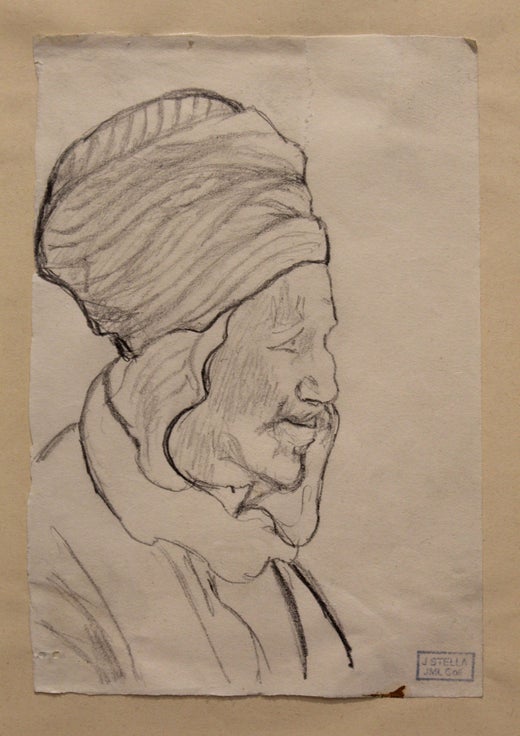

Joseph StellaLily and Birdc. 1919

c. 1919

About the Item

- Creator:Joseph Stella (1877-1946, American, Italian)

- Creation Year:c. 1919

- Dimensions:Height: 39 in (99.06 cm)Width: 32.13 in (81.62 cm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:New York, NY

- Reference Number:

Joseph Stella

Joseph Stella was a visionary artist who painted what he saw, an idiosyncratic and individual experience of his time and place. Stella arrived in New York in 1896, part of a wave of Italian immigrants from poverty-stricken Southern Italy. But Stella was not a child of poverty. His father was a notary and respected citizen in Muro Lucano, a small town in the southern Apennines. The five Stella brothers were all properly educated in Naples. Stella’s older brother, Antonio, was the first of the family to come to America. Antonio Stella trained as a physician in Italy, and was a successful and respected doctor in the Italian community centered in Greenwich Village. He sponsored and supported his younger brother, Joseph, first sending him to medical school in New York, then to study pharmacology, and then sustaining him through the early days of his artistic career. Antonio Stella specialized in the treatment of tuberculosis and was active in social reform circles. His connections were instrumental in Joseph Stella’s early commissions for illustrations in reform journals.

Joseph Stella, from the beginning, was an outsider. He was of the Italian-American community, but did not share its overwhelming poverty and general lack of education. He went back to Italy on several occasions, but was no longer an Italian. His art incorporated many influences. At various times his work echoed the concerns and techniques of the so-called Ashcan School, of New York Dada, of Futurism and, of Cubism, among others. These are all legitimate influences, but Stella never totally committed himself to any group. He was a convivial, but ultimately solitary figure, with a lifelong mistrust of any authority external to his own personal mandate. He was in Europe during the time that Alfred Stieglitz established his 291 Gallery. When Stella returned he joined the international coterie of artists who gathered at the West Side apartment of the art patron Conrad Arensberg. It was here that Stella became close friends with Marcel Duchamp.

Stella was 19 when he arrived in America and studied in the early years of the century at the Art Students League, and with William Merritt Chase, under whose tutelage he received rigorous training as a draftsman. His love of line, and his mastery of its techniques, is apparent early in his career in the illustrations he made for various social reform journals. Stella, whose later work as a colorist is breathtakingly lush, never felt obliged to choose between line and color. He drew throughout his career, and unlike other modernists, whose work evolved inexorably to more and more abstract form, Stella freely reverted to earlier realist modes of representation whenever it suited him. This was because, in fact, his “realist” work was not “true to nature,” but true to Stella’s own unique interpretation. Stella began to draw flowers, vegetables, butterflies, and birds in 1919, after he had finished the Brooklyn Bridge series of paintings, which are probably his best-known works. These drawings of flora and fauna were initially coincidental with his fantastical, nostalgic and spiritual vision of his native Italy which he called Tree of My Life (Mr. and Mrs. Barney A. Ebsworth Foundation and Windsor, Inc., St. Louis, illus. in Barbara Haskell, Joseph Stella, exh. cat. [New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994], p. 111 no. 133).

(Biography provided by Hirschl & Adler)

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Ships From: New York, NY

- Return PolicyThis item cannot be returned.

- Two Wood Ducks on a Flowering BranchBy Joseph StellaLocated in New York, NYJoseph Stella was a visionary artist who painted what he saw, an idiosyncratic and individual experience of his time and place. Stella arrived in New York in 1896, part of a wave of Italian immigrants from poverty-stricken Southern Italy. But Stella was not a child of poverty. His father was a notary and respected citizen in Muro Locano, a small town in the southern Appenines. The five Stella brothers were all properly educated in Naples. Stella’s older brother, Antonio, was the first of the family to come to America. Antonio Stella trained as a physician in Italy, and was a successful and respected doctor in the Italian community centered in Greenwich Village. He sponsored and supported his younger brother, Joseph, first sending him to medical school in New York, then to study pharmacology, and then sustaining him through the early days of his artistic career. Antonio Stella specialized in the treatment of tuberculosis and was active in social reform circles. His connections were instrumental in Joseph Stella’s early commissions for illustrations in reform journals. Joseph Stella, from the beginning, was an outsider. He was of the Italian-American community, but did not share its overwhelming poverty and general lack of education. He went back to Italy on several occasions, but was no longer an Italian. His art incorporated many influences. At various times his work echoed the concerns and techniques of the so-called Ashcan School, of New York Dada, of Futurism and, of Cubism, among others. These are all legitimate influences, but Stella never totally committed himself to any group. He was a convivial, but ultimately solitary figure, with a lifelong mistrust of any authority external to his own personal mandate. He was in Europe during the time that Alfred Stieglitz established his 291 Gallery. When Stella returned he joined the international coterie of artists who gathered at the West Side apartment of the art patron Conrad Arensberg. It was here that Stella became close friends with Marcel Duchamp. Stella was nineteen when he arrived in America and studied in the early years of the century at the Art Students League, and with William Merritt Chase, under whose tutelage he received rigorous training as a draftsman. His love of line, and his mastery of its techniques, is apparent early in his career in the illustrations he made for various social reform journals. Stella, whose later work as a colorist is breathtakingly lush, never felt obliged to choose between line and color. He drew throughout his career, and unlike other modernists, whose work evolved inexorably to more and more abstract form, Stella freely reverted to earlier realist modes of representation whenever it suited him. This was because, in fact, his “realist” work was not “true to nature,” but true to Stella’s own unique interpretation. Stella began to draw flowers, vegetables, butterflies, and birds in 1919, after he had finished the Brooklyn Bridge series of paintings, which are probably his best-known works. These drawings of flora and fauna were initially coincidental with his fantastical, nostalgic and spiritual vision of his native Italy which he called Tree of My Life (Mr. and Mrs. Barney A. Ebsworth Foundation and Windsor, Inc., St. Louis, illus. in Barbara Haskell, Joseph Stella, exh. cat. [New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994], p. 111 no. 133). Two Wood Ducks...Category

20th Century American Modern Still-life Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsColor Pencil

- UntitledBy Charles Houghton HowardLocated in New York, NYCharles Houghton Howard was born in Montclair, New Jersey, the third of five children in a cultured and educated family with roots going back to the Massachusetts Bay colony. His fat...Category

20th Century American Modern Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsPaper, Gouache, Graphite

- UntitledBy Charles Houghton HowardLocated in New York, NYCharles Houghton Howard was born in Montclair, New Jersey, the third of five children in a cultured and educated family with roots going back to the Massachusetts Bay colony. His fat...Category

20th Century American Modern Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsPaper, Watercolor, Gouache, Graphite

- Euclid Avenue, ClevelandBy Lawrence Edwin BlazeyLocated in New York, NYCleveland-born painter, advertising artist, and industrial designer Lawrence Blazey received his professional training at the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute). I...Category

Mid-20th Century American Modern Drawings and Watercolor Paintings

MaterialsPaper, Ink, Pencil

- UntitledBy Louisa ChaseLocated in New York, NYSigned (at lower right): Louisa Chase 1989Category

Late 20th Century American Modern Abstract Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsCharcoal, Ink, Watercolor, Pencil

- Profile of a WomanBy Elie NadelmanLocated in New York, NYPencil on paperCategory

Early 20th Century American Modern Drawings and Watercolor Paintings

MaterialsPencil

- SaltyBy Joseph BroghammerLocated in Kansas City, MODue to the current situation related to the Novel Coronavirus pandemic, our gallery will donate 10% of our commission from this sale to the Kansas City Artists Coalition, which has been supporting local Kansas City Artists for the past 40 years. The Kansas City Artists Coalition (KCAC), is a non-profit, artist-centered, artist-run alternative space, supporting artists at every level in their career through exhibitions, continuing education and artist studios. Artist: Joseph Broghammer Title: “Salty” Materials : Chalk pastel and pencil on Arches Paper Date : 2016 Dimensions : 20 ¼ x 24 in. Omaha based artist Joseph Broghammer is as much of a storyteller as he is an artist. His one-of-a-kind pastel drawings in “Animals” are chronicles of his life. The creatures Broghammer creates are vehicles to uncover the varying characteristics of the artist’s personal identity. Hence, Broghammer’s “Animals” translates as a flowing stream of consciousness. The different birds and livestock staring back at the viewer are ornamented with iconographic symbols – small surprises along the way. These trinkets are keys to understanding the stories Broghammer is sharing. Broghammer began mastering his “dry painting” technique during his B.F.A. in Visual Art at the University of South Dakota. He graduated in 1986 and a year later went on to study his M.F.A. at the University of Wisconsin. In 2009, he studied at Creative Capital in Omaha, Nebraska. As storytellers often do, Broghammer later went on to become an educator himself, teaching at WhyArts? and becoming an Artist Assistant at Vera Mercer...Category

2010s American Modern Paintings

MaterialsPastel, Color Pencil, Pencil, Archival Paper, Chalk

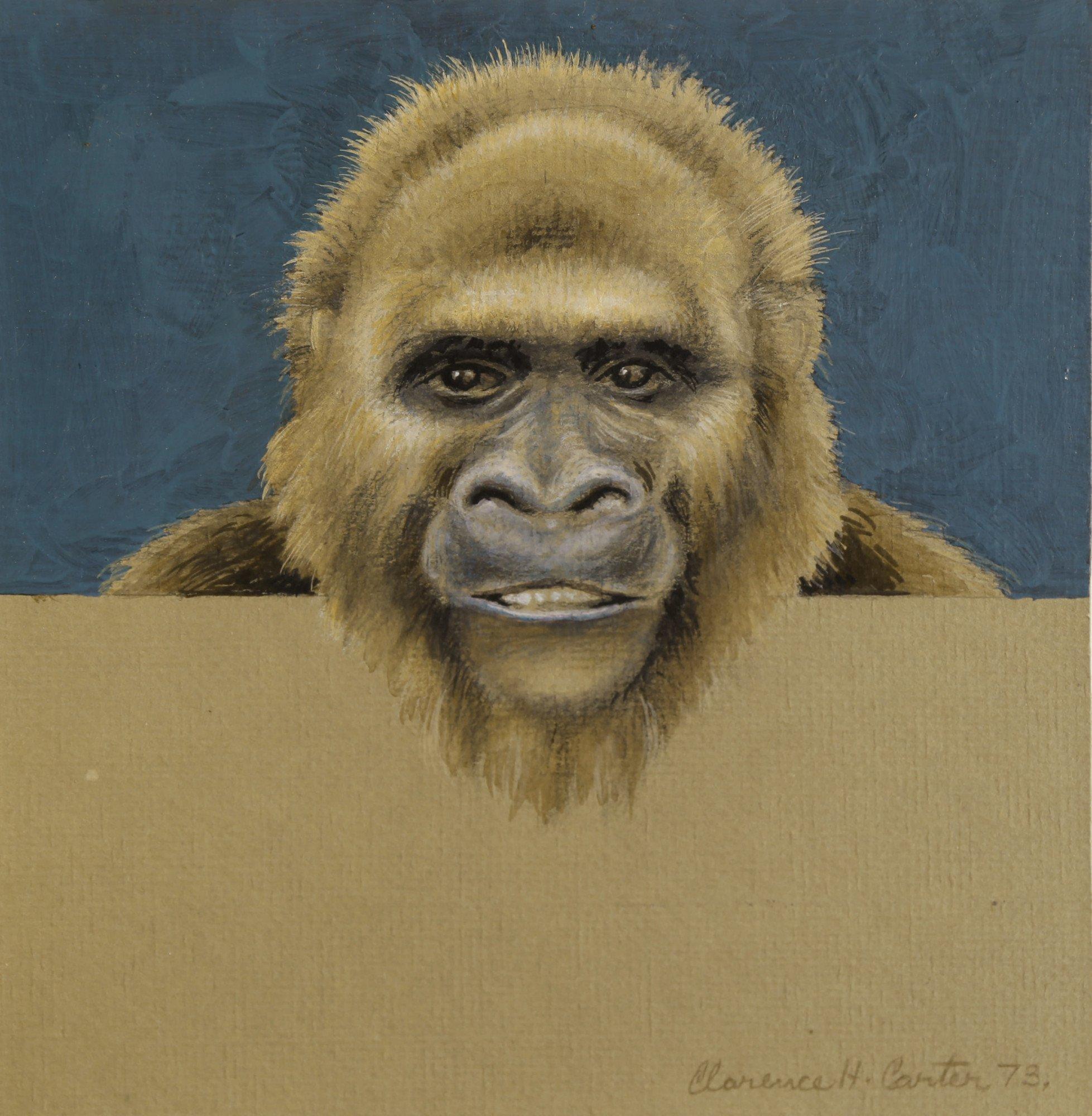

- Pappy (Study for Over and Above: Gorilla), Mid-Century Figurative DrawingBy Clarence Holbrook CarterLocated in Beachwood, OHClarence Holbrook Carter (American, 1904-2000) Pappy (Study for Over and Above: Gorilla), c. 1973 Colored pencil on paper Signed and dated lower left 7 x 7 inches 20.75 x 19 inches, framed Clarence Holbrook Carter achieved a level of national artistic success that was nearly unprecedented among Cleveland School artists of his day, with representation by major New York dealers...Category

1970s American Modern Animal Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsColor Pencil

- Blanche Grambs, (Young Bird with Ferns)Located in New York, NYBlanche Grambs, whose career started with the WPA, was an extremely skilled draftsperson. Her birds are masterful. This charming piece places the yooun...Category

1970s American Modern Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsPencil

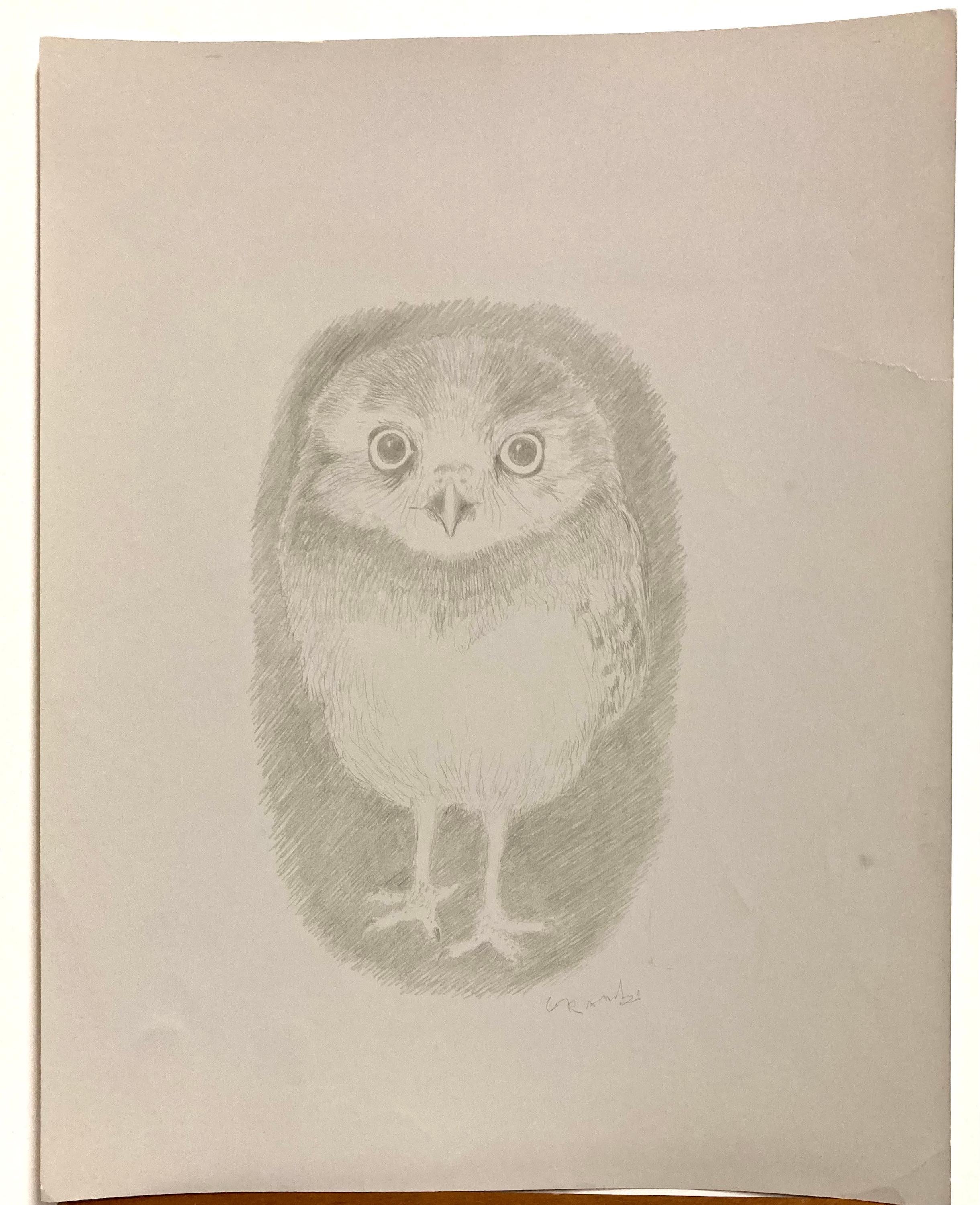

- Blanche Grambs, (Young Owl)Located in New York, NYBlanche Grambs, whose career started with the WPA, was an extremely skilled draftsperson. Her birds are masterful. Although we use the word 'pencil' fo...Category

1970s American Modern Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsPencil

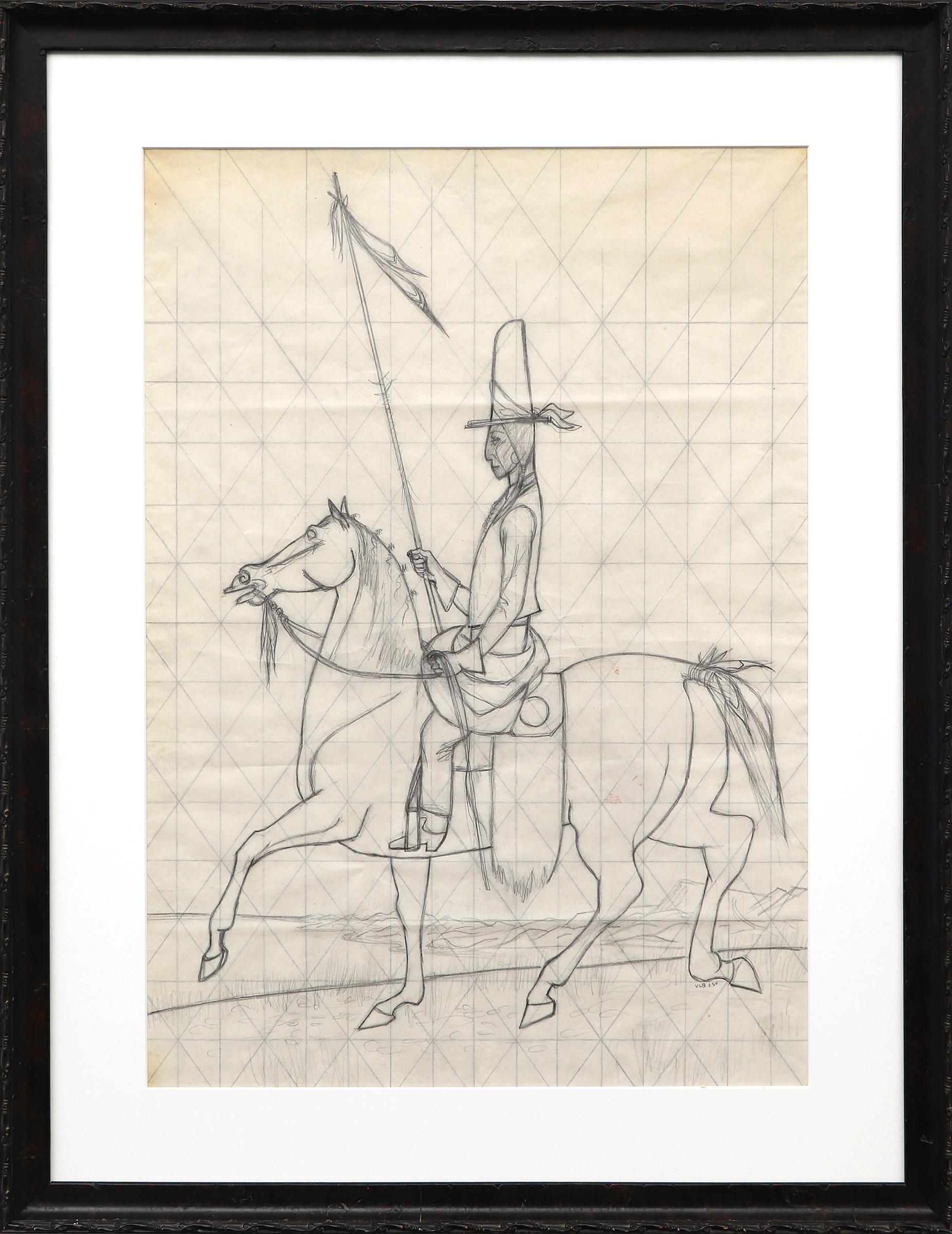

- Sketch for Mural, Figure on Horseback in Black and White Original DrawingLocated in Denver, COUntitled graphite on paper drawing by Verona Burkhard (1910-2004) of a figure on horseback. Preliminary sketch for a later completed mural. Presented in a custom frame with all archival materials, outer dimensions measure 29 ¾ x 22 ¾ inches. Image size is 23 ½ x 16 ¼ inches. Expedited and international shipping is available - please contact us for a quote. About the Artist: Verona Lorriane Burkhard was born on June 8, 1910 to of Henri and Verona P. (Turini) Burkhard, both of whom where artists. She was raised in New Jersey and New York where she studied at the Art Students League under Boardman Robinson and Columbia University under Frank Mechau...Category

20th Century American Modern Animal Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsGraphite

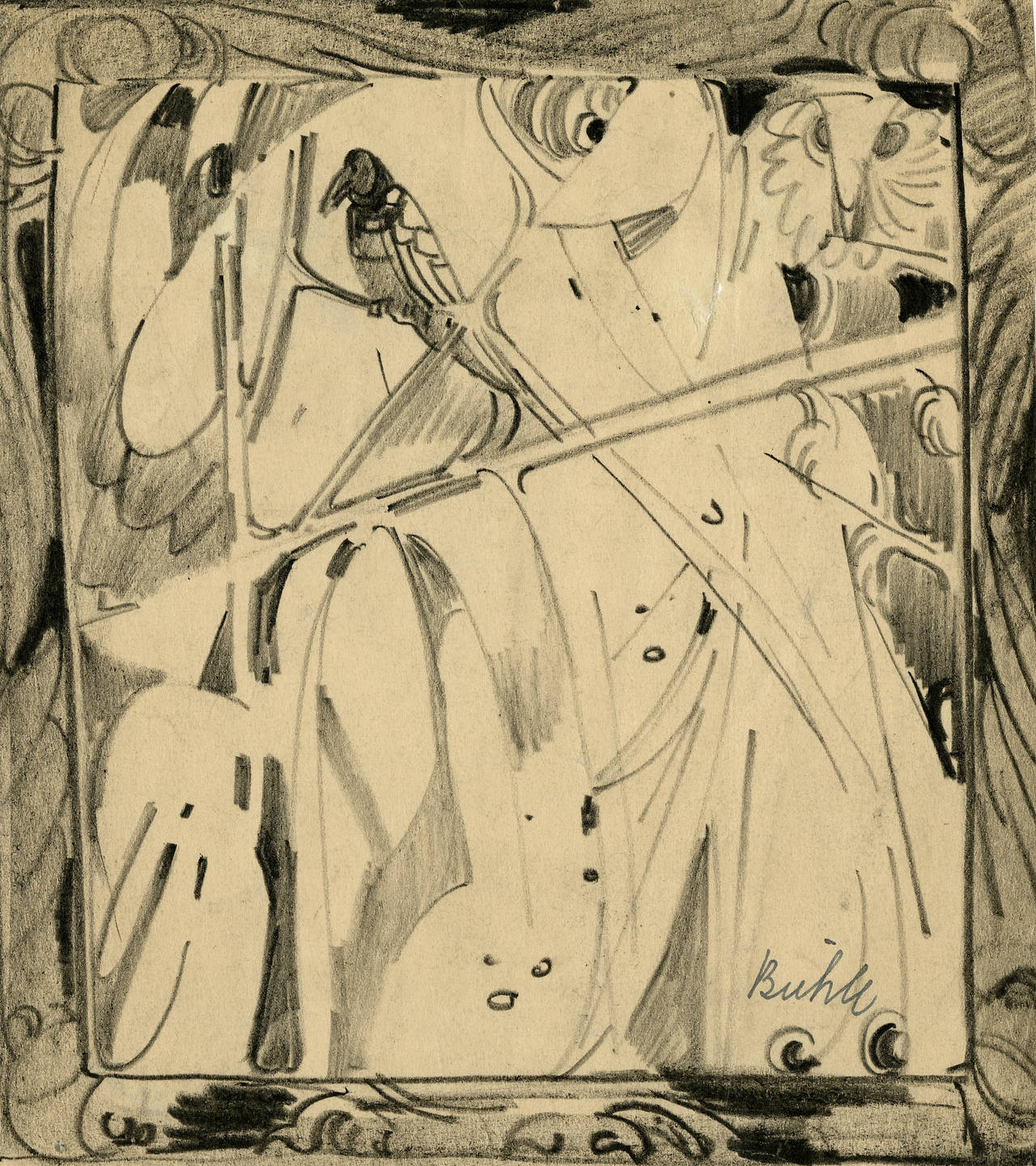

- untitled (Exotic Bird in Fantastic Landscape)By August F. BiehleLocated in Fairlawn, OHuntitled (Painting of Exotic Birds in Fantastic Landscape leaning against a wall)) Graphite on paper Signed by the artist in pencil lower right Pr...Category

1960s American Modern Animal Drawings and Watercolors

MaterialsGraphite

Recently Viewed

View AllRead More

With Works Like ‘Yours Truly,’ Arthur Dove Pioneered Abstract Art in America

New York gallery Hirschl & Adler is exhibiting the bold composition by Dove — who’s hailed as the first American abstract painter — at this year’s Winter Show.

Remarkably, Elizabeth Turk’s Sculptures Highlight the Lost Voices of Extinct Birds

In one of the first live and in-person exhibitions at a Manhattan gallery since last spring, the California-based sculptor gives the lost voices of endangered and extinct birds and animals a magnificent embodied form.