Items Similar to Paris L' Opera Le Plafond Romeo and Juliet Place de la Concorde Lt Ed Lithograph

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 8

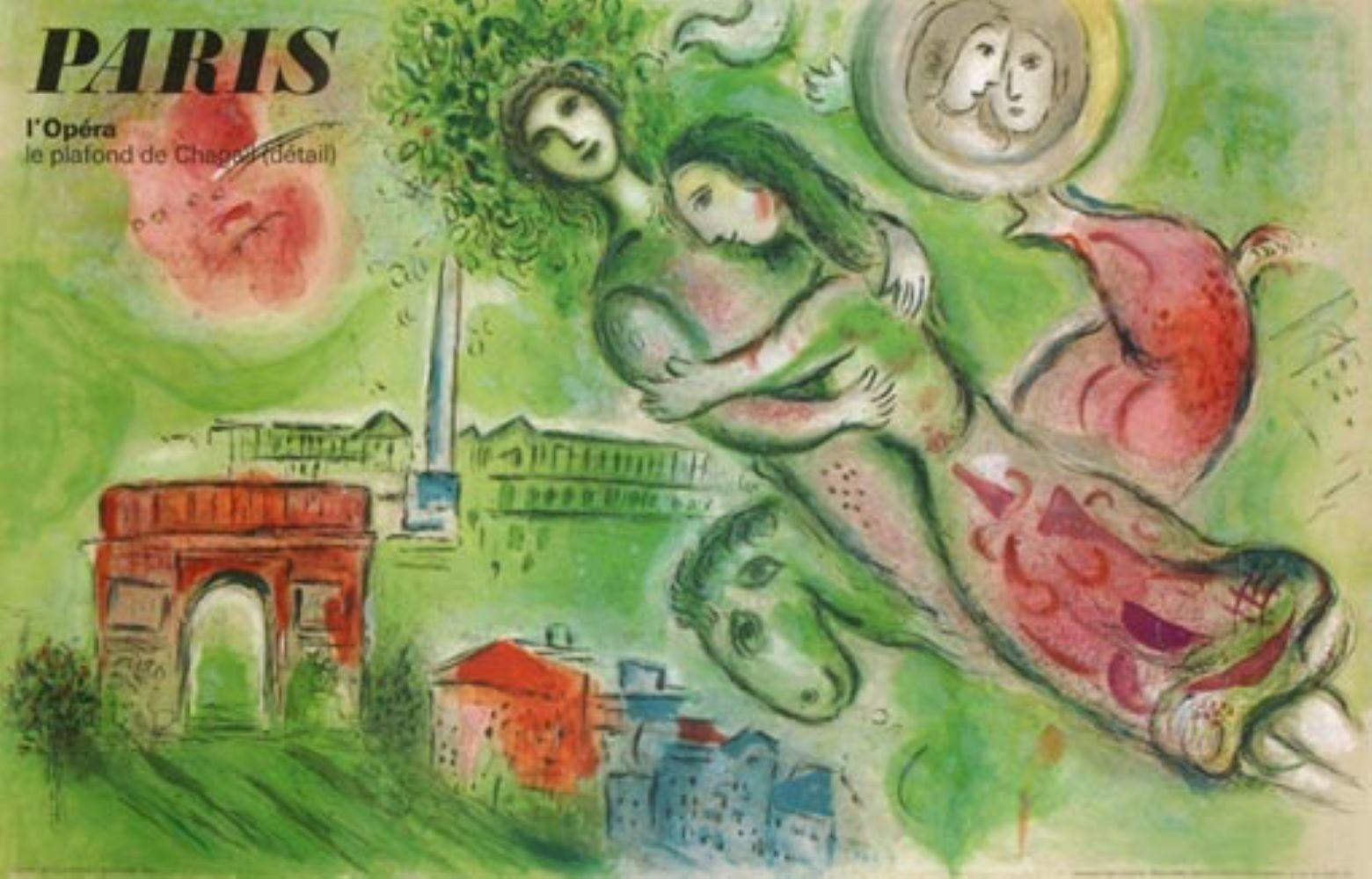

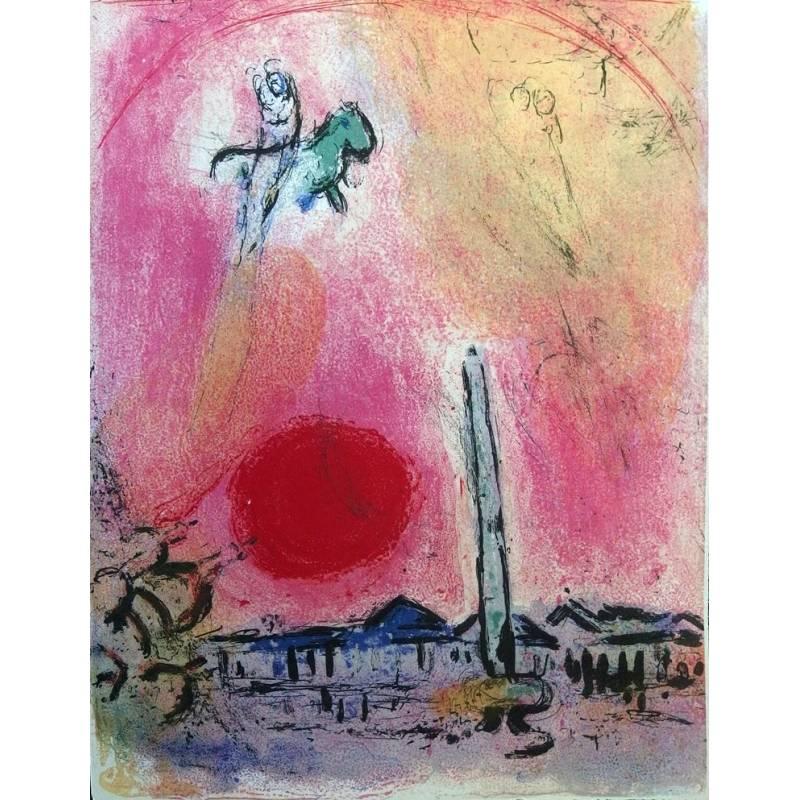

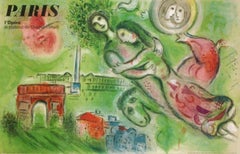

Paris L' Opera Le Plafond Romeo and Juliet Place de la Concorde Lt Ed Lithograph1965

1965

$2,000

£1,540.94

€1,760.24

CA$2,863.35

A$3,123.06

CHF 1,642.08

MX$37,478.08

NOK 20,732.99

SEK 19,338.22

DKK 13,146.40

About the Item

Marc Chagall

Paris L' Opera Le Plafond, Romeo and Juliet at Place de la Concorde and Arc de Triomphe, 1965

Original poster on wove paper

Unsigned

Limited Edition of 5000

24 3/4 × 38 3/4 inches

Unframed

Rare original and highly desirable poster, printed by prestigious Mourlot and published by the French tourist Bureau, Paris. Limited edition of only 5000 (unnumbered). This is the original with publishers' copyright and text - not a reprint.

Published by and for the French Government; printed by Mourlot.

A beautifully printed tribute to Hector Berlioz for Roméo et Juliette, from Chagall's ceiling for the Paris Opera. Also included is Chagall's rendering of the Place de la Concorde and the Arc de Triomphe. Sorlier 96.

Published by the French Tourist Bureau, Paris printed by Mourlot, Paris, France and Commissioned by the Government of France

More about Marc Chagall:

The eldest of nine children, Marc Chagall was born Moyshe Segal, in July 1887, in an area of the Russian Empire that’s today part of Belarus. His father, Zachar, hauled barrels for a herring merchant. Although Chagall was exaggerating in his memoir, My Life, when he compared Zachar to a ‘galley slave’, the work was apparently so hard that it made him determined to avoid a similar fate, and to pursue his dream of becoming an artist. ‘My heart used to twist like a Turkish bagel as I saw my father lift those weights,’ Chagall wrote.

In 1906, aged 19, Chagall moved to what was then the Russian capital, St Petersburg, where he attended art school. His home town became the main source of inspiration for his paintings at this time — as it would be throughout his career, even though he spent most of his life in faraway places. It’s often said that revisiting Vitebsk on canvas offered Chagall a nostalgic retreat into childhood, no matter how harsh the realities of his adult life (one marked, at different times, by war, revolution and flight).

The bearded man, attired in the long, dark coat and kashket (cap) typically worn by the poor Jewish communities in Vitebsk, is a recurrent presence in his paintings, paying tribute to the artist’s homeland and the culture that shaped him.

Chagall’s originality lay in his very personal synthesis of the influences he seized on from all sides. As well as Russian folk art and Orthodox church icons, he drew on Jewish artistic tradition, too — not to mention contemporary Western work, after he moved to Paris in 1911.

The subdued palette of his earlier paintings gave way to strong, pure colours inspired by the Fauves. Used for emotional and/or mystical effect, intense colour became a feature of Chagall’s art thereafter.

Upon moving to Paris, the artist changed his name to the French-sounding Marc Chagall. Paris was also where he met Pablo Picasso. Never one to lavish praise on a rival unduly, the Spaniard said of the Russian, ‘I don’t know where he gets those images from; he must have an angel in his head.’

For a while, Chagall dabbled with Cubism, but this was a short-lived phase — he found it too rational and geometric, commenting that he didn’t care for its ‘fill of square pears on triangular tables’.

In later life, from the 1950s onwards, he and Picasso would live near each other on the French Riviera. Chagall cherished his adopted home for the phenomenon he called lumière-liberté, or the ‘light of freedom’, and nowhere was this more intensely felt than in the south of France, where he always kept vases of flowers in his studio. The artist celebrated lumière-liberté as a joyous renewal of creative possibilities in a series of sumptuous floral paintings, and flowers were a subject to which he repeatedly returned.

Chagall returned to Russia to see his family and fiancée Bella in 1914. He planned to stay just three months, but the outbreak of World War I meant he had to postpone his return to Western Europe indefinitely. In 1917 the Bolshevik Revolution took place, and Chagall was sympathetic to it.

He was now, finally, granted full citizenship rights in his own country — something which, as a Jew under the Tsarist regime, he had been denied. He was even appointed Commissar for Art in Vitebsk, although ideological differences soon led to his resignation. Chagall’s work had taken an increasingly fantastical turn by this point, full of green cows and flying horses, and his opponents complained this had little to do with Marx or Lenin.

Back in Paris, in 1923 Surrealism had become the major intellectual movement in the city, and Chagall’s dreamlike visions from the previous decade were hailed as groundbreaking. According to the Surrealists’ leader, André Breton, ‘no work was ever so resolutely magical’ as Chagall’s. The Russian was officially invited to join the movement, but declined.

Levitating lovers are probably the most frequently repeated characters in Chagall’s oeuvre. From 1937 onwards, however, he also began to depict the Crucifixion on a regular basis. The date is no coincidence. Nazi deportations of and atrocities against Jews were becoming ever more prevalent.

Chagall’s response was to appropriate the Crucifixion from Christian artistic tradition and reconsider its subject as a symbol of Jewish martyrdom instead (Jesus himself, of course, having been a Jew). Nazi barbarism was clearly the main source of inspiration, but Chagall was also drawing on his experience of anti-Jewish pogroms during his youth in Russia.

France under Vichy rule was a dangerous place for Jews to live, so Chagall and Bella (now his wife) accepted an invitation of sanctuary in the United States. The artistic highlights of his stay included set and costume designs for Léonide Massine’s ballet Aleko, which premiered to great acclaim in 1942. Bella died from a viral infection two years later. In memoriam, her image would recur — as lover or bride — in several of Chagall’s paintings until his own death in 1985.

Chagall received a retrospective at both New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Art Institute of Chicago before returning to France in 1948. His place as one the key figures of 20th-century art was assured. Chagall started experimenting in an array of new media: tapestry, pottery, mosaics and, most successfully, stained glass. His penchant for large areas of saturated colour made stained glass a logical choice. His most famous commission was the Peace Window, in celestial blue, for the UN Secretariat building in New York.

In 1967, aged 80, Chagall painted two gigantic murals for the lobby of New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, at Lincoln Center: The Sources of Music and The Triumph of Music, both measuring 30 ft by 36 ft. In glowing red and yellow, he paid homage to the great composers of the past, most prominently Mozart, who flies like an angel above the Manhattan skyline, embracing characters from his opera The Magic Flute.

Chagall continued to work right up his death in France in 1985, aged 97. Indeed, on the day he passed away, he had been discussing a maquette painting for a tapestry commissioned by the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. Buried alongside his second wife, Vava, in the artists’ town of Saint Paul de Vence in Provence, Marc Chagall was the last surviving master of European Modernism.

- Creation Year:1965

- Dimensions:Height: 24.75 in (62.87 cm)Width: 38.75 in (98.43 cm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- After:Marc Chagall (1887 - 1985, French)

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:New York, NY

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU1745216809362

About the Seller

5.0

Platinum Seller

Premium sellers with a 4.7+ rating and 24-hour response times

Established in 2007

1stDibs seller since 2022

465 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 2 hours

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: New York, NY

- Return Policy

More From This Seller

View AllLovers and Others (unique mid century modern painting) - double sided artwork

By Nahum Tschacbasov

Located in New York, NY

Nahum Tschacbasov

Lovers and Others (Two Unique Works), 1978-1979

Gouache on Two-sided Paper (Two Signed Works)

Hand signed twice: once on each side

11 × 15 inches (each side)

A rare...

Category

Mid-20th Century Surrealist Abstract Paintings

Materials

Ink, Gouache

Honor Thy Father and Thy Mother (The Fifth Commandment) Lithograph Signed/N

By Robert Kushner

Located in New York, NY

Robert Kushner

Honor Thy Father and Thy Mother (The Fifth Commandment), 1987

6 Color Lithograph on Dieu Donne handmade paper

24 × 18 inches

Pencil signed and numbered 6/84 in graphite on the front

Unframed with deckled edges

This five color lithograph on Dieu Donne hand made paper with deckled edges is pencil signed, dated and numbered from the limited edition of 84. This 1980s Robert Kushner print was created as part of the 1987 portfolio "The Ten Commandments", in which ten top Jewish American artists were each invited to choose an Old Testament commandment to interpret in contemporary lithographic form. The "Chosen" artists were, in order of Commandment: Kenny Scharf, Joseph Nechvatal, Gretchen Bender, April Gornik, Robert Kushner, Nancy Spero, Vito Acconci, Jane Dickson, Judy Rifka and Richard Bosman. This is the first time the print will have been removed from the original portfolio case. (shown). Lisa Liebmann, who wrote the introduction to the collection, observed: "...The image has, for most of us, replaced the word..." With respect to the present work, she writes, "There is a sweet smell of nostalgia to Robert Kushner's view of the FIFTH COMMANDMENT, to honor one's parents. Kushner's subtly ornate use of colors suffuses his subject with a filagreed texture of warmth. In this gentle icon, the traditional duo - all those Ozzies and Harriets in our hearts and on the airwaves -are frames as if by a bubble bath of affection."

ROBERT KUSHNER BIOGRAPHY

Since participating in the early years of the Pattern and Decoration Movement in the 1970s, Robert Kushner has continued to address controversial issues involving decoration. Kushner draws from a unique range of influences, including Islamic and European textiles, Henri Matisse, Georgia O’Keeffe, Charles Demuth, Pierre Bonnard, Tawaraya Sotatsu, Ito Jakuchu, Qi Baishi, and Wu...

Category

1980s Contemporary Figurative Prints

Materials

Lithograph

Paradise, Garden of Eden, Lithograph on paper, Signed, titled #36/100, Unframed

Located in New York, NY

Helen Siegl

Paradise, 1976

Lithograph on wove paper

Pencil signed, dated and numbered 36/100

Unframed

Provenance: Rodger LaPelle Galleries, PA

depicts a scene reminiscent of the Gard...

Category

1970s Romantic Figurative Prints

Materials

Lithograph

Window on Another Dimension, signed/n lithograph by Picasso's famous mistress

By Françoise Gilot

Located in New York, NY

Françoise Gilot

Window on Another Dimension, 1981

Lithograph on Arches mould made Johannot paper

Signed and numbered in graphite pencil; also bears artist's monogram with date, edition of 60

Unframed

27.25 inches by 19.75 inches

Francoise Gilot was not just Picasso's muse; she was an accomplished artist in her own right, and at age 100, the New York Times dubbed her the art world's latest "It Girl".! Signed and numbered in graphite pencil; also bears artist's personal monograph with date. Held in original vintage frame under plexiglass. Charmingly, there is a sticker label on the back of the frame, from the "Picasso Gallery Custom Framing" in D.C.

This silkscreen is based upon Gilot's eponymous painting, also done in 1981

Excerpt from Alan Riding's 2023 New York Times obituary on Gilot:

" Françoise Gilot, an accomplished painter whose art was eclipsed by her long and stormy romantic relationship with a much older Pablo Picasso, and who alone among his many mistresses walked out on him, died on Tuesday at a hospital in Manhattan. She was 101...But unlike his two wives and other mistresses, Ms. Gilot rebuilt her life after she ended the relationship, in 1953, almost a decade after it had begun despite an age difference of 40 years. She continued painting and exhibiting her work and wrote books. In 1970, she married Jonas Salk, the American medical researcher who developed the first safe polio vaccine, and lived part of the time in California. Still, it was for her romance with Picasso that the public knew her best, particularly after her memoir, “Life with Picasso,” written with Carlton Lake, was published in 1964. It became an international best seller, and so infuriated Picasso that he broke off all contact with Ms. Gilot and their two children, Claude and Paloma Picasso. Ms. Gilot’s frank and often-sympathetic account of their relationship — she dedicated the book “to Pablo” — provided much of the material for the 1996 Merchant-Ivory movie, “Surviving Picasso,” in which she was played by Natascha McElhone, with Anthony Hopkins as Picasso.

If Ms. Gilot’s book sold well, so has her art. With her work in more than a dozen museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, her paintings fetched increasingly higher prices well into her later years.

As recently as June 2021, her painting “Paloma à la Guitare” (1965), a blue-toned portrait of her daughter, sold for $1.3 million in an online auction by Sotheby’s. That surpassed her previous record price, $695,000, paid for “Étude bleue,” a 1953 portrait of a seated woman, at a Sotheby’s auction in 2014.. And in November 2021, her abstract 1977 canvas “Living Forest” sold for $1.3 million as part of a retrospective of her work at Christie’s in Hong Kong. Lisa Stevenson, the head of curated sales for Sotheby’s in London, told ARTnews after the 2021 auction, “It isn’t commonly known that Gilot’s commitment to art was present long before her relationship with Pablo Picasso, and she was sadly often left in his shadow.”..

Marie Françoise Gilot was born into a prosperous family on Nov. 26, 1921, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris, the only child of Emile Gilot, an agronomist and chemical manufacturer, and Madeleine Renoult-Gilot. Her 19th-century ancestors had owned a couturier house of fashion whose clientele included Eugenia, the wife of Emperor Napoleon III. Marie Françoise was drawn to art from an early age, tutored by her mother, who had studied art history, ceramics and watercolor painting. Her father, however — recalled by Ms. Gilot as an authoritarian who had forced her to write with her right hand, though she was left-handed — had other ideas. Envisioning a career in science or the law for his daughter, he persuaded her to enroll at the University of Paris, where she received her bachelor’s degree in 1938 at age 17. She went on to study at the Sorbonne and the British Institute in Paris and receive a degree in English literature from Cambridge University. As war crept closer to France in 1939, her father sent her to the city of Rennes, northwest of Paris, to enroll in law school. All the while she continued working on her paintings. Then came the German occupation of Paris, in June 1940, and she joined other students in an anti-German protest march at the Arc de Triomphe. In a clash with the French and German authorities, Ms. Gilot was arrested, briefly detained and put under watch. “From day one, we were not the kind of people who would become collaborators,” she said of her family.

She continued her law studies at the University of Paris, but after taking her second-year examinations, in June 1941, she lost interest and abandoned the field, deciding to devote herself to art. She began private lessons with a fugitive Hungarian Jewish painter, Endre Rozsda...

Category

1980s Modern Abstract Prints

Materials

Lithograph

Metropolitan Opera Centennial 1883-1983 lithographic poster A Heart at the Opera

By Jim Dine

Located in New York, NY

Jim Dine

Metropolitan Opera Centennial 1883-1983 poster, 1983

Offset lithograph poster; unsigned

46 × 29 inches

Unframed

This limited edition poster was pu...

Category

1980s Pop Art Figurative Prints

Materials

Lithograph, Offset

Study for Bull and Condor, unique Ink on gouache signed, segy collection, framed

By Jacques Lipchitz

Located in New York, NY

JACQUES LIPCHITZ

Study for Bull and Condor, 1964

Original Ink on gouache on Paper drawing

and signed lower left front

Unique

Held in the original vintage frame

This work is from th...

Category

1960s Abstract Expressionist Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Ink, Gouache

You May Also Like

PARIS OPERA VINTAGE FRENCH TRAVEL POSTER after Marc Chagall

By Marc Chagall

Located in Dubai, Dubai

PARIS OPERA ORIGINAL VINTAGE FRENCH TRAVEL POSTER

AFTER MARC CHAGALL

Marc Chagall (1887-1985) was a pioneering Russian-French artist, ...

Category

1960s Contemporary Figurative Prints

Materials

Lithograph

after Marc Chagall, Original Poster, Paris Opera, Romeo and Juliette, Love, 1964

By Marc Chagall

Located in SAINT-OUEN-SUR-SEINE, FR

Original Poster-Marc Chagall-Opera Paris-Romeo and Juliette-Love, 1964

A detail of the ceiling of the Opera Garnier painted by Marc Chagall is represented: Romeo and Juliet.

Additi...

Category

20th Century French Modern Posters

Materials

Paper

Marc Chagall Original Poster PARIS L'Opera Romeo and Juliette, 1964

By (after) Marc Chagall

Located in Oud-Turnhout, VAN

Original poster Marc Chagall PARIS L'Opera, Le plafond de Chagall (detail) Romeo & Juliette. Made in France, 1964. D'apres Marc Chagall - Ch. Sortier Gravure. Printed in Paris, Franc...

Category

Vintage 1960s French Modern Posters

Materials

Paper

$1,891 Sale Price

20% Off

Free Shipping

Marc Chagall, Place de la Concorde, from Verve, Revue Artistique, 1953

By Marc Chagall

Located in Southampton, NY

This exquisite lithograph by Marc Chagall (1887–1985), titled Place de la Concorde (Place de la Concorde), from Verve, Revue Artistique et Litteraire, Vol. VII, No. 27–28, originates...

Category

1950s Expressionist Landscape Prints

Materials

Lithograph

$1,436 Sale Price

20% Off

Free Shipping

Original Vintage Travel Poster Paris Opera Le Plafond De Chagall Romeo & Juliet

Located in London, GB

Original vintage travel advertising poster published by the French Government and the General Committee for Tourism to promote travel to Paris to visit the Opera Garnier and admire the Great Hall ceiling fresco...

Category

Vintage 1960s French Posters

Materials

Paper

Marc Chagall - La Place de la Concorde - Original Lithograph

By Marc Chagall

Located in Collonge Bellerive, Geneve, CH

Marc Chagall

Original Lithograph

Title: La Place de la Concorde

1963

Dimensions: 39 x 30 cm

Edition: 180

Unsigned as issued.

From Regards sur Paris

Reference: Catalogue Raisonné, Mou...

Category

1960s Surrealist Figurative Prints

Materials

Lithograph