Items Similar to Life Magazine Art Deco Showgirls Cartoon

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 14

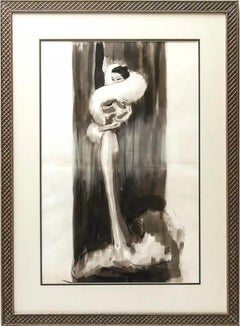

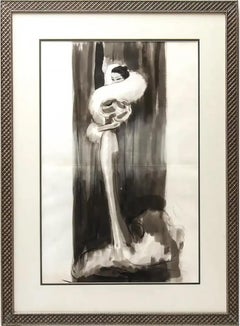

BARBARA SHERMUNDLife Magazine Art Deco Showgirls Cartoon1934

1934

$3,250

$5,00035% Off

£2,463.95

£3,790.6935% Off

€2,840.28

€4,369.6635% Off

CA$4,577.10

CA$7,041.7035% Off

A$5,075.67

A$7,808.7235% Off

CHF 2,666.89

CHF 4,102.9035% Off

MX$62,016.05

MX$95,409.3135% Off

NOK 33,366.40

NOK 51,332.9335% Off

SEK 31,320.07

SEK 48,184.7235% Off

DKK 21,203.24

DKK 32,620.3735% Off

About the Item

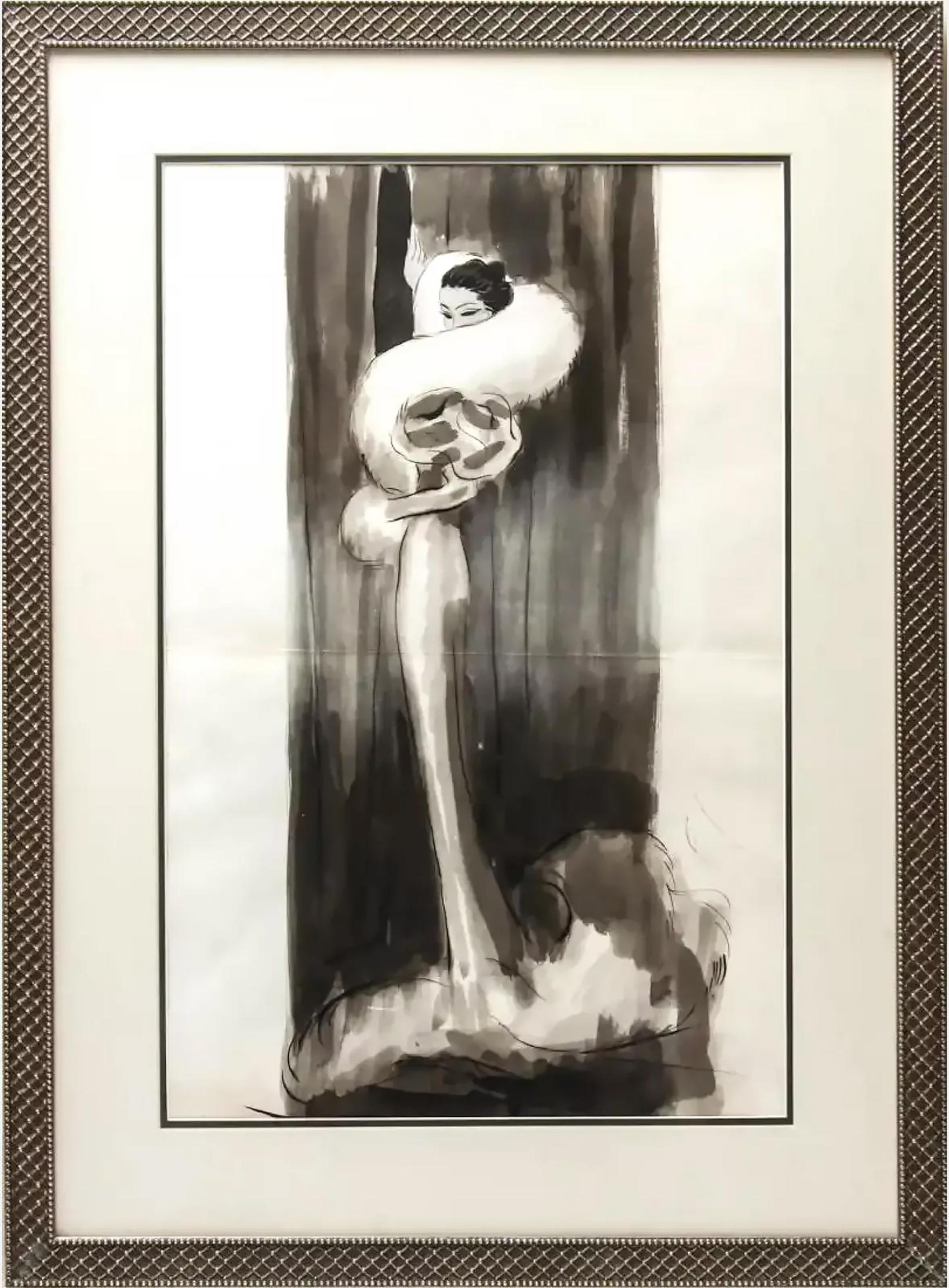

Barbara Shermund (1899-1978). Showgirls Cartoon for Life Magazine, 1934. Ink, watercolor and gouache on heavy illustration paper, matting window measures 16.5 x 13 inches; sheet measures 19 x 15 inches; Matting panel measures 20 x 23 inches. Signed lower right. Very good condition with discoloration and toning in margins. Unframed.

Provenance: Ethel Maud Mott Herman, artist (1883-1984), West Orange NJ.

For two decades, she drew almost 600 cartoons for The New Yorker with female characters that commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony.

In the mid-1920s, Harold Ross, the founder of a new magazine called The New Yorker, was looking for cartoonists who could create sardonic, highbrow illustrations accompanied by witty captions that would function as social critiques.

He found that talent in Barbara Shermund.

For about two decades, until the 1940s, Shermund helped Ross and his first art editor, Rea Irvin, realize their vision by contributing almost 600 cartoons and sassy captions with a fresh, feminist voice.

Her cartoons commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony, using female characters who critiqued the patriarchy and celebrated speakeasies, cafes, spunky women and leisure. They spoke directly to flapper women of the era who defied convention with a new sense of political, social and economic independence.

“Shermund’s women spoke their minds about sex, marriage and society; smoked cigarettes and drank; and poked fun at everything in an era when it was not common to see young women doing so,” Caitlin A. McGurk wrote in 2020 for the Art Students League.

In one Shermund cartoon, published in The New Yorker in 1928, two forlorn women sit and chat on couches. “Yeah,” one says, “I guess the best thing to do is to just get married and forget about love.”

“While for many, the idea of a New Yorker cartoon conjures a highbrow, dry non sequitur — often more alienating than familiar — Shermund’s cartoons are the antithesis,” wrote McGurk, who is an associate curator and assistant professor at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. “They are about human nature, relationships, youth and age.” (McGurk is writing a book about Shermund.

And yet by the 1940s and ’50s, as America’s postwar focus shifted to domestic life, Shermund’s feminist voice and cool critique of society fell out of vogue. Her last cartoon appeared in The New Yorker in 1944, and much of her life and career after that remains unclear. No major newspaper wrote about her death in 1978 — The New York Times was on strike then, along with The Daily News and The New York Post — and her ashes sat in a New Jersey funeral home for nearly 35 years until they were claimed by a descendant in search of information about her.

Barbara Shermund was born on June 26, 1899, in San Francisco. Her father, Henry Shermund, was an architect; her mother, Fredda Cool, a sculptor. Barbara displayed a knack for illustrating at a young age, and her parents encouraged her to explore her passion. She published her first cartoon when she was 8, in the children’s section of The San Francisco Chronicle.

Shermund’s mother died in 1918 in the Spanish flu pandemic. Some years later, her father married a woman 31 years his junior and eight years younger than Barbara. As her father and his new wife went on to build their own family, Barbara became estranged from them.

She attended the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) to study printmaking and painting and regularly won awards.

She moved to New York City in her mid-20s to seek an independent life while pursuing her artistic ambitions, finding work creating cover art, cartoons and illustrations for magazines like Esquire, Life and Collier’s.

She is believed to have met Harold Ross and Rea Irvin through mutual connections from her studies and in the magazine industry. Her contributions to The New Yorker included about nine cover illustrations as well as spot illustrations and section mastheads that helped set the magazine’s visual tone.

Her perspective was influenced by her intersection with profound historical moments: In addition to surviving the Spanish flu pandemic, Shermund lived through World War I and the suffrage movement.

One of her cartoons from the 1920s, after women won the right to vote, depicted two men in tuxedos smoking by a grand fireplace, with one saying in the caption, “Well, I guess women are just human beings, after all.”

In 1943, Esquire magazine sent Shermund to the Hollywood set of the musical comedy “Du Barry Was a Lady” to sketch actresses performing in an I Love an Esquire Girl sequence. She created as well a promotional poster for the film, starring Red Skelton and Lucille Ball.

She also took on advertising commissions at a time when women were rare in that industry, illustrating ads for companies like Pepsi-Cola, Ponds, Philips 66 and Frigidaire.

From 1944 until about 1957, she produced Shermund’s Sallies, a syndicated cartoon panel for Pictorial Review, the arts and entertainment section of Hearst’s many Sunday newspaper.

Shermund lived out her last years drawing at her home in Sea Bright, N.J., and swimming at a beach nearby. She died on Sept. 9, 1978, at a nursing home in Middletown, N.J.

“The women she drew and the captions she wrote showed us women who were not afraid of making fun of men, and showed us what it was really like to be a woman,” Liza Donnelly, a cartoonist and writer at The New Yorker, said in an interview. “Shermund’s women had humor and guts, just like what I imagine the artist had herself.”

Perhaps one of Shermund’s most striking pieces is indicative of her irreverent and fearless spirit in life: A young girl sits on the lap of a paternal figure and says, “Please, tell me a story where the bad girl wins!”

About the Seller

4.9

Platinum Seller

Premium sellers with a 4.7+ rating and 24-hour response times

Established in 2007

1stDibs seller since 2015

417 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 2 hours

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: Wilton Manors, FL

- Return Policy

Authenticity Guarantee

In the unlikely event there’s an issue with an item’s authenticity, contact us within 1 year for a full refund. DetailsMoney-Back Guarantee

If your item is not as described, is damaged in transit, or does not arrive, contact us within 7 days for a full refund. Details24-Hour Cancellation

You have a 24-hour grace period in which to reconsider your purchase, with no questions asked.Vetted Professional Sellers

Our world-class sellers must adhere to strict standards for service and quality, maintaining the integrity of our listings.Price-Match Guarantee

If you find that a seller listed the same item for a lower price elsewhere, we’ll match it.Trusted Global Delivery

Our best-in-class carrier network provides specialized shipping options worldwide, including custom delivery.More From This Seller

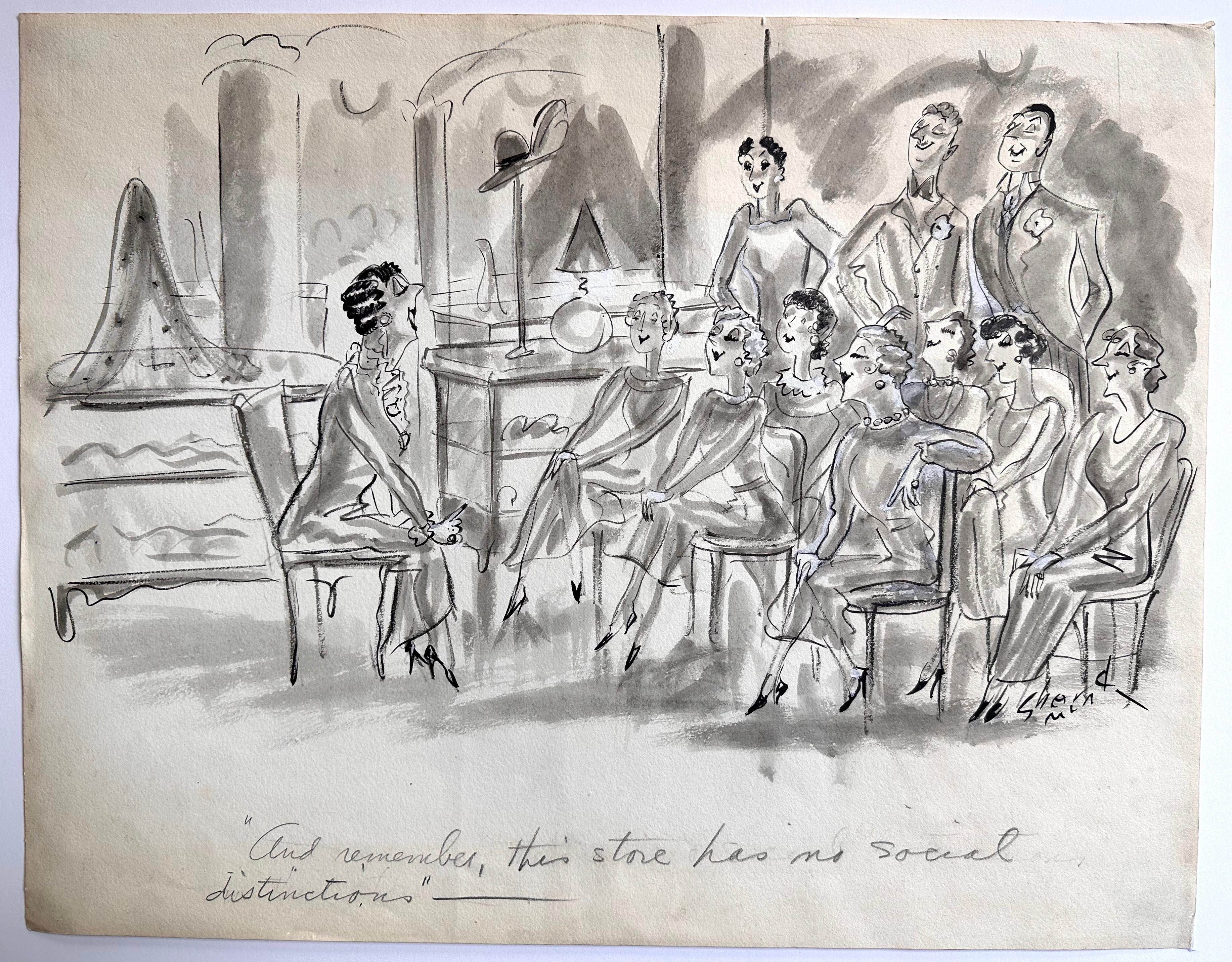

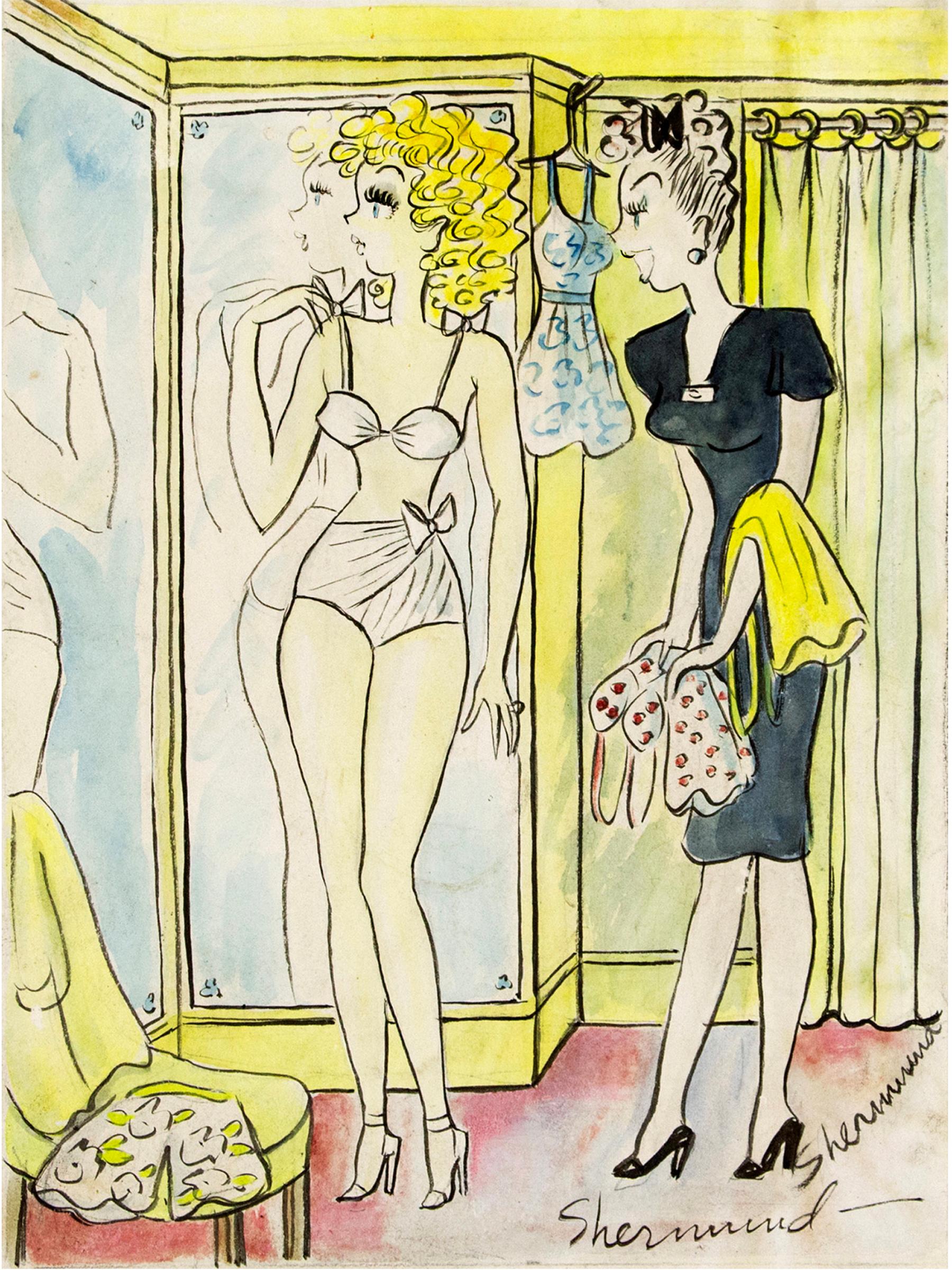

View AllFancy Department Store Satirical Cartoon

Located in Wilton Manors, FL

Barbara Shermund (1899-1978). Fancy Department Store Satirical Cartoon, ca. 1930's. Ink, watercolor and gouache on heavy illustration paper, panel measures 19 x 15 inches. Signed lower right. Very good condition. Unframed.

Provenance: Ethel Maud Mott Herman, artist (1883-1984), West Orange NJ.

For two decades, she drew almost 600 cartoons for The New Yorker with female characters that commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony.

In the mid-1920s, Harold Ross, the founder of a new magazine called The New Yorker, was looking for cartoonists who could create sardonic, highbrow illustrations accompanied by witty captions that would function as social critiques.

He found that talent in Barbara Shermund.

For about two decades, until the 1940s, Shermund helped Ross and his first art editor, Rea Irvin, realize their vision by contributing almost 600 cartoons and sassy captions with a fresh, feminist voice.

Her cartoons commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony, using female characters who critiqued the patriarchy and celebrated speakeasies, cafes, spunky women and leisure. They spoke directly to flapper women of the era who defied convention with a new sense of political, social and economic independence.

“Shermund’s women spoke their minds about sex, marriage and society; smoked cigarettes and drank; and poked fun at everything in an era when it was not common to see young women doing so,” Caitlin A. McGurk wrote in 2020 for the Art Students League.

In one Shermund cartoon, published in The New Yorker in 1928, two forlorn women sit and chat on couches. “Yeah,” one says, “I guess the best thing to do is to just get married and forget about love.”

“While for many, the idea of a New Yorker cartoon conjures a highbrow, dry non sequitur — often more alienating than familiar — Shermund’s cartoons are the antithesis,” wrote McGurk, who is an associate curator and assistant professor at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. “They are about human nature, relationships, youth and age.” (McGurk is writing a book about Shermund.

And yet by the 1940s and ’50s, as America’s postwar focus shifted to domestic life, Shermund’s feminist voice and cool critique of society fell out of vogue. Her last cartoon appeared in The New Yorker in 1944, and much of her life and career after that remains unclear. No major newspaper wrote about her death in 1978 — The New York Times was on strike then, along with The Daily News and The New York Post — and her ashes sat in a New Jersey funeral home...

Category

1930s Realist Figurative Paintings

Materials

Gouache, Ink

$1,875 Sale Price

25% Off

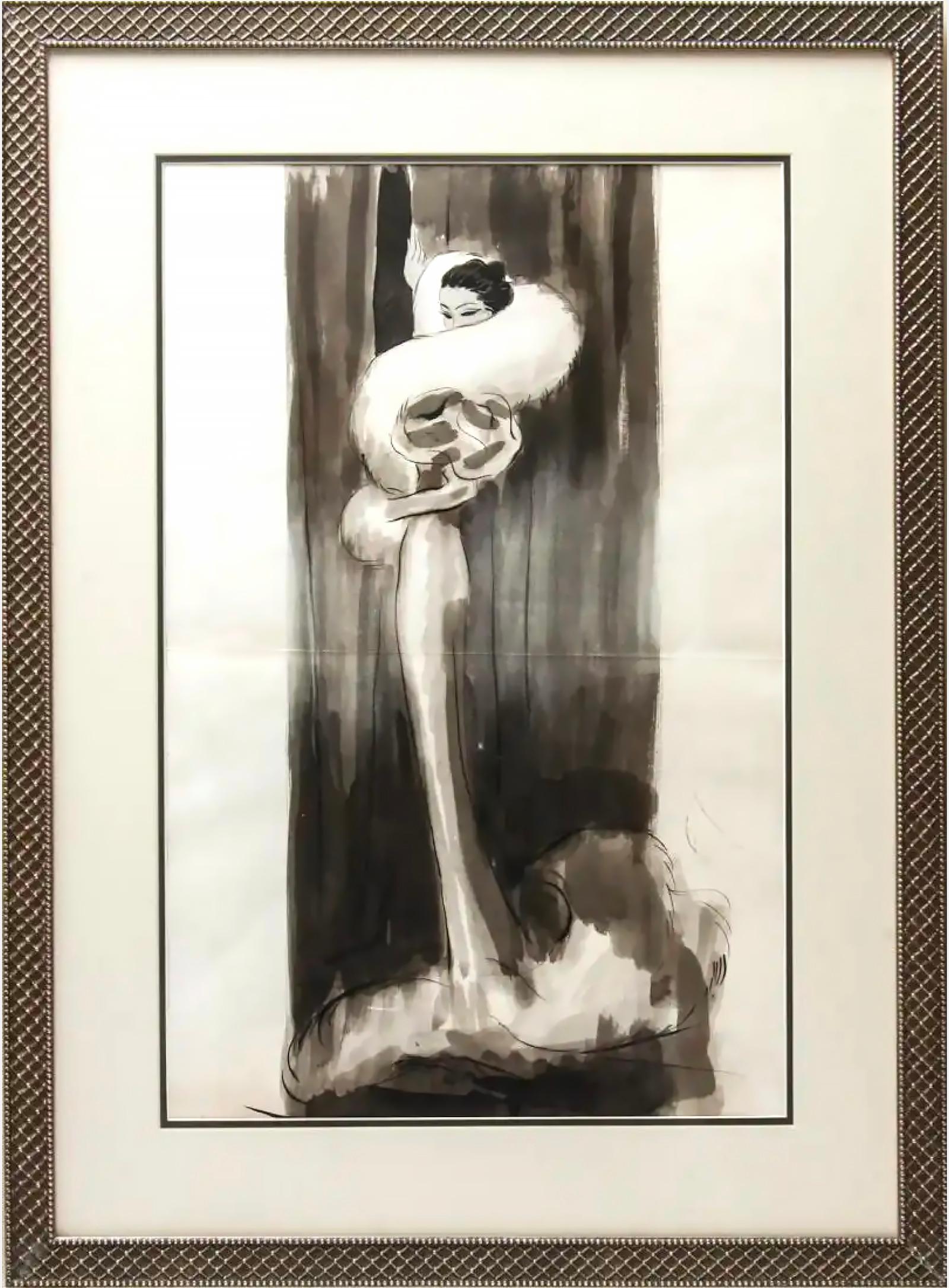

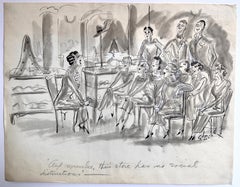

Life Magazine Satirical Society Cartoon Illustration

Located in Wilton Manors, FL

Barbara Shermund (1899-1978). Society Satirical Cartoon, ca. 1940s. Gouache on heavy illustration paper, image measures 17 x 14 inches; 23 x 20 inches in matting. Signed lower left. Very good condition but matting panel should be replaced. Unframed.

Provenance: Ethel Maud Mott Herman, artist (1883-1984), West Orange NJ.

For two decades, she drew almost 600 cartoons for The New Yorker with female characters that commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony.

In the mid-1920s, Harold Ross, the founder of a new magazine called The New Yorker, was looking for cartoonists who could create sardonic, highbrow illustrations accompanied by witty captions that would function as social critiques.

He found that talent in Barbara Shermund.

For about two decades, until the 1940s, Shermund helped Ross and his first art editor, Rea Irvin, realize their vision by contributing almost 600 cartoons and sassy captions with a fresh, feminist voice.

Her cartoons commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony, using female characters who critiqued the patriarchy and celebrated speakeasies, cafes, spunky women and leisure. They spoke directly to flapper women of the era who defied convention with a new sense of political, social and economic independence.

“Shermund’s women spoke their minds about sex, marriage and society; smoked cigarettes and drank; and poked fun at everything in an era when it was not common to see young women doing so,” Caitlin A. McGurk wrote in 2020 for the Art Students League.

In one Shermund cartoon, published in The New Yorker in 1928, two forlorn women sit and chat on couches. “Yeah,” one says, “I guess the best thing to do is to just get married and forget about love.”

“While for many, the idea of a New Yorker cartoon conjures a highbrow, dry non sequitur — often more alienating than familiar — Shermund’s cartoons are the antithesis,” wrote McGurk, who is an associate curator and assistant professor at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. “They are about human nature, relationships, youth and age.” (McGurk is writing a book about Shermund.

And yet by the 1940s and ’50s, as America’s postwar focus shifted to domestic life, Shermund’s feminist voice and cool critique of society fell out of vogue. Her last cartoon appeared in The New Yorker in 1944, and much of her life and career after that remains unclear. No major newspaper wrote about her death in 1978 — The New York Times was on strike then, along with The Daily News and The New York Post — and her ashes sat in a New Jersey funeral...

Category

1940s Realist Figurative Paintings

Materials

Gouache

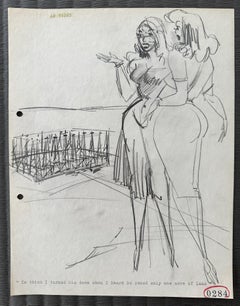

Humorous Gentleman's Magazine cartoon Oil Wells

Located in Wilton Manors, FL

Cartoon sketch, ca. 1955. Pencil on paper, sheet measures 8.5 x 11 inches. Unsigned with editor's notations.

From a group of sketches meant to be preliminary drafts for editor appro...

Category

Mid-20th Century Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Pencil

$125 Sale Price

50% Off

Showgirl (Chorus Girl drawing)

By Elmer Pirson

Located in Wilton Manors, FL

Elmer Pirson (1988-1935). Color pencil and paint on paper. Sheet measures 10.5 x 14 inches. Unframed and unmounted. Estate stamp on verso. Excellent condition.

An American Illustrator and painter, Elmer William Pirson was born in 1888 in New York.

Artistically, he is known to have studied under George Bridgman and James Earle Fraser...

Category

Early 20th Century Realist Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Color Pencil

Humorous Gentleman's Magazine cartoon

Located in Wilton Manors, FL

Cartoon sketch, ca. 1955. Pencil on paper, sheet measures 8.5 x 11 inches. Unsigned with editor's notations.

From a group of sketches meant to be preliminary drafts for editor appro...

Category

Mid-20th Century Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Pencil

$125 Sale Price

50% Off

Humorous Gentleman's Magazine cartoon

Located in Wilton Manors, FL

Cartoon sketch, ca. 1955. Pencil on paper, sheet measures 8.5 x 11 inches. Unsigned with editor's notations.

From a group of sketches meant to be preliminary drafts for editor appro...

Category

Mid-20th Century Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Pencil

$125 Sale Price

50% Off

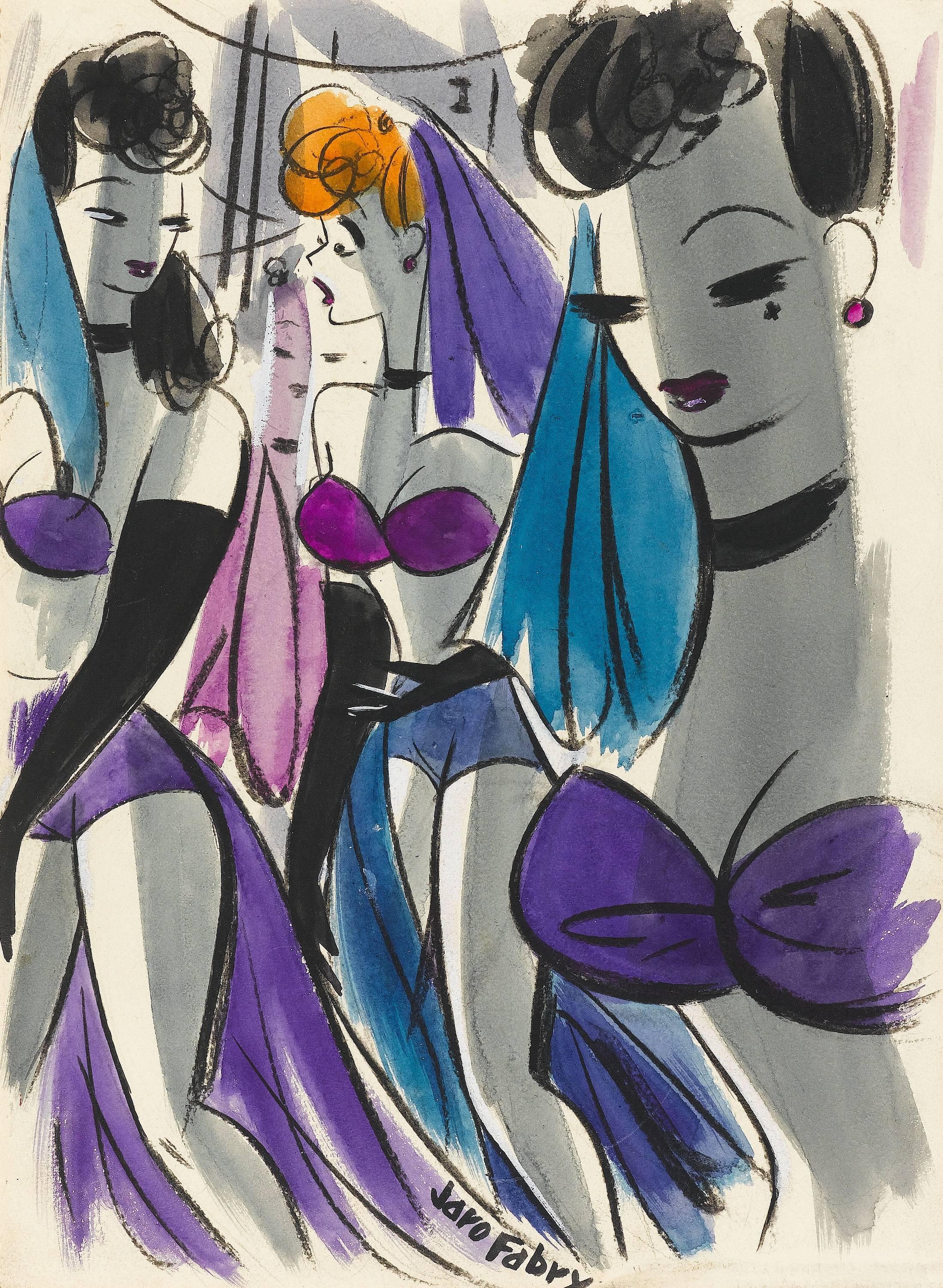

You May Also Like

Art Deco Glamour illustration, Golden Age of Hollywood

By Jaro Fabry

Located in Miami, FL

Caption: "He proposed this morning right

after the alarm clock went off."

From the Estate of Charles Martignette

Signed lower center

unframed

Category

1940s Art Deco Portrait Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Ink, Watercolor

Art Deco Vogue Magazine Illustration

By Edouard Garcia Benito

Located in Miami, FL

Art Deco "Mademoiselle X" story illustration

for Vogue February 1, 1934, watercolor and ink, reverse signed in pencil "Benito for Madame X," pencil inscription "Feb.1, 1934 / Page 51 / 316," accompanied by corresponding issue of Vogue magazine...

Category

1930s Art Deco Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Watercolor

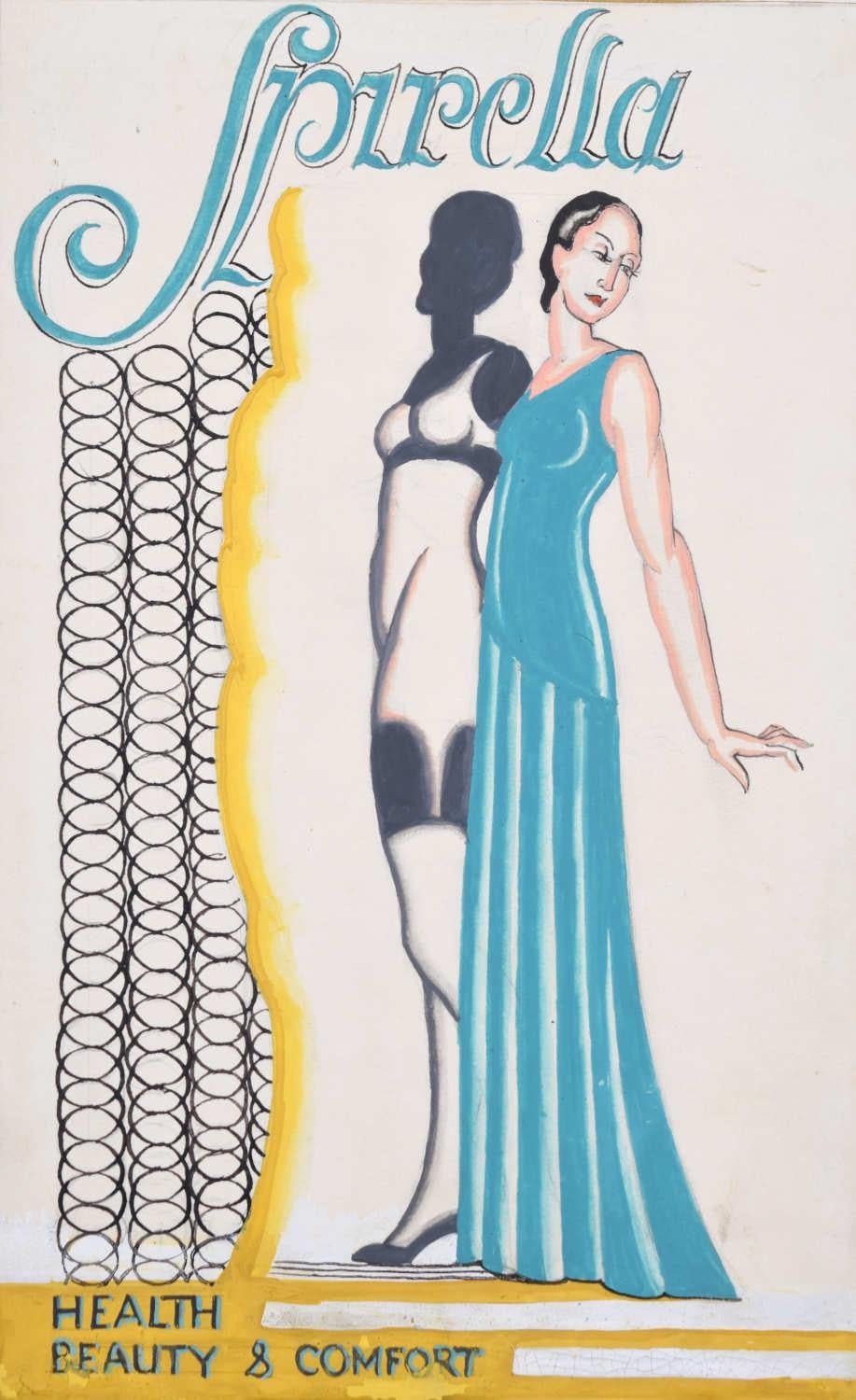

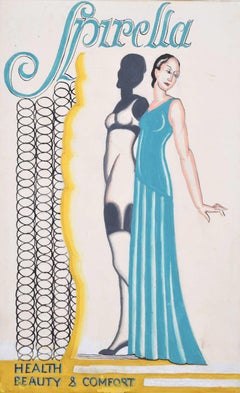

Spirella, Health, Beauty & Comfort, vintage illustration by A. E. Halliwell

Located in London, GB

A. E. Halliwell (1905-1987)

Spirella, Health, Beauty & Comfort

Gouache

26 x 15 cm

Provenance: Family of the artist

A.E. Halliwell (1905–1986) was a British artist, illustrator, a...

Category

1930s Art Deco Figurative Paintings

Materials

Ballpoint Pen

Vogue Magazine Illustration

Located in Miami, FL

"Mademoiselle X" story illustration

for Vogue February 1, 1934, watercolor and ink, reverse signed in pencil "Benito for Madame X," pencil inscription "Feb.1, 1934 / Page 51 / 316," ...

Category

1930s Art Deco Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Paper, Ink, Watercolor

Pondering being Naked - Sexy Girl taking off Bikini - Female Cartoonist

Located in Miami, FL

This work clearly has homosexual overtones which in the mid-'40s was as daring as showing nudity. I am not sure if this was the artist's intention but the salesgirl and the model look identical and she signs it twice Shermond. Added to this is a strobe light effect where the model's image is partly replicated giving the impression of 2 figures. She's lost in thought pondering the notion of removing the bows and seeing the consequences. Meanwhile, the sales girls ( perhaps her alta ego - perhaps an admirer ) eggs her on.

Caption: "You can always remove the bows if you think they're too fussy." Cover cartoon for unknown publication - Signed "Shermund" twice in the lower right image, dated on verso, and captioned in graphite in the lower margin. Original Matte and not framed - Barbara Shermund...

Category

1940s Feminist Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Ink, Watercolor, Graphite, Paper

Women - Drawing - Mid-20th Century

Located in Roma, IT

Women is a drawing realized in the Mid-20th Century.

Ink and watercolor on Paper.

Good conditions with slight foxing.

The artwork is realized through deft expressive strokes.

Category

Mid-20th Century Modern Figurative Drawings and Watercolors

Materials

Ink, Watercolor

More Ways To Browse

Art Deco Artists

Art Deco Red Art

Spanish Art Deco

Art Deco Panels

Magazine Covers Vogue

Art Deco Woman

Mens Magazine

Vintage Cartoons

1930 Art Deco Painting

Vintage Cartoon Art

Art Deco Vintage New York Poster

American Art Deco Painting

Esquire Magazine

Men Art Deco

Star Wars Vintage Art

Art Deco Painting 1920s

Vintage Art Deco Female

Art Deco Gouache