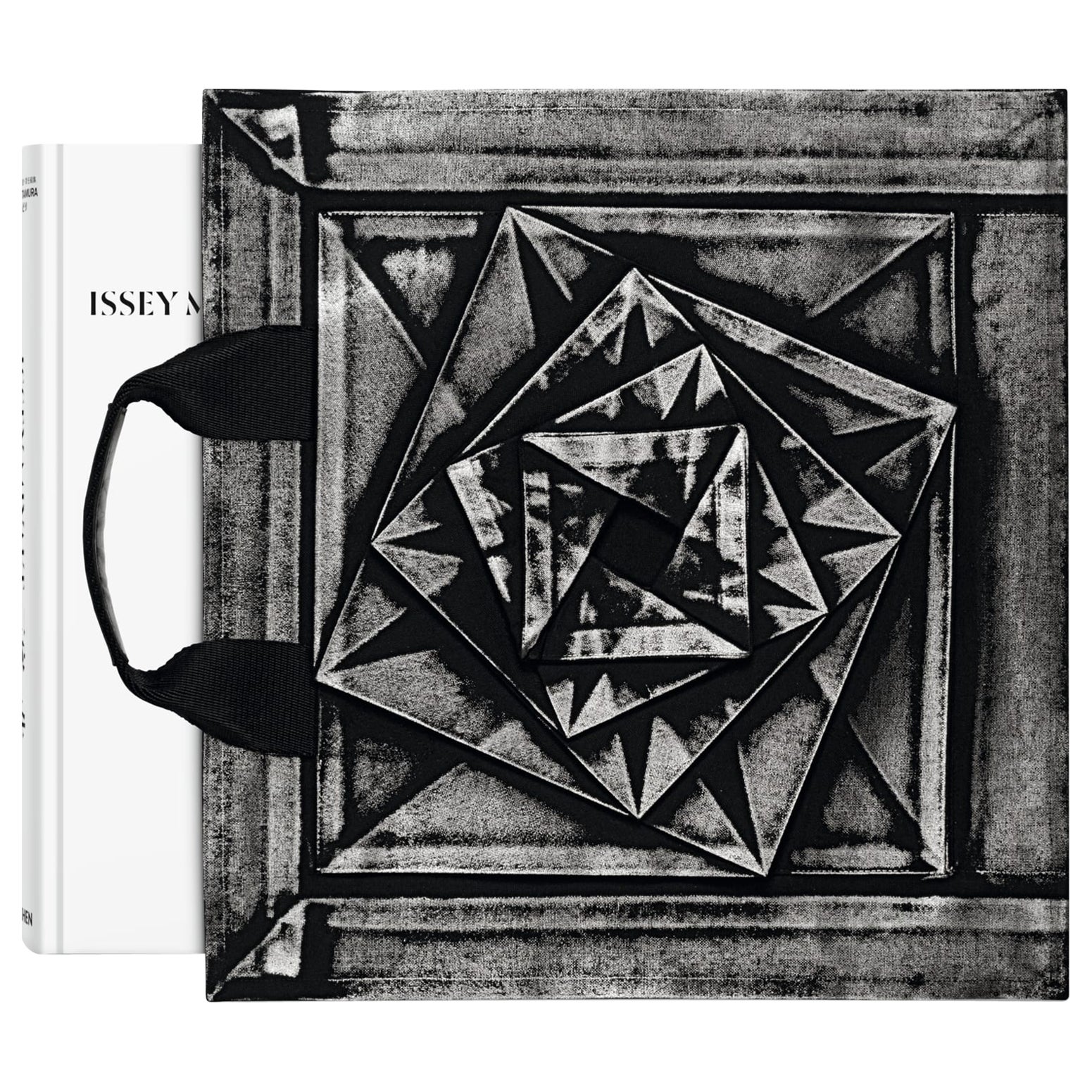

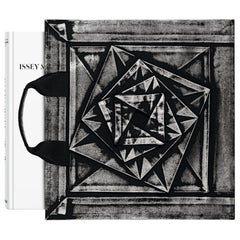

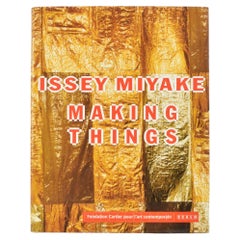

Issey Miyake, Photographs by Irving Penn, Little, Brown and Company, 1988

About the Item

- Creator:Irving Penn (Photographer),Issey Miyake (Author)

- Dimensions:Height: 1.03 in (2.6 cm)Width: 11.03 in (28 cm)Depth: 12.6 in (32 cm)

- Materials and Techniques:

- Place of Origin:

- Period:

- Date of Manufacture:1988

- Condition:Wear consistent with age and use. Near Fine.

- Seller Location:CA, CA

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU2102332395262

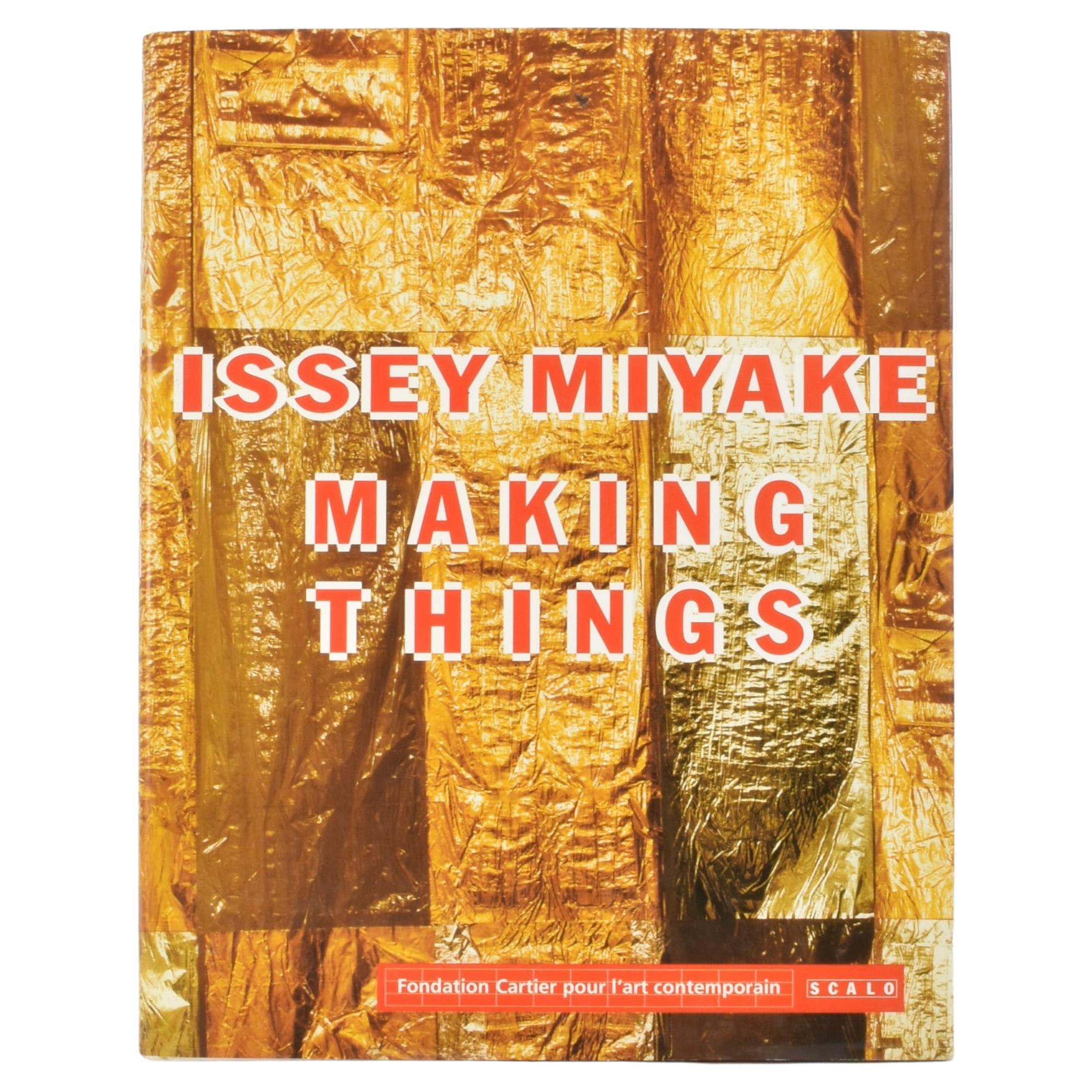

Issey Miyake

From the prismatic Pleats Please collection to the modular, three-dimensional garments crafted from recycled plastic bottles in his Reality Lab, the captivating fashions by Japanese designer Issey Miyake are all about movement.

Born in Hiroshima, Miyake studied graphic design at Tama Art University in Tokyo before relocating to Paris in 1965, where he studied couture and cut his teeth working for Guy Laroche and Hubert de Givenchy. In 1969, he moved to New York, where he worked for Geoffrey Beene. He returned to Tokyo in 1970 to found his first solo venture, the Miyake Design Studio. It wasn’t until the 1990s, though, that the designer had his breakthrough moment with experimentations in pleating. Some of his earliest explorations were for choreographer William Forsythe’s Frankfurt Ballet Company, with the 1991 performance of The Loss of Small Detail featuring costumes Miyake designed with pleats that complemented and transformed the movement of the dancers.

Though long a staple in couture — from delicate women’s skirts to men’s suit pants — pleats took on new life in Miyake’s hands. By using a heat press to cure his fabrics after his garments are stitched, Miyake was able to maintain the accordion structure of the pleat, turning a series of folds into sculptural, often futuristic forms unbound by the shape of the human body. In 1993, Miyake debuted “garment pleating” in his Pleats Please line, in which the clothes are constructed at a size that is larger than what is intended for the finished product. The pleats are then created — a process that involves folding and ironing and is separate from the joining of seams — and individual pieces are subsequently hand-fed into a heat press. The pleats are permanent and the garments can be worn and washed without losing their shape.

Miyake’s pleats run the gamut in scale, which enabled him to evoke dramatic, sharp silhouettes and flowy movements in equal measure. In essence, he created an entirely new material whose iterations are infinite — a feat of technology as much as fashion.

Other innovations include Miyake’s 1997 Just Before collection, which introduced a series of tube-knit dresses that could be cut as desired, reducing both work and resources. His Reality Lab now investigates new materials, such as a fully recycled polyester. Miyake’s prowess, in fact, captured another iconic figure in the tech world: Steve Jobs, for whom the designer made hundreds of identical black turtlenecks, the late Apple founder’s sartorial signature.

Find a collection of vintage Issey Miyake day dresses, jackets, shirts and other clothing on 1stDibs.

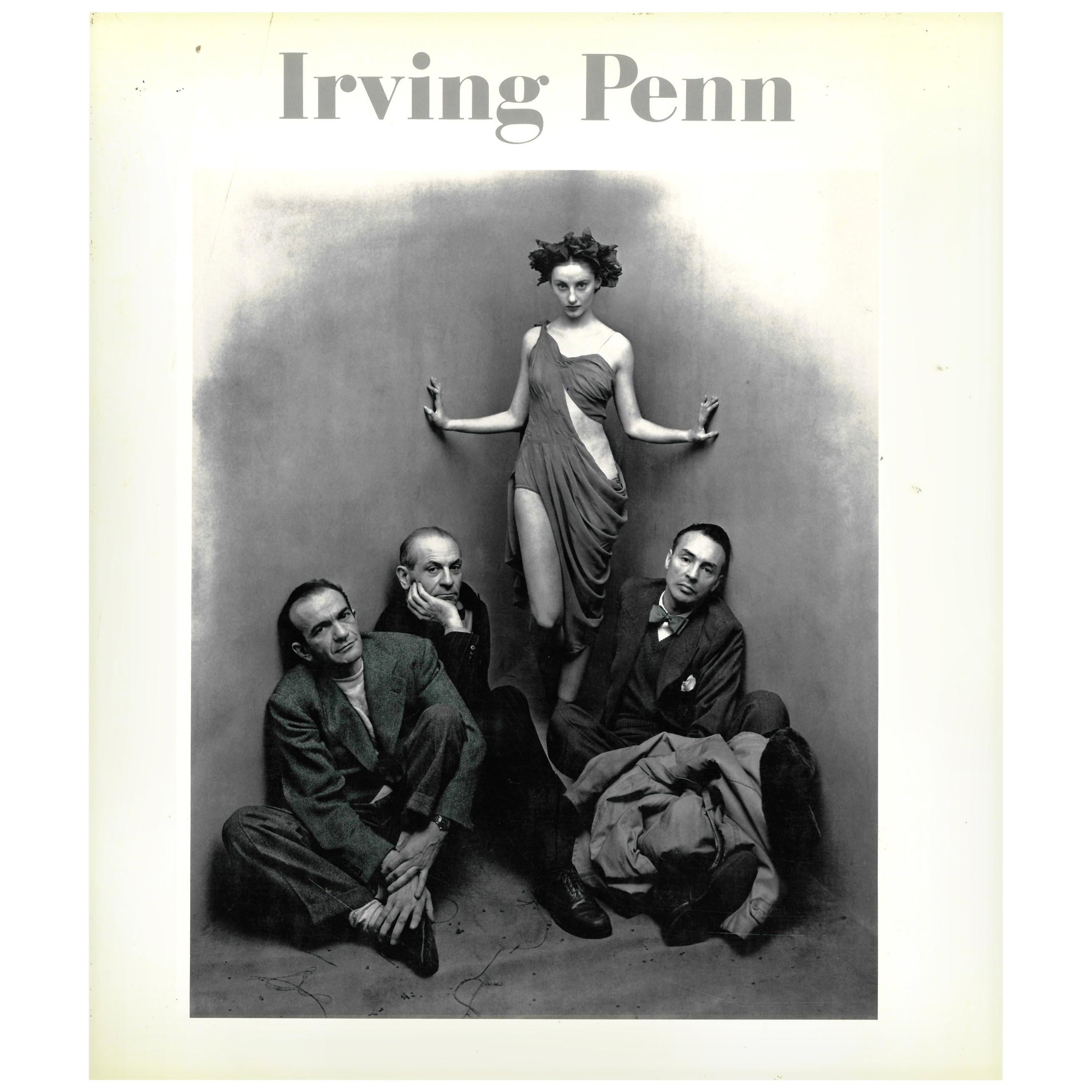

Irving Penn

With a career in magazines that spanned the mid-20th century heyday of print journalism and lasted through the first decade of the 21st, Irving Penn was the preeminent photographer for six decades at Vogue, where he worked right up until his death, in 2009, at age 92.

Penn’s refined and dynamic photography of models, celebrities and products like Clinique and Jell-O pudding, all shot in compositions of stunning equipoise in the cool remove of his minimal studio setups, were designed to stop traffic and cut through the clutter of magazine pages.

Penn flourished under the mentorship of two legendary art directors: Harper’s Bazaar‘s Alexey Brodovitch and Vogue‘s Alexander Liberman, both Russian émigrés like Penn’s father. Brodovitch introduced Penn to Surrealism and avant-garde photography as his teacher at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art and hired him as his assistant at Harper’s Bazaar during the summers of 1937 and ’38. Penn bought his first camera after graduating that year. He met Liberman in 1941, passing off to the recent New York transplant his freelance art director job at Saks Fifth Avenue. Liberman returned the favor by hiring Penn at Vogue in 1943 to sketch cover concepts, later encouraging him to shoot his unconventional juxtapositions of accessories and household items himself.

Assigned to photograph some portraits in the mid-1940s, Penn took a cue from the stage-set windows at Saks. He angled two studio flats in his studio and placed his subjects, including Truman Capote, Jerome Robbins and Salvador Dalí, in the resulting tight corner, literally and psychologically. Spencer Tracy leans jauntily against the walls in his portrait, while Georgia O'Keeffe simmers straight-armed in her confinement.

Penn didn’t work well with the distractions of the outside world. In 1950, when he was instructed by Liberman to buy an evening jacket and shoot the couture shows in Paris, he managed the assignment by having the dresses brought to him. He rented a top-floor studio with great light but no electricity and photographed models, including Lisa Fonssagrives (whom he married shortly after), against a mottled gray theater curtain that he continued to use for the rest of his career. Between deliveries from Dior and Balenciaga, he began his personal project “Small Trades,” in which he had local Parisians — a knife grinder, a mailman, a cucumber seller — pose for him with tools of their trade against the same backdrop. (He extended the series in London and New York.)

While Penn made bold, reductive still lifes for advertising campaigns throughout his career, in 1972 he applied his sculptural understanding of form to the unlikeliest of subjects: cigarette butts he gathered from the streets. The Museum of Modern Art showed Penn’s cigarette butts in 1975, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibited another series of material salvaged from the street in 1977. At this time, Penn also began revisiting his earlier photographs, reprinting them at larger scale and with the more painterly quality achieved with the platinum-palladium process. In his lush, oversized platinum-palladium prints, he elevates the lowly castoffs to heroic objects worthy of archaeological scrutiny.

Find vintage Irving Penn photography on 1stDibs.

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: CA, CA

- Return Policy

More From This Seller

View AllVintage 1980s Books

Paper

Mid-20th Century British Books

Vintage 1980s Books

Paper

Mid-20th Century British Mid-Century Modern Books

Paper

Vintage 1970s Books

Paper

Vintage 1940s Books

Paper

You May Also Like

21st Century and Contemporary Japanese Books

Foil

20th Century Books

Paper

20th Century Books

Paper

1990s Books

Paper

Antique Late 19th Century American Books

Leather

Antique 1870s American Scientific Instruments

Brass