French modern art made a dramatic entrance into on America in 1913 at the famous Armory Show in New York City. In that same year, German twentieth-century art also arrived, with no fanfare, in the person of Winold Reiss, who disembarked from the S. S. Imperator on October 29, 1913, at Ellis Island in New York harbor. (The most accessible discussion of Reiss remains Jeffrey C. Stewart, To Color America: Portraits by Winold Reiss, exhib. cat. [Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 1989]. A very useful overview of Reiss’s career is contained in “Queen City Heritage: Cincinnati Union Terminal and the Artistry of Winold Reiss,” The Journal of the Cincinnati Historical Society 51 [Summer/Fall 1993]). Reiss was already twenty-seven years old when he came to America, thoroughly educated in a rigorous and inclusive heritage of German art that reflected decades of central European modernism.

Reiss’s father, Fritz Reiss (1857–1914), had trained as a landscape painter and portraitist at the renowned academy in Düsseldorf. Working as an illustrator, and proficient in watercolor as well as oil, Fritz Reiss moved his family, in the 1899, to Freiburg, a small village in southwest Germany near the Black Forest, so that he could paint honest portraits of local peasants. This choice reflected a prevailing spirit of romantic nationalism in the fine arts, architecture, and literature that was expressed in arts and crafts movements across Europe. Two of Fritz Reiss’s sons followed their father into art. Hans became a sculptor, immigrated to Sweden, and eventually joined his brother in America. Winold’s first art teacher was his father. In 1911, Reiss went to Munich where he studied with Franz von Stuck at the Academy of Fine Arts and with Julius Diez at the School of Applied Arts. Von Stuck was an influential art nouveau artist, designer, sculptor, and architect whose graphic style tended toward imaginative symbolism. Diez was master of mural painting who gained renown for his commercial poster designs executed in the Jugendstil manner. While Reiss absorbed stylistic influences from both of these men, perhaps the most lasting lesson was the freedom with which German fine artists crossed genres, working in the fine arts and the applied arts as circumstances warranted, without prejudice to their standing in either field. This permeable boundary, a characteristic of German arts and crafts practice, was also championed by John Ruskin and William Morris, in England. While his European versatility enabled Reiss to support his family in America, it ultimately hampered his full acceptance as a fine artist.

Reiss was proficient in graphics, fabric design, interior decoration, mural and poster art, as well as landscape and portrait painting. When he first arrived in America he established himself across a broad range of these interests, working in illustration, poster design, interior decoration, and as a teacher. His first major interior commission, the Busy Lady Bakery in New York City (Stewart, p. 30 illus.), strongly recalls the design work a decade earlier of Josef Hoffman in Vienna and Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow. While fellow German immigrants were among Reiss’s first commercial patrons, by 1915 he had been invited to lecture on the German poster at the Art Students League in New York. Anti-German feeling accompanying America’s entry into World War I derailed some of Reiss’s projects, but still, in 1914 and 1915, he designed covers for Scribner’s magazine.

None of this, however, was what had drawn Reiss to America. The story goes that he came to America to live out his childhood fantasies. Like many other German boys, Reiss had been captivated in his youth by tales of the American “wild west” widely circulated in the imaginative fiction of the German author Karl May. Reiss had also read, in translation, the works of James Fennimore Cooper. Numerous explanations can be put forth to explain Reiss’s emigration to America in 1913. The combined reasons must have been compelling enough to leave behind a pregnant wife (she and his son, Tjark, born in December 1913, joined him in America in 1914). These reasons included, no doubt, the war clouds over Europe, the increasing militarism of German society (Reiss’s brother Hans, was a pacifist) and the large number of artists already working in Germany. Still, for Reiss, America meant the Indian.

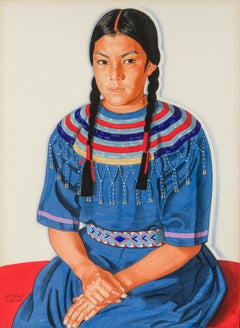

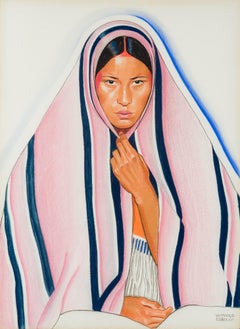

In January 1920, Reiss realized his dream of traveling west to Indian country. He went with a student to the Blackfoot Reservation in Browning, Montana. Thus began a relationship with Native Americans that lasted all of his life. Reiss produced thirty-six portraits of Blackfoot Indians in the winter of 1920. When he exhibited these in New York in 1920, at the E. F. Hanfstaengl Galleries, they were purchased as a group by Dr. Philip Cole, a native of Montana. In October 1920, Reiss made a sketching trip to Mexico, painting portraits and landscapes. As he traveled, Reiss’s style began to reflect the influence of the aesthetics, color palette, and patterns of indigenous American visual culture. He blended this into his now hyphenated German-American vocabulary, reaching for an artistic language expressed in the most universally accessible terms that would convey the respect he felt for all his subjects. The final major influence on Reiss’s style came in 1921, when, taking his eight-year-old son with him, he made his only return trip to Germany, where he visited his mother and sister. From September to the following May, Reiss traveled through Holland, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, and Czechoslovakia. In Oberammergau, he made nineteen portraits of actors in the passion plays. In Sweden, he sketched country people; and in Germany, returning to his paternal roots, he drew thirty-eight Black Forest residents. As importantly, he visited Munich and Berlin and saw the work of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) artists, whose fidelity to life as it is seen and to the social conditions of the people confirmed him in his own objectivity. Stewart (p. 44) suggests that Reiss was also influenced by seeing the work of Max Beckmann (he later had a 1924 Beckmann monograph in his personal library). When Reiss returned to America he produced a series of “imaginatives,”composite images of New York (and sometimes specifically Harlem) nightlife that recall Beckmann’s style. Reiss’s work, however, steered clear of the anger and direct political engagement of the German artists. He found positive energy in his city scenes and high spiritual values in his pre-industrial, pre-capitalist peasants.

One of the most notable aspects of Reiss’s modernism, and a point on which he emphatically parted ways from artists who prized unintelligibility as proof of aesthetic virtue, was that for Reiss his art could only be successful insofar as it found patrons to support it and a public to understand it. Reiss’s modern interiors were cheerful and welcoming; his portraits of marginalized populations—native Americans, Mexican peasants, and Negroes of the Harlem Renaissance as well as the offshore Georgia Sea Islands— invariably expressed the theme of a commonly shared human dignity.

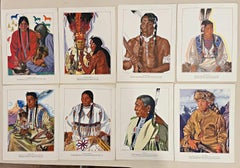

In New York, Reiss managed twin pursuits, becoming an influential teacher while maintaining a separate studio practice for his own work. He designed many well-known and well-loved commercial interiors, including, notably the chain of Longchamps restaurants in New York City and the splendid ballroom of the Hotel St. George in Brooklyn Heights. His Indian portrait work became part of the national visual culture when he acquired as a patron, Louis Hill, the owner of the Great Northern Railroad. In 1927, Hill purchased Reiss’s entire summer’s work, fifty-two portraits of American Indians. The relationship with the railroad proved long lasting and multi-faceted. The Great Northern used Reiss’s Indian portraits to illustrate months in its annual promotional calendars. Reiss’s designs also adorned the railroad’s menus, posters, and other promotional materials. Meanwhile he exhibited his work at the National Academy of Design, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Los Angeles Museum. In 1933, Reiss completed his designs for murals in the Cincinnati Union (Railroad) Terminal. These murals, threatened with destruction in 1972, were saved after a public hue and cry. Some remain in the former railroad station, now a cultural center, while others have been reinstalled at the Greater Cincinnati-Northern Kentucky International Airport, where they remain highly prized.

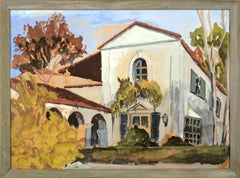

The present set of two oil paintings were part of a nine-part mural design commissioned by Henry Lustig for the interior of a Longchamps Restaurant that opened in 1936 at 1450 Broadway, in New York, one block south of Times Square. The back story of Longchamps colorful and fascinating. Henry Lustig had begun in business peddling fruit on New York’s Lower East Side. He advanced to the wholesale produce business and on the way married Edith Rothstein, sister of Arnold Rothstein. Rothstein, from a highly respected and well off family, was, from childhood, an inveterate gambler, a passion that led him to a career as the acknowledged head of a far flung network of illegal activities which he fashioned into an empire of organized crime as well as legitimate businesses. In 1919, Rothstein arranged for his brother-in-law, Lustig, to open the first Longchamps Restaurant on a property Rothstein owned at 78th Street and Madison Avenue. Lustig, also a gambler who owned racehorses, named his premises after the famous racecourse outside of Paris. Rothstein was murdered in 1926, though he and Lustig likely fell out before that. (Truth is hard to separate from myth in discussions of Rothstein. Called “the Brain,” he is widely understood to have been the model for Meyer Wolfsheim in The Great Gatsby, as well as the model for characters in The Godfather and HBO’s Boardwalk.)

With the end of Prohibition in December 1933, Lustig opened a series of Longchamps restaurants at high profile locations around Manhattan. The restaurants were intended to be elegant, serving sophisticated food and drink in glamourous surroundings to a reliable crowd of “regulars” who had money, but also accessible to middle class patrons looking for celebratory meals. Lustig hired top architects, Louis Alan Abramson and Ely Jacques Kahn. In fact, Kahn had designed 1450 Broadway, a 42-story office building called “The Continental” that opened in 1931 (and remains to this day). These were the years of the Great Depression and Lustig was commissioning interiors for patrons who wanted to wine and dine in settings worthy of a Busby Berkeley film.

For his interiors, Henry Lustig turned to Winold Reiss. Reiss already boasted a portfolio ready made for Lustig’s purposes. Through his shipmate friend of 1913, Alfons L. Baumgarten, Reiss had connected with Baumgarten’s brother Otto, already in New York and intent on going into the restaurant business. Baumgarten’s father owned a restaurant in Vienna and, in 1919, Reiss served as the designer for Baumgarten’s Restaurant Crillon. The commission attracted favorable notice and Reiss went on to design interiors and packaging for Baumgarten’s Café Viennois and for his candy business, Baumgarten Viennese Bonbonniѐre. In 1923, Reiss decorated rooms and hallways and designed interiors and murals for the restaurant and night club at the top of the Hotel Alamac, a new 19-story hotel at 71st Street and Broadway that advertised itself as “three minutes from Times Square,” a reference to its location one express

subway stop...