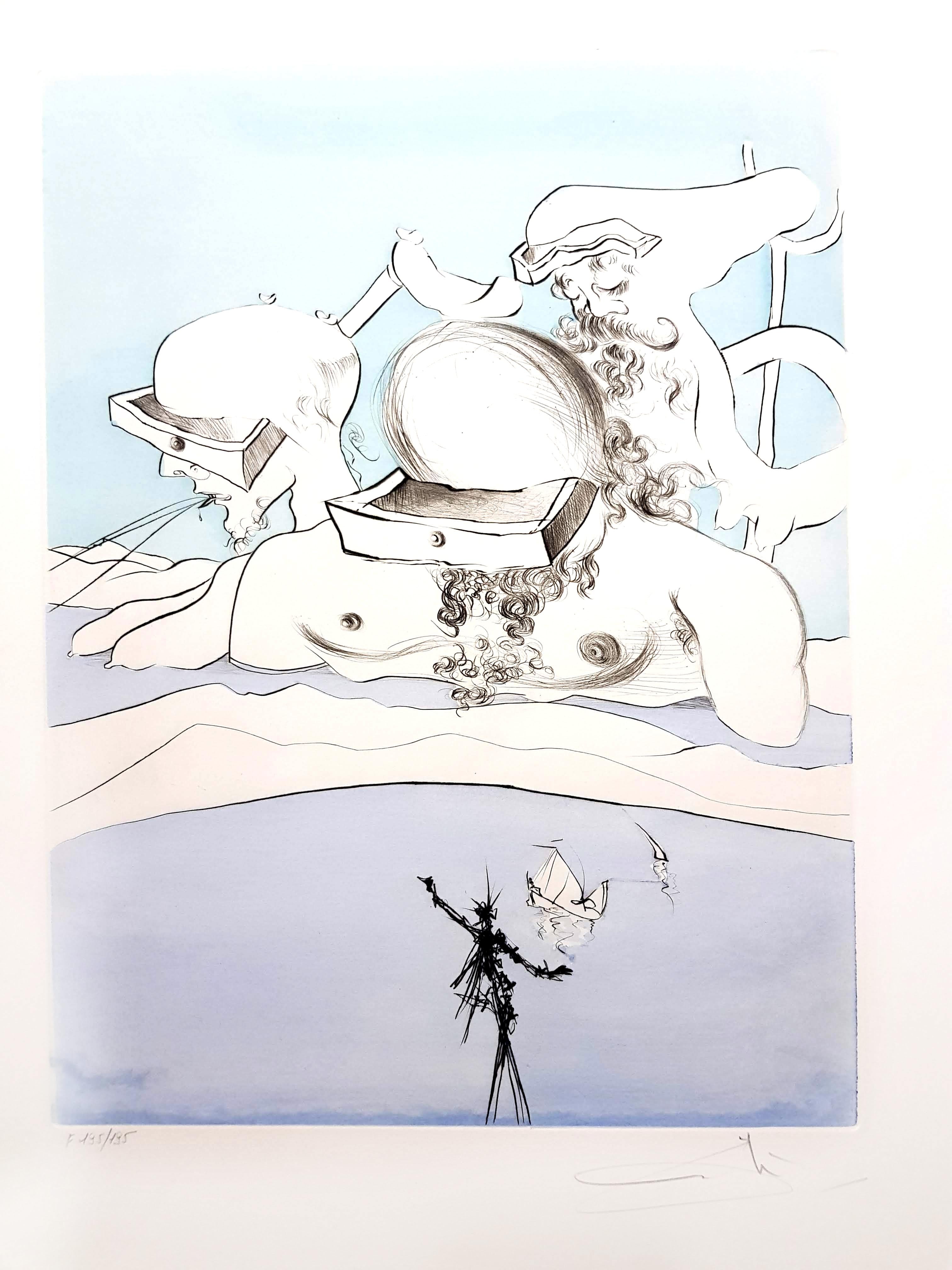

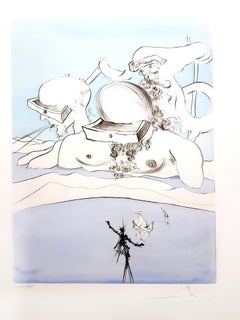

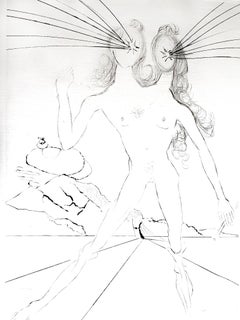

Hans Bellmer German (1902–1975)

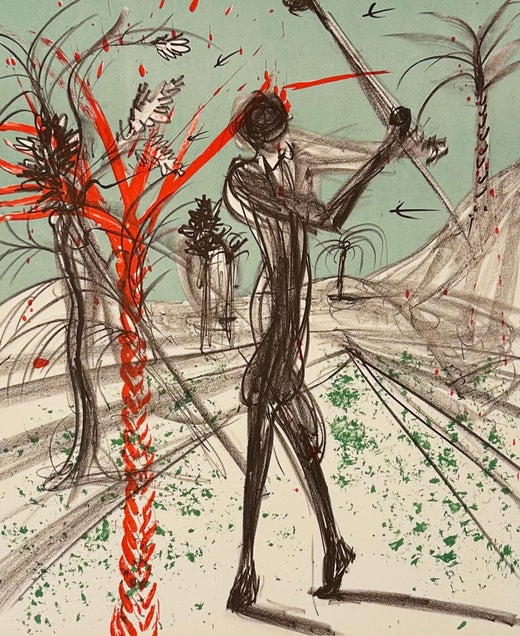

Abstract Surrealist Lithograph

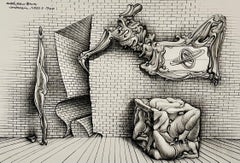

Souterrain No. 13 8 1944 Musée Jean Brun

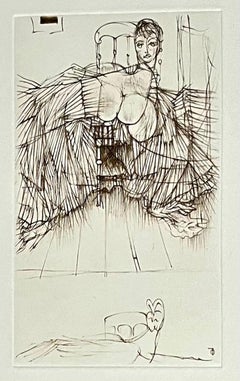

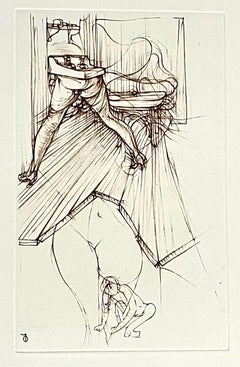

Date: circa 1965

Hand signed and numbered in pencil Edition of 100

Size: 19.5 x 26.5 in.

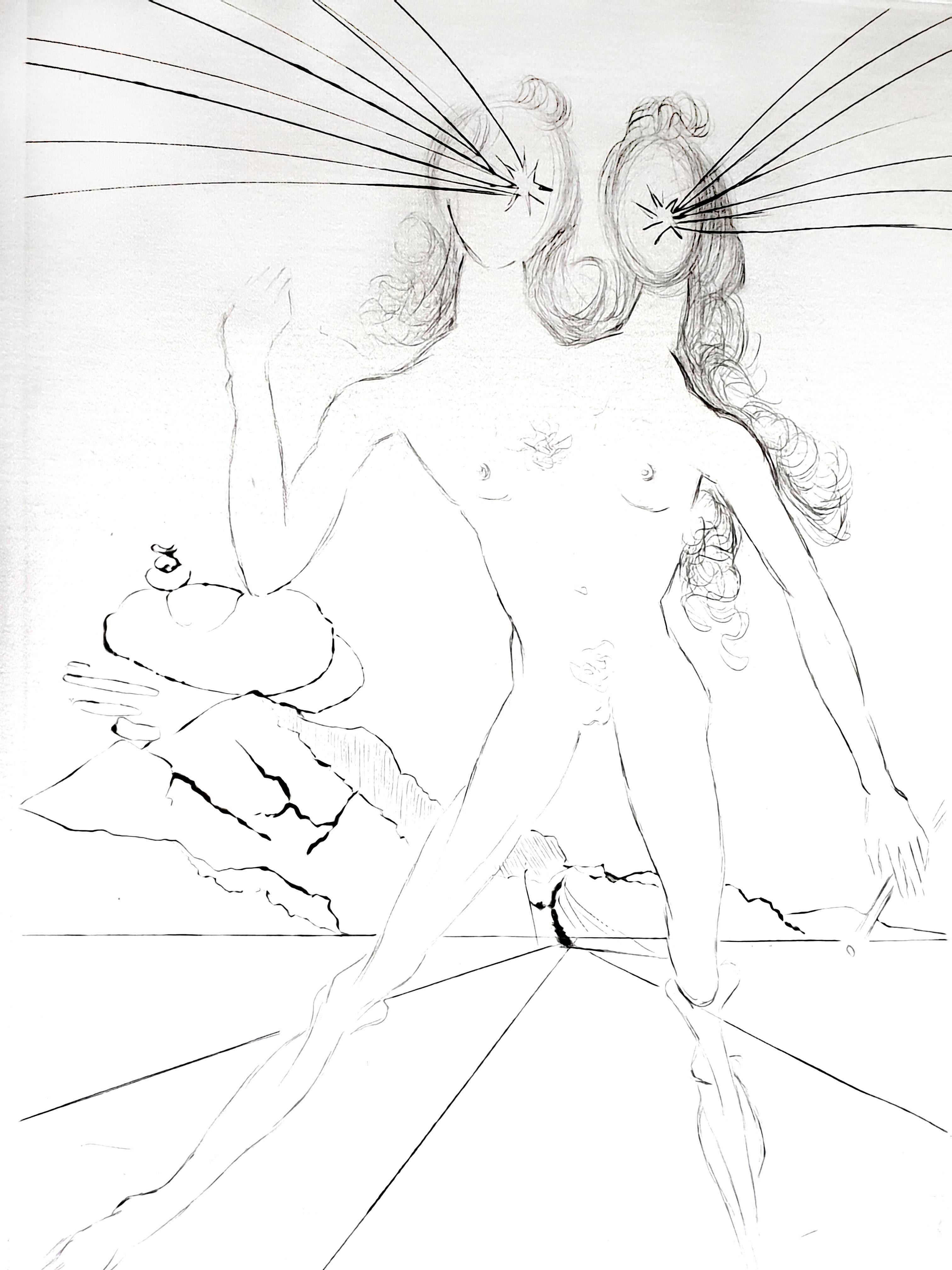

Hans Bellmer ( 1902 – 1975) was a Polish born German artist, best known for his drawings, etchings that illustrates the 1940 edition of Histoire de l’œil, and the life-sized female sculpture mannequin dolls he produced in the mid-1930s. Historians of art and photography also consider him a Surrealist photographer.

Bellmer was born in the city of Kattowitz, then part of the German Empire (now Katowice, Poland). Up until 1926, he worked as a draftsman for his own advertising company.

Bellmer is most famous for the creation of a series of dolls as well as photographs of them. He was influenced in his choice of art form in part by reading the published letters of Oskar Kokoschka (Der Fetisch, 1925) and Surrealism. Bellmer's puppet doll project is also said to have been catalysed by a series of events in his personal life.

Hans Bellmer takes credit for provoking a physical crisis in his father and brings his own artistic creativity into association with childhood insubordination and resentment toward a severe and humorless paternal authority. Perhaps this is one reason for the nearly universal, unquestioning acceptance in the literature of Bellmer's promotion of his art as a struggle against his father, the police, and ultimately, fascism and the state. Events of his personal life also including meeting a beautiful teenage cousin in 1932 (and perhaps other unattainable beauties), attending a performance of Jacques Offenbach's Tales of Hoffmann (in which a man falls tragically in love with an automaton), and receiving a box of his old toys. After these events, he began to actually construct his first dolls. In his works, Bellmer explicitly sexualized the doll as a young girl (his work bears connection to the works of Bathus). Hirschfeld has claimed (without further argumentation) that Bellmer initiated his doll project to oppose the fascism of the Nazi Party by declaring that he would make no work that would support the new German state. Represented by mutated forms and unconventional poses, his dolls (according to this view) were directed specifically at the cult of the perfect body then prominent in Germany.

He visited Paris in 1935 and made contacts there, such as Paul Éluard, but returned to Berlin because his wife Margarete was dying of tuberculosis. He was part of the circle of Surrealist luminaries such as Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Joan Miro, André Masson, René Magritte, Alberto Giacometti and Salvador Dali as well as women artists—such as Frida Kahlo, Dorothea Tanning and Leonora Carrington.

Bellmer produced the first doll in Berlin in 1933. Long since lost, the assemblage can nevertheless be correctly described thanks to approximately two dozen photographs Bellmer took at the time of its construction. Standing about fifty-six inches tall, the doll consisted of a modeled torso made of flax fiber, glue, and plaster; a mask-like head of the same material with glass eyes and a long, unkempt wig; and a pair of legs made from broomsticks or dowel rods. One of these legs terminated in a wooden, club-like foot; the other was encased in a more naturalistic plaster shell, jointed at the knee and ankle. As the project progressed, Bellmer made a second set of hollow plaster legs, with wooden ball joints for the doll's hips and knees. There were no arms to the first sculpture, but Bellmer did fashion or find a single wooden hand, which appears among the assortment of doll parts the artist documented in an untitled photograph of 1934, as well as in several photographs of later work.

Bellmer's 1934 anonymous book, The Doll (Die Puppe), produced and published privately in Germany, contains 10 black-and-white photographs of Bellmer's first doll arranged in a series of "tableaux vivants" (living pictures). The book was not credited to him, as he worked in isolation, and his photographs remained almost unknown in Germany. Yet Bellmer's work was eventually declared "degenerate" (entartete kunst) by the Nazi Party, and he was forced to flee Germany to France in 1938, where Bellmer's work was welcomed by the Surrealists around Andre Breton.

He aided the French Resistance during the war by making fake passports. He was imprisoned in the Camp des Milles prison at Aix-en-Provence, a brickworks camp for German nationals, from September 1939 until the end of the Phoney War in May 1940.

After the war, Bellmer lived the rest of his life in Paris. Bellmer gave up doll-making and spent the following decades creating erotic drawings, etchings, sexually explicit photographs, paintings, and prints of pubescent girls. In 1954, he met Unica Zürn, who became his companion until her suicide in 1970. He continued working into the 1960s

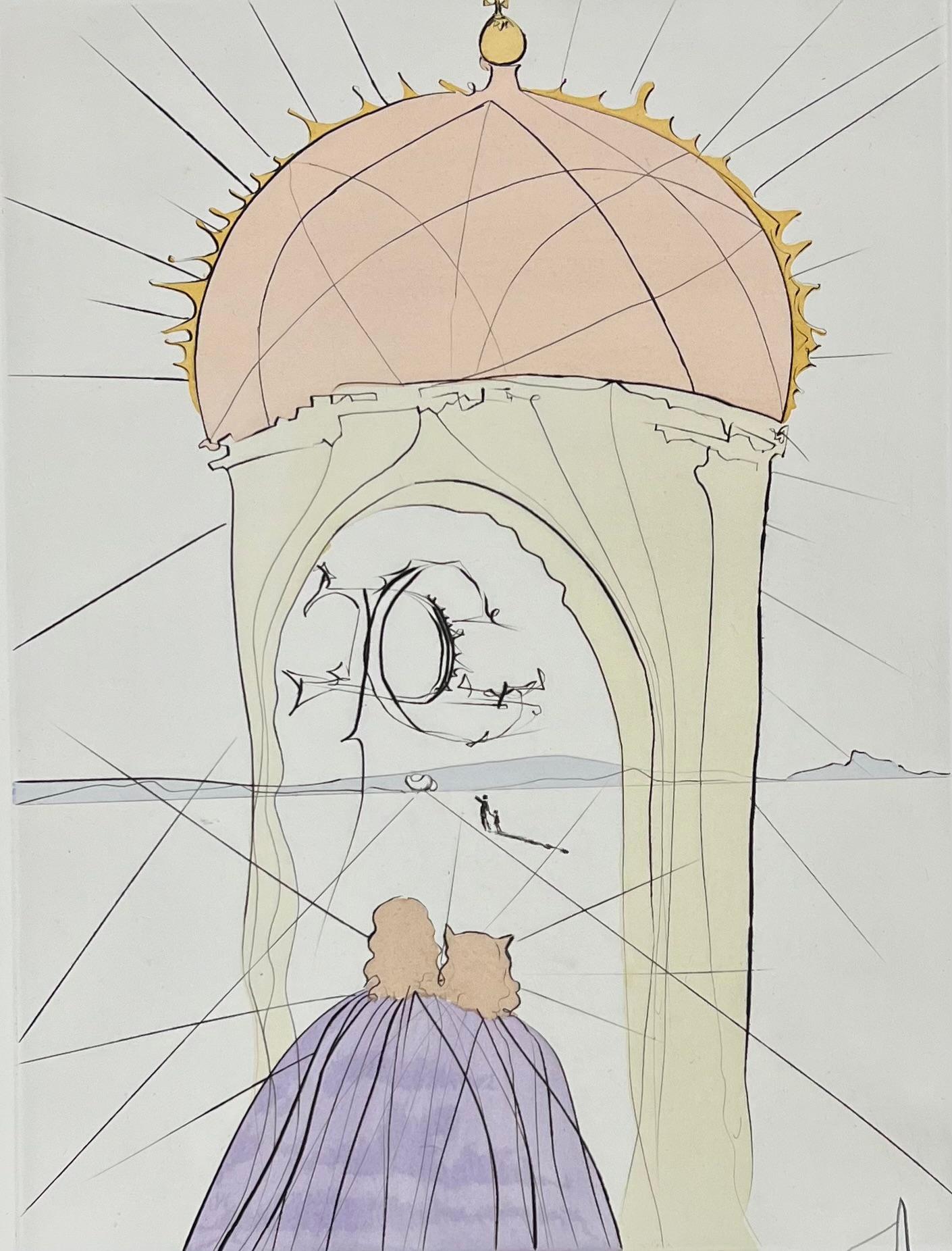

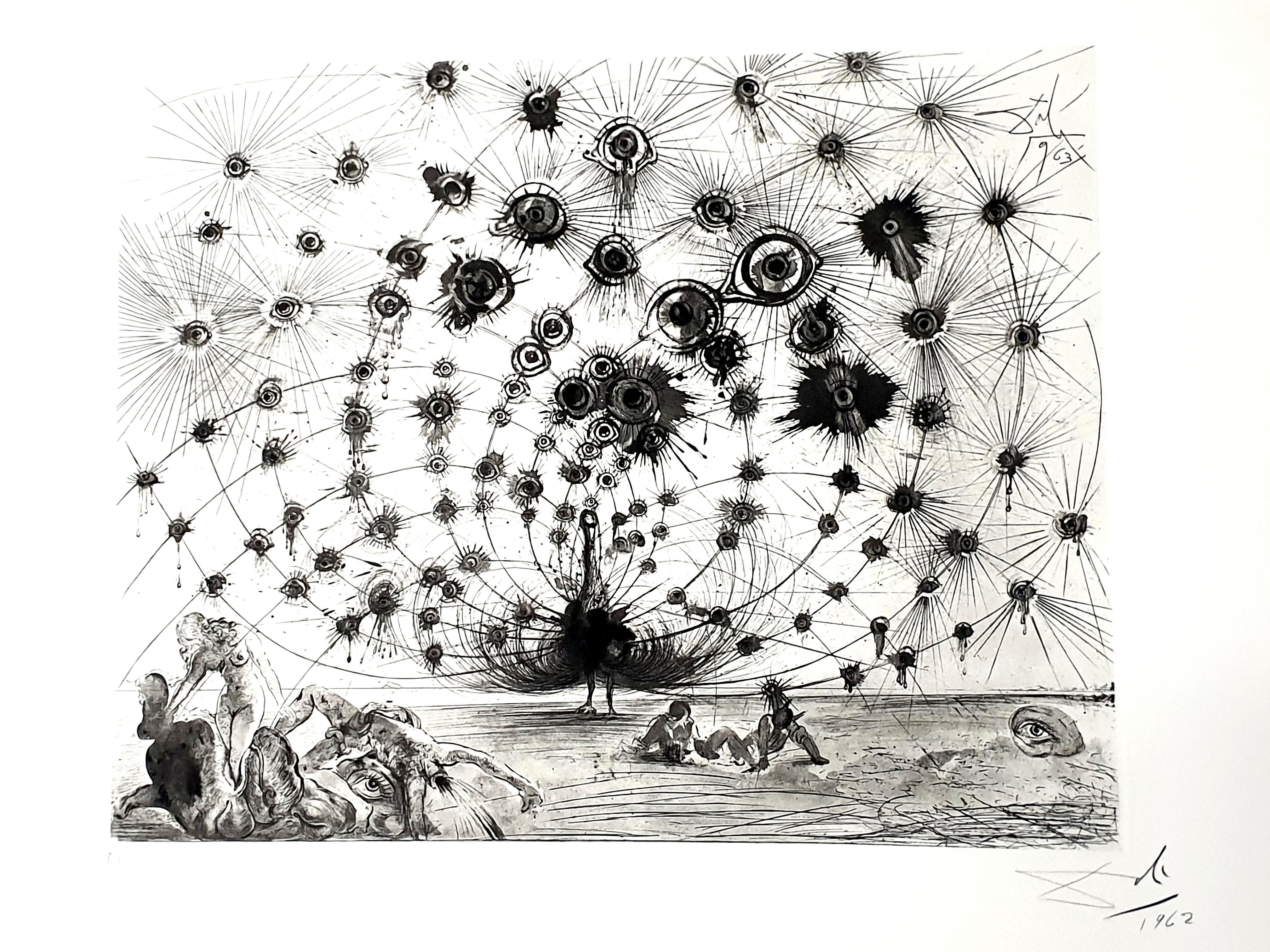

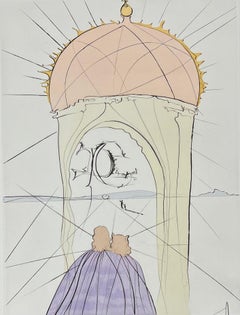

Cécile Reims (1927) has been drawing the world that surrounds her since her childhood in Lithuania, and subsequently in Paris, Jerusalem, and Barcelona. As a Jew, she had to go into hiding during World War II, and found herself at death’s door when she contracted tubercu- losis. Recovering from the disease, she felt she had to give meaning to her life as a survivor and she experienced a “conversion to art” as one is converted to a religion. Her encounter with the engraver Joseph Hecht in 1945 introduced her to the burin, an unforgiving tool which became her medium of choice. In her early years as an artist, she produced the mysterious Visages d’Espagne, Metamorphoses and Bestiaire de la mort series. But in order to support her work as an artist and to help Fred Deux (1924), whom she married in 1952, she suddenly gave a new twist to her career by turning to the interpretation of others’ work and engraving the drawings made by other artists. Cécile Reims filled this role with good humour and immense talent, as well as secretly collaborating with numerous artists working in the surrealist mode, such as Hans Bellmer, from 1966 to 1975, Salvador Dalí, from 1969 to 1988, Fred Deux, from 1970 to 2008, and Leonor Fini, from 1972 to 1995.

In 2004, the Bibiothèque Nationale de France held an important retrospective devoted to Cécile Reims, suddenly putting into the limelight a figure who had long been kept in the shadows. At that point it became essential to produce a catalogue raisonné of her

miniature engravings...