Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 7

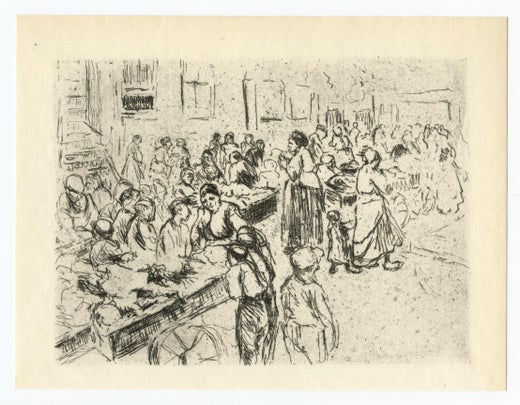

Max LiebermannHercules – Hindenburg Slays the Russian Bear / - Classical Impressionism -1914

1914

$1,083.77List Price

About the Item

- Creator:Max Liebermann (1847 - 1935, German)

- Creation Year:1914

- Dimensions:Height: 16.54 in (42 cm)Width: 11.82 in (30 cm)Depth: 0.4 in (1 cm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:Berlin, DE

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU2438216387132

Max Liebermann

Max Liebermann (Berlin, 1847 - 1935) was a German painter, graphic artist, pastelist and illustrator. A transition from realism to impressionism is visible in his work.

In 1871 he visited the studio of the Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy in Düsseldorf, whose work made a great impression on Liebermann. He then makes a short trip to the Netherlands. In December 1873 he went to Paris. He met Munkácsy, Troyon, Daubigny, Corot, Millet and Manet. In the Louvre he devoted himself to the study of the Dutch masters.

In 1920 he was appointed president of the Preußische Akademie der Künste. In 1933, Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany. Because of his Jewish background, Liebermann resigned as honorary president of the Preußische Akademie der Künste. He then joined the newly founded Kulturbund Deutscher Juden and gave financial support to young Jews who wanted to flee to Palestine. In the last years of his life, Liebermann was shunned by the German artist community.

Liebermann was active for more than sixty years and made about 1200 oil paintings. For years, Liebermann was called the "apostle of ugliness." Yet he was groundbreaking and avant-garde. The real impressionist work did not come until the end of 1900. In the Netherlands he was inspired by the wide landscapes, the sea and the beach.

About the Seller

5.0

Vetted Professional Seller

Every seller passes strict standards for authenticity and reliability

Established in 2014

1stDibs seller since 2023

21 sales on 1stDibs

Authenticity Guarantee

In the unlikely event there’s an issue with an item’s authenticity, contact us within 1 year for a full refund. DetailsMoney-Back Guarantee

If your item is not as described, is damaged in transit, or does not arrive, contact us within 7 days for a full refund. Details24-Hour Cancellation

You have a 24-hour grace period in which to reconsider your purchase, with no questions asked.Vetted Professional Sellers

Our world-class sellers must adhere to strict standards for service and quality, maintaining the integrity of our listings.Price-Match Guarantee

If you find that a seller listed the same item for a lower price elsewhere, we’ll match it.Trusted Global Delivery

Our best-in-class carrier network provides specialized shipping options worldwide, including custom delivery.You May Also Like

Nude Figure Posterior View, Figurative Drypoint Etching

By Jim Smyth

Located in Soquel, CA

Limited edition drypoint etching of a nude figure from a posterior view by Jim Smyth (American, b. 1938). Numbered and signed by hand "7/15 Jim Smyth" along the bottom edge. Presented in a new cream and off-white double mat. No frame. Image size: 14.75"H x 10.75"W

Jim Smyth (American, b. 1938) has studied at the Academia de Belle Arti in Fiorenza, Italy, Ecole des BeauxArts in Geneva, New York Academy and the Art Students league. He is also a graduate from UC Berkeley with a degree in Fine Art.

Although academically trained, Smyth practices and teaches a more impressionistic style of painting, focusing on Alla Prima technique. He is particularly knowledgeable about drawing, perspective, color theory and the human figure, his passion. Smyth, with an extensive academic knowledge, has a profound love of all human representations as illustrated by his humorous quick sketches from life. He also practices and teaches oil painting and pastels.

When not in Provence, or Southeastern France, Smyth teaches intensely in art schools, art centers and several colleges in the Bay Area. He is a beloved instructor and his classes fill in quickly as he is very knowledgeable.

On his return to the United States, he began studying with Mr. Alanson Appleton at the College of San Mateo, San Mateo, California. Smyth was a founding member of the Appletree Etchers, Inc., an etching print shop organized by Mr. Appleton and his students to develop and promote color intaglio. Smyth served as Master Printer at the studio for many years perfecting the techniques of intaglio and developing the color theories of Mr. Appleton as applied to the deep etched plate.

Smyth received his degree from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1972 and holds the California Community College Certificate and an Adult Education Certificate. Smyth was invited to teach "Anatomy for Artists" at Foothill College, Los Altos Hills, California, as a result of his many years of dissection of the cadaver and developed the course of study of Perspective for the college. During this period, he began teaching Life Drawing at the Pacific Art League of Palo Alto, Palo Alto, California. During the following thirty years Smyth has taught an average of twelve classes per week at the Pacific Art League of Palo Alto, the Palo Alto Art Center and the Burlingame Recreation Department among others in all phases of drawing and painting. He has conducted many workshops for the California Academy of Painters in many aspects of drawing and painting. Currently, he is an Adjunct Professor of Drawing at the College of San Mateo, San Mateo, California. He is an authority on the materials of painting and drawing, techniques of traditional drawing and painting, color theory, perspective and anatomy for artists. In his career in Life Drawing, Smyth has made over two hundred thousand drawings from the model.

In addition to studies at Berkeley, Smyth has studied at the College of San Mateo, Foothill College, De Anza College, Mission College and West Valley College, all in California. One of the pivotal points in his career was studying with Mr. Maynard Dixon Stewart at the University of San Jose, California. He spent a year at the New York Academy of Art where he was offered a full scholarship and at the Art Students League of New York. He concurrently attended classes at the National Academy of Design in New York. Among others, Smyth studied with M. Andrejivec, Ted Schmidt, Elliot Goldfinger, Gary Fagin, Ted Jacobs, Leo Neufeld, David Leffel, Jack Ferragasso, Jim Childs and Everett Raymond Kinstler and Kim English. Smyth has also studied with the noted painter and colorist, Ovanes Berberian. In 2002 Jim was invited to study at the Academy of Art in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he worked in Life Drawing and Life Painting.

Smyth is a popular lecturer, a sought after demonstrator and juror. He is the recipient of many awards for both his painting and his teaching. In 1988 and again in 2003, he received the Kenneth Washburn...

Category

Late 20th Century American Impressionist Figurative Prints

Materials

Paper, Ink, Drypoint

$700 Sale Price

20% Off

H 16 in W 12 in D 0.07 in

"Study 2", Seated Figure Lithograph

By Jim Smyth

Located in Soquel, CA

Beautiful nude figurative lithograph by Jim Smyth (American, b. 1938). Numbered, titled, signed and dated "8/12", "Study 2", "Smyth 75” along the bottom edge. Unframed.

Jim Smyth has studied at the Academia de Belle Arti in Fiorenza, Italy, Ecole des BeauxArts in Geneva, New York Academy, and the Art Students League. He is also a graduate of UC Berkeley with a degree in Fine Art.

Although academically trained, Smyth practices and teaches a more impressionistic style of painting, focusing on the Alla Prima technique.

He is particularly knowledgeable about drawing, perspective, color theory and the human figure, his passion. Smyth, with extensive academic knowledge, has a profound love of all human representations as illustrated by his humorous quick sketches from life. He also practices and teaches oil painting and pastels.

When not in Provence, or Southeastern France, Smyth teaches intensely in art schools, art centers and several colleges in the Bay Area. He is a beloved instructor and his classes fill in quickly as he is very knowledgeable.

On his return to the United States, he began studying with Mr. Alanson Appleton at the College of San Mateo, San Mateo, California. Smyth was a founding member of the Appletree Etchers, Inc., an etching print shop organized by Mr. Appleton and his students to develop and promote color intaglio. Smyth served as Master Printer at the studio for many years perfecting the techniques of intaglio and developing the color theories of Mr. Appleton as applied to the deeply etched plate.

Smyth received his degree from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1972 and holds the California Community College Certificate and an Adult Education Certificate. Smyth was invited to teach "Anatomy for Artists" at Foothill College, Los Altos Hills, California, as a result of his many years of dissection of the cadaver and developed the course of study of Perspective for the college. During this period, he began teaching Life Drawing at the Pacific Art League of Palo Alto, Palo Alto, California. During the following thirty years Smyth has taught an average of twelve classes per week at the Pacific Art League of Palo Alto, the Palo Alto Art Center and the Burlingame Recreation Department among others in all phases of drawing and painting. He has conducted many workshops for the California Academy of Painters in many aspects of drawing and painting. Currently, he is an Adjunct Professor of Drawing at the College of San Mateo, San Mateo, California. He is an authority on the materials of painting and drawing, techniques of traditional drawing and painting, color theory, perspective and anatomy for artists. In his career in Life Drawing, Smyth has made over two hundred thousand drawings from the model.

In addition to studies at Berkeley, Smyth has studied at the College of San Mateo, Foothill College, De Anza College, Mission College, and West Valley College, all in California. One of the pivotal points in his career was studying with Mr. Maynard Dixon Stewart at the University of San Jose, California. He spent a year at the New York Academy of Art where he was offered a full scholarship and at the Art Students League of New York. He concurrently attended classes at the National Academy of Design in New York. Among others, Smyth studied with M. Andrejivec, Ted Schmidt, Elliot Goldfinger, Gary Fagin, Ted Jacobs, Leo Neufeld, David Leffel, Jack Ferragasso, Jim Childs and Everett Raymond Kinstler and Kim English. Smyth has also studied with the noted painter and colorist, Ovanes Berberian. In 2002 Jim was invited to study at the Academy of Art in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he worked in Life Drawing and Life Painting.

Smyth is a popular lecturer, a sought after demonstrator and juror. He is the recipient of many awards for both his painting and his teaching. In 1988 and again in 2003, he received the Kenneth Washburn...

Category

1970s American Impressionist Figurative Prints

Materials

Paper, Etching

"The Aunties" - Figurative Abstract Limited Edition Print, 20/100

By Anne Ormsby

Located in Soquel, CA

Beautiful figurative giclée and watercolor limited edition print titled "The Aunties", a homage to the classical figurative sculpture The Three Graces, by Anne Ormsby, a Aptos, Calif...

Category

1990s American Impressionist Figurative Prints

Materials

Paper, Watercolor, Giclée

$1,240 Sale Price

20% Off

H 52 in W 42 in D 3 in

"La Femme et la Folie Dominent le Monde II" - 1886 Print on Paper

By Félicien Rops

Located in Soquel, CA

"La Femme et la Folie Dominent le Monde II" - 1886 Print on Paper

("The Woman and the Madness Overlooking The World II")

1886 French illustration from Felicien Rops (Belgian, 1833-...

Category

1880s Impressionist Figurative Prints

Materials

Etching, Paper, Ink

$875

H 12 in W 9 in D 0.5 in

"Study 2" Figurative Lithograph

By Jim Smyth

Located in Soquel, CA

Nude figurative lithograph by Jim Smyth (American, b. 1938). Numbered, titled, signed and dated "5/12", "Study 2", "Smyth 74” along the bottom edge. Unframed.

Jim Smyth has studied at the Academia de Belle Arti in Fiorenza, Italy, Ecole des BeauxArts in Geneva, New York Academy, and the Art Students League. He is also a graduate of UC Berkeley with a degree in Fine Art.

Although academically trained, Smyth practices and teaches a more impressionistic style of painting, focusing on the Alla Prima technique.

He is particularly knowledgeable about drawing, perspective, color theory and the human figure, his passion. Smyth, with extensive academic knowledge, has a profound love of all human representations as illustrated by his humorous quick sketches from life. He also practices and teaches oil painting and pastels.

When not in Provence, or Southeastern France, Smyth teaches intensely in art schools, art centers and several colleges in the Bay Area. He is a beloved instructor and his classes fill in quickly as he is very knowledgeable.

On his return to the United States, he began studying with Mr. Alanson Appleton at the College of San Mateo, San Mateo, California. Smyth was a founding member of the Appletree Etchers, Inc., an etching print shop organized by Mr. Appleton and his students to develop and promote color intaglio. Smyth served as Master Printer at the studio for many years perfecting the techniques of intaglio and developing the color theories of Mr. Appleton as applied to the deeply etched plate.

Smyth received his degree from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1972 and holds the California Community College Certificate and an Adult Education Certificate. Smyth was invited to teach "Anatomy for Artists" at Foothill College, Los Altos Hills, California, as a result of his many years of dissection of the cadaver and developed the course of study of Perspective for the college. During this period, he began teaching Life Drawing at the Pacific Art League of Palo Alto, Palo Alto, California. During the following thirty years Smyth has taught an average of twelve classes per week at the Pacific Art League of Palo Alto, the Palo Alto Art Center and the Burlingame Recreation Department among others in all phases of drawing and painting. He has conducted many workshops for the California Academy of Painters in many aspects of drawing and painting. Currently, he is an Adjunct Professor of Drawing at the College of San Mateo, San Mateo, California. He is an authority on the materials of painting and drawing, techniques of traditional drawing and painting, color theory, perspective and anatomy for artists. In his career in Life Drawing, Smyth has made over two hundred thousand drawings from the model.

In addition to studies at Berkeley, Smyth has studied at the College of San Mateo, Foothill College, De Anza College, Mission College, and West Valley College, all in California. One of the pivotal points in his career was studying with Mr. Maynard Dixon Stewart at the University of San Jose, California. He spent a year at the New York Academy of Art where he was offered a full scholarship and at the Art Students League of New York. He concurrently attended classes at the National Academy of Design in New York. Among others, Smyth studied with M. Andrejivec, Ted Schmidt, Elliot Goldfinger, Gary Fagin, Ted Jacobs, Leo Neufeld, David Leffel, Jack Ferragasso, Jim Childs and Everett Raymond Kinstler and Kim English. Smyth has also studied with the noted painter and colorist, Ovanes Berberian...

Category

1970s American Impressionist Figurative Prints

Materials

Paper, Etching

"Study 6" Figurative Abstract Lithograph

By Jim Smyth

Located in Soquel, CA

Graceful abstract figurative lithograph by Jim Smyth (American, b. 1938). Numbered, titled, signed and dated "5/12", "Study 2", "Smyth 74” along the bottom edge. Unframed.

Jim Smyth has studied at the Academia de Belle Arti in Fiorenza, Italy, Ecole des BeauxArts in Geneva, New York Academy, and the Art Students League. He is also a graduate of UC Berkeley with a degree in Fine Art.

Although academically trained, Smyth practices and teaches a more impressionistic style of painting, focusing on the Alla Prima technique.

He is particularly knowledgeable about drawing, perspective, color theory and the human figure, his passion. Smyth, with extensive academic knowledge, has a profound love of all human representations as illustrated by his humorous quick sketches from life. He also practices and teaches oil painting and pastels.

When not in Provence, or Southeastern France, Smyth teaches intensely in art schools, art centers and several colleges in the Bay Area. He is a beloved instructor and his classes fill in quickly as he is very knowledgeable.

On his return to the United States, he began studying with Mr. Alanson Appleton at the College of San Mateo, San Mateo, California. Smyth was a founding member of the Appletree Etchers, Inc., an etching print shop organized by Mr. Appleton and his students to develop and promote color intaglio. Smyth served as Master Printer at the studio for many years perfecting the techniques of intaglio and developing the color theories of Mr. Appleton as applied to the deeply etched plate.

Smyth received his degree from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1972 and holds the California Community College Certificate and an Adult Education Certificate. Smyth was invited to teach "Anatomy for Artists" at Foothill College, Los Altos Hills, California, as a result of his many years of dissection of the cadaver and developed the course of study of Perspective for the college. During this period, he began teaching Life Drawing at the Pacific Art League of Palo Alto, Palo Alto, California. During the following thirty years Smyth has taught an average of twelve classes per week at the Pacific Art League of Palo Alto, the Palo Alto Art Center and the Burlingame Recreation Department among others in all phases of drawing and painting. He has conducted many workshops for the California Academy of Painters in many aspects of drawing and painting. Currently, he is an Adjunct Professor of Drawing at the College of San Mateo, San Mateo, California. He is an authority on the materials of painting and drawing, techniques of traditional drawing and painting, color theory, perspective and anatomy for artists. In his career in Life Drawing, Smyth has made over two hundred thousand drawings from the model.

In addition to studies at Berkeley, Smyth has studied at the College of San Mateo, Foothill College, De Anza College, Mission College, and West Valley College, all in California. One of the pivotal points in his career was studying with Mr. Maynard Dixon Stewart at the University of San Jose, California. He spent a year at the New York Academy of Art where he was offered a full scholarship and at the Art Students League of New York. He concurrently attended classes at the National Academy of Design in New York. Among others, Smyth studied with M. Andrejivec, Ted Schmidt, Elliot Goldfinger, Gary Fagin, Ted Jacobs, Leo Neufeld, David Leffel, Jack Ferragasso, Jim Childs and Everett Raymond Kinstler and Kim English. Smyth has also studied with the noted painter and colorist, Ovanes Berberian...

Category

1970s American Impressionist Figurative Prints

Materials

Paper, Etching

"Young Woman Washing" - Signed Framed Late 20th Century Nude Print

Located in New Orleans, LA

A lovely drawing by Cortland Butterfield, signed, in an edition of 200 (this one numbered 110). Professionally float-framed and ready to hang. He...

Category

Late 20th Century Impressionist Nude Prints

Materials

Paper

$296 Sale Price

25% Off

H 19 in W 16 in

Nude Woman - Vintage Offset Poster after P. A. Renoir - Mid-20th Century

By Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Located in Roma, IT

Nude Woman is an offset poster realized after Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

In good conditions except for some rips on the margin.

Signed on the lower right corner.

The artwork represent...

Category

Mid-20th Century Impressionist Figurative Prints

Materials

Paper, Offset

$216

H 15.16 in W 17.92 in D 0.04 in

Jean Gabriel Domergue - Happiness - Original Etching

By Jean-Gabriel Domergue

Located in Collonge Bellerive, Geneve, CH

Original Etching by Jean-Gabriel Domergue

Dimensions: 33 x 25 cm

1924

Edition of 100

This artwork is part of the famous portfolio The Afternoon of a F...

Category

1920s Impressionist Nude Prints

Materials

Lithograph

$1,445

H 15.75 in W 12.21 in D 0.04 in

Jean Gabriel Domergue - Lying Woman - Original Etching

By Jean-Gabriel Domergue

Located in Collonge Bellerive, Geneve, CH

Original Etching by Jean-Gabriel Domergue

Dimensions: 33 x 25 cm

1924

Edition of 100

This artwork is part of the famous portfolio The Afternoon of a Faun.

Jean-Gabriel Domergue

Jea...

Category

1920s Impressionist Nude Prints

Materials

Lithograph

$1,445

H 15.75 in W 12.21 in D 0.04 in

More From This Seller

View AllPutti in an allegorical love game / - The Ambivalence of Eros -

By Francesco Bartolozzi

Located in Berlin, DE

Francesco Bartolozzi (1728 Florence - 1815 Lisbon), Putti in an allegorical love game, around 1764. Crayon engraving on laid paper after a drawing by Guercino, 21 cm x 29 cm (plate s...

Category

1760s Realist Figurative Prints

Materials

Paper

Four Young Women and the Boy Cupid / - Mysterious Virtuosity -

By Francesco Bartolozzi

Located in Berlin, DE

Francesco Bartolozzi (1728 Florence - 1815 Lisbon), Mythological Scene with Four Young Women and the Boy Cupid, 1764. Crayon engraving on laid paper after a drawing by Guercino, 22 c...

Category

1760s Realist Figurative Prints

Materials

Paper

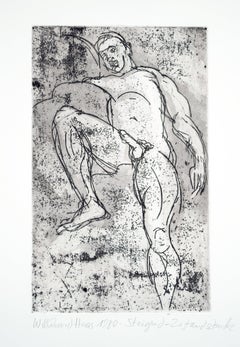

Rising

Located in Berlin, DE

Willibrord Haas (*1936 Schramberg), Rising, 1980. Etching, 35 cm x 22 cm (plate size), 53.5 cm x 38 cm (sheet size). Signed “Willibrord Haas” in pencil by the artist, dated “1980”, t...

Category

1980s Realist Nude Prints

Materials

Paper

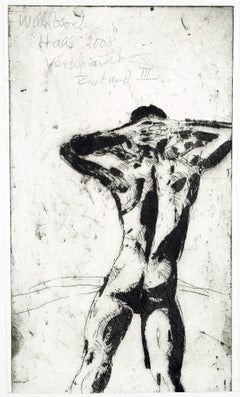

Entangled

Located in Berlin, DE

Willibrord Haas (*1936 Schramberg), Entangled, 2008. etching, 28 cm (height) x 17 cm (width). Signed “Willibrord Haas” in pencil by the artist, dated “2008”, titled “Verschränkt” and...

Category

Early 2000s Realist Nude Prints

Materials

Paper

Reproachful

Located in Berlin, DE

Willibrord Haas (*1936 Schramberg), Reproachful, 2010. etching, 33.5 cm x 20 cm (plate size), 54 cm x 37.5 cm (sheet size). Signed “Willibrord Haas” in lead by the artist, dated “201...

Category

2010s Realist Nude Prints

Materials

Paper

Kufi poses

Located in Berlin, DE

Willibrord Haas (*1936 Schramberg), Kufi poses, 2012. Etching, 44 cm x 32 cm (plate size), 54 cm x 37.5 cm (sheet size). Signed “Willibrord Haas” in lead by the artist, dated “2012”,...

Category

2010s Realist Nude Prints

Materials

Paper