings, and 5 sculptures that evoked Cronus.

After the Guggenheim show, Hare retreated from the public eye. He moved from his New York studio and spent a great deal of time in Idaho, where he moved permanently in 1986. He continued to paint and create sculptures until his death in 1992 in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, after an emergency operation for an aortic aneurysm.

David Hare was an experimenter, a searcher, and a risk taker with an eclectic and restless imagination. Although he worked in a variety of media, he is best known in the twenty-first century for his welded-metal abstract sculptures. For example, in 2020, his sculpture “Figure in the Windows” [1955] sold for $75,000 at auction. His paintings, however, remain under-appreciated and appear ripe for reassessment.