Light Art

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Pigment

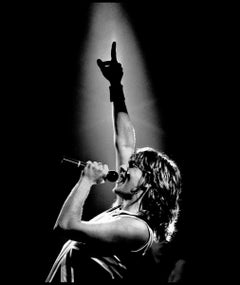

1980s Modern Portrait Photography

Black and White, Archival Pigment

2010s Contemporary Landscape Photography

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

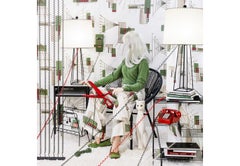

Early 2000s Contemporary Figurative Photography

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

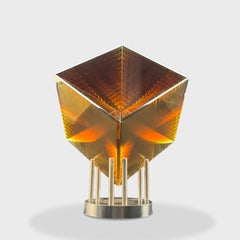

2010s Contemporary Figurative Sculptures

Glass

Early 2000s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Ink, Archival Paper, Color, Archival Pigment, Polaroid

1950s Modern Color Photography

Archival Pigment

1950s Modern Color Photography

Archival Pigment

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Pigment

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Ink, Archival Paper, Color, Archival Pigment, Polaroid

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Paper, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color

21st Century and Contemporary Realist Figurative Paintings

Wood, Oil

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Ink, Archival Paper, Color, Archival Pigment, Polaroid

2010s Contemporary Nude Photography

Photographic Film, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Pigment

2010s Pop Art Black and White Photography

Color, Archival Pigment

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Pigment, Encaustic, Wood Panel

1950s Modern Black and White Photography

Silver Gelatin, Black and White

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Color, Archival Pigment

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Color Photography

Photographic Paper, Archival Pigment

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Ink, Archival Paper, Color, Archival Pigment, Polaroid

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Ink, Archival Paper, Archival Pigment

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Pigment

21st Century and Contemporary Abstract Color Photography

Archival Pigment

1950s Interior Paintings

Gouache, Paper

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Pigment

2010s Modern Portrait Photography

Black and White, Archival Pigment

1970s Modern Portrait Photography

Archival Pigment

1950s Modern Color Photography

Archival Pigment

1960s Modern Black and White Photography

Black and White, Silver Gelatin

1980s Contemporary Color Photography

Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Silver Gelatin

21st Century and Contemporary American Realist Figurative Paintings

Oil

1960s Modern Landscape Paintings

Oil

2010s Contemporary Portrait Photography

Photographic Film, Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Polaroid

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Ink, Archival Paper, Archival Pigment

21st Century and Contemporary Pop Art Color Photography

Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Silver Gelatin

21st Century and Contemporary Street Art Prints and Multiples

Screen, Ink

2010s Modern Portrait Photography

Archival Pigment, Color

1960s Modern Landscape Photography

Color, Archival Pigment

2010s Landscape Photography

Photographic Paper

2010s Contemporary Landscape Photography

Archival Pigment

1990s Other Art Style Color Photography

Archival Pigment

2010s Contemporary Color Photography

Photographic Paper, C Print, Color, Silver Gelatin

21st Century and Contemporary Modern Black and White Photography

Silver Gelatin, Photographic Paper

2010s Contemporary Landscape Photography

Archival Ink, Archival Paper, Color, Archival Pigment

21st Century and Contemporary Figurative Paintings

Oil, Board

2010s Contemporary Black and White Photography

Silver Gelatin

Early 2000s Contemporary Prints and Multiples

Offset

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Figurative Paintings

Canvas, Oil

21st Century and Contemporary Other Art Style Color Photography

Photographic Paper, C Print

2010s Contemporary Figurative Paintings

Paint

2010s Contemporary Landscape Photography

Archival Pigment

1970s Pop Art Black and White Photography

Silver Gelatin

2010s Contemporary Landscape Photography

Archival Ink, Archival Paper, Color, Archival Pigment

2010s Contemporary Portrait Photography

Archival Ink, Archival Paper, Color, Archival Pigment

Early 20th Century Victorian Still-life Paintings

Watercolor

2010s Contemporary Photography

Photographic Paper, Archival Pigment

Early 2000s Contemporary Color Photography

Archival Pigment

1990s Modern Black and White Photography

Archival Pigment

2010s Contemporary Black and White Photography

Photographic Paper, Black and White, Archival Pigment

![carmen de vos The Enlightened Philosopher [From the series Famous in Flanders] - Polaroid](https://a.1stdibscdn.com/carmen-de-vos-photography-the-enlightened-philosopher-from-the-series-famous-in-flanders-polaroid-for-sale/a_6523/a_77383821616005515320/carmendevos_10_TheEnlightenedPhilosopher_master.jpg?width=240)