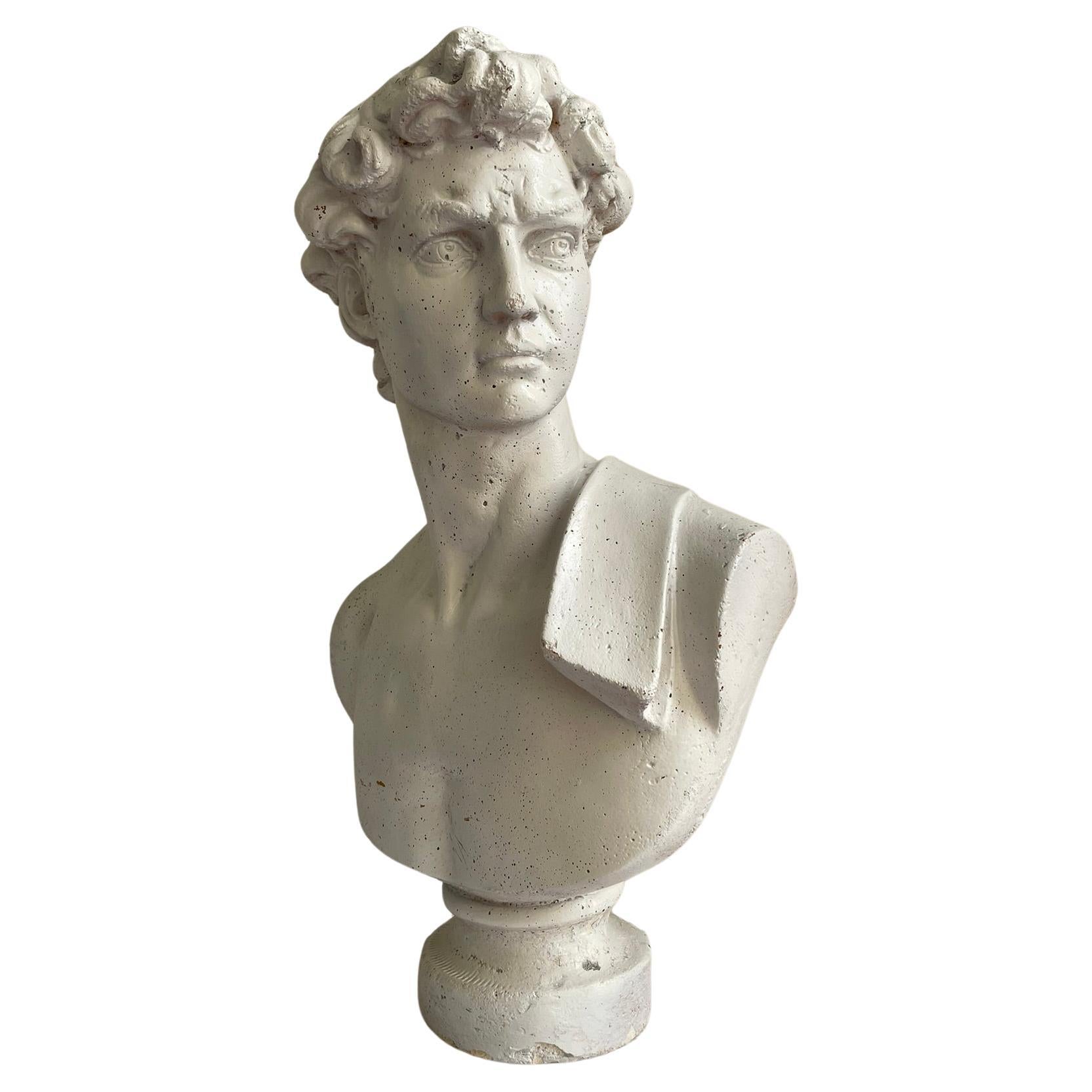

A large plaster buste of David after the model by Michelangelo, 1920's/1930's

View Similar Items

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 8

A large plaster buste of David after the model by Michelangelo, 1920's/1930's

$3,941.02List Price

About the Item

- Dimensions:Height: 48.04 in (122 cm)

- Materials and Techniques:

- Place of Origin:

- Period:

- Date of Manufacture:± 1920/1930

- Condition:Wear consistent with age and use. Minor damages at the base of the buste.

- Seller Location:Baambrugge, NL

- Reference Number:1stDibs: 1307259333228

About the Seller

5.0

Vetted Professional Seller

Every seller passes strict standards for authenticity and reliability

Established in 1967

1stDibs seller since 2012

138 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 20 hours

Authenticity Guarantee

In the unlikely event there’s an issue with an item’s authenticity, contact us within 1 year for a full refund. DetailsMoney-Back Guarantee

If your item is not as described, is damaged in transit, or does not arrive, contact us within 7 days for a full refund. Details24-Hour Cancellation

You have a 24-hour grace period in which to reconsider your purchase, with no questions asked.Vetted Professional Sellers

Our world-class sellers must adhere to strict standards for service and quality, maintaining the integrity of our listings.Price-Match Guarantee

If you find that a seller listed the same item for a lower price elsewhere, we’ll match it.Trusted Global Delivery

Our best-in-class carrier network provides specialized shipping options worldwide, including custom delivery.More From This Seller

View AllWhite Marble Bust of Hercules and the Nemean Lion - Late 20th Century

Located in Baambrugge, NL

This impressive white marble bust depicts the mythical figure of Hercules, shown holding the head of the Nemean Lion. A powerful example of sculptural art, dating from the late 20th ...

Category

Late 20th Century Italian Busts

Materials

Marble

Large Old Polychrome Painted Metal Model of a Lorry

Located in Baambrugge, NL

A large model of a lorry made in the second quarter of the 20th century. The cab is red, the body and flatbed maroon, above four spoked wheels. After an American Brockway truck.

...

Category

Vintage 1920s European Industrial Toys and Dolls

Materials

Metal

Midcentury White-Painted Italian Terracotta Sculpture of a Borzoi Hound, 1970s

Located in Baambrugge, NL

Vintage white-painted Italian terracotta sculpture of a Borzoi Hound, 1970s. This life-size terracotta sculpture of a stunning white Borzoi hound was crafted in Italy during the 1970...

Category

Mid-20th Century Italian Animal Sculptures

Materials

Terracotta

Grand Marble Bust of Omphale with Hercules' Lion Skin – Amsterdam, c. 1740

Located in Baambrugge, NL

This exceptional, larger-than-life bust is an impressive work in Carrara marble, crafted in Amsterdam around 1740. It depicts Omphale, the Lydian queen, identifiable by Hercules’ lio...

Category

Antique 1740s Dutch Busts

Materials

Marble

17th-century Dutch Bust of Mercury in White Carrara Marble

Located in Baambrugge, NL

This refined 17th-century bust of Mercury, masterfully sculpted from white Carrara marble, depicts the Roman god of commerce, travelers, and eloquence in timeless simplicity. His cha...

Category

Antique 17th Century Dutch Busts

Materials

Carrara Marble

Pair of Antique Brown Solid Marble Columns, Brocatelle Veining, Classical Style

Located in Baambrugge, NL

Elegant pair of solid marble columns in a soft, powdery brown tone with a brocatelle pattern and natural veining. Their warm coloring instantly conveys a luxurious and classical appe...

Category

Antique 19th Century Dutch Animal Sculptures

Materials

Marble

You May Also Like

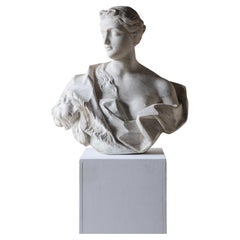

"David by Michelangelo" Plaster Bust

Located in Sacile, PN

A gorgeous white Plaster Bust of "David by Michelangelo".

This statue is based on the sculpture of David by Michelangelo, which is a masterpiece ...

Category

Late 20th Century Italian Neoclassical Busts

Materials

Plaster

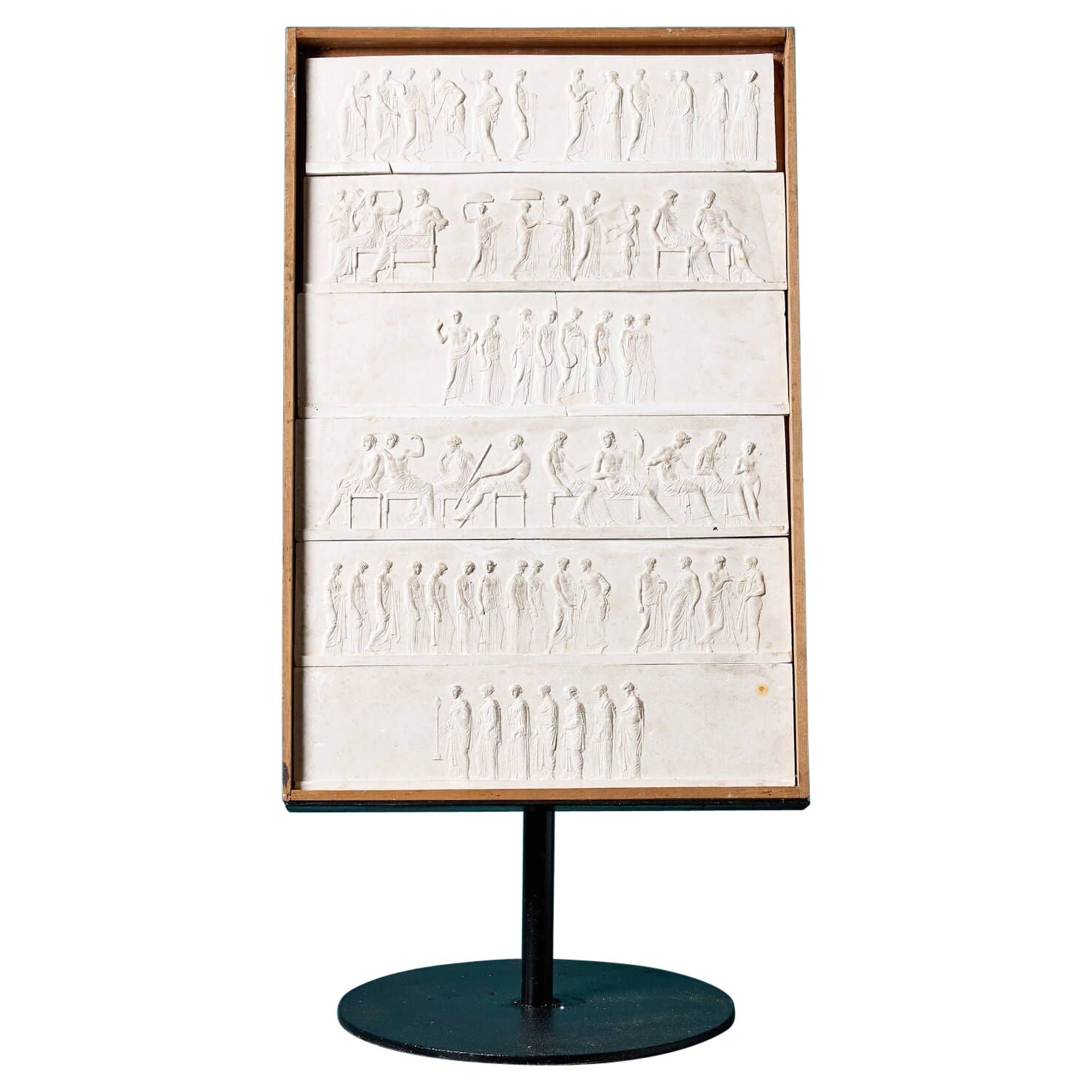

Collection of Antique Plaster Models After the Parthenon Frieze

Located in Wormelow, Herefordshire

A superb collection of 6 antique plaster models after the ancient 6th century BC Parthenon Frieze. Supplied loose, these mini friezes are presented in a wooden tray and mounted on a ...

Category

Antique Late 19th Century English Classical Greek Mounted Objects

Materials

Metal, Steel

Bronze Sculpture Of David By Michelangelo

Located in Madrid, ES

Bronze Sculpture Of David By Michelangelo

Large patinated bronze sculpture of David by Michelangelo. Excellent condition. 1950s. Dimensions: 84x2...

Category

Mid-20th Century Figurative Sculptures

Materials

Bronze

$1,222 Sale Price

20% Off

Turn of the Century Metal Sculpture after Michelangelo

Located in High Point, NC

This beautifully crafted bronze sculpture evokes the grandeur of Renaissance art. Made in France at the turn of the century, the piece is modeled after Michelangelo’s famous marble s...

Category

Antique Early 1900s French Figurative Sculptures

Materials

Bronze

Rare and important painted bronze Crucifix after a model by Michelangelo

By Michelangelo Buonarroti

Located in Leesburg, VA

A rare and very fine bronze corpus of Christ after a model by Michelangelo, cast ca. 1597-1600 by Juan Bautista Franconio and painted in 1600 by Francisco Pacheco in Seville, Spain.

The present corpus reproduces a model attributed to Michelangelo. The best known example, lesser in quality, is one on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET).

The association of this corpus with Michelangelo was first brought to light by Manuel Gomez-Moreno (1930-33) who studied the wider circulated casts identified throughout Spain. The attribution to Michelangelo was subsequently followed by John Goldsmith-Phillips (1937) of the MET and again by Michelangelo expert, Charles de Tolnay (1960).

While Michelangelo is best known for his monumental works, there are four documented crucifixes he made. The best known example is the large-scale wooden crucifix for the Church of Santa Maria del Santo Spirito in Florence, made in 1492 as a gift for the Prior, Giovanni di Lap Bicchiellini, for allowing him to study the anatomy of corpses at the hospital there. In 1562, Michelangelo wrote two letters to his nephew, Lionardo, indicating his intention to carve a wooden crucifix for him. In 1563 a letter between Lionardo and the Italian sculptor Tiberio Calcagni, mentions this same crucifix (a sketch of a corpus on the verso of a sheet depicting Michelangelo’s designs for St. Peter’s Basillica [Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille] may reproduce this). That Michelangelo was working on small corpora in the last years of his life is further evidenced by the small (26.5 cm) unfinished wooden crucifix located at the Casa Buonarroti, considered his last known sculptural undertaking. Michelangelo’s contemporary biographer, Giorgio Vasari additionally cites that Michelangelo, in his later years, made a small crucifix for his friend, Menighella, as a gift.

Surviving sketches also indicate Michelangelo’s study of this subject throughout his career, most notably during the end of his life but also during the 1530s-40s as he deepened his spiritual roots. The occasional cameo of crucified Christ’s throughout his sketched oeuvre have made it challenging for scholars to link such sketches to any documented commissions of importance. All the while, in consideration that such objects were made as gifts, it is unlikely they should be linked with commissions.

Nonetheless, a number of theories concerning Michelangelo’s sketches of Christ crucified have been proposed and some may regard the origin of the present sculpture. It has been suggested that the corpus could have its impetus with Michelangelo’s work on the Medici Chapel, whose exclusive design was given to the master. It is sensible smaller details, like an altar cross, could have fallen under his responsibility (see for example British Museum, Inv. 1859,0625.552). Others have noted the possibility of an unrealized large marble Crucifixion group which never came to fruition but whose marble blocks had been measured according to a sheet at the Casa Buonarroti.

A unique suggestion is that Michelangelo could have made the crucifix for Vittoria Colonna, of whom he was exceedingly fond and with whom he exchanged gifts along with mutual spiritual proclivities. In particular, Vittoria had an interest in the life of St. Bridget, whose vision of Christ closely resembles our sculpture, most notably with Christ’s proper-left leg and foot crossed over his right, an iconography that is incredibly scarce for crucifixes. The suggestion could add sense to Benedetto Varchi’s comment that Michelangelo made a sculpted “nude Christ…he gave to the most divine Marchesa of Pescara (Vittoria Colonna).”

Of that same period, two sketches can be visually linked to our sculpture. Tolnay relates it to a sketch of a Crucified Christ at the Teylers Museum (Inv. A034) of which Paul Joannides comments on its quality as suggestive of preparations for a sculptural work. Joannides also calls attention to a related drawing attributed to Raffaello da Montelupo copying what is believed to be a lost sketch by Michelangelo. Its relationship with our sculpture is apparent. Montelupo, a pupil of Michelangelo’s, returned to Rome to serve him in 1541, assisting with the continued work on the tomb of Pope Julius II, suggesting again an origin for the corpus ca. 1540.

The earliest firm date that can be given to the present corpus is 1574 where it appears as a rather crudely conceived Crucifixion panel, flanked by two mourners in low-relief and integrally cast for use as the bronze tabernacle door to a ciborium now located at the Church of San Lorenzo in Padula. Etched in wax residue on the back of the door is the date, 27 January 1574, indicating the corpus would have at least been available as a model by late 1573.

The Padula tabernacle was completed by Michelangelo’s assistant, Jacopo del Duca and likely has its origins with Michelangelo’s uncompleted tabernacle for the Basilica of St. Mary of the Angels in Rome.

The impetus for the Padula tabernacle’s Crucifixion panel begins with a series of late Crucifixion sketches by Michelangelo, depicting a scene of Christ crucified and flanked by two mourners (see British Museum Inv. 1895.0915.510; Ashmolean Museum Inv. 1846.89, KP II 343 recto; Windsor Castle RCIN 912761 recto; and Louvre Inv. 700). A faintly traced block possibly intended for sculpting the sketch of the crucified Christ on its recto was discovered by Tolnay on a version of the composition at Windsor Castle. The Windsor sketch and those related to it appear to have served as preparatory designs for what was probably intended to become the Basilica of St. Mary’s tabernacle door. Vasari documents that the project was to be designed by Michelangelo and cast by his assistant, Jacopo del Duca. Michelangelo died before the commission was complete, though on 15 March 1565, Jacopo writes to Michelangelo’s nephew stating, “I have started making the bronze tabernacle, depending on the model of his that was in Rome, already almost half complete.” Various circumstances interrupted the completion of the tabernacle, though its concept is later revitalized by Jacopo during preparations to sell a tabernacle, after Michelangelo’s designs, to Spain for Madrid’s El Escorial almost a decade later. The El Escorial tabernacle likewise encountered problems and was aborted but Jacopo successfully sold it shortly thereafter to the Carthusians of Padula.

An etched date, 30 May 1572, along the base of the Padula tabernacle indicates its framework was already cast by then. A 1573 summary of the tabernacle also describes the original format for the door and relief panels, intended to be square in dimension. However, a last minute decision to heighten them was abruptly made during Jacopo’s negotiations to sell the tabernacle to King Phillip II of Spain. Shortly thereafter the commission was aborted. Philippe Malgouyres notes that the Padula tabernacle’s final state is a mixed product of the original design intended for Spain’s El Escorial, recycling various parts that had already been cast and adding new quickly finished elements for its sale to Padula, explaining its unusually discordant quality, particularly as concerns the crudeness of the door and relief panels which were clearly made later (by January 1574).

Apart from his own admission in letters to Spain, it is apparent, however, that Jacopo relied upon his deceased master’s designs while hastily realizing the Padula panels. If Michelangelo had already earlier conceived a crucifix model, and Jacopo had access to that model, its logical he could have hastily employed it for incorporation on the door panel to the tabernacle. It is worth noting some modifications he made to the model, extending Christ’s arms further up in order to fit them into the scale of the panel and further lowering his chin to his chest in order to instill physiognomic congruence. A crude panel of the Deposition also follows after Michelangelo’s late sketches and is likewise known by examples thought to be modifications by Jacopo based upon Michelangelo’s initial sculptural conception (see Malgouyres: La Deposition du Christ de Jacopo del Duca, chef-d’oeuvre posthume de Michel-Ange).

Jacopo’s appropriation of an original model by Michelangelo for more than one relief on the Padula tabernacle adds further indication that the crucifix was not an object unique to Jacopo’s hand, as few scholars have posited, but rather belongs to Michelangelo’s original...

Category

Antique 16th Century Renaissance Figurative Sculptures

Materials

Bronze

Large Plaster 2 Setters On The Hunt Sculpture, 1920

Located in Saint-Amans-des-Cots, FR

Large French Art Deco Sculpture, 1920s – "Allez Hop" (Let’s Go). A captivating French Art Deco polychrome plaster sculpture from the 1920s, titled "Allez Hop" (Let’s Go). This dynami...

Category

Vintage 1920s French Art Deco Animal Sculptures

Materials

Plaster